![]()

1 / Tsawalk

THE CENTRALITY OF WHALING TO MAKAH AND NUU-CHAH-NULTH LIFE

STORIES CONTAINED WITHIN INDIGENOUS ORAL TRADITIONS PROvide a window into Native societies and cultures, helping to define and explain their way of life. In Nuu-chah-nulth and Makah oral tradition, a story has been passed down from one generation to the next, one that is central to our identity as whalers. T’iick’in, the great mythical Thunderbird, was the first great whale hunter. The flapping of his wings caused thunder and his flicking tongue brought lightning. There were once four Thunderbirds that lived in our area, but three of them were killed by Kwatyat, the creator of all things. T’iick’in was known to feed on whales (iiḥtuup). He utilized Itl’ik, Lightning (Sea) Serpent, as a kind of harpoon or spear to throw at a whale to stun it. Once he had dazed the whale, T’iick’in swooped down and picked it up in his mighty claws and took it back to the mountains, where he enjoyed a feast of succulent whale meat and blubber. T’iick’in demonstrated that the iiḥtuup could be caught and utilized for food and tools.1

In another version of this story, Thunderbird and whale saved the Nuu-chah-nulth people from starvation. It was a very bad season for fishing and people were having a difficult time finding food to eat. Thunderbird saw how hungry we were and went out in search of a whale. He took Lightning Serpent and wound it around his waist as he flew along the coast hunting for a whale. Finally, he spotted one, and he took the serpent and threw it down at the whale, hitting and stunning it. While the whale was stunned, it remained floating on the surface of the water, making it easy for Thunderbird to grab. Thunderbird dived down, picked up the whale in his powerful talons, and brought it to the village for all the people to eat, so that they would no longer be hungry.2

I heard Thunderbird, Whale, and Lightning Serpent stories when I was a young girl. The legends have been passed down the generations and throughout the years have been recorded by ethnologists, anthropologists, and historians. There are many different versions, but they all contain the same message: the whale was, and still is, central to our culture and identity. In this chapter, I discuss how, before the arrival of the mamalhn’i, whaling traditions were central to our very existence as a people and were intricately connected to Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth economic, political, religious, and social systems.

MAKAH AND NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURAL SYSTEMS

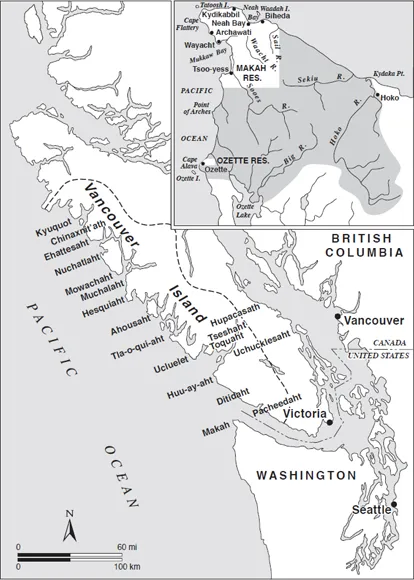

The Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples’ traditional territory is on the central Northwest coast, the Makah in the Cape Flattery area at the northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State and the Nuu-chah-nulth on the west coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia. Topographically, the Makah’s and Nuu-chah-nulth’s traditional territory consists of steep and rocky terrain, with the Coast mountain range in British Columbia and the Cascades mountains in Washington and Oregon acting as natural dividers, cutting off these seafaring, maritime peoples from the inland hunting-and-gathering societies. These natural boundaries surrounding the various indigenous groups resulted in a large number of small, autonomous societies along the coast.3

The Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth are among the Wakashan-speaking peoples, sharing linguistic ties, cultural patterns, and a tradition of hunting whales. Early explorers’ accounts noted the similarities in Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth social organization, language, subsistence patterns, and ceremonialism.4 Since the Makah are the only tribe in the United States who speak the Wakashan language, this led some scholars to suggest that they moved to the Cape Flattery area from Vancouver Island. This conjecture is supported by both Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth oral histories, which not only link the two groups but also provide a clue as to how the tribes became territorially disconnected. This is a story passed down through the Makah oral tradition and recorded by James Swan, the first non-Indian to live among the Makah in the mid-1800s.

A long time ago . . . the water of the Pacific flowed through what is now swamp and prairie between Waatch village and Neah Bay, making an island of Cape Flattery. The water suddenly receded, leaving Neah Bay perfectly dry. It was four days reaching its lowest ebb, and then rose again without any waves or breakers till it had submerged the Cape, and in fact the whole country except the tops of the mountains at Clyoquot. The water . . . as it came up to the houses, those who had canoes put their effects in them, and floated off with the current, which set very strongly to the north. Some drifted one way, some another; and when the waters assumed their accustomed level, a portion of the tribe found themselves beyond Nootka, where their descendents now reside, and are known by the same name as the Makahs.5

Territory of Nuu-chah-nulth and Makah groups. Adapted by Barry Levely from HuupuKw anuum Tupaat: Nuu-chah-nulth Voices, ed. Alan Hoover (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2000). Inset: Mid-nineteenth-century Makah settlements. From Renker and Gunther, “Makah,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 7.

Although the two groups are separated by land, they are connected by the waterways that were the major travel routes of the coastal peoples. Historical evidence and oral history support the cultural linkages between the Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples. Archaeological excavations and carbon dating indicate that the Makah villages of Ozette and Wa’atch were occupied for at least 1,500 years. Radiocarbon dating shows that the Nuu-chah-nulth people have lived in their territory for more than 4,000 years.6

The Makah call themselves kwih-dich-chuh-ahtX, “people who live on the cape near the rocks and seagulls.” They received the name Makah, a word meaning “generous with food,” from their Clallam neighbors. The name was adopted by American officials in the 1850s. Before the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay brought all the Makah onto one reservation in Neah Bay, the Makah comprised several groups that were divided into five principal winter villages and two summer villages. The winter villages were Neah (Diah), which was on the site of an old Spanish fort; Wa’atch (Wayatch), on the south side of Cape Flattery; and Tsoo-yess (Tsu-yess, T’sues) and Ozette (Hosette, Osett), located at the Flattery Rocks. The fifth village, named Biheda (Bahaada, Ba’ada), was abandoned in 1852 following a smallpox epidemic. The summer villages were located at Klasset and Tatooche Island. In the post-1855 reservation period, all Makah eventually moved to the village site in Neah Bay.7

The Nuu-chah-nulth are a collection of village groups that are linked through a common language and similar cultural components. They were established as small, socially independent groups that came together in single villages. The members of these villages or local groups shared rights to the use of specific resources within geographically limited territories. The local groups were composed of ushtakimilh, or lineage groups, which had their own head, haw’ilth (chief), who represented the line of descent from an original ancestor. The village also had a taayii haw’ilth (head chief), who was from the highest-ranking ushtakimilh. Archaeological and historical evidence shows that the structure of the Nuu-chah-nulth villages continually changed during both the pre- and the post-contact periods. This was a result of tribal warfare over territory, resources, and after-contact disease epidemics, which ultimately led to amalgamations that transformed the villages into the fifteen distinct groups that exist today.8

My people were mistakenly called Nootka or Nootkans (also spelled Nutka), a name given to one of the Nuu-chah-nulth groups (Mowachaht) by Captain Cook when he visited the territory in 1778. The name was later extended to include all of the groups, including the Makah. At this time, we did not have one specific overarching name to define ourselves as a larger tribal group, but we had names for local groups that were linked to places of origin. Gilbert M. Sproat, a Scottish businessman who came to our territory—to what became known as the Alberni Valley—in 1860, referred to us as the “aht” people, which is the general ending of our ancestral names (Ahousaht, Tseshaht, Toquaht, etc.). “Aht” translates literally as “people of.”9 However, Cook’s name, Nootka or Nootkan, was the name that was eventually adopted by Canadian Indian agents, anthropologists, and others, and was used externally and internally to refer to these coastal groups.

My great-aunt Winnie (Winifred David) heard a story when she was a young girl about how we became known as the Nootkan people. She carried many of the stories she heard as a child into adulthood, thus continuing our oral tradition. As an elder, she was interviewed by numerous anthropologists and historians, and her remembrances were important in creating comprehensive written accounts of Nuu-chah-nulth culture and history. The story of how the Nuu-chah-nulth people got their erroneous name begins with Captain Cook and his initial visit to the region in 1778. Cook’s ship sailed into an area of Nuu-chah-nulth territory that he later named Nootka Sound. His ship came upon the Mowachaht village of Yuquot, which was renamed Friendly Cove by Cook. He was met by the local village members, who paddled out to the ship in their canoes in an attempt to help Cook’s crew navigate the rocks. The people yelled to the crew a word that sounds like Nootka, a word in our language that in English means “to circle about or around.” Aunty Winnie discussed this in an interview in 1977:

They started making signs and they were talking Indian and they were saying: nu-tka-icim nu-tka-icim, they were saying. That means, you go around the harbour. . . . So Captain Cook said, “Oh, they’re telling us the name of this place is Nootka.” That’s how Nootka got its name. . . . But the Indian name is altogether different. Yeah. It’s Yuquot, that Indian village. So it’s called Nootka now and the whole of the West Coast (Vancouver Island), we’re all Nootka Indians now.10

Throughout the years, the Nuu-chah-nulth groups on Vancouver Island worked at establishing a unified political voice for all the groups. In 1958, we formed a collective body and renamed ourselves the West Coast Allied Tribes (later changed to the West Coast District Council). A year after Aunty Winnie told her story to W. L. Langlois, the so-called Nootkan people officially adopted the more appropriate name of Nuu-chah-nulth, which means “all along the mountains and sea.”

WHALING AND NUU-CHAH-NULTH AND MAKAH ECONOMIES

Whalebones found in archaeological sites in Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth territories show that whales were significant to Native cultures as far back as 4,000 years.11 Before Native economies shifted following contact with mamalhn’i, Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth were marine people who derived most of their subsistence from the ocean, inlets, and nearby rivers. The people fished primarily for halibut and salmon, harvested the local shellfish, and hunted sea mammals. While they did not focus on developing land resources for subsistence, they did hunt deer, bear, and elk and gathered roots and berries, which contributed to their diet. The majority of the food gathering took place during the summer months, and the two groups traveled to areas along the waterways where they could extract the resources; while there, they erected dwellings. As a result, these coastal peoples had both summer and winter residences: semi-permanent summer residences along the ocean and river shores, and more permanent winter houses also close to the waterways but in more sheltered areas to protect them from the harsh winter climate.

The Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth relied on the sea for most of their subsistence and placed much emphasis on hunting sea mammals, such as seals, sea lions, and whales. Archaeological data provide evidence that their greatest economic resource was whaling.12 Early historical documentation gives varying non-Native viewpoints on the economic significance of whaling. Some early writers suggested that the prestig...