![]()

1

Introduction

Gordon H. Orians, John W. Schoen, Jerry F. Franklin, and Andy MacKinnon

THE MAGNIFICENT COASTAL NORTH PACIFIC TEMPERATE RAINFORest, blanketing a glacially carved landscape of precipitous mountains and dashing rivers, fragmented by thousands of islands, surrounds the eastern Pacific Rim from southern Alaska to northern California. Rainforests and islands have been a major focus of ecological and evolutionary study over the last century and a half. Today they are a core concern of forest ecologists, conservation biologists, and others.

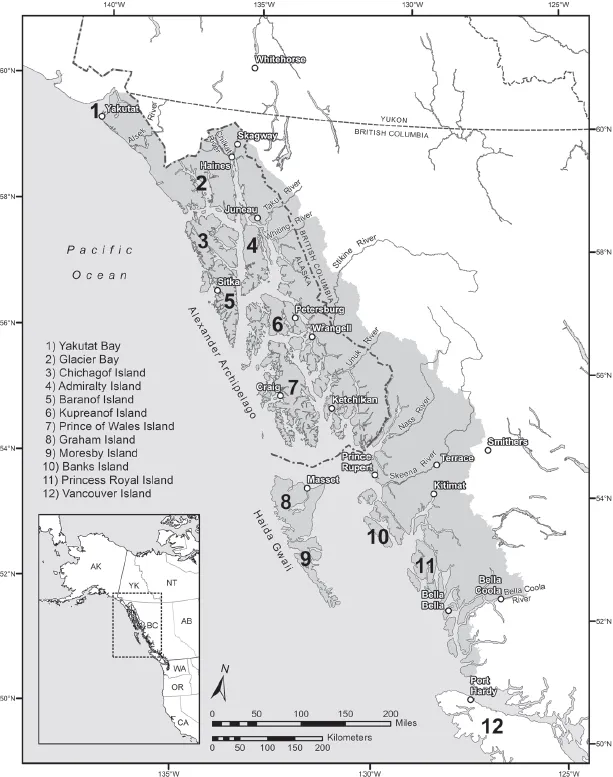

The purpose of this book is to provide a multidisciplinary overview of key issues related to the management and conservation of the portion of the coastal North Pacific rainforests in southeast Alaska and northern coastal British Columbia. This region (fig. 1.01), with its thousands of islands and millions of hectares of relatively pristine temperate rainforest, is home to nearly all the species it harbored before people arrived in North America. It thus provides a valuable opportunity to compare the ecological functioning of a largely intact forest ecosystem with the significantly modified ecosystems that typify the Earth’s temperate zone. A broader understanding of the conservation challenges and opportunities that scientists, managers, and conservationists face in this region should be of interest and value to practitioners seeking to balance economic sustainability with conservation and ecosystem integrity across the globe.

FIGURE 1.01. The coastal North Pacific rainforest (shaded area on map) extends from Yakutat Bay in southeast Alaska to Cape Caution along the central coast of British Columbia.

COASTAL TEMPERATE RAINFORESTS ARE OF GLOBAL IMPORTANCE

In contrast to the more famous and intensely studied tropical rainforests, coastal temperate rainforests have never been widespread globally. They constitute only 2% to 3% of the area of the world’s temperate forests. Coastal temperate rainforests are confined to a handful of relatively small areas, primarily on the northern Pacific coast of North America and the coasts of southern Chile and Argentina, Japan and Korea, and Tasmania and New Zealand (Alaback 1995; Schoonmaker et al. 1997; DellaSala, Alaback, et al. 2011). Although temperate rainforests once occurred in northwestern Europe, most have been eliminated or dramatically altered by millennia of high-intensity human occupation. Approximately half of the world’s coastal temperate rainforest is located on the northwestern maritime margin of North America (Ecotrust et al. 1995). DellaSala (2011) inventoried and described the world’s relatively rare temperate and boreal rainforests and provided a scientific catalyst for global and regional conservation.

Humans did not occupy the cool, coastal temperate rainforests of the Americas until less than 30,000 years ago. These ecosystems were largely unsuitable for agriculture, so people only lightly modified them after their arrival. However, the coastal temperate rainforest of North America south of Cape Caution on the British Columbia (BC) coast has been extensively modified by recent human activities, particularly clear-cut logging and road construction, sometimes followed by agricultural or urban development. Although most of the forests logged in this area have been regenerated to younger forests, these younger forests differ strikingly from the original forests they replaced (Alaback et al., this volume, chapter 4; Person and Brinkman, this volume, chapter 6). Fortunately, large amounts of the northern half of this forest are similar to what they were when people arrived in the region about 10,000 years ago, following the Wisconsin glacial period.

This area thus offers unusual opportunities for understanding recent ecological changes and learning how to develop and apply methods to sustain the ecological processes that yield the goods and services provided by those ecosystems. In addition, rich opportunities exist to restore the natural composition, structure, and functioning of portions of these forests that have been clear-cut and managed as even-aged timber plantations.

Ecological research on the temperate rainforests of the northern Pacific coast of North America has greatly increased both scientific and societal appreciation of the unusual features and complexity of the region’s natural forest ecosystems, especially its older forests (Franklin et al. 1981). Extensive and important faunal studies, particularly of flagship species such as the northern spotted owl, marbled murrelet, and Sitka black-tailed deer, were coupled with ecosystem-level research. The degree to which traditional forest practices, which created highly simplified systems in pursuit of efficient wood production, have reduced other forest values has been made clear by other scientific studies (Puettmann et al. 2009). The importance of managed lands (the semi-natural matrix) and limitations of protected areas as the only focus in conserving biodiversity and critical ecosystem processes has also become apparent (Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002; Franklin and Lindenmayer 2009).

Judged on taxonomic uniqueness, unusual ecological or evolutionary phenomena, and global rarity, coastal temperate rainforests are globally important ecoregions of the world (Olson and Dinerstein 1998; DellaSala 2011). The lowland, productive sites are among the terrestrial ecosystems with the greatest standing biomass. Hence, they may have a significant potential role in future carbon sequestration strategies (Fitzgerald et al. 2011). Even though the forests are dominated by a small number of tree species, the trees tend to be large, with multiple canopy layers. An abundant growth of shrubs, herbs, and cryptogams characterizes the understory. The biological richness of the forests resides in the forest canopies (arthropods and lichens) and the soils (rich animal and microbial communities).

Coastal temperate rainforests are found in regions that have undergone extensive climate changes over recent millennia; some were ice covered during the most recent glacial advances. They are expected to experience significant climatic changes in the near future as well. The coastal temperate rainforests of North and South America contain hundreds to thousands of islands, some of which were connected to the mainland in the recent past. They are still being colonized by new species in response to climate change and are not currently in species richness equilibrium (Cook and MacDonald, this volume, chapter 2). Because these forests occur in regions with high rainfall and complex topography, the interactions between their terrestrial and marine components are especially complex and important (Gende et al. 2002; Edwards et al., this volume, chapter 3).

THE RISE OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES

Life on Earth has survived repeated dramatic changes generated by physical forces and by life itself. The productivity and richness of Earth’s biota expanded and contracted over the nearly four-billion-year course of life’s evolution, but the general trend has been an increase in biological diversity. Humans have caused extinctions of species for thousands of years. When people first crossed the Bering Land Bridge to North America about 20,000 years ago, they exterminated—possibly by overhunting—many species of a rich fauna of large mammals (Ripple and van Valkenburgh 2010). Extermination of large animals also followed the human colonization of Australia. At that time, about 40,000 years ago, Australia had 13 genera of marsupials larger than 50 kg, a genus of gigantic lizards, and a genus of heavy, flightless birds. All of the species in 13 of those 15 genera became extinct. When Polynesian people settled in Hawaii about 2,000 years ago, they exterminated at least 39 species of endemic land birds. More recently European colonists caused the extinction of the Labrador duck (Comptorhynchus labradorius), great auk (Pinguinus empennis), Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), and passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), the most abundant land bird in North America when they arrived.

Although a long-term historical perspective might suggest complacency about current human-caused changes, today the major environmental changes are being caused by a single species. We are becoming acutely aware that our efforts to maximize the delivery of a few of the many goods and services potentially provided by ecosystems (e.g., timber, minerals, food) has greatly diminished their ability to supply many other goods and services (e.g., biodiversity conservation, flood control, water quality) (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2003).

Efforts to protect Earth’s rich array of habitats and ecological communities and to conserve species have a long history. Early conservation efforts concentrated on species of special economic or social importance, but gradually, as people became aware of the manifold consequences of the activities of Earth’s dramatically increasing human population, the scope of their research broadened to include habitat destruction and fragmentation, environmental contamination, spread of diseases, and loss of biodiversity. As Earth’s human population has grown rapidly and individual wealth has increased substantially in some nations, pressures to extract goods and services from ecosystems have dramatically increased.

At the same time, we recognize that people have lived in North Pacific temperate rainforests for a long time—since at least the last glacial retreat—and continue to live here today. Our aboriginal peoples—generally referred to as First Nations in British Columbia and Alaska Natives in Alaska—have always had a close relationship with the landscapes they inhabit. But nonaboriginal residents of this region are also more closely tied to their environments than most other North Americans, whether for hunting and fishing, employment in resource industries, or just generally enjoying their magnificent surroundings. Healthy human communities in the North Pacific temperate rainforest depend on vibrant ecosystems.

Two developing fields of scientific inquiry—conservation biology and island biogeography—are particularly relevant to efforts to understand and manage North America’s coastal temperate rainforests.

Conservation Biology

The rapid development of the discipline of conservation biology is a response of the scientific community and resource professionals to the accelerating loss of biodiversity. Its practitioners apply principles, data, and concepts from ecology, biogeography, population genetics, economics, sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy, in an effort to greatly reduce the current high rates of extinction of species. As the field developed, conservation biologists came to realize that concentrating their efforts on small areas and individual species, although it has conserved local habitats and ecosystems, has failed to stem the loss of Earth’s biological diversity. They recognized that they needed to plan and execute conservation strategies at greater spatial and temporal scales, that is, the scales at which the ecological and evolutionary processes that generate and maintain biological diversity operate (Olson and Dinerstein 1998). Conservation biologists have also recognized that management interventions, in addition to creating reserves, need to incorporate biodiversity concerns in the semi-natural landscapes that are being managed for commodity production (Lindenmayer and Franklin 2002).

These insights led to the recognition that large terrestrial areas, characterized by a distinctive climate and dominant vegetation, would be appropriate management units. They need to be large enough to potentially maintain viable populations of the species with the largest spatial requirements, large enough to enable the ecological and evolutionary processes that generate and maintain new species to continue, and extensive enough to include the great variety of Earth’s habitats and ecological communities.

Driven in part by the increasing fragmentation of mainland habitats and the extinctions that it may be contributing to, ecologists and conservation biologists are devoting much attention to extrapolating their research insights to large spatial and long temporal scales. What processes become most important at different spatial scales? Are different scales nested hierarchically? Which species have the largest area requirements for long-term persistence of their populations? What new concepts must be developed for the emerging field of landscape ecology?

Island Biogeography

Archipelagoes have long played a key role in helping scientists to recognize the importance of long temporal scales and large spatial scales for the evolution of life and for the structure and functioning of Earth’s ecosystems. Insights from the field of island biogeography, which began with the pioneering work of Alfred Russel Wallace (1869, 1876, 1880), help us understand the role of the history of physical changes and movements of organisms across the landscape in generating the current biota of coastal North Pacific temperate rainforests (Cook and MacDonald, this volume, chapter 2).

For more than 100 years, biogeography was primarily a descriptive field, but during the 1960s three major advances changed it into the dynamic multidisciplinary field it is today (Brooks 2004). The first was the publication of the equilibrium theory of island biogeography by Robert MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson (1967). The second, acceptance of the theory of continental drift, provided ways to explain many otherwise puzzling patterns in the distribution of organisms. The third, the development of phylogenetic systematics (Hennig 1966), provided the first phylogenies that were rigorously based on quantitative analyses.

Recognition that patches of habitat types on continents resemble islands in many respects stimulated the use of concepts of island biogeography to explore the dynamics of species on mainland “virtual islands.” One result has been the development of hypotheses of nonequilibrium island biogeography, the investigation of patterns of faunal relaxation on recently isolated habitats. Low mammal species richness in montane habitats in the Great Basin of North America (Brown 1971) and in the tropical rainforests of northern Queensland, Australia (Moritz 2005), are prime examples of nonequilibrium island biogeographic patterns.

As a consequence of dramatic sea level changes that accompanied the expansion and contraction of Pleistocene glaciers, many areas of the coastal temperate rainforests of North America that were formerly connected to the mainland have recently become islands. Studies of organisms on some of those islands, in Barkley Sound, on the west coast of Vancouver Island (Cody 2006), for example, have yielded important insights into floral relaxation. The biota of the coastal rainforests of North America is definitely not currently in equilibrium.

MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES OF THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

One of the primary challenges facing residents of coastal North Pacific temperate rainforests as we enter the twenty-first century is how to redesign our land allocation and management strategies to address the goals of maintaining vibrant and dynamic ecosystems and healthy human communities. There are numerous examples around the world (and farther south on our coast) where the ability of ecosystems to sustainably provide the full array of goods and services has been seriously compromised by resource development. Because of the largely undeveloped nature of North Pacific coastal landscapes—an increasingly rare commodity globally—we have an opportunity to work diligently to better understand the complex interrelationships among the different types of goods and services these ecosystems provide so that we can obtain some valuable resources (e.g., forest products) without diminishing other services (e.g., water quality, biodiversity).

To achieve these goals, it would be helpful to focus on ecosystems and not on political boundaries. The ecosystems and species in our region don’t recognize the BC–Alaska international border. Yet almost every inventory and mapping effort, and every management plan, has that border as its southern boundary (for Alaskan plans) or its northern boundary (for BC plans). There is little coordination in things like protected areas planning between BC and Alaska. If we want to properly protect this area, there must be.

Another border that needs bridging is the one between terrestrial, freshwater, and marine realms. There are few places on earth where marine and terrestrial realms are so closely linked as in coastal temperate rainforests. Yet terrestrial and marine managers generally work for different agencies and conduct their research, inventory, and planning in isolation from each other. Although this book is primarily about managing terrestrial and freshwater realms, many of the ideas and recommendations it contains must be implemented in cooperation with marine scientists and managers.

On the Canadian side of the border, almost all (>95%) of the land is Provincial Crown land (owned by the province). (Land claims negotiations currently underway with a number of coastal First Nations will likely result in considerable amounts of this land being transferred to First Nations ownership.) Land use plans were developed for BC’s central and northern coast in 2006, and in Haida Gwaii in 2010. These plans designate approximately one-third of the central and northern BC coast, and one-half of Haida Gwaii, as protected areas and set out management practices for the rest of the landscape.

In southeast Alaska, about 90% of the land area is federal land. The Tongass National Forest—at 6.8 million ha—encompasses nearly 80% of the land area; Glacier Bay National Park covers 12% of the region. The rest of the land base is managed primarily by the state of Alaska and private land holders including Native corporations. The Tongass Land and Resource Management Plan (USDA Forest Service 2008a) is the guiding document for most of the lands of southeast Alaska.

The objectives, profession, and practice of forestry, the most important modifiers of North America’s coastal temperate rainforests, have undergone major changes during the last 30 years as a consequence of fundamental changes in societal perc...