eBook - ePub

Neonatal Pharmacology and Nutrition Update

- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neonatal Pharmacology and Nutrition Update

About this book

In order to provide safe and effective drug therapy to neonates, it is necessary to know about and understand the impact their development has on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs. The fact that children are different and neonates very different from adults means that, in neonates, it would be unwise to dose medications by scaling down adult doses proportionately, simply attempting to match their smaller weight and/or body surface area. When one makes decisions about neonatal drug therapy, one must not only take into consideration the available data but also critically assess and interpret this information within the context of fetal development and maturational processes as well as within the context of diseases that might affect a drug's biodisposition. This book includes the latest information on the regulation and scientific basis of drug development and also provides a rationale for formula development for preterm infants. It offers guidance on how to translate pharmacokinetic data into dosing recommendations and also covers legal and regulatory issues relating to neonatal pharmacotherapy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neonatal Pharmacology and Nutrition Update by F. B. Mimouni,J. N. van den Anker,F.B., Mimouni,J.N., van den Anker, Wieland Kiess,Wieland, Kiess in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Nutrition, Dietics & Bariatrics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Mimouni FB, van den Anker JN (eds): Neonatal Pharmacology and Nutrition Update.

Pediatr Adolesc Med. Basel, Karger, 2015, vol 18, pp 83-107 (DOI: 10.1159/000365032)

Pediatr Adolesc Med. Basel, Karger, 2015, vol 18, pp 83-107 (DOI: 10.1159/000365032)

______________________

Formulation of Preterm Formula: What's in it, and Why?

Francis B. Mimounia, b · Dror Mandelb, c · Ronit Lubetzkyb, c

aDepartment of Neonatology, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Jerusalem, bDepartment of Pediatrics, The Tel Aviv Medical Center, Tel Aviv, cSackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

______________________

Abstract

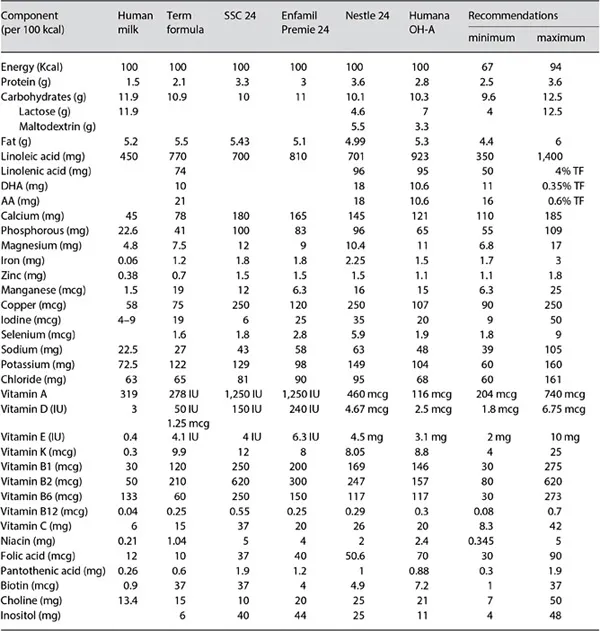

Human milk feeding of preterm infants reduces mortalityand morbidity (in particular sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis). When their own mother's milk is not available, and in the absence of donor milk, such fragile infants must be fed formula. In many instances, preterm infant formulas (PIFs) attempt to mimic the composition of human milk (the gold standard of infant feeding), but they must take into account as well the unique nutritional needs of the growing preterm infant, which are not identical to those of the healthy term infant. In this article we review the major characteristics of PIFs and try to evaluate the evidence and rationale behind their composition. At able comparing PIFs from several major manufacturers is presented for the convenience of the reader.

© 2015 S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) reaffirmed its recommendation that all preterm infants should receive their mother's own milk, fresh or frozen, as their primary diet, with the provision that it should be fortified appropriately for infants born weighing less than 1.5 kg [1]. In case the mother's own milk is unavailable despite significant lactation support, the AAP advised that pasteurized donor milk should be used [1]. In the AAP position statement, the arguments in support of human milk (HM) feeding include the significant short- and long-term beneficial effects of feeding preterm infants HM, such as: lower rates of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), lower mortality rates, fewer hospital readmissions for illness in the year after NICU discharge, and lower rates of long-term growth failure and neuro-developmental disabilities [1]. In spite of this statement, the use of a formula designed for premature infants might remain the only option when maternal milk is unavailable in adequate amounts and when no donor milk is available. Obviously, while preterm infant formulas (PIFs) have been designed to meet the nutritional requirements of the premature infant, they cannot mimic many of the biological properties of HM. The purpose of this chapter is to review the evidence behind the composition of PIFs. We will focus on PIFs designed for the immediate postnatal (in-hospital) period and will only briefly address the issue of post-discharge formulas. A table comparing PIFs from several major manufacturers is presented for the convenience of the reader (table 1).

Table 1. Components of HM and various preterm formulas

Fluid Intake and Energy Content

The European Society for Paediatric Gastoenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) regards 135 ml/kg as the minimum fluid volume and 200 ml/kg as a reasonable upper limit of daily fluid intake [2]. The basis behind this recommendation is mostly an expert consensus, as ‘randomised controlled trials on enteral fluid intake of “healthy” preterm infants are lacking as are studies comparing different fluid volumes providing identical nutrient intakes’. Moreover, it is believed that relatively low fluid intakes are likely to minimize the risks of bronchopulmonary dysplasia and patent ductus arteriosus. These beliefs are supported by a systematic review of 5 randomized trials evaluating varying parenteral fluid intake in premature infants, which showed that while restricted water intake significantly increased postnatal weight loss, it significantly decreased the rates of patent ductus arteriosus and NEC, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, intracranial hemorrhage and death [3]. Some infants, however, may require higher volumes to meet water (or other nutrient) requirements (particularly if insensible water losses are very high because of skin immaturity or because of the use of radiant heaters).

A few studies have been conducted that compared the growth and metabolic responses in preterm infants fed formulas with different energy contents. Generally, daily intakes ranging between 100 and 140 kcal/kg provide satisfactory growth [4, 5] while some infants, such as small for gestational age infants, may require energy intakes greater than 140 kcal/kg/day in order to grow [4]. Thus, the ESPGHAN concluded that a ‘reasonable range of energy intake for healthy growing preterm infants with adequate protein intake is 110 to 135 kcal/kg/day’. In one trial, 148 extremely low-birth-weight infants with a gestational age of 23-31 weeks were evaluated for protein and energy intake in first 4 weeks of life and for the outcome at age 18 months [6]. The energy intake in the first week of life appeared to be particularly decisive for the developmental outcome, with a Mental Development Index (MDI) increased by 4.6 points for each 10 kcal/kg/day increase in energy intake (p = 0.0134) in first week of life. In contrast, energy intake during the following 3 weeks was not correlated with MDI [6].

Consequently, PIFs exist in various versions according to their energy content: they are mostly available at 24, 27, or even 30 kcal/oz (1 oz = 29.57 ml, i.e. approximately 30 ml). The reason why a specific energy concentration is used is essentially related to how much fluid restriction is needed for a given infant.

Protein

Protein Concentration

PIFs are designed to provide preterm infants with a higher protein intake than that provided by standard ‘term’ formulas. Indeed, it is widely accepted that healthy pre-mature babies have daily protein requirements of 3.5-4.0 g/kg. A recent meta-analysis of infants born at <2,500 gm (low birth weight, or LBW) included 5 studies with 114 infants with a daily protein intake of 3-4 g/kg versus <3 g/kg [7]. Weight gain and nitrogen accretion were higher in the 3-4 g/kg group. The mean daily weight difference between the 2 groups was 2.36 g/kg (95% CI 1.31-3.4 g/kg) in favor of the higher protein intake. Two similar studies published thereafter (one in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants (birth weight (BW) < 1,500 g)) [8] and one in infants with a BW <1,250 g [6] led to similar conclusions. In the previously mentioned trial of 148 extremely low-birth-weight infants (BW < 1,000 g) with a gestational age of 23-31 weeks, the MDI increased 8.21 points for each 1 g/kg/day increase in protein intake in the first week of life, but the MDI was no longer influenced by protein intake during the following 3 weeks of life [9].

Protein Type

The predominant protein in HM is whey, followed by casein (80:20 ratio at the initiation of lactation decreasing to 50:50 in late lactation) [10]. PIFs are designed to be whey-dominant (60:40 ratio, usually chosen as an ‘average between 80:20 and 50:50) [10]. In premature infants, whey protein is usually preferred because for the following reasons: (1) compared to casein, it is believed to promote more rapid gastric emptying, which is supported by one study [11], while in another study, we showed that gastric emptying of a casein-predominant formula was similar to that of a whey-dominant formula [12]; (2) whey is believed to be more easily digested because the whey fraction is composed of soluble proteins [10]. We must note, however, that bovine whey (with beta-lactoglobulin as its major protein) is not equivalent to human whey (with alpha-lactalbumin as its major protein), and it does not have identical amino acid composition. Subsequently, plasma concentrations of individual amino acids are different in HM-fed and PIF-fed preterm infants: infants fed HM have the lowest concentrations of methionine, phenylalanine, and tyrosine, even at daily intakes of 1.6 g/kg protein through HM compared to whey or casein-dominant formulas, which provide 2.25 or 4.50 g/kg protein [13, 14]. Additionally, PIFs are routinely supplemented with cysteine and taurine, two amino acids that are present in HM and are necessary to synthesize the antioxidant glutathione (cysteine), or for bile conjugation and brain development (taurine) [15, 16]; (3) Human whey contains important proteins that play a role in host defense, such as lactoferrin, lysozyme, and secretory IgA [17]. Once again, we note that there are only traces of these proteins in bovine milk.

In the past decade, a few PIFs have been developed based upon hydrolyzed protein. In one trial, 129 VLBW infants were randomized (without intention-to-treat analysis) to hydrolyzed protein or standard preterm formula [18]. Infants randomized to hydrolyzed protein reached full feeds in 10 days versus 12 days for those randomized to standard PIF (p = 0.0024) [18]. Thus, hydrolyzed protein formulas maybe associated with increased feeding tolerance.

Lipids

Background

It would be extraordinarily difficult to use HM lipid composition as a model for formula lipid composition. Indeed, fats are the most variable constituents in HM, and they vary in composition over the course of a feeding (hindmilk is richer in fat than foremilk), from breast to breast, over a day's time (it is highly dependent upon maternal dietary fat intake and undergoes circadian variations), over time itself (total lipids range from approximately 2 g/dl on...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Influence of Maturation and Growth on Drug Metabolism from Fetal to Neonatal to Adult Life

- How to Translate Pharmacokinetic Data into Dosing Recommendations

- Pharmacovigilance in Neonatal Intensive Care

- Neonatal Formulations and Additives

- Modelling and Simulation to Support Neonatal Clinical Trials

- A Systematic Review of Paracetamol and Closure of Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Ready for Prime Time?

- Formulation of Preterm Formula: What's in it, and Why?

- Neonatal Pharmacotherapy: Legal and Regulatory Issues

- Author Index

- Subject Index