![]() Part I / Introduction and Background

Part I / Introduction and Background![]()

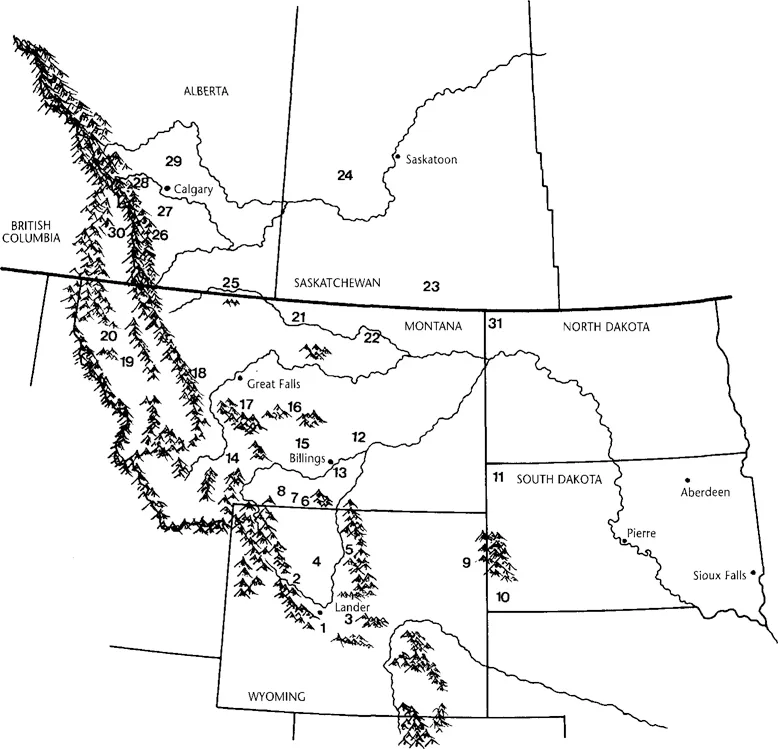

Map 1.1. The Northwestern Plains: Major Rock Art Sites

1. Little Popo Agie River

2. Dinwoody Lakes

3. Castle Gardens

4. Legend Rock

5. Medicine Lodge Creek

6. Petroglyph Canyon

7. Valley of the Shields

8. Joliet

9. Whoopup Canyon

10. Red Canyon (Southern Black Hills)

11. North Cave Hills

12. Castle Butte

13. Pictograph Cave

14. Missouri Headwaters

15. Musselshell River

16. Judith River

17. Smith River

18. Gibson Dam (Sun River)

19. Flathead Lake

20. Kila

21. Wahkpa Chu’gn

22. Sleeping Buffalo

23. Sf. Victor

24. Herschel

25. Writing-on-Stone (and Verdigris Coulee)

26. Zephyr Creek

27. Okotoks Erratic

28. Grotto Canyon

29. Crossfield Coulee

30. Columbia Lake

31. Writing Rock

1 / Introduction to Rock Art

For thousands of years, Northwestern Plains Indians carved and painted images on cliffs, rock outcrops, and boulders throughout the region—images with which Native people recorded their visions and chronicled their history. Often found in the spectacular settings of these peoples’ most sacred places, rock carvings and paintings represent the intimate connection between Native people and their spirit world. These images are a remarkable artistic accomplishment and a lasting cultural legacy of the Plains Indians. More than 1200 rock art sites have been recorded across the plains of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Montana, Wyoming, and the Dakotas (Map 1.1), and the images at these sites span the last 5000 years, with some possibly dating to the end of the Ice Age (ca. 10,000 B.C.). An expression of the spiritual and social lives of these ancient artists, rock art offers a fascinating glimpse into Native culture and history from the earliest occupation of the New World to the early 1900s.

Northwestern Plains rock art has captured the interest of Euro-Americans from the time of the earliest explorers in the region, which attests to both its abundance and its artistic beauty. Lewis and Clark provided the first written record of this art, but many other explorers, soldiers, traders, artists, and missionaries sketched rock art sites and collected examples of robe and ledger drawings. Early anthropologists also recorded sites and obtained information about the more recent designs from knowledgeable tribal elders (Wissler 1912, 1913; Mallery 1893). These early studies have proved invaluable for studying several rock art traditions, but most sites predate the occupation of this region by historically known groups; thus, much of the rock art is known only from its archaeological context.

The numerous articles and scientific monographs about Plains sites and styles, most written since the 1960s, form the most diverse body of rock art literature for any region of North America. Some works are broadly based syntheses of known data (Renaud 1936; Conner and Conner 1971; Wellmann 1979a; Keyser 1990), but even the most recent of these studies omits the four least-known rock art traditions and relies on incomplete data for three others. In the 1990s alone, hundreds of new sites have been described and interpreted in dozens of new publications. While researching this book, we consulted more than 200 written sources ranging from Ph.D. dissertations to single-site summaries written by local amateur researchers; we incorporated additional information from almost 100 other sites that have yet to be described in the literature (Map 1.2).

Despite this richly documented record, the public remains relatively unaware of and uninformed about much Northwestern Plains rock art. A few famous sites are visited by thousands of tourists each year, but information at these sites can vary greatly in quality and accuracy; sometimes it even suggests that rock art is a complete mystery. All too often the public receives the impression that this art’s origin and meaning are lost, and any interpretation of these images is therefore purely speculative. Inaccurate statements by professional researchers concerning its chronology (cf. Grant 1983:49) also lead to false impressions of the antiquity and significance of these images. Some sites have even been subjected to absurd “interpretation”: the work of Pre-Columbian Chinese cartographers, Celtic scribes, or Spanish bankers recording their transactions.

Map 1.2. The Northwestern Plains: Locations of Major Rock Art Study Projects

Boxed numbers indicate regional studies

1. Conner 1962, Conner and Conner 1971

2. Over 1941, Sundstrom 1993

3. Sundstrom 1984, 1990

4. Renaud 1936

5. Keyser 1992, Keyser and Knight 1976

6. Dewdney 1963

7. Brink 1981, Klassen 1994a

8. Greer 1995

9. Corner 1968

10. Secrist 1960

11. Dewdney 1964, Keyser 1977a, Brink 1979, Magne and Klassen 1991, Klassen 1995

12. Leechman, Hess, and Fowler 1958

13. Jasmann 1962

14. Sowers 1939, 1940

15. Gebhard 1969

16. Gebhard and Cahn 1951

17. Gebhard 1954, Walker 1992

18. Tipps and Schroedl 1985

19. Mulloy 1956

20. Conner 1980

21. Conner 1984, 1989a

22. Fredlund 1993

23. Keyser 1979a

24. Johnson 1976

25. Jones and Jones 1982

26. Conner 1989b

27. Loendorf 1984, Loendorf and Porsche 1985, Loendorf et al. 1990

28. Loendorf 1990

29. Loendorf and Porsche 1987

30. Walker and Francis 1989, Francis et al. 1993, Francis 1994

31. Gebhard et al. 1987, Renaud 1963, Sowers 1941, 1964

32. Tratebas 1993

33. Schuster 1987

34. Sundstrom 1987, 1989

35. Greer and Greer 1994a, 1995a, 1996

36. Wintemberg 1939

37. Keyser 1984, 1987

38. Buckles 1964

39. Shumate 1960

40. Keyser 1978; Brink 1980

Rock art sites in fact chronicle the long histories, the hunting ceremonies, and the religions of the region’s diverse Native peoples. They reveal their relationships with the spirit world and record their interactions with traditional enemies and the earliest Europeans, Americans, and Canadians who explored and later colonized the area. Although some rock art conveys only enigmatic messages from an unknown past, many sites can be dated or attributed to a specific group or culture. Some rock art can even be read almost like a simple sentence. Unfortunately, ignorance of this rich cultural record has led to thoughtless vandalism and the defacing of many sites with graffiti. At some sites petroglyphs and pictographs have been removed and stolen, or destroyed in the attempt. A few sites, like Ludlow Cave in South Dakota, have been entirely destroyed.

This book is intended to help interested persons learn about and appreciate the origins, diversity, significance, and beauty of Northwestern Plains rock art. We hope first to provide the reader with a general overview of this art, and further, that this effort will lead to increased public appreciation and concern for this treasure from the past.

Petroglyphs and Pictographs

Rock art includes both engravings, or petroglyphs, made by cutting into the rock surface, and paintings, or pictographs, made by coating the rock surface with pigment. A wide variety of techniques was used to make each type.

Incising and pecking were the most common methods for making Northwestern Plains petroglyphs. Incised petroglyphs were originally cut into the soft sandstones of the region by bone, antler, or stone flake tools to produce sharp, deep U-shaped or V-shaped grooves. After the introduction of metal to Plains cultures in the early postcontact era, knives and other sharp iron tools were also used to incise petroglyphs. Although most incised petroglyphs were probably drawn freehand, some nearly perfectly circular shields suggest that an aboriginal thong-and-pin compass was occasionally used. Sometimes a well-executed design is paired with a similar but coarse and uneven scratched or incised version, suggesting that a rough sketch may have been executed before the finished carving.

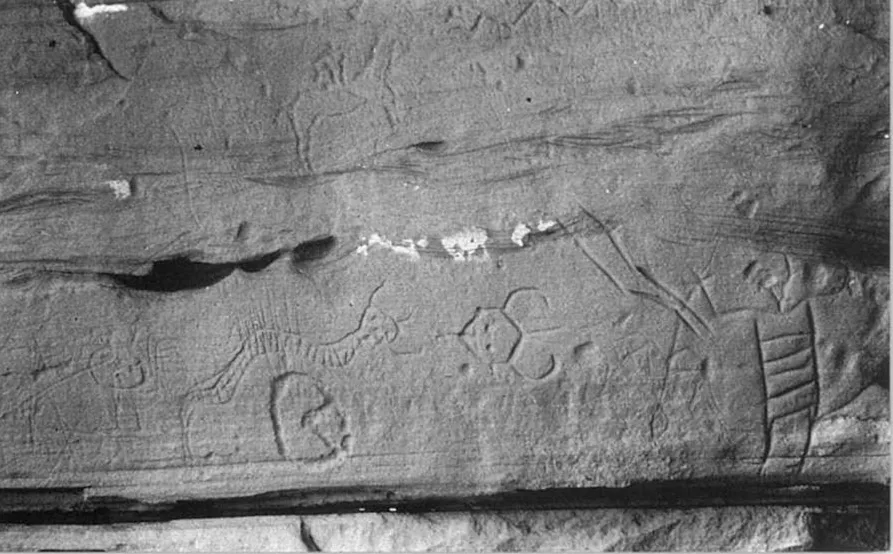

Pecked, incised, and scratched petroglyphs cover this panel in the North Cave Hills. The pecked horse and rider (top left center) and pecked horse hoofprint (bottom left center) are unusual.

Pecked petroglyphs were made by direct and indirect percussion. Direct percussion involves repeatedly striking the rock surface with a piece of harder stone to produce a shallow pit, which was then gradually enlarged to form a complete design. Indirect percussion, whereby a small chisel stone is positioned against the rock surface and then struck with a hammerstone, provides more accurate control of the pecking and was probably used to produce the more carefully made pecked designs. Pecking occurs throughout the region on harder sandstone surfaces and also on granite and quartzite glacial erratic boulders scattered across the Plains north of the Missouri River.

Scratched petroglyphs occur frequently on the Northwestern Plains. These were made by lightly incising the rock surface with a sharp stone or bone flake or metal tool. Unlike incised petroglyphs, which are carved by repeated strokes along the same line, most scratched petroglyphs were made with a single stroke. The freshly made scratches were highly visible to the artists, as the scored line contrasted sharply with the darker surface of the weathered rock. Weathering eventually renders many scratches nearly invisible except under optimum lighting conditions.

A few petroglyphs are abraded—rubbed into the naturally rough cliff surface with a harder stone to create an artificially smoothed and flattened area, which contrasts with the natural surface texture. Large pecked designs, such as hoofprints and oversized animals, were sometimes refined by abrading within their outline, but a few designs were formed solely by abrasion. Finally, a few designs at some sites were made by drilling into the sandstone surface small pits arranged in lines to form figures.

Petroglyph techniques are frequently combined on the same panel or even on the same figure. Often new petroglyphs in different techniques were added to a panel by different artists at a later time. In many instances, an artist used multiple techniques to make a single figure, but sometimes the original design was modified by a later artist using another technique. The most frequent multiple-technique petroglyphs are pecked figures with incised features such as eyes, mouth, heartline, fingers, legs, or horns/antlers. Many pecked designs also have abraded parts, and a few Historic period figures were first scratched and then abraded. Incising and scratching sometimes occur together deliberately, but a few very carefully incised figures have somewhat carelessly executed scratched features that appear to be later additions. One design at Writing-on-Stone is an incised human partially pecked out by a later artist.

Northwestern Plains pictographs are most often red, but yellow, orange, blue-green, black, and white pictographs are also known. Most pictographs were painted using a single color, and polychrome paintings are very rare. The most notable polychromes are the Great Turtle Shield and other shields at Castle Gardens, Wyoming, and painted shields in the Valley of the Shields, southern Montana.

Pictograph pigments were made from various minerals. Iron oxides (hematite and limonite), often found in clay deposits, yielded reds ranging from bright vermilion to dull reddish brown, and also yellow. Often called red and yellow ochre, these minerals were sometimes baked to intensify their color. Some orange pigments were made directly from powdered ironstone or other naturally occurring iron-rich rocks. Ash-rich clays and diatomaceous earth yielded white pigment, copper oxides produced blue-green colors, and charcoal made black pigments.

To make a pigment suitable for painting, the crushed mineral was mixed with water or an organic binding agent to form a paste or liquid. Ethnographic descriptions and archaeological work from other areas of North America document such binding agents as blood, eggs, animal fat, plant juice, or urine. As yet, little analysis of Northwestern Plains pigments has been undertaken to identify possible binding agents.

Most pigments were applied to the rock surface using fingers and brushes. Northwestern Plains pictographs are most often finger painted, as indicated by finger-width lines on many figures. Some paintings show fine lines of relatively evenly applied pigment that indicate the use of small brushes made from animal hair, feathers, porous bone fragments, or frayed twigs. Twig and bone brushes are well documented in the Plains ethnographic record. In some cases, both finger and brush painting were used on the same figure. Other designs show a characteristic waxy texture and somewhat spotty paint application, indicating that they were drawn with an ochre “crayon”—a lump of pigment with a greasy consistency, perhaps from being mixed with animal fat. Some black and reddish-orange designs were drawn with a piece of charcoal or a raw lump of ironstone, much like using chalk on a blackboard. These have a similarly spotty appearance, but lack the texture of “crayoned” drawings.

Handprints at sites along the Rocky Mountain front ranges in Alberta, Montana, and Wyoming were made by dipping the hand in paint and then pressing it against the rock surface. Paint was also spattered, smeared, and blown onto some sites to produce designs. Paint spatters or smears measuring several meters across are common at some central Montana and western Alberta sites. Blowing paint through a tube or spitting it directly from the mouth was used to make negative handprints at a few Wyoming sites and two Montana pictographs. To make such designs, the hand is held against the cliff, and paint is blown around it so that when it is lifted, an unpainted hand-shaped area remains.

The finger-width lines of the hoop and the blockbody human figure at Grass! Lakes, Alberta, are characteristic of finger-painted pictographs.

How pigments can survive on exposed cliff faces has long been the subject of scientific debate. Early scholars, presuming that pigments would fade rapidly, argued that all of these paintings were made during the last few hundred years. Some even reported that they would not last beyond a few more decades. We now know that most rock paintings are not rapidly disappearing. While there is evidence that some designs on sandstone cliffs are fading, some sandstone surfaces retain pictographs quite well. One site at Writing-on-Stone looks as vivid in a photograph taken today as it does in one taken in 1897. At a central Montana site, a painting of a shield-bearing warrior using an atlatl remains distinct and readily visible, even though it may be more than 1700 years old. Other paintings at two sites have been dated to between 800 and 900 years ago using scientific methods.

Research has demonstrated why these paintings are so durable (Taylor et al. 1974, 1975). When freshly applied, the pigment stains the rock surface and seeps into microscopic pores by capillary action. By this means, it becomes part of the rock. Mineral deposits coating many cliff surfaces further preserve these paintings. Rainwater, washing over the surface of the stone or seeping through microscopic cracks and pores, leaches naturally occurring minerals—calcium carbonate, aluminum silicate, or other water soluble minerals—out of the rock. As the water evaporates on the cliff surface, it precipitates the mineral as a thin, transparent film over the pigments. Microscopic thin-section studies show that staining, leaching, and precipitation have made the prehistoric pigment part of the rock surface, thus protecting it from rapid weathering and preserving it for hundreds of years. In areas with extensive water seepage, however, mineral deposits may eventually become so thick that they form an opaque, whitish film that obscures pictographs, which explains why some may eventually fade from view. In fact, at a few sites, prehistoric artists painted new designs over those more ancient ones partially obscured by precipitated minerals, and thus provided evidence of the relative ages for these designs.

Desc...