eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Enlightenment and Exploration in the North Pacific, 1741-1805

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Enlightenment and Exploration in the North Pacific, 1741-1805

About this book

Saluting an era of adventure and knowledge seeking, fifteen original essays consider the motivations of European explorers of the Pacific, the science and technology of 18th-century exploration, and the significance of Spanish, French, and British voyages. Among the topics discussed are the quest by enlightenment scientists for new species of plant and animal life, and their fascination with Native cultures; advances in shipbuilding, navigation, medicine, and diet that made extended voyages possible; and the lasting significance of the explorers' collections, artworks, and journals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Enlightenment and Exploration in the North Pacific, 1741-1805 by Stephen W. Haycox, James K. Barnett, Caedmon Liburd, Stephen W. Haycox,James K. Barnett,Caedmon Liburd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND

Spain’s Role in Pacific Exploration during the Age of Enlightenment

By the latter half of the eighteenth century, scientific inquiry had joined the established motives of territorial acquisition, commercial gain, and religious conversion as dominant themes for European exploration. The work of the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus,1 the writings of the French encyclopedists, the activities of the Royal Society of London, the founding of the American Philosophical Society, and worldwide interest in the transit of Venus had all left their imprint on the intellectual climate of the times. Europeans were similarly influenced by the concept of naturalism, the assumption that the whole universe of mind and matter was subject to and controlled by natural law. Its acceptance caused men of the Enlightenment to turn with enthusiasm to rediscovering their own lands: studying and recording natural resources and noting the customs and history of a region. Ancient authority was no longer sufficient to establish the truth of long-accepted propositions; everything on earth, and even beyond, was submitted to questioning and new investigation.

Men of the eighteenth century broke with Aristotelian tradition and adopted a method of inquiry based upon direct observation and reason. The critical spirit of the age inspired intellectuals to reevaluate previous knowledge and propose a geographical, historical, and statistical survey of the New World, one that would leave no corner uncataloged. This kind of scientific zeal existed in the leading countries of Europe, especially in England and France, and to a lesser extent in Sweden, Russia, Germany, Prussia, Italy, and the Netherlands. The young United States also participated. All had explorers and scientists in the field cataloging and pictorially reproducing the zoology, botany, and geography of the Old and New Worlds.2

Although much of this intellectual enthusiasm is well documented, general works on the European Enlightenment seldom include the accomplishments of Spain. Several factors combined to prevent Spanish scientists from receiving recognition for their achievements in discovering and classifying fauna and flora during the late eighteenth century. Even though expeditions started out with full government support, by the time of their return, the vacillating policies of Carlos IV (1788–1808) had resulted in court intrigues and international disputes. These problems plus the Napoleonic invasion all but ensured the obscurity of Spanish efforts, while those of England and France became better known throughout the world. Recently, however, as a result of the quincentenary and bicentennial celebrations of the voyages of Columbus and Malaspina, much has been done by Spanish researchers, as well as historians in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, to remedy the lack of information about Spain’s contributions. At the same time, with research continuing by scholars concentrating on English, French, Russian, American, and other nations’ activities, it is possible to show the interrelationships of the European and American scientific communities during the Age of Enlightenment.3

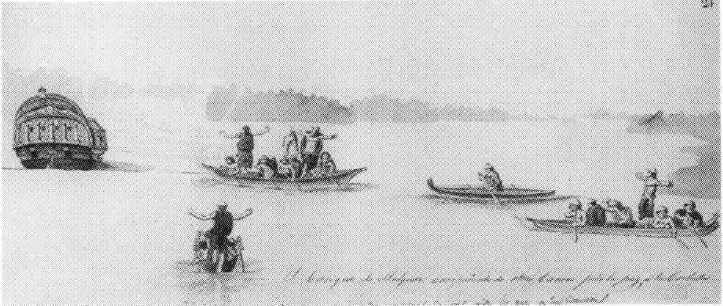

Chief of Mulgrave and his delegation greet Malaspina’s corvettes, seeking peace. Sketch probably by José Cardero, 1791. Museo de America, Madrid

In Spain, the subject of botany had commanded royal attention since the first Bourbon king, Felipe V (1700–1746), had requested all state officials in the Spanish empire to watch for unusual specimens of plants, animals, and minerals and send them to Madrid. He had also required two Spaniards, Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, to accompany a French scientific expedition to South America in 1735.4 Fernando VI (1746–1759) continued the crown’s interest in scientific inquiry and encouraged Ulloa to found a museum of natural history in Madrid in 1752. Fernando VI also saw to it that the Swedish botanist Pehr Loefling, a student of Linnaeus’s who had promoted his mentor’s works in Spain in 1751, be allowed to accompany a botanical expedition to Venezuela in 1754.5 Loefling followed the path set by Pehr Kalm, a fellow botanist who traveled through North America in 1748–51 seeking plants adaptable to the Swedish climate.6

Although the major reforming efforts of Carlos III were directed toward political and economic development, the enlightened Spanish king encouraged intellectual pursuits by sponsoring the establishment in Madrid of the Royal Botanical Garden, the Royal Academy of Medicine, and an astronomical observatory. Staff members of these centers assessed the accuracy of new knowledge and passed judgment on the new truths. Inspired by the work of Linnaeus and excited by the amount of information contained in Buffon’s encyclopedic Natural History of Animals,7 Spanish naturalists especially desired to apply new methods of identification to the botanical, zoological, and mineralogical resources of North and South America.

In France, the high regard for knowledge was shown by the publication during the years from 1751 to 1772 of the Encyclopédie; ou, dictionnaire raisoné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, generally edited by Diderot and d’Alembert and completed in seventeen large folio volumes. Throughout the work there was “an implication that the cause of humanity would be promoted not by the right theological doctrines, but by the right secular knowledge. Quietly and efficiently the supernatural sanctions on which the Ancien Regime rested were taken away.”8 In addition, Charles de Brosses in 1756 wrote Histoire des navigations aux terres australes, a major history of Pacific exploration that urged further examination (as well as colonial settlements) by France. It was translated into English by John Callander in 1766–68 without mention of the original author and substituting England for France in making a case for English expeditions.9

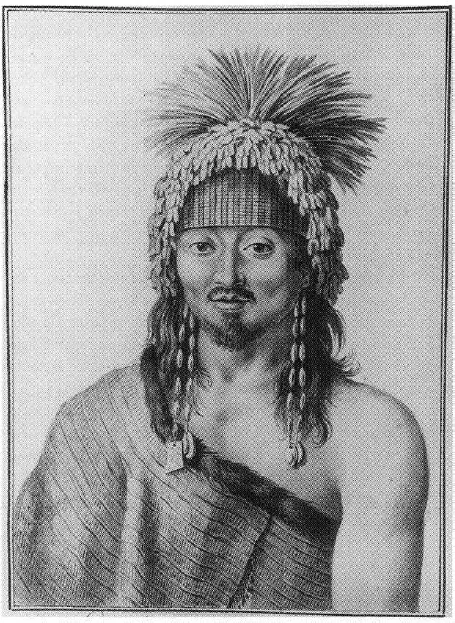

The chief of Descanso Bay on Gabriola Island. Ink and wash drawing by José Cardero. Museo de America, Madrid

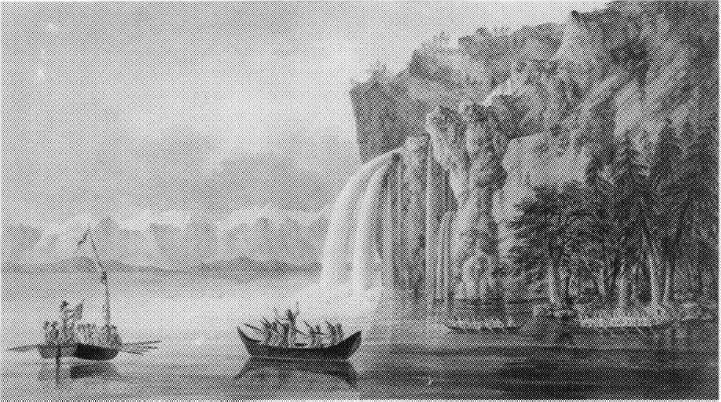

View of the Vernacci Channel inside the entrance to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, by José Cardero, 1792. Museo de America, Madrid

Louis Antoine de Bougainville, a French army officer who had served against the British with Montcalm at Quebec, was given command of a voyage of exploration around the world after France’s defeat in the Seven Years’ War. Bougainville, who had written a treatise on calculus and established his reputation as a diplomat and a scientist, took two ships with a two hundred-man crew and sailed across the Atlantic with scientific inquiry as a major goal.10 On board were the botanist Philibert de Commerson and the young astronomer Pierre Antoine Verón. They sailed from France on November 15, 1766, identified a flowering vine in South America that they named the bougainvillea, visited Tahiti, navigated through the Samoan and New Hebrides groups, sailed along the New Guinea coast, and rounded the Cape of Good Hope.

Bougainville completed the first French circumnavigation of the world on March 16, 1769.11 As he arrived home, James Cook of the British Royal Navy was already in the Pacific and bound for Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769. This event, measured from different stations around the world, would help scientists calculate the distance from the earth to the sun.12 Cook’s was the first of three British voyages that would eclipse everything that had gone before, both in the scope of new discoveries and in their contributions to science.

Captain Cook, commanding the Endeavour, sailed from Plymouth, England, on August 26, 1768, bound for Tahiti and to search for the fabled southern continent, Terra Australis, thought to lie somewhere in the southern ocean.13 With him were Joseph Banks, a wealthy young man with a passion for science; Daniel Carl Solander, a naturalist who had studied with Linnaeus; and Sydney Parkinson, an illustrator with a keen eye for detail. The political and geographical results of the voyage were of great importance, and the botanical results would have had at least a comparable effect had Banks and Solander been able to publish them within a few years of their return. Linnaeus believed that if the botanical plates were made available “the world would be … benefited by all these discoveries and the foundations of true science would be strengthened.”14

Unfortunately, the British had problems publishing the complete results, but interested persons, thanks to Banks’s generosity, were able to share in his home the descriptive text by Solander, the herbarium specimens, and the drawings by Parkinson, who died on the voyage. In November 1784 the text and the copper plates engraved after the drawings were close to completion, and Banks wrote that “all that is left is so little that it can be completed in two months.” But by that time Solander had been dead two years, and gone too were Cook and Linnaeus. International events prevented planned publication.15

Also in 1768, following a precedent of cooperation established with the French earlier in the century, Carlos III gave official sanction to a combined Franco-Spanish expedition of astronomers assigned to observe the transit of Venus in Baja California during June 1769. Responding to the urgings of British scientists who had sent Captain Cook to Tahiti, Spain appointed two qualified naval officers, Vicente Doz and Salvador Medina, to accompany the party of Abbé Chappe d’Auteroche from the Paris Academy of Science. Their destination was San José del Cabo, where, with the assistance of the Mexican-born astronomer Joaquín Velázquez de León, they set up their observatory, one of seventy-seven stations around the world. Despite the deaths of Chappe, Medina, and several other participants, results of the observations were successfully transmitted to Paris and coordinated with those of one hundred fifty-one other reporters. The English astronomer Thomas Hornsby in 1771 used the information to conclude the mean distance of the earth from the sun to be 93,726,900 English miles, a good estimate for the time.16

Captain James Cook circumnavigated the globe following his brief stay in Tahiti in 1769. He completed a second voyage around the world, sailing in the opposite direction, in 1775. On his third voyage of exploration, in 1778, the intrepid captain discovered the Hawaiian Islands and then sailed to the Pacific coast in search of a Northwest Passage. He entered Nootka Sound, anchoring in a bay he named Friendly Cove. Cook remained in the area for nearly a month, compiling a vocabulary of local words, investigating the surrounding country, and describing the Indians in some detail. He continued north along the coast of Alaska, continuing his many scientific endeavors. His survey concluded at the Arctic Ocean, where ice blocked further penetration. Failing to find a passage to the Atlantic, Cook turned his ships to the south and returned to Hawaii, where he was killed by hostile Natives at Kealakekua Bay on February 14, 1779.17

Spain, in the meantime, continued its pursuit of scientific interests. In 1777, the Spanish crown named the botanist Hipólito Ruiz as chief of an expedition designed to accomplish “the methodical examination and identification of the products of nature” in the viceroyalty of Peru. Accompanied by José Antonio Pavón (a fellow Spanish botanist), Joseph Dombey (a French naturalist with a doctorate in medicine), and two artists, Ruiz made an extensive examination of plant life throughout the viceroyalty and parts of Chile. Returning to Madrid in 1788, Ruiz and Pavón brought with them an impressive herbarium of dried specimens and one hundred twenty-four live plants for use in the royal botanical garden. Although plagued by financial difficulties and required to deal with Carlos IV in gaining royal support for their work, Ruiz and Pavón were able to publish three volumes of Flora peruviana et chilensis.18

In Santa Fé de Bogotá, capital of the viceroyalty of Nueva Granada, another Spanish botanist, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- Alaska and the North Pacific: A Crossroads of Empires

- Part 1: Motives and Objectives

- Part 2: Science and Technology

- Part 3: Outcomes and Consequences

- Contributors

- Index