eBook - ePub

Technological Advances in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Technological Advances in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

About this book

The current epidemic of diabetes, obesity and related disorders is a driving force in the development of new technologies. Technological advances offer great new opportunities for the treatment of these chronic diseases. This review presents an update of developments that promise to revolutionize the treatment of diabetes. It examines hospital and outpatient care, intensive insulin therapy, blood glucose monitoring and innovative steps towards the construction of an artificial pancreas. Providing a comprehensive overview on the latest advances, this volume of Frontiers in Diabetes will be of particular interest to all healthcare providers involved in the daily management of patients with diabetes or related diseases.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Technological Advances in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes by D. Bruttomesso,G. Grassi,D., Bruttomesso,G., Grassi, Massimo Porta,Massimo, Porta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Glycemic Control

Bruttomesso D, Grassi G (eds): Technological Advances in the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes.

Front Diabetes. Basel, Karger, 2015, vol 24, pp 1-10 (DOI: 10.1159/000363460)

Front Diabetes. Basel, Karger, 2015, vol 24, pp 1-10 (DOI: 10.1159/000363460)

______________________

Glucose Control in Diabetes: Targets and Therapy

Geremia B. Bolli · Francesca Porcellati · Paola Lucidi · Carmine G. Fanelli

Department of Medicine, University of Perugia Medical School, Perugia, Italy

______________________

Abstract

In 1993, the Diabetes Control Complications Trial (DCCT) study established that chronic hyperglycemia initiates and progresses to microvascular complications such as retinopathy in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). The milestone message from DCCT has been that early near-normalization of blood glucose in recent-onset T1DM with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) <7.0% prevents the appearance and delays progression of microvascular complications. To achieve this, the physiological model of insulin substitution is needed with basal insulin for the fasting state and prandial insulin at each carbohydrate meal. This can be achieved with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), the gold-standard approach to substituting basal insulin, or multiple daily insulin injections (MDI) using long-acting insulin analogues as basal insulin (glargine or degludec once a day, detemir twice a day) with very similar results. Neutral protamine Hagedorn should be totally dismissed in the treatment of T1DM. It does not really matter whether CSII or MDI is used, as long as HbA1C is maintained <7.0% in each treatment. Unfortunately, only a minority of T1DM patients reach this target. To increase the success of intensive treatment, education of diabetologists, the diabetes team, and the diabetic subjects on how to use insulin, diet, and physical exercise are strongly needed.

© 2015 S. Karger AG, Basel

The Question of Origin of Microangiopathy in Diabetes Mellitus

History

In 1993, the Diabetes Control Complications Trial (DCCT) [1] provided us with the ideal targets of intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). The DCCT was a milestone study which answered in a clear and definitive manner the long-asked question of whether the microvascular complications of diabetes are due to chronic hyperglycemia or rather to a genetic predisposition. The debate among opinion leaders had been going on for decades since the late vascular complications of diabetes were discovered in the early 1940s and 1950s in subjects with T1DM treated with insulin for 10-15 years. From its introduction in the clinics in 1922, it was clear that insulin saves lives, but, as life was prolonged, the surprise was the appearance of complications. The reason diabetic retinopathy was only first recognized in the 1940s was the simple fact that diabetic subjects did not live long enough to develop this complication before the discovery of insulin.

Today's young doctors and specialists have been living the ‘post-DCCT era’ and use the targets of DCCT to best prevent complications by aiming at near-normogly-cemia. However, they may not necessarily be familiar with the recent hot discussion concerning the origin of chronic vascular complications of diabetes. As early as in 1968, Siperstein et al. [2] introduced the hypothesis that microangiopathy in patients with diabetes was inherited and not acquired after many years of uncontrolled hyperglycemia. On the other hand, large epidemiological observations [3] and experimental evidence in animals [4] have suggested that chronic hyperglycemia is behind the development of microangiopathy, especially retinopathy. In 1983, there was a debate in the New England Journal of Medicine between those in favor of the genetic versus the metabolic (hyperglycemia) hypothesis to explain microangiopathy in diabetes [5]. Clearly, only a randomized, controlled, intervention trial comparing the effect of near-normal versus elevated blood glucose on appearance and progression of micro-angiopathy in subjects with T1DM could ultimately answer this key question and end the decades-long controversy. This trial was the DCCT [1]. The DCCT was designed to ultimately guide diabetologists and subjects with T1DM alike on how to control hyperglycemia and at which level to keep it long term in order to prevent later complications and/or progression of complications. A few years later in 1998, the results of another trial on blood glucose control and complications, this time in subjects with T2DM, were reported in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) [6].

The Trials of Glucose Control on Microangiopathy: The Common Messages from the DCCT and UKPDS

The core messages from the DCCT and UKPDS should be emphasized because they are, and will always be, relevant for everyday practice in the diabetic clinic. Whenever we sit in front of our patients with T1DM or T2DM and have to establish a treatment strategy of blood glucose management, we base our decisions on the messages from the DCCT and UKPDS.

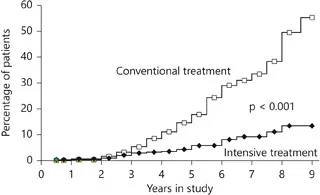

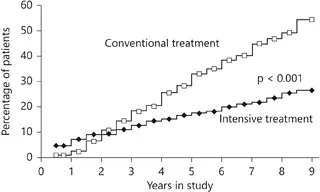

First, the chronic elevation of blood glucose, not genetics, is responsible for micro-angiopathy (and macroangiopathy). Figures 1 and 2 present results on risk for developing retinopathy, and similar results have also been obtained for neuropathy and nephropathy. Genetics may explain the variance of effects of chronic hyperglycemia in different individuals who develop different degrees (severity) of micro/macroangiopathy. Microangiopathy, however, does not develop when blood glucose is normal, it develops only after years of hyperglycemia. Thus, chronic hyperglycemia is the necessary and nearly always sufficient condition for the development of microangiopathy (although there is a restricted minority of individuals genetically protected by hyperglycemia who do not develop complications). As mentioned earlier, genetics by itself cannot result in microangiopathy as long as blood glucose is normal - genetics can only modulate the negative effects of chronic hyperglycemia. Second, the prospective benefit of lowering mean blood glucose over time is relevant to subjects with new diabetes onset (and thus no complications at baseline), as well as to those presenting with initial complications due to several years of diabetes. Third, lowering blood glucose, this time in T2DM as shown by the UKPDS [6], is as beneficial as it is in T1DM on appearance and progression of microangiopathy. Fourth, in the extension of the DCCT (EDIC), subjects have been monitored for nearly 20 years with no additional intervention [7]. Interestingly, in the intensive group, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) increased from 7.0 to 8.0%, whereas in the control group it decreased from 9.0 to 8.0%. So, in the EDIC follow-up of DCCT, HbA1C is quite similar between the two groups of the DCCT study. The surprising observation has been that the originally intensive group continues to benefit from the antecedent good glycemic control of the DCCT with less microangiopathy despite deterioration of blood glucose. In contrast, the original control group continues to develop more microangiopathy despite improved glycemic control. Fifth, the EDIC study has also examined cardiovascular events (macroangiopathy) in addition to microangiopathy. After 15 years of follow-up, the original intensive group presented lower numbers of cardiovascular events and greater survival.

Fig. 1. Cumulative incidence of retinopathy (3-step progression) in the DCCT study, primary prevention cohort [1]. When near-normoglycemia is established and early clinical onset of T1DM and HbA1C is at or below 7.0%, corresponding to a mean blood glucose of 140 mg/dl (intensive treatment), retinopathy appears at the end of 9 years only in a small percentage of subjects. In contrast, in subjects in whom blood glucose is maintained elevated (220 mg/dl, HbA1C about 9.0%), retinopathy appears already after 3 years and nearly all subjects are affected after a few years. Reproduced with permission from the New England Journal of Medicine.

Fig. 2. Cumulative incidence of retinopathy (3-step progression) in the DCCT study, secondary intervention cohort [1]. These are subjects with retinopathy at baseline already after a few years of T1DM. When near-normoglycemia is established and HbA1C is at or below 7.0%, corresponding to mean blood glucose of 140 mg/dl (intensive treatment), retinopathy progresses less as compared to the standard group in which blood glucose is maintained elevated (220 mg/dl, HbA1C about 9.0%). Reproduced with permission from New England Journal of Medicine.

Taken together, the above findings are the basis of our current understanding on how to treat diabetic subjects with T1DM to prevent microangiopathy. In subjects with newonset T1DM, the goal is achieving (quickly) and maintaining near-normoglycemia (for decades) to prevent microangiopathy which otherwise appears after a few years, and to prevent macroangiopathy 10-20 years later. In subjects with several years of T1DM and already established complications, it is still important to lower hyperglycemia and maintain HbA1C at about 7.0% to prevent the progression of microangiopathy. The same applies to T2DM and suggests that hyperglycemia is a common vascular poison to micro vessels regardless of the origin of hyperglycemia (T1DM, T2DM, or secondary diabetes; fig. 3). The benefits of lowering blood glucose extend after 10-15 years to macroangiopathy as well, which, again, is true for both T1DM [7] and T2DM [8].

Blood Glucose Targets

The current blood glucose targets that we have adopted for the treatment of diabetes mellitus are derived from evidence of protection against onset or progression of microangiopathic complications in the DCCT (for T1DM) [1] and UKPDS (for T2DM) [6]. As previously...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- Glycemic Control

- Home Blood Glucose Monitoring

- Continuous Glucose Monitoring

- Insulin Delivery System

- Closed-Loop Insulin-Delivery System

- Alternatives to Insulin Injection

- Devices to Support Treatment Decisions

- Electronic Medical Record

- Author Index

- Subject Index