![]()

I

AN ARTISTIC AND LITERARY PORTFOLIO

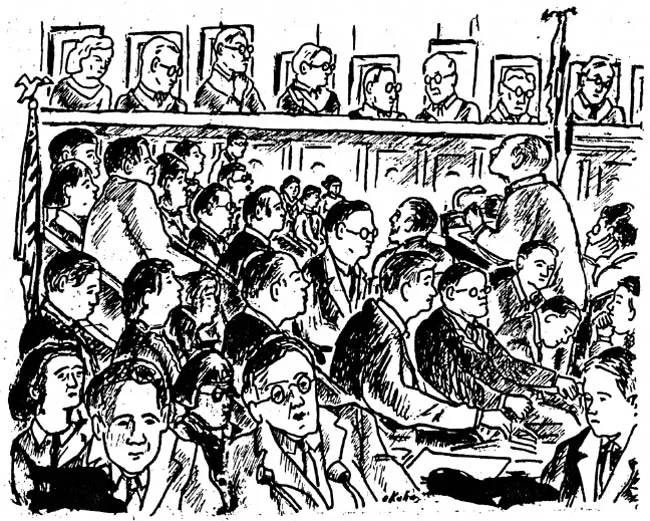

Miné Okubo, Drawing of Redress Cases before U.S. Supreme Court, 1987, pen and ink

Miné Okubo, Drawing of Redress Cases before U.S. Supreme Court, 1987, pen and ink

Miné Okubo, Girl and Cat, 1977, brush and ink

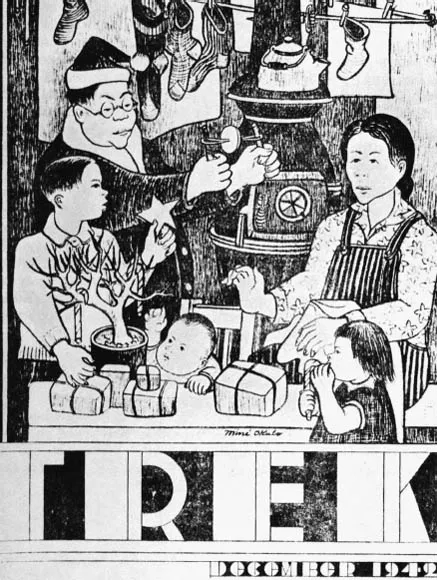

Miné Okubo, cover of Trek 1, no. 1 (December 1942)

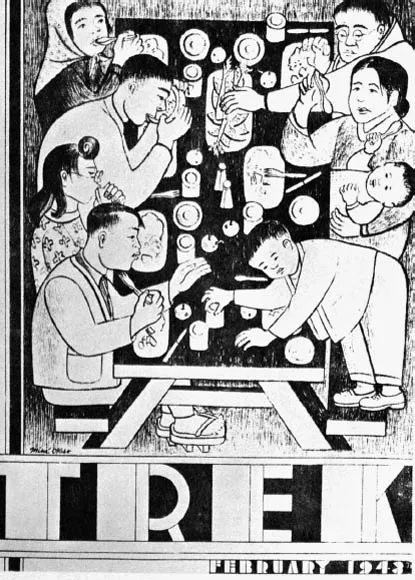

Miné Okubo, cover of Trek 1, no. 2 (February 1943)

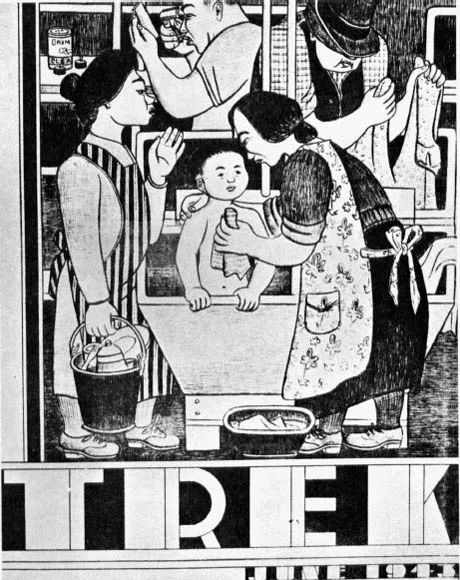

Miné Okubo, cover of Trek 1, no. 3 (June 1943)

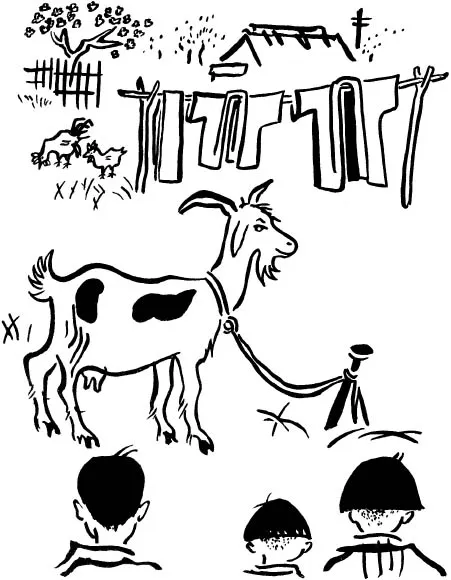

Miné Okubo, illustration for Where the Carp Banners Fly by Grace W. McGavran

Miné Okubo, illustration for Where the Carp Banners Fly by Grace W. McGavran

Miné Okubo, illustration for Where the Carp Banners Fly by Grace W. McGavran

Miné Okubo, illustration for Ten Against the Storm by Marianna Nugent Prichard

Miné Okubo, illustration for The Waiting People by Peggy Billings

Miné Okubo, illustration for The Seven Stars by Toru Matsumoto

Miné Okubo, Fish, 1942, oil on canvas

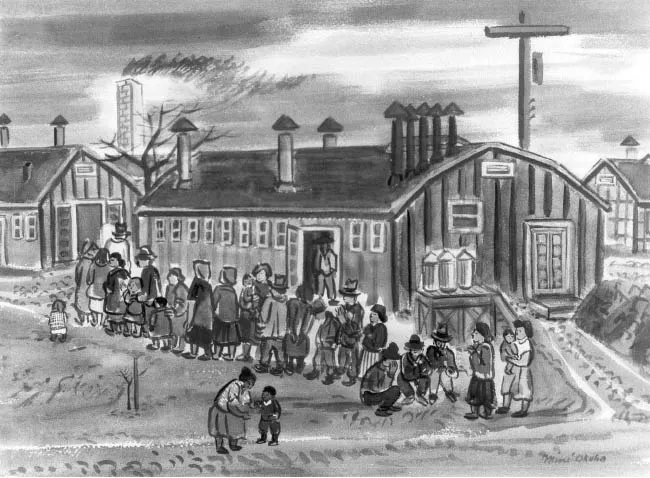

Miné Okubo, Men’s Hall Line-up, 1942, oil on canvas

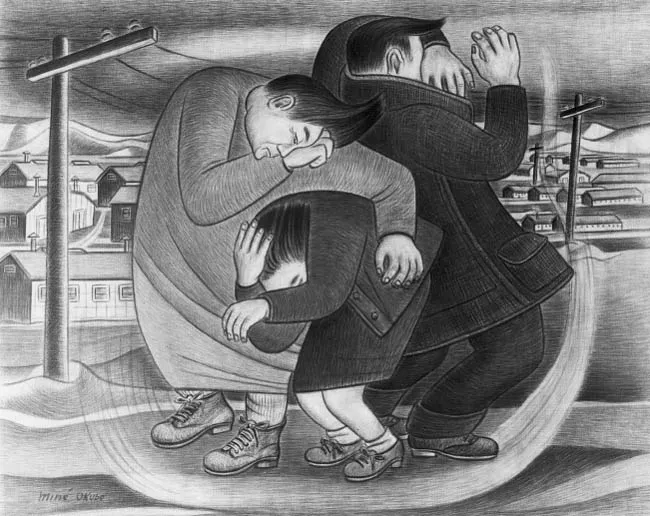

Miné Okubo, Dust Storm, 1942

Miné Okubo at a tea in her honor sponsored by the Common Council for American Unity, New York, March 6, 1945

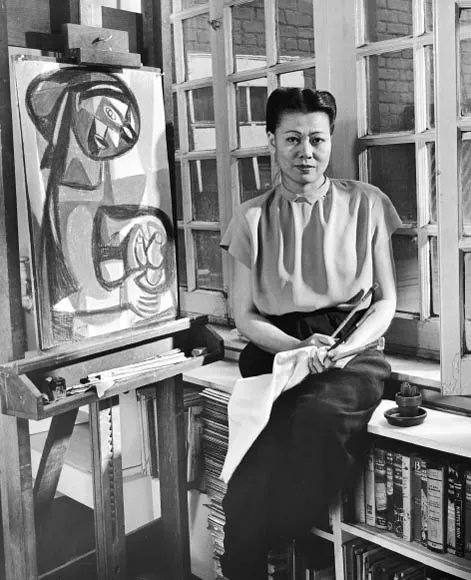

Clemens Kalischer, Miné Okubo, 1948

Clemens Kalischer, Miné Okubo, 1948

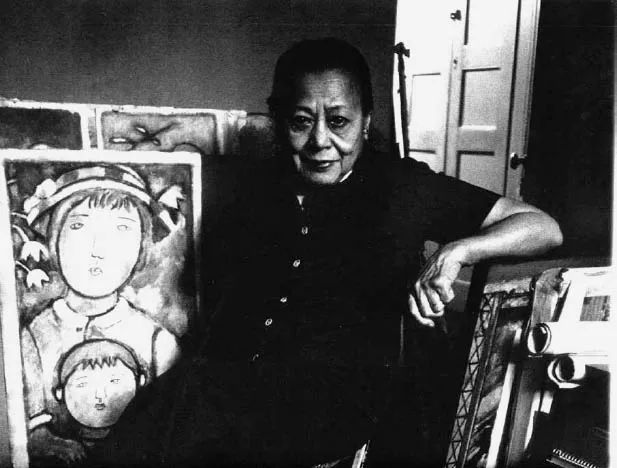

Clemens Kalischer, Miné Okubo, 1955

Masumi Hayashi, photo-collage of Miné Okubo, 1997

Irene Poon, photograph of Portrait of Miné Okubo, 1996

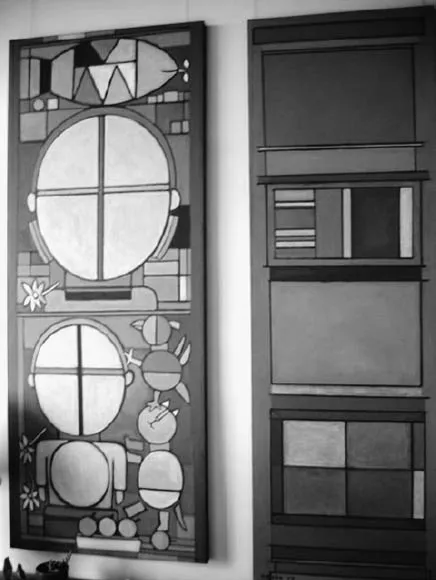

Miné Okubo, Untitled Abstract, oil on canvas

Miné Okubo, Girl, oil on canvas

Miné Okubo, Untitled Abstract, oil on canvas

![]()

1

RIVERSIDE

MINÉ OKUBO AND FAY CHIANG

In the last months of her life, from a hospital bed at New York University Medical Center and then Cabrini Nursing Home, Miné vividly recounted stories about her hometown Riverside: her childhood, her mother and father, her older brothers and sister, and how she was so very shy she hardly spoke, but watched with great curiosity the people and events around her.—FAY CHIANG

Oh, Papa and Mama worked so hard for us kids. Papa made candies in a store. At night he’d come home late from work and wake us up, the ice cream dripping. And Mama was always cleaning and cooking and sewing. I said to myself, I’m never going to get married and wash someone else’s socks. Forget it.

What a bunch we were. One autumn the leaves were falling to the ground and Papa and Mama told us, “Rake up those leaves.” Well, we kids shook those trees so the leaves would fall off, and the ones that didn’t, we climbed up the branches and pulled them off. That way we only had to rake the leaves once. When our parents saw what we had done, they said, “Ah! Bakatari! Bakatari!”

Another time we left our clothes hanging from the bedposts. Mama told us to put them away instead of leaving them all over the place. Well, we kids took care of that: we sawed off the bedposts!

We were a handful, but lively and imaginative.

When my brothers were older, every night when the weather was warm, we built a bonfire. Oh, my brothers were good looking! Girls falling all over them, even fighting one another for one of them! They were colorful, hair slicked back like Valentino and beautiful wide sashes tied around their waists.

Me? I was just a kid watching everything. It was very interesting. Riverside was filled with orchards then. Oh, that smell at night and the sky full of stars.

We had all kinds of people coming around: tramps, hobos, friends, and even criminals! Neighbors? Oh, we had everybody: a Mexican family, two other Japanese families, Irish, Italian, a school nearby for American Indians, and yes! Gypsies.

There was music and singing and dancing all through the night! And when we got hungry, the boys would go off and steal a couple of chickens, pick some ears of corn or whatever was growing at the time and cook it in the fire.

Papa and Mama? They were with all their kids.

Next door there was a house that was empty for the longest time. Whoever lived there before had planted a lot of fruit trees—apples, peach, lemons, pears. Since there was no one to pick the ripe fruit, we just ate it off the trees. Nah, we were never hungry. We loved to eat!

Did you ever eat a green apple with salt? My brother and I would climb into an apple tree with a salt shaker and just sit taking bites out of apples like squirrels.

Oh, it was the best childhood. I would lie in the grass staring at the sky and clouds, the blades of grass, and watch the ants on the ground. It’s all in nature. We can only simplify the Creator’s work.

I walked everywhere for miles by myself as a little kid, and sometimes, all the way to town where I would climb the highest building to look-see all around.

At school they didn’t know what to do with me, but they knew I had it in art from when I was little, from the very beginning, so the teachers left me pretty much alone.

When I went to Riverside Community College, I could hardly read or write. I kept asking questions, “How do you write that?” “What does that mean?” I had teachers, people who believed in me, helped me.

My mother was a renowned calligrapher. She came to America to represent Japan in the St. Louis Exposition, but look at what happened to her taking care of all those kids.

When I was traveling through Europe after graduating from Berkeley, I sent her a postcard every day telling her about my adventures. I came back when she was sick and she died shortly after. I found those postcards after she died. She had saved every one.

I want to be cremated. Scatter my ashes over Mama’s grave in Riverside. I planted an olive tree there for her a long time ago. Me? A lemon tree.

Like your mother.1 Oh, they put her in a nice spot on a hill. Next to a tall, tall tree and a flowering bush. Surrounded by her family. Your mother looked so young. But what you going to do?

No, I wasn’t going to get married to anyone. Cook his dinner, do laundry all the time. Look at you! I don’t know how you have so much laundry! (Miné often sat in the laundromat waiting for me to finish my family’s wash, so we could go to the movies together. She loved the movies.)

I only know how to do one thing: Art.

My sister—a tiny thing—is so capable. She could drive a car, even a tractor. She had a gallery in the Mission for about a year before she got married. She painted, worked on the chicken farm, had kids. I don’t know how she did it.

What are you waiting for? Do it while you’re young, while you can. Look at me. At the end. But I had a good life. I’ve done everything I wanted to do.

I like it here [the Cabrini Nursing Home]. It’s clean and people are so nice. Nah, I can’t eat all this stuff. All these visitors bring me so many cookies and fruit. How is one person supposed to eat all that food? You eat it!

I’m right next to the window. It’s quiet around here. At night I watch the airplanes and the bridge lights look so pretty, all lit up.

Who brought those flowers? I have so many visitors. You know they’re going to do a big show of my work at Riverside. The president of the college came to see me.2 Look it. They’re building a new gallery and they want me to open it. I guess they think I’m a big shot! Can you imagine, all my paintings.

Well, I got it now. I’m finishing up you see. My art is the mastery of drawing, color and craft staying with subject and reality, but simplifying like the primitives. It took all those years, but I got it.

What you think? I’d have to get on an airplane. You would come? We could bring the whole gang—Xian, your sister, Kathy, and the art store kids.3 I’ll see people I haven’t seen in a long time. Show them my paintings. It will be one big party with lots of food, people.

NOTES

This essay was read at Miné Okubo’s memorial services at Riverside Community College in Riverside, California, on March 18, 2001, and at the Japanese American United Church in New York City on April 7, 2001.

1Miné attended the wake and funeral of my mother, who passed away two years ago. Miné and my mother knew each other from encounters at art openings at the Basement Workshop where I worked, or from joining our family for Lunar New Year dinner, or from meeting up at the South Street Seaport or near Miné’s apartment in Washington Square Park. Whenever they met, they would run toward one another and say, “Oh! How young you look!” “How do you do it!” Watching my mother and Miné holding each other warmly by the elbows, I would just shake my head.

2President Salvatore G. Rotella and consultant Mary Curtin from Riverside Community College visited Miné in December 2000 at the nursing home and took her to lunch at a wonderful midtown Italian restaurant. It was Miné’s last trip outside.

3In 1990, when Xian was five and a half months, I brought her to meet Miné for the first time at her apartment. As Miné took out her latest paintings to show me, Xian sat Buddha-like, unblinking on Miné’s bed, staring at the paintings with their beautiful colors and shapes. Miné said, looking at Xian, “Now that one has a business head, no poor artist for her!” Miné was prophetic! We sat in the Washington Square Park children’s playground in the afternoons through the passing seasons, sipping coffee while Xian played in the sandbox with other children. Often we were joined by Teru Kanazawa and her two young sons, Mikio and Terence Sheehan. Teru’s father is the writer Tooru Kanazawa and a friend and contemporary of Miné’s during the war and in the years after the war in New York City.

![]()

2

AN ARTIST’S CREDO

A PERSONAL STATEMENT

MINÉ OKUBO

My interest from the beginning has been a concern for the humanities. Having traveled and studied people and art in Europe, experienced the commercial world of New York, and lived [through] the Japanese Evacuation, I decided to follow the individual road of dedication in art instead of the popular arts of the times. By using all my techn...