![]()

The Lower Columbia

THE LOWER COLUMBIA AREA of the Plateau consists of the river’s watershed between Priest Rapids and The Dalles, excluding the Snake River. In addition to the main channel of the Columbia River, with its multitude of rock art sites, the region includes the basins of the Yakima, John Day, and Deschutes rivers, in each of which rock art sites are plentiful. Geographically, the area is bounded by the Cascade Range on the west, the Yakima-Columbia divide to the north, the Snake River drainage to the east, and the northern Great Basin on the south.

Lower Columbia terrain is arid, forested only on the eastern flanks of the Cascades and atop low mountain ranges such as the Ochoco Mountains and Horse Heaven Hills. Major rivers provide most of the region’s water, serving to concentrate prehistoric occupation in villages along the Deschutes, Columbia, and Yakima. No large lakes, so typical of the northern Columbia Plateau, occur. The lower Yakima valley, below Selah Canyon, is a wide, flat, alluvial plain flanked by lofty arid ridges. The John Day and Deschutes rivers drain the high, dry, lava plateau of north-central Oregon, but are deeply entrenched in narrow canyons for most of their lower reaches. The lower Columbia River, which flows through a picturesque, basalt-rimmed gorge more than one thousand feet deep, is well known to most travelers through the area, thanks to Interstate 84 and the Columbia River Scenic Highway, which parallel the river on the Oregon and Washington sides.

As in the central Columbia Plateau, dams along this stretch of the Columbia River have drowned more than half of the known rock art. At least forty-five sites were completely or partially destroyed when The Dalles, John Day, and McNary dams were completed and their reservoirs filled between 1955 and 1968, and it is likely that other, smaller sites were obliterated before they were found and recorded. Despite this wholesale destruction, we have reasonably good records of most sites, due to early scientific interest in the area and the efforts of dedicated amateur researchers who photographed and made rubbings or tracings of many designs before they were lost. In addition, parts of a few sites were salvaged and are now on public display in several places.

Although Lewis and Clark, traversing this terrain in 1805–1806, made no mention of any lower Columbia rock art sites (probably because they portaged around the major rapids where the biggest concentrations occurred), other early explorers, such as the Wilkes expedition of 1841 (McClure 1984), did document some of the area’s rock art. Later, around the turn of the century, early photographers, including Edward S. Curtis, took pictures of a few sites, and a German company made and sold postcards showing rock art near The Dalles.

Professional interest in this rock art began between 1910 and 1940, when archaeologists from the Smithsonian Institution and from the University of California at Berkeley did limited field work in the Yakima and Columbia river valleys. Dr. L. S. Cressman of the University of Oregon also recorded some northern Oregon rock art sites at this time. During the two decades of dam building on the lower Columbia (1950–1970), professional archaeologists from the Smithsonian Institution River Basin Surveys, the U.S. National Park Service, and the University of Oregon Museum recorded rock art from The Dalles to Pasco, responding to its imminent destruction, but most of this work remains only partially published. One study team made rubbings of many of the figures at Petroglyph Canyon, one of the area’s most extensive sites.

Avocational rock art researchers, including some professional artists, also took an interest in the area and photographed and copied many designs. The work of these amateurs continues today with the recording efforts of Greg Bettis and the recent publication by Malcolm and Louise Loring of descriptions of more than 120 sites along the Columbia River and throughout northern Oregon (Bettis 1986; Loring and Loring 1982).

Since 1975, renewed professional interest has focussed on rock art near The Dalles. Books by Beth and Ray Hill (1974) and John Woodward (1982) illustrate some of the more well-known sites, but the primary work has been by Richard McClure. Between 1978 and 1983, McClure visited all remaining Columbia River sites and compiled an interpretive synthesis in a volume on Washington’s rock art, as well as a master’s thesis for Washington State University on the rock art chronology of The Dalles-Deschutes area (McClure 1978, 1979a, 1984).

Definition of rock art styles in this part of the Columbia Plateau, and determination of their relative ages, is much easier than in other sections of the region, due largely to McClure’s work. His master’s thesis is the most detailed interpretive treatment of the subject for anywhere on the Columbia Plateau. Malcolm and Louise Loring, whose work has detailed drawings of more than three thousand designs, have provided additional assistance in style definition (Loring and Loring 1982).

The Rock Art

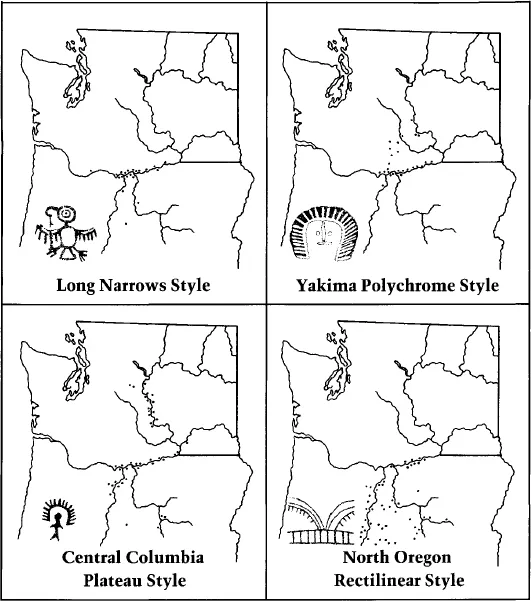

More than 160 rock art sites are found in the lower Columbia area. Almost 90 of these are along the Columbia River between The Dalles and Pasco, Washington, but other large concentrations occur along the middle and lower Deschutes River, and scattered sites are found in the Yakima and John Day river drainages. These sites compose four separate rock art styles, each somewhat distinct from the others despite their general similarities as part of the Columbia Plateau rock art tradition. These are the Yakima polychrome style, the Long Narrows style, the north Oregon rectilinear style, and the central Columbia Plateau style.

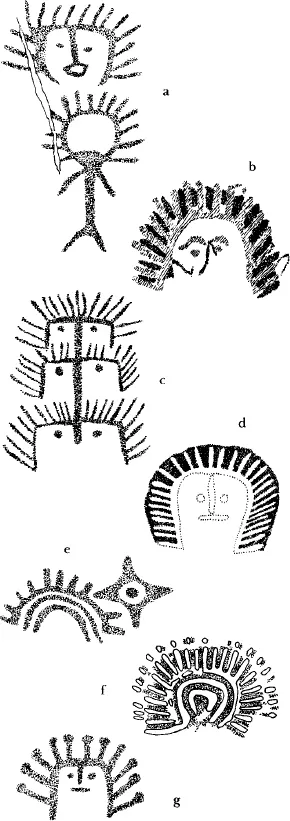

The Yakima polychrome style consists primarily (more than 90 percent at many sites) of red and white polychrome pictographs of arc faces, rayed arcs, and rayed circles (fig. 54). Stickmen with rayed heads and a few abstract red and white human figures are also observed. At many sites some rayed motifs are painted in single colors (either red or white) and sometimes the characteristic rayed-arc faces and elaborate, concentric, rayed circles are inscribed as petroglyphs. More than half of the fifty known locations of this style show the use of white pigment. Yakima polychrome sites occur in the Yakima and Little Klickitat river valleys, and along the entire length of the lower Columbia River. South of the Columbia, only one site, on the lower Deschutes River, has the characteristic arc faces.

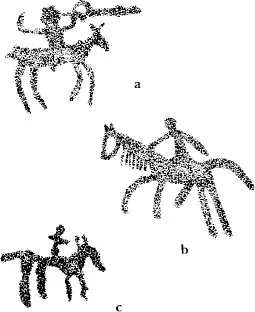

The central Columbia Plateau style, described in detail in the preceding chapter, includes both pictographs and petroglyphs like those found throughout western interior British Columbia and the central Columbia Plateau. In the lower Columbia area, as in these other parts of the region, characteristic motifs are stick figure humans, simple rayed arcs and rayed circles, and block-body animal figures. Animals are mainly simple, spread-eagled thunderbirds, mountain sheep, and deer; many humans have rayed heads or a rayed arc headdress. The common hunting scenes sometimes involve large herds of mountain sheep. Horses with riders appear at eleven sites.

The Long Narrows style (also called Columbia River conventionalized [Lundy 1974] and The Dalles style [Hill and Hill 1974]) occurs as both petroglyphs and pictographs primarily along the Columbia River but also at a few northern Oregon sites (Wellman 1979). On the Columbia River, occasional examples appear as far upriver as Umatilla, but most sites lie between The Dalles and the mouth of the John Day River. In northern Oregon, Long Narrows art is found only at sites on the lower stretches of the Deschutes and John Day rivers. Characteristic motifs are grinning faces; curvilinear abstracts; elaborate, concentric, spoked or rayed circles; and abstract human and animal forms with eyes, ribs, and internal organs depicted. Many of these zoomorphic or anthropomorphic figures apparently represent mythical beings or water monsters. Faces, often wearing hats, have broad grinning mouths, ears, and concentric-circle eyes. The most famous of these is Tsagiglalal.

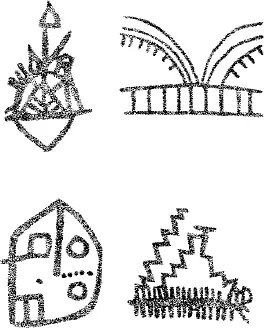

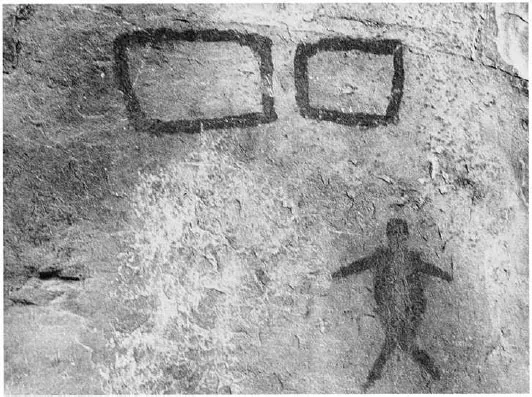

The north Oregon rectilinear style occurs primarily as red pictographs of simple stick figure humans and animals, lizards, tally marks, and numerous rectilinear abstracts. In this latter category are rectangles, ribbed figures, grids, zigzags, crosses, circles, chevrons, rakes, and ladder figures, often combined with one another to form elaborate mazes. These rectilinear abstracts make up more than 50 percent of the paintings at sites of this style in northern Oregon’s Deschutes and John Day river basins (fig. 55).

Sites cluster densely in several favorable locales in the lower Columbia area (map 5; Loring and Loring 1982; McClure 1978, 1984). Many of these are now inundated by The Dalles and John Day dams, or were destroyed by associated construction activities, but a few still exist out of reach of the reservoir waters or in protected areas such as Miller Island and Horsethief Lake State Park.

54. Yakima polychrome style motifs include arc faces, rayed arcs, and four-pointed stars: a, red pictograph; b, d, f, red and white polychromes; c, e, g, petroglyphs. White pigment is indicated on polychrome figures by hatchured areas (b) and outlined areas (d, f).

55. Complex geometric abstract pictographs characterize north Oregon rectilinear style rock art.

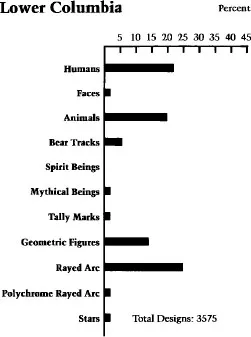

56. Percentages of motifs in lower Columbia River rock art.

Each of these clusters of sites originally had examples of the Yakima polychrome, central Columbia Plateau, and Long Narrows styles, although many are now lost. Certain sites consisted only of single drawings or small groups of figures; others, such as Petroglyph Canyon and John Day Bar, each contained hundreds of figures, and some were the largest in the lower Columbia region. The John Day Lock petroglyph, one site that still exists, has nearly 200 bear tracks—the predominant motif recorded there—and nearly 500 separate designs were noted at Petroglyph Canyon before it was inundated.

Sites also cluster in the Deschutes River drainage, although not as densely as along the Columbia River. Ten sites have been recorded below Sherar’s Bridge, and another cluster of ten sites occurs around the confluence of the Deschutes and Crooked rivers (Bettis 1986). These sites tend to be smaller than the Columbia River sites; the largest have fewer than 100 individual glyphs.

Rock art preservation is poor in much of the lower Columbia area, due to the destruction of so many sites by dam building and road construction. Other sites have suffered vandalism and defacement by paint, chalk, and scratched initials. Although a few panels are fading from natural weathering, this loss is relatively minor compared to the destruction wrought by modern humans. Thus, as in the central Columbia Plateau, a once rich prehistoric art heritage has been significantly reduced in the past fifty years, making the surviving examples an even more precious resource.

Motifs recorded at lower Columbia rock art sites are divided into ten descriptive categories: humans, faces, mythical beings, animals, bear tracks, rayed arcs and circles, polychrome rayed figures, stars, linear geometries, and tally marks (fig. 56).

Map 5. Sites of rock art styles in the lower Columbia region.

Human Figures

Human figures occur at slightly more than two-thirds of the lower Columbia sites. Simple stick figure humans predominate, making up about 70 percent of the more than 900 recorded examples. The preponderance of stick figure humans varies considerably by style, however. Fewer than ten are associated with Yakima polychrome motifs, but 235 of the 250 recorded humans in northern Oregon sites are of this type (fig. 57). Along the Columbia River, 75 percent of human figures are stickmen, but most of these appear to be part of the simple scenes characteristic of rock art in the central Columbia Plateau style.

Other human representations include a few block-body figures, many faces, and a group of abstract anthropomorphic forms that may represent spirits or mythical beings. Both the faces and mythical beings are of sufficient stylistic importance to warrant separate discussion below. The block-body figures are often only variations of the general stickman theme, with oval, rectangular, or triangular bodies and slightly exaggerated features of head, face, or limbs. A few of these portrayals have ribs and other internal organs shown, consonant with the Long Narrows style. Humans are also indicated by hand prints at six sites and a single footprint at another.

57. Simple human figures and rectangular geometries characterize the north Oregon rectilinear style. These are part of the Tumalo pictographs near Bend, Oregon.

58. Hunting scenes involving spears (or possibly atlatl and dart) like that shown in b are older than bow and arrow scenes.