![]()

1

Native American Architecture on Puget Sound

WAYNE SUTTLES

It is not known how long the Coast Salish tribes of the Puget Sound region have been here nor by what route they came. The Northwest Coast was settled at least nine thousand years ago, and by four thousand years ago, its peoples were developing the economic and technological basis of Northwest Coast culture. The ancestors of the Coast Salish probably participated in this development. Until the mid-nineteenth century, they lived, as they no doubt had for millennia, in villages of one or more plank houses built along a shore or riverbank. Each house was the home base of a group of families who went out to different sites for fishing, hunting, and gathering, returned with foods they had collected, and spent the winter ceremonial season together. The plank house was dwelling, food-processing plant and storage facility, and theater.

The most common type was the shed-roof house, consisting of a permanent frame and removable roof and wall planks, all made of western red cedar. For the frame, slablike posts were set into the ground in pairs of unequal height, forming two rows parallel to the shore; the taller, on the side nearest the water, was the front of the house. The number of pairs determined the length of the house, the distance between them the width, and the difference in height the pitch of the roof, which generally was not great. The pairs of posts supported crossbeams, which supported purlins on which the roof planks were laid. These had lipped edges and interlocked like tiles. The walls were separate from the frame that held the roof and were made of wider, flat wall planks slung horizontally between pairs of vertical poles bound by cedar-withe ropes. The tops of the walls were secured to the ends of the roof planks, with the outer set of poles extending upward beyond the roof. Some houses had doors in front; others had doors at the ends.

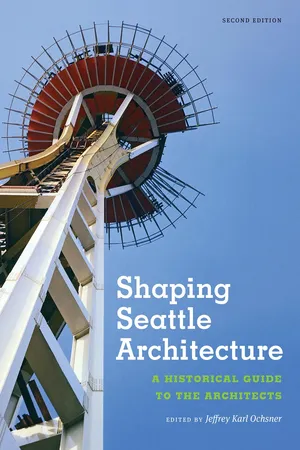

1. Model of wall construction, photographed on the Lummi Indian Reservation, ca. 1930. The wall boards are small and rough, but the method of attachment is authentic. This was one of several displays illustrating former practices. (University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections; photo by Eugene H. Field; NA 1818.)

Inside, the walls were lined with mats of cattail or tule rushes. Floors were bare earth, usually at the level of the ground outside but sometimes excavated. Sleeping platforms were built out from the walls, and storage shelves hung over them. In a smaller house, a section between adjacent pairs of posts was occupied by one family with its fire in the center; in a wider house, this space could be occupied by two families, one on each side. Sections were often separated by low partitions. Posts might be painted or carved with symbols of the vision powers of their owners. For ceremonies, people removed partitions, consolidated fires in the center, and provided a new smokehole by raising a roof plank. Often the frame belonged to a wealthy leader who had mobilized the labor to erect it, while the planks and mats of each section of the house belonged to the family who occupied it.

2. “Ruins of the old potlatch house of Chief Chow-its-hoot,” Lummi Indian Reservation, probably 1905. Although its length was estimated at 252 feet, Edmond S. Meany noted that this may have been longer before it was abandoned. (University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections; photo by Edmond S. Meany; NA 1237.)

The planks, split from a cedar tree trunk with wedges and carefully worked with a stone- or shell-bladed adz and dogfish-skin sandpaper, were especially valuable. The largest were three to four feet wide and more than twenty feet long. People often removed some when the house was unoccupied and laid them across pairs of canoes to make catamarans for transporting goods to and from other sites. At some sites, there were permanent frames that people covered temporarily with planks as in the winter village; at others, they simply erected frames of poles and leaned planks against them or laid mats over them.

The shed-roof house could be shortened by eliminating sections or extended by adding as many as the terrain allowed. Some were huge. The frame of Old Man House, still standing on Agate Pass in 1855, measured 520 feet long, 60 feet wide, 15 feet high in front and 10 in back. This house was reportedly built around 1815 by a Suquamish leader, the brother of Seattle. Clallam and Skagit leaders had similar houses. Perhaps around 1850, the Lummi leader Chowitsoot built a house, the frame of which was partly standing in 1905, that consisted of pairs of posts set about 24 feet apart, the front posts 12 feet high and the rear 9, holding crossbeams 40 feet long and 18 inches thick at their larger ends. Edmond S. Meany estimated the length of the house as 252 feet, saying that it could have been longer, as additional posts and beams could have by then disappeared. The rear posts bore a carved symbol of one of Chowitsoot’s vision powers—the sun carrying two bags of wealth.

Larger structures have been called “potlatch houses,” because they were built for the potlatch, a display of wealth and generosity, but they were also lived in. Exploring the Fraser River in 1808, Simon Fraser saw a Coast Salish village of about two hundred people all in one shed-roof house 640 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 18 feet high at the front.

Two other types of plank houses were built in this region. The gable-roof house had a central frame consisting of pairs of posts of equal height that supported crossbeams with king posts holding a ridgepole. Rafters rested on the ridgepole, the beams, and a set of wall posts standing well outside the central frame. The roof was like that of the shed-roof house, but wall planks were sometimes set vertically into the ground. The gambrel-roof house seems to have consisted of a central frame holding a nearly flat roof plus a lean-to on each side.

3. Gambrel-roof house on Penn Cove, Whidbey island, ca. 1890–1905. The posts and beam at the left of the structure, which appear to match those supporting its roof, suggest that this was originally part of a longer shed-roof house, rebuilt with nailed shakes and timber in order to expand its interior. The three smokestacks thrust through the roof were probably for cookstoves, and the tents, mats, and planks around the structure suggest that people had gathered for a potlatch. (University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections; photographer unknown; NA 826.) (A later view of this house, NA 694, is in Nabokov and Easton, Native American Architecture [1989], 238 [see appendix 1].)

From the mid-nineteenth century onward, the Coast Salish began building gable-roof houses with frames of posts and beams in the old style, but with roofs and walls of shakes and milled lumber nailed to the frame, known as smokehouses. By 1900, these were being abandoned as residences in favor of single-family houses like those of Euro-American settlers, but some of these “smokehouses” continued to be used for winter dances. Since the resurgence of winter dances in the 1950s, a number of Native communities have built new longhouses in modified versions of the late nineteenth-century dwelling

4. “Old potlatch house on Swinomish Reservation,” ca. 1905. This was probably a late nineteenth-century dwelling used for the winter dance. (University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections; photo by Edmond S. Meany; NA 1229.)

There are very few illustrations of the older house types used on Puget Sound. The best of the shed-roof houses are from adjacent regions to the north and west where this type was used—sketches made by Paul Kanes at Victoria in 1847 and early photographs taken on Vancouver Island and around Neah Bay.

Other house types were used elsewhere on the Northwest Coast. To the south, the usual type was a gable-roof house with central posts supporting the ridgepole, roof planks running parallel to it, and vertical wall planks set into the ground. On the northern coast, it was gable-roof house with the wall planks carefully fitted into the frames and usually with a painted facade or a totem pole as a doorway. These were masterpieces of craftsmanship and artistry, but they could not be easily stripped of planks for seasonal moves or altered in length in response to changes in the number of occupants, and the largest were no bigger than one section of the biggest Coast Salish house.

![]()

2

Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart (Esther Pariseau)

CHERYL SJOBLOM

Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart, 1900. (Sisters of Providence Archives, Seattle; photo by Hofsteater, Portland, Oregon, April 1900, Mother Joseph Collection, SP13.A1.2a.)

In early Pacific Northwest history, Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart (1823–1902) is recognized as among the first to care for orphans and the aged and the first to establish a hospital. She also played a role as architect, for which she was later honored by the AIA and the West Coast Lumbermen’s Association.

The daughter of a French Canadian carriage maker, Esther Pariseau (Mother Joseph’s birth name) was born on April 16, 1823, in Saint-Elzéar, Quebec, Canada. She learned carpentry at an early age, and when she joined the Sisters of Providence in 1843, she brought her skills as a builder to the religious community.

In 1856, Sister Joseph and four other sisters were sent to Vancouver, Washington Territory, at the request of Bishop A. M. A. Blanchet, who sought to establish a religious community on the frontier that would provide for the social and religious needs of early settlers and Native peoples.

1. House of Providence (later Providence Academy), Vancouver, Washington, 1867–73 (with addition, 1891), Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart. The size of this structure reflects the expanding mission of the Sisters of Providence in the Pacific Northwest. Providence Academy still stands and has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1978. (Sisters of Providence Archives; photo 1963; 22.A2.40.)

Mother Joseph’s background in carpentry and building soon proved useful, as she was responsible for remodeling a small room for use by the sisters as a dormitory, refectory, classroom, and community room; however, her skills were soon applied to larger projects. Her first new building was a cabin large enough for four beds, four tables, and four chairs. In 1858, this became Saint Joseph Hospital (destroyed), the religious community’s first hospital in the Pacific Northwest.

2. Saint Vincent Hospital, Portland, Oregon, 1874–75 (destroyed), Mother Joseph of the Sacred Heart (later additions by Warren H. Williams, architect). This first Saint Vincent Hospital was located at Twelfth and Marshall Streets until 1895. It was one of the first two hospitals in Oregon; the other, constructed almost simultaneously, was Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland, designed by Warren Williams. (Sisters of Providence Archives; photo ca. 1875; 53.A1.1.)

Tradition credits Mother Joseph with designing and supervising construction of an extensive network of facilities across the Pacific Northwest while at the same time continuing to direct the increasingly widespread activities of the Sisters of Providence. Thus, for example, she is credited with the design and construction of the House of Providence, later Providence Academy, Vancouver (1867–73; enlarged 1891). She is also known to have been involved in the design of several orphanages, hospitals, and schools in the region.

In the absence of clear records, however, the full extent of Mother Joseph’s role as architect and builder remains uncertain. As the Sisters of Providence developed a far-reaching network of facilities, Mother Joseph did work with local architectural professionals on at least some projects. For example, the Saint Vincent Hospital, Portland, Oregon (1874–75; destroyed), is generally credited to her, and records in the Archives of the Sisters of Providence written in 1892 describe the building as “the masterpiece of Mother Joseph’s architectural skill.” But when additions to this building were constructed in 1880 and 1882, local newspaper accounts identified Warren H. Williams as the architect of record. Whether Williams had any earlier involvement remains unknown. At Saint Mary Hospital (1879–80; later Saint Vincent Academy; destroyed) in Walla Walla, Washington, Mother Joseph was described as the “director and superintendent of the building” during the laying of the cornerstone on July 30, 1979, while O. F. Wegener, a local architect and civil engineer, was identified as the architect of record. When a large building was later planned in 1883 to replace the original building, the local arch...