![]()

PART I

EARLY YEARS

![]()

ONE

“Growing Up in Two Worlds”

BALANCING JAPANESE AMERICA

WE hoed berries before we went to school. When we came back from school, we hoed berries 'til dark…. That was our life,” explained Harry Tamura. As farm kids who were the children of immigrants, Japanese American veterans in Oregon's Hood River valley grew up immersed in the robust work ethic of settlement farmers surviving in a new land. Their parents, struggling to eke out livings and support their families on small parcels of farmland, depended on their children's extra hands to manage the burgeoning farm chores. For Japanese American sons and daughters of all ages, work was necessary and expected.

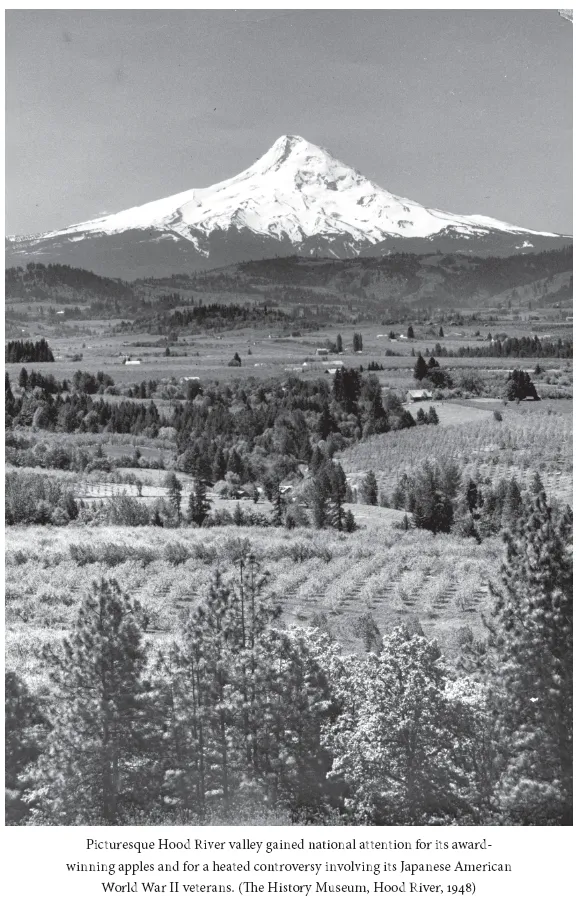

So fathers, mothers, sons, and daughters worked together on their family farms, scattered among fertile, volcanic bluffs along the eastern slope of the Cascade Range, sixty-six miles east of Portland. Their secluded valley, just ten miles wide and twenty-six miles long, nestled at the base of snowcapped Mount Hood to the south and extended northward to where rugged, basaltic columns one thousand to three thousand feet tall met the wind-whipped waters of the Columbia River. The stream called Hood River brought glacial water from the mountain, dividing the valley into what locals dubbed the East and West Sides.1 A river town formed at the nexus of its namesake and the Columbia River, served by river steamers and the Oregon Railroad. By the 1920s, the town had become a thriving business center, with two banks, three hotels, a railroad depot, a Carnegie library, six churches, telephone and electric service, a paid fire department, and fruit warehouses for its three thousand residents and valley farmers. In rural areas where most Japanese families lived, travel was cumbersome, and residents relied on services in their own small settlements, each with its own store, church, school, and often post office.2 From the 1920s, the lives of the future veterans were confined largely to farms in those separate locales: Oak Grove, Frankton, and Barrett to the west; Dee to the southwest; Odell, Mount Hood, and Parkdale to the south; and Pine Grove to the east.

“When we were small, we didn't do much [work],” recalled George Akiyama, the eldest of five Nisei whose family lived on an Oak Grove bluff west of town. “But when we were going to high school, our parents were just waiting for spring vacation!” Springtime meant hoeing strawberry plants, thinning clusters of young Bartlett and Anjou pears, or spading rills in the soil, allowing irrigation water to reach plants at the ends of rows. Through summer, Nikkei family members cut and packed bundles of asparagus spears, picked strawberries, and continued to irrigate family crops. In the fall, as young seedlings bore fruit, the family picked, sorted, and packed apples and pears. During the winter, they pruned the limbs of overgrown fruit trees, then picked up and burned the excess “brush.”

ISSEI FAMILY FOUNDATIONS

Their immigrant parents, the Issei, were Japanese nationals who had arrived in the United States near the turn of the twentieth century. Most intended to work on the West Coast only until they could earn enough money to buy land in Japan and secure their lives in their native country. Lured by exaggerated “get rich quick” myths, Issei males were intent on earning money quickly, and most expected to return to Japan as wealthy men within three to five years. First solicited as laborers for jobs that locals avoided, young Issei men drove heavy steel spikes in railroad ties; they also felled trees and used dynamite to clear heavy stands of conifers for landowners. Sometimes they received plots of stumpland or brushland scattered around the Hood River valley in exchange for their labor. Often they saved their meager earnings to purchase marginal land covered with stumps, brush, or swamp. Intent on maximizing the use of their land, they grew strawberries, cane berries, and asparagus as quick cash crops between their newly planted apple and pear seedlings. During those early years, some also took on second jobs or leased property from others.3

Eventually Issei realized that, in order to achieve financial success, they would need to work longer in the United States. So the middle-aged men married, adhering to traditional Japanese values that emphasized family unit and lineage. Those who could afford the expense returned to Japan to seek wives. Most chose a more economical route: arranging picture bride marriages by exchanging letters and photos with young women in Japan.

Destitute Issei newlyweds lived in hovels and worked exhaustively each day. George Akiyama explained that his father “cleared land for the orchards, pulled out those trees with stump pullers with a team of horses, blew out the trunks with dynamite, picked up all the roots, plowed and got the land ready for planting trees. While the trees were young, he raised asparagus. They had to have some income to keep them going.” His mother, as a new bride, worked alongside her husband on the farm. Every hand was needed to eke out a living.

FARM KIDS AND FAMILY VALUES

Not surprisingly, the second generation, the Nisei, grew up with orchards, fields, and barns as their playgrounds, while their mothers and older siblings worked nearby. As toddlers, Nisei climbed apple trees, played tag in the fields, and roasted volunteer potatoes [unplanted potatoes from reseeded plants] in the hot embers of bonfires for burning brush. When they grew older, Nisei children joined the family workforce. Shig Imai, the eldest of five sons, whose family farmed in Dee, lived eleven miles southwest of town. “Every time we had a minute,” he recalled, “we had to work on the farm, besides going to school.”

For immigrant families of all ethnicities, survival in a foreign land demanded cooperation and selflessness from every member, young and old. John Bodnar's book on immigrant history describes the need for immigrant parents and children to work together, share scant resources, and mute personal needs and wants in order to help their families achieve even a modest standard of living. Simply put, the family's welfare took priority over individual interests. (Bodnar did note that, unlike Issei women, the wives of Irish, Italian, and Greek immigrants did not work outside the home.)4

For young Sagie Nishioka, the eldest of three Nisei raised in Dee, those family responsibilities were overwhelming. After his father died when he was fourteen years old, Nishioka became head of the family for his mother and two young siblings. “Those were the days we had to do hard work,” he explained. “The hours were ten hours for a regular day…. We rented about ten acres for strawberries and seven acres just for pears and cherries…. I had to drive the horses to cultivate. We didn't have very much money, so we weren't able to buy a lot of machinery.” Work and family survival took precedence over school. “A lot of times I couldn't do homework because I was either too tired or had other things to do. Too many hours I was working, plus going to school. Because of this overload, I got sick.”

Shouldering such heavy family burdens, young Sagie rose at five in the morning to do his chores. After school, he returned to the family's strawberry fields until seven or eight at night. Only then did he manage to tackle his homework. He was thankful that an understanding teacher recognized the symptoms of overwork and often sent him home to rest.

As newcomers in an alien society, Issei raised their children according to the lifestyle they knew best: the customs, diet, values, and language of Japan. Nisei learned to manipulate grains of rice and pickled vegetables with their chopsticks; chant gochiso-sama (the food/drink was very tasty) after meals; mold rice cakes filled with sweet beans for New Year's Day; and chide one another using parental cautions such as da-me (don't). With Hood River's undulating terrain and poor country roads, Nikkei families, who lived far apart, rarely socialized during slack times on their farms. Bound by common language and customs, Nikkei families still gathered for New Year feasts at one another's homes and, after the 1920s, met for parties and games at Japanese community centers in downtown Hood River and in Dee.

Japanese families in the United States were influenced by Japan's Meiji era (1868–1912). After the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853 forced Japan to open to the West and the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown in 1868, Emperor Meiji's regime initiated a period of modernization. Japan began adapting Western models as it revamped its government, economy, legal system, communication and transportation networks, schooling, and military. By the early twentieth century, the small island country had emerged as the foremost Asian military power. It financed this rapid industrialization and military expansion, however, by levying heavy taxes on Japanese farmers, who were already burdened by poor harvests, low prices, and a strained economy. Most immigrants, including those from Hood River, came from southwestern Japan,5 where the population was growing, farms were already smaller per capita, and residents (considered to be of pirate and warrior stock) were viewed as “venturesome and enterprising.”6

Immigrants were buoyed by promising advertisements from emigration companies and encouraged by their own government. Many were younger sons whose elder brothers would inherit the family names and properties, others were elder sons determined to pay off family debts, and some were eager to avoid the military draft instituted in 1889. The majority of Hood River Nikkei families came from these farm families, beset by their country's economic and social pressures.7 And it was due to Issei investment in farming and the growth of their American-born children that they would stay in this country.

Norms that were prominent in Meiji Japan had roots in the country's long-standing feudal system and included both Confucian and Buddhist influences. The “family” (ie) was central to Japanese society. Both the family and Japanese society in general were organized around a hierarchical structure. Status in society was based on a clear class system and prescribed roles imbued with a deep sense of duty to one's superiors; the husband and eldest son ranked at the top of the family hierarchy; family status was based on age and gender; and family members supported one another by emphasizing duty and obligation. Sociologist Harry Kitano observed that Issei were able to adapt more readily to their low status as immigrants in the United States because they had become accustomed to those roles in Japan. Therefore they easily transferred the deferential and compliant behaviors they had practiced in Japan to their relationships with America's “white man,” or hakujin.8

From their Issei parents, Nisei also learned the value of enryo, or practicing deference, reserve, and restraint in everyday behavior. They demonstrated this quality by turning down second helpings, even when they were still hungry, or by accepting a less desirable item, knowing someone else preferred the one they wanted. It appeared when they turned down offers of help or hesitated to impose on others, speak out, or ask questions. Nisei recognized the impact of “obligation” (on), feeling a duty to repay favors and gifts from friends, acquaintances, and family members. Heeding their parents' admonitions that the group's welfare took precedence over their own, Nisei learned to subordinate their wishes to those of siblings or friends. They learned how to avoid confrontation by keeping a low profile, staying in the background, and avoiding eye contact. They also acknowledged the value of a strong work ethic, especially one involving physical effort. In their new “culture of everyday life,” Nisei grew up learning typical Japanese behaviors by watching their parents, who modeled conformity, obedience, duty, reserve, and work.9

STRADDLING TWO CULTURES

Yet, while becoming familiar with the culture of their parents, Nisei were also citizens of the United States of America. As they grew older, they found themselves in an awkward position, as if each straddled the Pacific Ocean, with one foot planted in Japan and the other entrenched in American soil. “We had to grow up more or less in two worlds,” explained Shig Imai's younger brother Hit (Hitoshi). “Our parents had their ways and we had our ways.” Affirming Nisei upbringing in two societies, sociologist Thomas D. Murphy noted that much of what the Nisei learned in one society they were expected to forget or disregard in the other.10 These “ways” of the Nisei were not unique, for they could be likened to those of other second-generation Americans, according to Marcus Lee Hansen, the Norwegian American historian considered the father of immigration history. Acting on their standing as American citizens, the children of immigrants tended to reject their parents' heritage in favor of newly learned American traditions, in effect, becoming marginal in both societies.11

For Nisei, language became the most obvious challenge, apparent from the first day of school. “When I started first grade, I'm sure the only English words I knew were ‘hello’ and ‘good-bye,’” recalled Mam Noji, the eldest of four siblings. His family and three others shared a cramped home in Parkdale, fourteen miles south of town, in the direction of Mount Hood, until the Nojis moved to the second floor of their new barn. Few working Issei parents, including the Nojis, had the time or opportunity to learn English. As a result, families spoke Japanese almost exclusively at home. Even as Nisei learned English at school and from white classmates, they were limited to speaking Japanese when conversing with their parents. As Hit Imai rationalized, “Anytime I spoke English to my parents, they figured I was talking something bad.”

Younger Nisei, following in the footsteps of older siblings, often found that their transition to school was easier. Harry Tamura's older brother, George, explained, “My folks were pretty strict about speaking Japanese at home. Dad said, ‘When you're at home, you speak Japanese. When you go outside, speak American because you're in America.’ But when I went to school in the first grade, all I could speak was Japanese. I flunked because I couldn't speak. Dad and Mom were so embarrassed…but they understood why.” Since Tamura's father had studied English in Portland, he tutored his son. “We started with ABCs and worked our way up. After that, I didn't have any trouble.” Brother Harry and two younger siblings benefited from George's lessons.

Most Hood River Issei were literate, and many had completed more than the six years of education mandatory in Japan after 1908. They valued education and citizenship as ways of helping their children to succeed and overcome discrimination, encouraging Nisei to “listen to the instructors carefully,” “do whatever the teacher [says],” and “study hard so [you will] not get behind.”

At school, however, other cultural differences became apparent. During the early years, Santa ignored the homes of Nikkei children, who also received Valentines from classmates but did not give any themselves.12 At school, Nisei noticed that their white peers were already familiar with nursery rhymes read by their teachers. Classmates talked animatedly about visiting their grandmothers and grandfathers, concepts unfamiliar to Nisei, for the o-baachan and o-jiichan their parents spoke of were merely strangers in distant Japan. Then, too, their parents, hampered by the language barrier, rarely attended school meetings and joined them only for special exhibits of their artwork or writing.

Yet, as Nisei began to notice differences between their families' ethnic traditions and those of their white peers, shame, embarrassment, and even defiance often emerged. For some, it was easy to blame those differences on not being white. “I think we were kind of ashamed of being Japanese,” admitted George Akiyama's younger brother Sab (Saburo). “During Depression years, you know, we couldn't afford to buy bread, so my mother used to make rice balls for lunch. Kids teased us about eating fish eggs and rice. We used to tell them...