![]()

Elements of the Art

Color

In the use of color we find one of the great unifying characteristics of the art. The colors in painting were limited, before the opening of the trade with Europeans, to a few natural pigments. The conventions of the art were so strong, or the Indian artists so conservative, that the introduction of trade paints did not materially affect the selection and use of color. The principal colors were black, red, and green, blue, or blue-green. The black was generally derived from lignite, although graphite and charcoal were also used. Red, before the trade period, was derived from ochers, and several specimens of paint stone in the Washington State Museum have been identified as hematite. Mungo Martin, a Kwakiutl trained from youth as an artist, told me that it was his understanding that the Kwakiutl had “no good red, only brown like iron rust,” until the Hudson’s Bay Company introduced “China red in paper packages.” This would agree with Emmons’ statement in reference to Chilkat face painting: “The primitive colors were black, from powdered charcoal, and red, from pulverized ocher, but after the advent of Europeans, vermilion of commerce took the place of the duller mineral red” (Emmons, 1916:16–17). The “vermilion of commerce” is Chinese vermilion, which was packaged in paper envelopes. Native cinnabar may have furnished red pigment also, but the purity and richness of the vermilion coloring on a large proportion of Indian painted objects suggest the Chinese vermilion.

The greens and blue-greens were probably derived from copper minerals. Shotridge identifies a greenish-blue pigment used on an old helmet as “the covelline, a sulphide of copper” (Shotridge, 1929:339). Among the Bella Coola such extensive use was made of a medium cobalt blue that it might be considered characteristic of the painting of that tribe.

White was occasionally used, as well as yellow. Sometimes the whites of eyes, teeth, and small separating or relieving elements were painted white, and the Kwakiutl commonly used it as a ground color, especially since the last decade of the nineteenth century. The occurrence of white and yellow is, however, so limited in the two-dimensional art of the northern tribes that they can be considered unusual; black, red, and blue-green are therefore considered the standard colors in painting. In the Chilkat blanket and related woven objects the white of the wool (as the ground color) and a yellow derived from wolf moss (Evernia vulpina) are typical, along with blue-green and black.

19 Painting from a spruce root mat, Haida. Private collection.

20 Painted wooden spoon, Stikine Tlingit. Burke Museum catalogue number 2334.

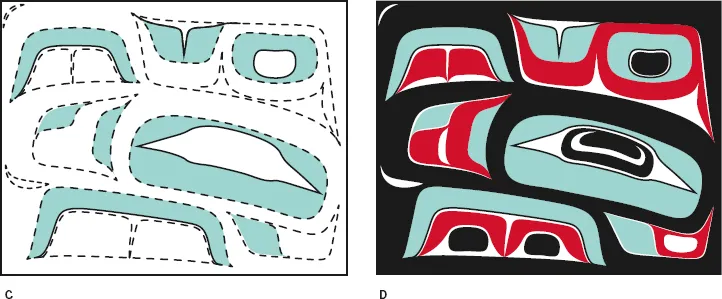

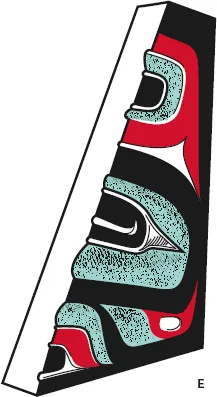

21 The three classes of design elements and their relation to color and surface. (A) The black primary formline pattern, forming a continuous grid of relatively even weight and complexity. Inner ovoids are always free-floating. (B) Red secondary elements and formline complexes. Inner ovoids enclosed by secondary ovoids are secondary, although always black. (C) Isolated blue-green tertiary elements filling much of the remaining space. True lines border many of them. (D) The three classes together. (E) Cross section showing relation of color to surface form, when carved. Primary and secondary designs are on the plane surface. Tertiary elements and ground are variously recessed, the former either blue-green or unpainted and the latter unpainted.

Painting was done with brushes of various sizes made of hair, often of the porcupine, inserted in a handle of wood. The bristles were fastened in a flat bundle cut off at an angle on the end. The brush was drawn toward the painter, edgeways for lines, flatways for filling in areas. Mungo Martin stated that the handle should be round and slim so that the painter could twirl it easily between thumb and forefinger in order to turn corners, in a manner suggesting the technique of a modern sign painter. The pigment was mixed with a medium prepared by chewing dried salmon eggs wrapped in cedar bark and spitting the saliva and egg oil mixture into the paint dish (Boas, 1909:403). Leechman (1932:37–42) attributes some paint properties to the cedar bark; the personal experience of the writer indicates that the use of cedar bark wrapping for the eggs serves primarily to retain the membranous parts and keep them out of the paint itself.

Emmons (1907:350) established that there was a standardized system for the placement of the several colors of a Chilkat blanket which guided the weaver, even though the pattern board used gave no intimation of their position, except for the black. The literature does not note that there was a similar system, if anything more rigid, which applied to two-dimensional painted art. This system is all the more interesting because it gives us a clue to the thinking of the Indian artist in terms of figure and ground. The color arrangement formula was followed with amazing consistency over the whole coast, even including the Kwakiutl, who were late-comers to the system.

Corresponding to the three standard colors are three classes of design elements. Black can be termed the primary color, and the elements painted black can ordinarily be called primary elements (Fig. 19). It is represented in the illustrations as ■.

Red is the color next in importance and will be termed the secondary color. Red elements will be called secondary elements. Red and black can be substituted for each other as primary and secondary elements under certain conditions. Of the painted pieces analyzed, 85 per cent used black for the primary design; 13 per cent used red as primary (Fig. 20); and the remaining 2 per cent used black in some areas and red in others. Red is represented in the illustrations as ■.

Blue-green occupies a special place in the system of color use and will be called the tertiary color ■.

Primary Color Use

The primary color, usually black, is used for the main formlines of the design (Fig. 21A). A formline is the characteristic swelling and diminishing linelike figure delineating design units. These formlines merge and divide to make a continuous flowing grid over the whole decorated area, establishing the principal forms of the design. One of the most striking features of the primary design is its continuity. In a typical piece all primary units are connected, with the exception of the inner ovoids of joints and eye designs. It is possible to begin tracing the primary forms at any point and to touch them all, with the exception noted, without a break. A few examples show breaks between large primary complexes, but only one of the examples recorded showed a real lack of continuity. A few other pieces show almost no primary continuity, but were so atypical in other respects that recording was impossible with the check list used (Barbeau, 1953:Fig. 185; Keithahn, 1962:19 and 1963:134).

There is another very important characteristic of the primary design. If the design is carved in low relief, the primary formlines are without exception on the plane surface of the carved material (Fig. 21E).

Secondary Color Use

The secondary color, usually red, is used in formlines of secondary importance to the design, for details, accents, and continuants of primary designs (Fig. 21B). Secondary designs are often enclosed by primary formlines and are always in contact with the adjacent primary units at one or more points. They may occur as isolated single units or as complexes, in which case they exhibit the same continuity to be found in primary design complexes. In every way except color they are like designs of the primary class. They may even enclose “subsecondary” design units of their own.

Red is the usual color for cheeks and tongues; arms, legs, hands, and feet are red in about half of the examples in which they occur. Red can be used as the primary color in all of the design. When it is used in primary elements, black takes its place for the secondary formlines.

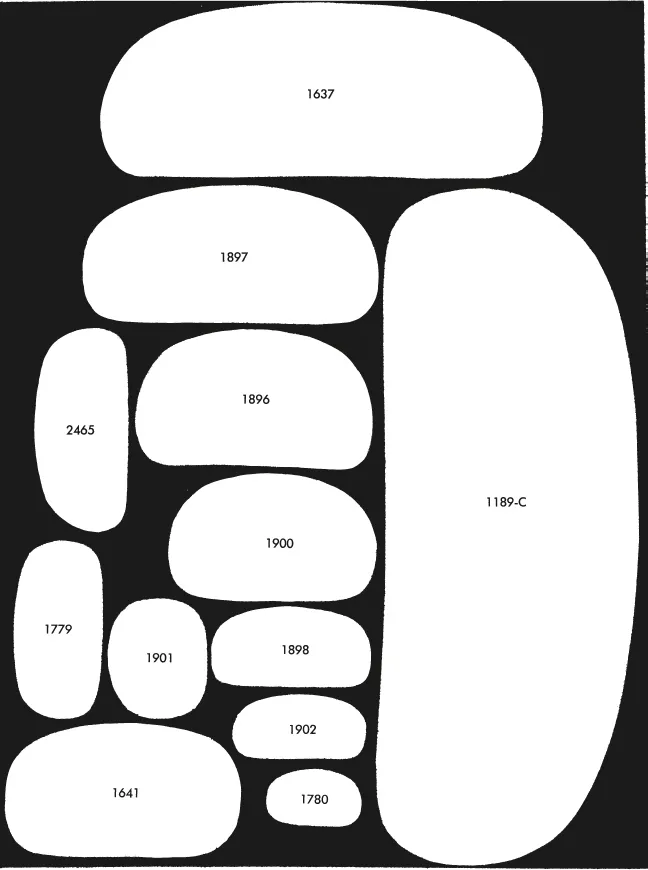

There seems to be only one primary element for which red is almost never used. That is the inner ovoid of an eye or joint design, which is almost always black. Of the 269 pieces showing color, 246 used black exclusively for this inner ovoid. Most of the others used black in some of the inner ovoids and red, blue, natural, or inlay of copper or abalone in others. Probably significant is the fact that of the eleven pieces using only red for the inner ovoid, eight were dishes of the type shown in Figure 52A, and four of those were documented as having been collected in the Haida village of Massett between 1887 and 1889. Another exception is in the case of the design appearing on a black ground, in which event the inner ovoid is red, as a primary element. An example of this usage is seen in appliqué blankets and dance shirts, which are typically dark blue with the design in red.