eBook - ePub

The Importance of Immunonutrition

77th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Panama, October-November 2012

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Importance of Immunonutrition

77th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Panama, October-November 2012

About this book

Our daily food intake not only provides the calories and the macro- and micronutrients necessary for survival - nutrients also have a tremendous potential to modulate the actions of the immune system, a fact which has a significant impact on public health and clinical practice. This book presents the latest findings on how nutrient status can modulate immunity and improve health conditions in pediatric patients. Divided into three parts, it covers major aspects of the interplay between nutrients and the regulation of immunity and inflammatory processes. Part one deals with the pharmaceutical value of specific amino acids (arginine and glutamine) and hormones for addressing immune disorders and infant development. The second part revolves around gut function and immunity, and the right balance of probiotics. The final part explores the role of lipid mediators and how their types and proportions can tip the balance in favor of health and disease.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Importance of Immunonutrition by M. Makrides,J. B. Ochoa,H. Szajewska,M., Makrides,J.B., Ochoa,H., Szajewska, M. Makrides, J. B. Ochoa, H. Szajewska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Immunology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Modulation of Immune Responses and Nutrition

Makrides M, Ochoa JB, Szajewska H (eds): The Importance of Immunonutrition.

Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, vol 77, pp 1-15, (DOI: 10.1159/000351365)

Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG., Basel, © 2013

Nestlé Nutr Inst Workshop Ser, vol 77, pp 1-15, (DOI: 10.1159/000351365)

Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG., Basel, © 2013

______________________

Arginine and Asthma

Claudia R. Morris

Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Emory-Children's Center for Developmental Lung Biology, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA

______________________

Abstract

Recent studies suggest that alterations of the arginine metabolome and a dysregulation of nitric oxide (NO) homeostasis play a role in the pathogenesis of asthma. L-Arginine, a semi-essential amino acid, is a common substrate for both the arginases and NO synthase (NOS) enzyme families. NO is an important vasodilator of the bronchial circulation, with both bronchodilatory and anti-inflammatory properties, and is synthesized from oxidation of its obligate substrate L-arginine, which is catalyzed by a family of NOS enzymes. Arginase is an essential enzyme in the urea cycle, responsible for the conversion of arginine to ornithine and urea. The NOS and arginase enzymes can be expressed simultaneously under a wide variety of inflammatory conditions, resulting in competition for their common substrate. Although much attention has been directed towards measurements of exhaled NO in asthma, accumulating data show that low bioavailability of L-arginine also contributes to inflammation, hyperresponsiveness and remodeling of the asthmatic airway. Aberrant arginine catabolism represents a novel asthma paradigm that involves excess arginase activity, elevated levels of asymmetric dimethyl arginine, altered intracellular arginine transport, and NOS dysfunction. Addressing the alterations in arginine metabolism may result in new strategies for treatment of asthma.

Copyright © 2013 Nestec Ltd., Vevey/S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

Asthma is a common pulmonary condition that involves heightened bronchial hyperresponsiveness and reversible bronchoconstriction together with acute-on-chronic inflammation that leads to airway remodeling [1]. Over 22 million people in the United States have asthma including more than 6.5 million chil-dren, and as many as 250 million worldwide are affected. Mechanisms that contributed to asthma are complex and multi-factorial, influenced by genetic polymorphisms as well as environmental and infectious triggers. In susceptible individuals, this inflammation causes recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread but variable airflow obstruction that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment. The inflammation also causes an associated increase in the existing bronchial hyperresponsiveness to a variety of stimuli [2].

‘Asthma’ is a clinical diagnosis based on a constellation of symptoms described above, yet asthma is not one disease. Different patients have biochemically distinct phenotypes despite a similar clinical manifestation [3]. Examples include decreased activity of superoxide dismutases, increased activity of eosinophil peroxidase, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase, decreased airway pH, and finally alterations of the arginine metabolome. Low plasma arginine concentration together with increased activity of the arginase enzymes, elevated levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), altered intracellular arginine transport, and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) dysfunction, including endogenous NOS inhibitors and uncoupled NOS can contribute to arginine dysregulation in asthma and is the focus of this discussion.

Asthma: Global Disruption of the Arginine-Nitric Oxide Pathway

Altered Nitric Oxide Homeostasis

Nitric oxide (NO) has been well described in the literature as an important signaling molecule involved in the regulation of many mammalian physiologic and pathophysiologic processes, particularly in the lung [4]. NO plays a role in regulation of both pulmonary vascular tone as well as airway bronchomotor tone through effects on relaxation of smooth muscle. In addition, NO participates in inflammation and host defense against infection via alterations in vascular permeability, changes in epithelial barrier function and repair, cytotoxicity, upregulation of ciliary motility, altered mucus secretion, and inflammatory cell infiltration [5]. These multiple functions of NO have been implicated in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory airway diseases such as asthma.

NO is produced by a family of NOS enzymes that metabolize L-arginine through the intermediate N-hydroxy-L-arginine (NOHA) to form NO and L-citrulline using oxygen and NADPH as cosubstrates. Three NOS mammalian isoenzymes have been identified with varying distributions and production of NO. Neuronal (nNOS or NOS I) and endothelial (eNOS or NOS III) NOS are constitutively expressed (cNOS) in airway epithelium, inhibitory nonadrenergic noncholinergic (iNANC) neurons, and airway vasculature endothelial cells. Their activity is regulated by intracellular calcium, with rapid onset of activity and production of small amounts of NO on the order of picomolar concentrations. Inducible NOS (iNOS or NOS II) is transcriptionally regulated by proinflammatory stimuli, with the ability to produce large amounts (nanomolar concentrations) of NO over hours [5].

iNOS is known to be upregulated in asthmatic lungs, and increased levels of exhaled NO are well described in asthma patients. In both human and experimental animal models of asthma, increased NO production occurs in the airways related to upregulation of NOS II (iNOS) by proinflammatory cytokines after allergen challenge and during the late asthmatic reaction [4]. This upregulation of NOS II in airway epithelial cells and inflammatory cells is associated with airway eosinophilia, airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and increased NO in exhaled air [6]. Although initially assumed to contribute to asthma, the increased production of NO itself may not be responsible for AHR as NO also seems to have a protective effect on bronchial muscle tone. It is believed that the AHR after the late asthmatic reaction is caused by increased formation of peroxynitrite [7] that occurs due to reduced availability of L-arginine for NOS II, which potentially causes uncoupling of this enzyme [8]. Increased activity of the arginase enzyme, which competes with NOS for the substrate L-arginine seems to be, at least in part, responsible for this process [9].

Mechanisms of Arginine Dysregulation

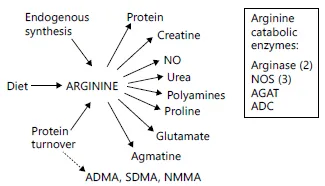

As the obligate substrate for NOS, L-arginine bioavailability plays a key role in determining NO production, and is dependent on pathways of biosynthesis, cellular uptake, and catabolism by several distinct enzymes (fig. 1), including those from the NOS and arginase enzyme families. Biosynthesis of the semi-essential amino acid occurs in a stepwise fashion in what is called the ‘intestinal-renal axis’. L-Glutamine and L-proline are absorbed from the small intestine and converted to L-ornithine. L-Citrulline is then synthesized from L-ornithine by ornithine carbamoyltransferase and carbamoylphosphate synthetase 1 in hepatocytes as part of the urea cycle, as well as in the intestine. L-Arginine is produced from L-citrulline by cytosolic enzymes argininosuccinate synthetase 1 and argininosuccinate lyase. When L-arginine is subsequently metabolized to NO via NOS, L-citrulline is again produced and can be used for recycling back to L-ar-ginine, which may be an important source of L-arginine during prolonged NO synthesis by iNOS [10]. Low arginine bioavailability develops abruptly during acute asthma exacerbations and normalizes with clinical recovery [11]. In severe asthma, however, low arginine bioavailability at baseline is strongly associated with airflow abnormalities [12]. Overlapping mechanism that contribute to arginine depletion in asthma are summarized below.

Fig. 1. Sources and metabolic fates of L-arginine. Arginine is produced through de novo synthesis from citrulline primarily in the proximal tubules of the kidney, through protein turnover or via uptake from the diet. Four enzymes use arginine as their substrate: the NOS, arginases, arginine decarboxylase (ADC) and arginine:glycine amidinotransferase (AGAT). The action of these 4 sets of enzymes ultimately results in production of the 7 products depicted in the figure. Putrescine, spermine and spermidine are the polyamines produced as downsteam byproducts of arginase activity. Turnover of proteins containing methylated arginine residues releases ADMA, SDMA and N-methylarginine (NMMA) which are potent inhibitors of NOS. Reproduced with permission from Morris [10].

Increased Arginase Concentration and Activity

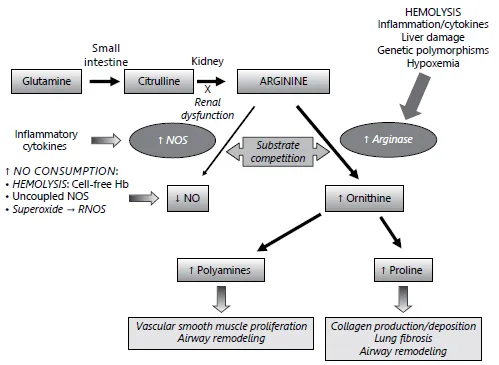

Arginase is an essential enzyme in the urea cycle, responsible for the conversion of arginine to ornithine and urea. The NOS and arginase enzymes can be expressed simultaneously under a wide variety of inflammatory conditions, resulting in competition for their common substrate [9]. Two forms of arginase have been identified, type 1, a cytosolic enzyme highly expressed in the liver, and type 2, a mitochondrial enzyme found predominantly in the kidney, prostate, testis, and small intestine [13]. Both forms are expressed in human airways. Arginase-1 is also present in human red blood cells, which has significant implications for hemolytic disorders. Of particular interest is the high prevalence of asthma in sickle cell disease [14], a hemolytic anemia also associated with an altered arginine metabolome (fig. 2) [15, 16].

Fig. 2. Altered arginine metabolism in hemolysis. A path to pulmonary dysfunction. Dietary glutamine serves as a precursor for the de novo production of arginine through the citrulline-arginine pathway. Arginine is synthesized endogenously from citrulline primarily via the intestinal-renal axis. Arginase and NOS compete for arginine, their common substrate. In sickle cell disease (SCD) and thalassemia, bioavailability of arginine and NO are decreased by several mechanisms linked to hemolysis. The release of erythrocyte arginase during hemolysis increases plasma arginase levels...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Modulation of Immune Responses and Nutrition

- Microbiota and Pro-/Prebiotics

- Lipids

- Concluding Remarks

- Subject Index