![]()

V

Banded Penguins

Genus Spheniscus

![]()

FIG. 1 African penguin pair showing the broad white neck-band characteristic of the species. (J. Kemper)

13

African Penguin

(Spheniscus demersus)

ROBERT J. M. CRAWFORD, JESSICA KEMPER, AND LES G. UNDERHILL

1. SPECIES (COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES)

African penguin, Spheniscus demersus

The African penguin is also known as the blackfooted penguin and the jackass penguin.

2. DESCRIPTION OF THE SPECIES

ADULT. Face, throat, crown stripe, nape, and upperparts are black, including the upper flipper. The underparts are mostly white. A broad white supercilium runs from in front of the eye, around the back of the face, and to the neck and joins the white breast (fig. 1). A black stripe runs up the side of the body and across the upper breast. Some birds have a second black band on the neck. The chest and abdomen have a variable number of irregular black spots. The black plumage becomes browner with wear. A patch of naked pink (rarely black) skin above the eye is white and feathered immediately after molt. The bill is black with a vertical pale horn band at the gonys. Eyes are brown; legs and feet are black with pink blotches.

IMMATURE. Plumage is the same as the juvenile’s but fades to gray and then brownish before molt. Some individuals undergo partial head molt at sea before complete molt into adult plumage; the extent varies from the supercilium to the entire head and upper body to the level of the breast-band.

JUVENILE. Plumage is blue gray on the upperparts, shading to white below. The chin and lower throat are gray. There are few darker spots on the breast and flanks. Legs and feet are pale flesh (Ryan et al. 1987; Randall 1989; Hockey et al. 2005).

MEASUREMENTS. In general, males are larger than females, but measurements overlap. See table 13.1.

3. TAXONOMIC STATUS

No subspecies are recognized. The species is one of four in the genus Spheniscus. The Magellanic penguin (S. magellanicus) occurs as a rare vagrant off southern Africa: it is larger, always with two breast-bands (like some African penguins), a broader upper band, narrower white supercilium, less pink on the face, and a diagnostic thin white line at the base of the bill that is absent in the African penguin.

4. RANGE AND DISTRIBUTION

The African penguin is endemic as a breeding species to southern Africa, where it breeds at 28 localities between Hollamsbird Island, Namibia, and Bird Island, South Africa (fig. 2) (Kemper et al. 2007c). Of these localities, 11 are in Namibia, 11 in the Western Cape, and 6 in the Eastern Cape. The usual nonbreeding range extends along some 3,200 kilometers of coast between about 18° south on the Namibian coast and 29° south on the coast of KwaZulu-Natal. Vagrant birds have been recorded north to Sette Cama (2°32´ S), Gabon, on the West African coast (Malbrant and Maclatchy 1958), to the Limpopo River mouth (25° S), and to Mozambique on the east coast (Shelton et al. 1984). This species has have been recorded up to 100 kilometers offshore (Rand 1960), but most occur within 20 kilometers of the coast (Wilson et al. 1988), except on the Agulhas Bank, where the distribution of their prey extends farther offshore (Shelton et al. 1984).

FIG. 2 Breeding distribution and abundance of the African penguin, with counts based on pairs. Extinct colonies are not shown, nor are all extant colonies shown.

5. SUMMARY OF POPULATION TRENDS

Breeding colonies of African penguins are grouped in three regions: Namibia in the north and South Africa’s Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces in the south. Colonies in the Western Cape are separated from those in the other two regions by distances of about 600 kilometers.

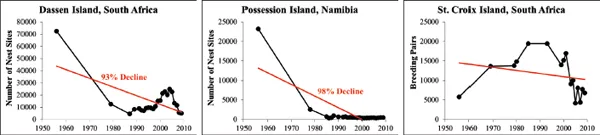

According to Namibia’s Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR), African penguins breeding in Namibia decreased from 49,000 pairs in 1956–57 to 12,000 pairs in 1978–79 and 4,500 pairs in 2009–10 (MFMR, unpubl. data). In the Western Cape, there may have been close to 1 million pairs at Dassen Island in the 1920s (Crawford et al. 2007). Some 92,000 pairs bred in this region in 1956, decreasing to 41,000 pairs in 1978, 34,000 pairs in 2001, and 11,000 pairs in 2009 (Crawford et al. 2011). In the Eastern Cape, numbers increased from about 6,000 pairs in 1956 to an average of 22,000 pairs from 1985 to 2001 and then decreased to an average of 10,000 pairs from 2003 to 2009 (Crawford et al. 2009). The population trends for Namibia, the Western Cape, and the Eastern Cape are illustrated by the number of nests reported for Possession, Dassen, and St. Croix Islands (fig. 3). The overall population may have been on the order of 1 million pairs in the 1920s but decreased to about 147,000 pairs in 1956–57. It fell to about 75,000 pairs in 1978, 63,000 pairs in 2001, and 25,000 pairs in 2009 (Crawford et al. 2011).

FIG. 3 Population trends of nests in African penguin colonies: (a) Dassen Island, South Africa; (b) Possession Island, Namibia; (c) St. Croix Island, South Africa.

FIG. 4 African penguin colony at Boulders Beach, South Africa, showing the boardwalk for visitors and some nesting penguins. (P. Ryan)

6. IUCN STATUS

The International Union for Conservation of Nature upgraded the species to Endangered on its Red List of Threatened Species in 2010 because of a large, sustained decrease in the 20th century, at a rate of 13% per generation since 1976 (IUCN 2011; Ellis et al. 1998; Kemper et al. 2007c). The breeding population has decreased by more than 50% in the three most recent generations and continues to decline. A large decrease in South Africa, from 57,000 breeding pairs in 2001 to 21,000 pairs in 2009, halved the global population in the 21st century.

The species is a specially protected bird in Namibia and is included in Appendix 2 of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and Appendix 2 of the Convention for the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service lists it under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

7. NATURAL HISTORY

BREEDING BIOLOGY. Coastal islands represent 24 out of 28 extant breeding localities. Caves are used at 2 localities on the Namibian mainland (Loutit and Boyer 1985; Bartlett et al. 2003; Simmons and Kemper 2003), and there are 2 mainland localities in South Africa’s Western Cape, although occasional breeding has been attempted at other coastal sites. Breeding is usually colonial (fig. 4), but solitary nests occur. Both sexes build nests in burrows in guano or sand, in clefts between rocks, in disused buildings, and on the surface, preferably under shade (Shelton et al. 1984; Crawford et al. 1995a; Kemper et al. 2007d). African penguins make scrapes and dig burrows by pushing sand backward with their feet (Eggleton and Siegfried 1979). Burrows have a more constant microclimate than surface nests. In burrows, relative humidity is higher, air temperatures fluctuate less, wind effect is negligible, and birds are not exposed to direct sunlight (Frost et al. 1976a) (fig. 5). Nesting material includes seaweed, pieces of vegetation, rocks, shells, bones, and feathers, but some nests are not lined.

FIG. 5 Adult African penguin panting to keep cool while incubating a clutch of two eggs. (P. Ryan)

Breeding is monogamous. At St. Croix Island, 80–92% of birds whose mates did not disappear bred with the same mate in the following breeding season; 89% of males and 78% of females returned to breed at the same site (Randall 1983). At Robben Island, over a four-year period, 80 of 85 adults retained the same mate; for the other 5, at least one partner had died. In the same period, 53% of 85 adults nested at the same site, 44% used two sites, 2% used three sites, and 1% used four sites (Crawford et al. 1995a). Breeding locality fidelity is strong, with no confirmed records of adults breeding at more than one locality. However, first-time breeders may choose to breed at localities or colonies other than their natal site, having the flexibility to emigrate and hence to take advantage of long-term changes in the distribution of food (Shelton et al. 1984; Crawford 1998; Crawford et al. 1999).

The clutch is usually two eggs, sometimes one, and rarely three (Crawford et al. 1999, 2000b). The egg is a rounded oval and white, becoming stained as incubation proceeds. Egg size and dimensions are shown in table 13.2. “Runt” eggs are laid occasionally. The laying interval is 3–3.2 days (Williams 1981; Williams and Cooper 1984). Lost clutches may be replaced, and successful breeders may re-lay (Randall and Randall 1981; La Cock and Cooper 1988). Incubation starts with the first-laid egg, lasts 38–41 days (about 37–38 days per egg), and is shared equally by both sexes (Rand 1960; Williams and Cooper 1984; Randall 1989). The incubation shift for eggs hatched successfully is 1–2 days; for eggs eventually abandoned, it is 1–14 days. Mean hatching interval is 2.1 days (Williams and Cooper 1984).

The newly hatched chick is blind, helpless, and covered in a sooty gray protoptile down (Randall 1989). Mass at hatching is about 72 grams (Williams and Cooper 1984). Chicks are brooded by adults until about 10 days after hatching, at which time secondary down starts to develop. They are partly covered by adults until about 15 days (fig. 6). After 16 days, they are able to sit beside their parents (Seddon and van Heezik 1993). Chicks reach full thermoregulatory capacity at a mass of about 400 grams, which they attain at 21–25 days (Erasmus and Smith 1974). From 26–30 days, they are often left unguarded and may form crèches of up to 25 chicks. At 31–35 days, contour feathers start to grow beneath the down. Chicks have full juvenile plumage from 61–65 days and fledge when between 55–130 days old (Seddon and van Heezik 1993; Kemper 2006). Mortality of chicks aged 0–34 days is due primarily to burrow collapse, exposure, drowning, accidental death in the nest, and predation by kelp gulls (Larus dominicanus); from 42–90 days, it is mostly from starvation or heat stress (Seddon and van Heezik 1991; Kemper 2006). The daily food intake of chicks increases from about 250 grams at 20–30 days to about 500 grams at 40–50 days (Cooper 1977). Most feeding of chicks takes place in the afternoon. Growth of two chicks in the same brood is similar for the first 25 days, after which the growth of the B-chick lags behind that of the older sibling and returns to...