eBook - ePub

Racial Stereotyping and Child Development

- 132 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Racial Stereotyping and Child Development

About this book

In contemporary societies children's racial identity is co-constructed in response to racial stereotyping with extended family, peers and teachers, and potent media sources. The studies in this volume take cognizance of earlier research into skin color and racial stereotyping, but advance its contemporary implications. Developmental trajectories of racial attitudes of Black and White children, examining recent empirical research from the perspective of theorizing associated with experimental studies of stereotyped-threat are discussed. Reviewed are also the theoretical and empirical role of media images in influencing the race-related images as well as the PVEST theoretical model in considering the significance of parental racial messages and stories. The last paper argues that youth can be victimized by racial/cultural stereotyping despite being majority-Black cultural members. Interdisciplinary commentaries by scholar-researchers are given for each chapter. Researchers, academicians, and practitioners will find in this publication a succinct update, inclusive of references and bibliographies, regarding the latest information in the development and socialization of racial attitudes and racial stereotyping.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Racial Stereotyping and Child Development by D. T. Slaughter-Defoe,D.T., Slaughter-Defoe, L. Nucci,L., Nucci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Nursing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Paper

Slaughter- Defoe DT (ed): Racial Stereotyping and Child Development.

Contrib Hum Dev. Basel, Karger, 2012, vol 25, pp 57-79

Contrib Hum Dev. Basel, Karger, 2012, vol 25, pp 57-79

______________________

‘What Does Race Have to Do with Math?’ Relationships between Racial-Mathematical Socialization, Mathematical Identity, and Racial Identity

Traci L. English-Clarkea · Diana T. Slaughter-Defoea · Danny B. Martinb

aUniversity of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa., and bUniversity of Illinois, Chicago, III., USA

Author note: This chapter stems from the first author's dissertation research, which focused on mathematical, racial, and racial-mathematical socialization messages and stories and their role in shaping African-American youths’ mathematical identities. In the dissertation, mixed methods were used to explore the relationships between racial and mathematical socialization and identity by analyzing surveys of 263 youth of various races (168 African-American) in 9th and 10th grades and in-depth, one-on-one interviews with 28 African-American youth. English-Clarke examined the mathematical, racial, and racial-mathematical socialization received by African-American youth, as well as the ways in which the youth perceived and used this socialization.

______________________

Abstract

In this chapter, we focus on the racial-mathematical socialization stories and messages reported by African-American youth and the significance of these stories and messages in terms of youths’ mathematical identities. We also examine the relationship between racial-mathematical beliefs and youths’ mathematical and racial identities. In examining youths’ negotiation of racial-mathematical stereotypes, we found that racial identity constructs were more closely related to racial-mathematical beliefs for 10th graders than for 9th graders. This suggests that as youths’ racial identities develop, their understandings about race increasingly affect their racial-mathematical beliefs. Additionally, about one-third of the interviewed youth reported hearing racial-mathematical messages or stories from parents or other people. The majority of these stories and messages described racial discrimination in a mathematical setting, while others touched on racial-mathematical stereotypes or the dearth of African-Americans in high-level mathematics. Racial-mathematical socialization may serve as a special support for youth rather than just an additional context for racial socialization; youth who hear racial-mathematical socialization stories or messages may develop a deeper and more complex understanding of the far-reaching effects of discrimination, the youth-relevant contexts in which discrimination can occur, and the racial imbalances that they may perceive and experience as they reach higher levels of mathematics.

Copyright © 2012 S. Karger AG, Basel

One's personal identity has been theorized to develop over time and in response to one's experiences, including environment-based risks, protective factors, situation-based challenges, and supports that protect against these challenges Spencer, [1995]. Socialization messages, including racial socialization, can serve as a challenge or support for youth, depending on the content of the socialization messages and the ways in which the youth perceive them. Mathematical identity for African-American youth is likely similar to personal identity in that it develops over time and in response to an individual's experiences [Berry, 2008; Jackson, 2009; McGee, 2009; Martin, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2009; McGee & Martin, 2011; Spencer, 2009; Stinson, 2006, 2009, 2011]. However, for African-Americans, the experiences influencing mathematical identity not only include classroom-based and out-of-school mathematical experiences, but also socialization stories or messages from parents and the larger society involving both race and mathematics. For example, some African-American adults and parents feel a need to help African-American children overcome negative thinking that mathematics is for others and that mathematics participation is determined by race [Martin, 2000, 2006, 2007].

This chapter will examine the linkages between race and mathematics from the perspectives of African-American youth. First, we explore racial-mathematical socialization stories and messages reported by African-American youth and the significance of these stories and messages in terms of youths’ mathematical identities. We then investigate youths’ racial-mathematical beliefs (primarily racial stereotypes about math). We also examine the relationship between racial-mathematical beliefs and youths’ mathematical and racial identities.

Background

Theoretical Framework

Educational research and interventions based on models of psychosocial and cognitive development that take for granted European and European American, middle-class norms may not be relevant to the lives of youth from other cultures, and thus may not bring about the researchers’ desired understanding [Gordon, 1990; Lee, Spencer & Harpalani, 2003; Tillman, 2002]. For many years, theorists tended to view youths’ motivation to achieve in school as largely irrelevant of social, cultural, and environmental context – neither social position variables nor experiences of racism and segregation are explicitly examined in these models [i.e., Dweck, 1999; Eccles, 1997; Nicholls, 1984; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000]. Mathematics education researchers as well as those examining Black-White achievement differences also tended to ignore the social conditions and realities of those populations they were studying, or viewed negative outcomes for African-Americans as a result of cultural deficits [Slaughter-Defoe, 1995]. However, there has been a push in recent years to investigate the social contexts in which individuals live – including issues around social class, race/ethnicity, culture, language, gender, sexuality, and more – and to include their daily life experiences as a factor in their life processes and outcomes [Nasir & Saxe, 2003; Oyserman, Gant & Ager, 1995; Spencer, 1995; Spencer et al., 2006].

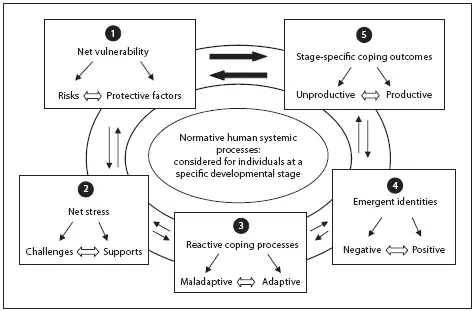

Spencer's Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST) helps to elucidate some of these contextual components and variables and the ways in which they might interact with daily experiences to form a youth's identity over time [Spencer, 1995]. PVEST (fig. 1) is a framework that is designed to help us understand the normative development of people belonging to different racial and ethnic groups, social classes, and genders.

It invites us to look closely at the individual risks and protective factors in an individual's or group's environment, along with the challenges one faces and the supports that protect against these challenges. The framework includes the coping strategies that individuals use to deal with their net stress level (challenges and supports combined), allowing us to categorize the strategies as adaptive or maladaptive according to the immediate outcomes in a given context. The framework also includes the emergent identities, the positive and negative stable coping responses that are developed when the coping strategies are used over time, and the coping outcomes (productive or unproductive) that result. This is a recursive model, in that outcomes at one point in time can become risk or protective factors, or even challenges or supports, later on in the individual's experience.

Fig. 1. Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST). [Spencer et al. 2006, p. 641], reprinted with permission.

This framework is helpful in that it allows us to dig deeper into the meanings that African-American adolescents construct, as well as the behaviors that they exhibit, towards math in school based on their experiences and socialization around race and mathematics. Youth are not empty vessels when they arrive at school each day – they experience socialization around race and mathematics that influences how they respond to mathematics in their classrooms. Learning about this socialization and the ways in which African-American youth negotiate the messages that they receive – be they explicit or implicit, verbal or nonverbal – will allow us to better understand their coping strategies and the processes that lead to youths’ racial and mathematical identities.

Next, we briefly discuss identity development for youth, especially as it pertains to their racial identity development. As African-American youths’ identities around mathematics may be related to their identities around race [Berry, 2008; Martin, 2000], we must examine theories about adolescent identity in general and racial identity in particular before we can begin to understand mathematical identity for this group of youth.

Identity Development

During adolescence, youth begin to question various aspects of their identities such as belief systems, social structures, personal values, and roles. For the purposes of this chapter, we use a definition of identity in the Eriksonian tradition, ‘an ongoing dynamic process whereby individuals establish, evaluate, reevaluate, and reestablish who they are and are not relative to others in their environments’ [Chatman, Eccles & Malanchuk, 2005, p. 117]. Erik Erikson's theory of identity development states that adolescents experience an identity crisis that is most pronounced during this life stage. This identity crisis is never fully resolved, as identity issues are frequently reevaluated in the face of major life changes. During this initial identity crisis, however, the adolescent is faced with the task of establishing ‘a sense of personal identity’ and avoiding the dangers of ‘role diffusion’ and ‘identity confusion’, which could lead to self-destructive behaviors. The adolescent must resolve issues regarding who she/he is, where she/ he came from, and who she/he wants to become. In other words, identity construction involves establishing a meaningful self-concept that brings together one's past, present, and future. When adolescents begin to construct and negotiate their identities, they tend to seek feedback from older generations, peers, and others, as the various aspects of identity can only be found through interaction with significant others. During this process, there is a preoccupation with how one appears in the eyes of others, in order to compare this perception to how one feels and strives to be. Eventually, the adolescent achieves a mature identity, which gives her/him a sense of knowing where she/he is headed and a self-assurance that she/he will receive recognition from those who matter the most [Muuss, 1996].

Building on Erikson's theory, James Marcia further hypothesized that adolescents’ identity development consists of four non-hierarchical phases: identity-diffused, foreclosure, moratorium, and identity-achieved. The identity-diffused youth has not yet had an identity crisis and has not explored various roles or beliefs, nor has she/he personally committed to particular goals, values, or beliefs. The youth in the status of foreclosure has not yet had an identity crisis, but she/he has made a commitment to certain goals, values, and beliefs based solely on socialization by parents or significant others. The moratorium status is one in which the adolescent is in a state of exploration, and thus tries on many different roles or values in search of the ones that suit her or him, but has not yet made a permanent commitment to any in particular. The identity-achieved status is one of completion, in which the youth has resolved his or her identity issues through exploration. She/he has made a well-defined personal commitment to particular beliefs, roles, and values. Being in a certain identity status can have implications for one's self-concept, level of anxiety, and other aspects of emotional experience [Muuss, 1996].

Racial Identity Development

The exploration of one's racial identity may not be an important issue for majority-race adolescents, as it is not necessarily a salient aspect of their personal identity [Phinney & Alipuria, 1990; Rotheram-Borus, 1989, as cited in Muuss, 1996]. However, together with general identity search issues, adolescents who are members of racial minority groups may also begin to actively search for racial identities [Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990]. For African-Americans, ‘Blackness’ is said to perform three functions in everyday African-American life: defending the individual from the negative psychological stress of living in a racist society; providing a sense of purpose, affiliation and meaning, and providing psychological mechanisms that facilitate social interaction with non-African American people, situations and cultures [Cross, 1991]. It is likely that other racial identities perform similar functions (specific to the group) which seem essential for life in a society where many individuals have different racial and cultural experiences from one's own.

Most researchers hold the theoretical perspective that the process of racial identity development is similar to that of Erikson and Marcia's model for other aspects of identity development, in that there are four general phases: (1) Initially, youth have the attitudes of those around them, and (2) at some point they encounter a situation or series of events that cause them to question their racial identity and the role of race in their world. They then go through two other phases during which they (3) try on other attitudes and challenge those around them, and (4) finally settle on an identity that works for them [Bennett, 2006; Phinney & Chavira, 1995; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Seaton, Scottham & Sellers, 2006].

Research on ethnic and racial identity development suggests that African-American youth, as well as other minority youth, may have many identity tasks to accomplish during adolescence that reach far beyond the identity tasks of Caucasian American youth. Researchers such as Helms [2007] have developed theories that detail the racial identity development of Whites, but they suggest that White racial identity development often occurs at a much later age than for minority youth [Tatum, 1997]. Exploring one's racial identity is simply more salient for African-Americans than for White youth, although members of both races may have begun to think about and search for a racial identity by the 8th grade [Rotheram-Borus, 1989, as cited in Muuss, 1996]. The main reason for this greater salience is that African-American youth and other minority youth realize at a young age that they are seen as members of a group rather than as individuals [Tatum, 1997]. They realize that they are not like those around them – in fact, that they are living in a society in which most of the people portrayed in the media, government, positions of power, and people who are considered to embody universal standards of beauty do not look or sound anything like them. Additionally, these youth usually face discrimination and racism in their daily lives, or at the very least, they hear about racism from their parents and other adults around them. Caucasian youth growing up in mostly White neighborhoods tend to consider themselves to be racially ‘normal’ – they see race largely as belonging to minorities [Tatum, 1997]. They typically do not experience racism and thus do not tend to think about their race as a major factor in their identities.

Content of a Racial Identity

Phinney and Ong [2007] reviewed several components of racial and ethnic identity content that have been explored with adolescent populations: self-categorization and labeling, commitment and attachment, exploration, behavioral involvement, in-group attitudes or private regard, ethnic values and beliefs, importance or salience of group membership, and ethnic identity in relation to national identity. Self-categorization is simply identifying oneself as a member of a particular social group, and is a basic element of ethnic/ racial identity. Commitment refers to one's attachment to and personal investment in a group. These researchers suggest that commitment is the most important aspect of racial/ethnic identity. Commitment is one major aspect of Marcia's expansion of Erikson's theory for adolescent identity [Muuss, 1996]; along with exploration, it determines an individual's location in the phases of the status model. Exploration is the search for experiences and information that are relevant to one's developing identity. Without exploration, one's commitment to a particular i...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Material

- Through the Eyes of a Child: the Development and Consequences of Racial Stereotypes in Black and White Children

- Should Stereotype Consciousness Be Taught to Children? A Discussion Informed by Bogan and Slaughter-Defoe’s Through the Eyes of a Child.

- What's Not in the Box?: Historical and Population Change as Contextual Features in the Study of Race- Based Development of Children

- Media Socialization, Black Media Images and Black Adolescent Identity

- Adolescents, Race, and Media.

- Damned if You Do and Damned If You Don't! What are the Correct Media Images for Black People in the Media and How Can We Know?

- Social Media, Privacy and Identity

- ‘What Does Race Have to Do with Math?’ Relationships between Racial-Mathematical Socialization, Mathematical Identity, and Racial Identity

- ‘What Do Race and Math Have to Do with Each Other?’ Relationships between Racial-Mathematical Socialization, Mathematical Identity, and Racial Identity

- The Need to Incorporate Observations of Implicit Socialization in the Contexts of Everyday Life

- ‘What Does Race Have to Do with Math?’ Relationships between Racial-Mathematical Socialization, Mathematical Identity, and Racial Identity

- On Researching the Agency of Africa's Young Citizens: Issues, Challenges and Prospects for Identity Development

- On Researching the Agency of Youth: Moving Beyond Traditional Theorizing.

- Advancing an African Research Agenda for Child Development.

- Epilogue

- Author Index

- Subject Index