- 136 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cosmetic Photodynamic Therapy

About this book

Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) has become an important treatment modality in medical practice. New and exciting applications continue to emerge and the future of PDT looks brighter and brighter. Dermatologists and other health professionals around the world rely on its therapeutic effect for the treatment of actinic keratoses, non-melanoma skin cancers, acne vulgaris, and various other dermatologic conditions. In this comprehensive yet concise book, world-renowned experts showcase all of the common, everyday uses of PDT in dermatologic offices. They also examine how this beneficial therapy can be utilized to its full capacity. The considerable knowledge presented here renders this publication an indispensable resource for all dermatologists and health professionals who offer their patients this effective, noninvasive procedure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cosmetic Photodynamic Therapy by M. H. Gold,M.H., Gold, D. J. Goldberg,D.J., Goldberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Family Medicine & General Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Gold MH (ed): Cosmetic Photodynamic Therapy. Aesthet Dermatol. Basel, Karger, 2016, vol 3, pp 8-35

DOI: 10.1159/000439328

DOI: 10.1159/000439328

______________________

Photodynamic Therapy in Treating Actinic Keratosis and Photorejuvenation

Jennifer D. Petersona · Mitchel P. Goldmanb

aSuzanne Bruce and Associates, Katy, Tex., and bGoldman, Butterwick, Fitzpatrick, Groff, and Fabi, San Diego, Calif., USA

______________________

Abstract

The first photosensitizer prodrug to be FDA approved for use in topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) was aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Studies investigating the treatment of nonhyperkeratotic actinic keratoses (AKs) with ALA-PDT have led to multiple advances and refinements in treatment over the last decade. Incubation times of ALA have decreased, multiple light sources have been used to elicit the reaction, and cosmetic benefits of treatment have been discovered. In the following chapter, the background of ALA-PDT will be reviewed and clinical studies regarding the treatment of AKs and photorejuvenation are summarized. Finally, a practical guide for ALA-PDT treatment is provided in order to optimize treatment while avoiding common pitfalls of treatment.

© 2016 S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

The first photosensitizer prodrug to be FDA approved for use in topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) was 5-δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). Studies investigating the treatment of nonhyperkeratotic actinic keratoses (AKs) with ALA-PDT have led to multiple advances and refinements in treatment over the last decade. Incubation times of ALA have decreased, multiple light sources have been used to elicit the reaction, and cosmetic benefits of treatment have been discovered. In the following chapter, the background of ALA-PDT will be reviewed and clinical studies regarding the treatment of AKs and photorejuvenation are summarized. Finally, a practical guide for ALA-PDT is provided in order to optimize treatment while avoiding common pitfalls of treatment.

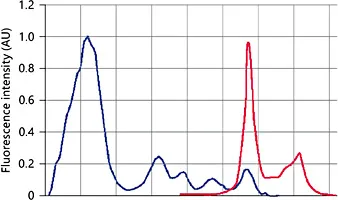

Fig. 1. Porphyrin absorption curve displays maximum absorption in the Soret band (360-400 nm) followed by 4 smaller peaks between 500 and 635 nm (Q bands). AU = Arbitrary units.

Background

The first topical porphyrin derivative, ALA, a natural precursor of protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) in the heme pathway, was introduced in 1999 by Kennedy et al. [1]. ALA acts as a prodrug-photosensitizing agent with the ability to penetrate the stratum corneum of the skin and be absorbed by actinically damaged skin cells and pilosebaceous units, whereas PpIX is the actual photosensitizer. Years later, a lipophilic ALA ester derivative, methyl aminolevulinate (MAL), was developed, showing stronger porphyrin fluorescence and better tumor selectivity, most likely because of enhanced penetration through cellular membranes compared with the hydrophilic ALA [2]. Recently, Ko et al. [3] showed no significant differences in complete response rates, recurrence rates, or cosmetic outcomes 12 months after PDT treatment of AKs with ALA or MAL; however, subjects reported ALA-PDT was more painful than MAL-PDT.

Mechanism of Action

Porphyrins exhibit a maximum absorption in the Soret band (360-400 nm) followed by 4 smaller peaks between 500 and 635 nm (Q bands; fig. 1) [4]. PDT involves the activation of a photosensitizer by light in the presence of an oxygen-rich environment. Topical PDT involves the application of ALA or MAL to the skin for some time, known as incubation time. This leads to the conversion of ALA to PpIX. PpIX accumulates in rapidly proliferating cells of premalignant and malignant lesions [5], as well as in blood vessels, melanin, and sebaceous glands [6]. Upon activation by a light source and in the presence of oxygen, the sensitizer (PpIX) is oxidized, a process called ‘photobleaching’ [7]. During this process, free radical oxygen singlets are generated, leading to selective destruction of tumor cells by apoptosis without collateral damage to surrounding tissues [8, 9].

Fig. 2. In the US, ALA is available as a 20% topical solution manufactured under the name Levulan® Kerastick® (DUSA Pharmaceuticals).

Pharmacology

ALA is a hydrophilic, low-molecular-weight molecule within the heme biosynthesis pathway [5, 10]. In the US, ALA is available as a 20% topical solution manufactured under the name Levulan® Kerastick® (DUSA, Wilmington, Mass., USA; fig. 2). Since 1999, Levulan is FDA approved for the treatment of nonhyperkeratotic AKs on the face and scalp in conjunction with a blue light source, such as BluU (DUSA) [11]. It is supplied as a cardboard tube housing two sealed glass ampules, one containing 354 mg of ALA hydrochloride powder and the other 1.5 ml of solvent [12]. These separate components are mixed within the cardboard sleeve just prior to use.

Choice of Light Devices and Lasers

No standardized guidelines for the ‘optimal irradiance, wavelength and total dose characteristics for PDT’ exist according to the British Dermatology group and the American Society of Photodynamic Therapy Board [13-15]. However, certain laser and light sources are predictably chosen for PDT activation as their wavelengths correspond closely with the four absorption peaks along the porphyrin curve. The Soret band (400-410 nm), with a maximal absorption at 405-409 nm, is the highest peak along this curve for photoactivating PpIX. Smaller peaks designated as the ‘Q bands’ exist at approximately 505-510, 540-545, 580-584, and 630-635 nm [5, 6, 10]. There are advantages and disadvantages to exploiting the wavebands in either the Soret or Q bands for PDT. The Soret band peak is 10- to 20-fold larger than the Q bands, and blue light sources are often used to activate PpIX within this portion of the porphyrin curve, targeting lesions up to 2 mm in depth [16]. Longer wavelengths found within the Q bands produce a red light that penetrates more deeply (5 mm into the skin), but necessitate higher energy requirements [5, 10].

PDT light sources can be categorized in a variety of ways, including incoherent versus coherent sources, or by color (and wavelengths) emitted. Incoherent light is emitted as noncollimated light and is provided through broadband lamps, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and intense pulsed light (IPL) systems. Incoherent light sources are easy to use, affordable, easily obtained, and portable due to their compact size [17]. Lasers provide precise doses of light radiation. As a collimated light source, lasers deliver energy to target tissues at specific wavelengths chosen to mimic absorption peaks along the porphyrin curve. Lasers used in PDT include the tunable argon dye laser (blue-green light, 450-530 nm) [18], the copper vapor laser-pumped dye laser (510-578 nm), long-pulsed dye lasers (PDLs; 585-595 nm), the Nd:YAG KTP dye laser (532 nm), the gold vapor laser (628 nm), and solid-state diode lasers (630 nm) [19].

Actinic Keratoses

Therapeutic Strategies

Given the premalignant potential of AKs, early treatment is paramount to preventing disease progression. Treatment options for AKs depend on a variety of factors including severity of involvement, duration or persistence of lesions, patient tolerability or desire for cosmesis, affordability/insurance coverage, and physician comfort with available treatment modalities [20, 21]. While solitary or few lesions may be approached with localized treatments such as cryotherapy, curettage, excision, or dermabrasion, field treatment may be more appropriate when numerous lesions are identified. Field therapy has the advantage of simultaneously treating subclinical AKs. Chemical peels, laser resurfacing, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), topical diclofenac, topical retinoids, and topical immunomodulators (imiquimod) are all reasonable field treatment options in addition to PDT.

A comparison of PDT to other field treatment options for AKs yields comparable clearance rates [22, 23]. In fact, a comparison of 100% clearance rates from phase III clinical trials reported complete AK clearance with ALA-PDT in 72%, comparable to 5-FU (72%), and superior to imiquimod (49%) and diclofenac (48%) [24]. A direct comparison study by Kurwa et al. [25] found comparable lesion area reduction rates between ALA-PDT (73%) and 5-FU (70%). A recent meta-analysis evaluating AK clearance found 5-FU to be superior to PDT though PDT was felt to have similar results to imiquimod and ingenol mebutate. Finally, PDT was found to be more effective than cryotherapy or diclofenac [26].

Therapy Advantages/Disadvantages

Clearance rates of AKs following PDT have ranged from 68 to 98% [27, 28]. Assuming near equivalent or even superior clearance rates of PDT compared to other field treatment options, PDT has several advantages in the treatment of AKs. Improvement of photodamage, superior cosmesis, and better pa...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Front Matter

- A Historical Look at Photodynamic Therapy

- Photodynamic Therapy in Treating Actinic Keratosis and Photorejuvenation

- Topical Methyl Aminolevulinate-Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Actinic Keratoses and Photorejuvenation

- Photodynamic Therapy - Novel Cosmetic Approaches

- Photodynamic Therapy for Acne Vulgaris and Sebaceous Gland Hyperplasia

- Chemoprevention Using Photodynamic Therapy with Aminolevulinic Acid

- How I Use Photodynamic Therapy with 5-Aminolevulinic Acid in My Clinical Practice

- Author Index

- Subject Index