![]()

1/ The Kaulong and “Others”: An Interpretive History

Early in the course of my ethnographic fieldwork among the Tiwi of North Australia during the 1950s (Goodale 1971), I found that I often debated with myself as to how to deal with my own involvement in events that I observed. Since I was part of the observed event, I reasoned that my field notes should contain my participation, including thoughts and feelings along with those observed activities and related information.

As my note-taking evolved during the four Kaulong trips in the sixties and seventies, I gave up keeping a separate diary and began including all kinds of information in my field notebooks: the weather, the goings and comings of people, and my own mood and activities not related directly to the recording of information. Often when it seemed that “nothing was going on” I recorded that, too; at the least it explained the thinness of some of the daily entries. I remember my colleague Frederica de Laguna telling me that “an ethnographer should record everything that she would need in order to write a novel in addition to a monograph.” Consequently, in otherwise idle moments I recorded detailed physical and psychological descriptions of the main and minor characters, the different smells that particular kinds of firewood gave as they burned, the particular pitch of a voice that might indicate that someone was angry and wanted an audience to gather to hear the complaint, air temperatures, bird calls, the sound of light and heavy rain pelting on the thatched roof, and the sound of the small rats having a domestic quarrel in the thatch during their nightly stirrings while I tried to sleep, how it felt to fall asleep to the drumming and singing of a hamlet’s all-night ceremony (singsing), the bone-chill of the hour before the kauk (a small bird) sang out to herald the rise of the sun, the agonizing human quality of the cry of a sacrificial pig being speared, and the moment of fear as I was nearly pulled under the turbulent waters of the flooded Ason River while returning home after visiting in Dulago. In my notebooks, I separated what I had seen and heard from what I thought or interpreted with brackets around the latter. I kept my notes running in chronological order, reasoning that no event is ever entirely “out of place.”

My own approach to the reality of the interpretive nature of ethnographic fieldwork has been to consider that cultural interpretation is to be found imbedded in that central cross-cultural dialogue between informant and anthropologist. I learned early in my professional life that my informants are testing their own theories of the cultural concepts underlying my behavior even as I am struggling to interpret theirs. I believe both parties to the cross-cultural encounter have a mutual aim: to learn the underlying culturally constructed concepts of humanness and social order by which others express rules and strategies, beliefs and understandings of the world in which they live. Why this endeavor to understand the “other” takes place at all within a meaningful relationship may be explained at the simplest level: so that each can learn to predict moods and motivations of the other in a variety of situations. This was extremely difficult for both the Kaulong and their ethnographer particularly in the remote community of Umbi. I believe this difficulty was partly because our basic underlying cultural concepts were so very different. However, a major factor was that the Kaulong of Umbi had had so little contact with Europeans, or, indeed, any “others,” that they lacked experience in assessing cultural differences. Initially, the dialogue I had with informants seemed to be very one-sided; I was making all the effort to understand them while it seemed that they made little or no effort to understand me. Inevitably we grew to understand each other better, and out of this comes my interpretation of their life—and in particular their ideas of humanity.

And so in this introductory chapter, I include myself in the discussion of the setting, in order to provide an adequate account of my field experiences, even while describing the background information necessary for a reader’s comprehension of the particulars of my interpretation of individual personhood among the Kaulong.

THE SETTING

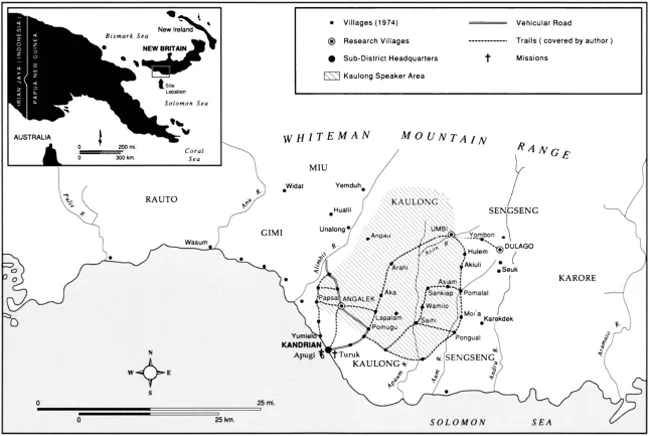

The Passismanua region of southwestern New Britain includes two major language families: (1) the people of the offshore islands who are linguistically related to other Arawe-speakers who live along the coast from west of Kandrian to the Arawe Islands; and (2) people speaking one of the four closely related languages (Kaulong, Sengseng, Karore, and Miu) of the Whiteman language family (Chowning 1969b), who live inland and extend into the foothills of the Whiteman Mountains.

This inland region receives more than 250 inches of annual rainfall. Five major rivers, rising in the Whiteman Mountains, drain south and roughly form the boundaries of the four Whiteman linguistic groups. From west to east: the Alimbit River forms the western boundary of the approximately one thousand Kaulong-speakers. The Kaulong extend along both sides of the river designated on maps as the Apaon but called Ason by the Kaulong living in the foothills of the Whiteman mountain range. The very small numbers (fewer than three hundred) of Miuspeakers live near the headwaters of the Alimbit River and by 1974 were still largely uncontacted. Sengseng-speakers (numbering about three hundred) live on both sides of the Andru River, and to their east are the Karore-speakers. These four language groups are Austronesian (although utilizing a somewhat aberrant vocabulary) in contrast to many other interior peoples of New Britain whose language is non-Austronesian. It was because Chowning expected these heretofore unstudied languages to be Austronesian that we chose this region in which to work. Chowning already spoke two Austronesian languages, Lakalai and Molima, and had an interest in comparative Austronesian. I was encouraged that Austronesian languages were generally considered much easier for a European to learn than the non-Austronesian languages spoken in many other parts of Papua New Guinea.

In July 1962, Ann Chowning and I flew from Rabaul to Kandrian, the administrative post for southwestern New Britain. This small settlement was perched on a narrow strip of flat ground, beside a body of water named Moewehafen by the Germans in the early twentieth century. On the other side of the bay lay three offshore islands, each rising to about five hundred feet above sea level. On one of these—Apugi—the Church of England had a mission. These islands were matched by an escarpment rising to an equal height inland just behind Kandrian.

The European community at Kandrian consisted of Assistant District Officer Dave Stevens, his wife Mary, and children; a patrol officer, David Goodger, and his wife and child; Frank Empin, a malaria control officer; John Snashall, a European medical assistant who manned a small aid post; and a school teacher in charge of an elementary school. A small trade store was run by John, then Eddie, Yun. On the bluff above Kandrian, a Catholic mission housed a European priest and several nuns who ran an elementary school. Below the bluff, squeezed into the flat area, there was a small jail with a detachment of native police billeted nearby.

The personnel at Kandrian changed throughout the twelve-year span of my work. All were enormously helpful to those of us living and working in the bush. They opened their houses to us, fed us, kept us happy with a constant supply of reading matter, and were, in fact, the only outside visitors to our field sites.

Prior to our 1962 trip, Ann and I arranged, through the Department of Native Affairs in Port Moresby, Rabaul, and Kandrian, to be escorted into the interior of the Passismanua region on an exploratory expedition in search of two communities that would be distinct in language and culture but adjacent enough to allow us to visit each other occasionally. We also wished to check the nature of the languages and the degree of acculturation from contact with government and missions. Our interests lay in religion, gender relations, and political organization, and we hoped to study groups minimally affected by contact with non-Melanesians. We had chosen this region because Gilliard (1961) had reported the recency of contact, particularly in the foothills of the Whiteman Mountains, and also had described three rare, even unique, aspects of these societies: twenty-foot-long blowguns, head binding, and the strangling of widows.

We found that, except for the immediate coast and perhaps ten miles inland, this region had never been mapped. Behind the coast was a vast blank on which the words “unmapped—gently undulating” were hardly informative. David Goodger, the Kandrian patrol officer, had spent a week preparing for us a sketch map of the region from his own patrols into the interior. No map gave us any true indication of the nature of the terrain that was to confront us in our “exploratory expedition.” And although we knew that this was the height of the rainy season, we had at that time no conception of what an annual rainfall of 250 inches meant to human life.

On Tuesday, July 17, our expedition left Kandrian. Dave Goodger asked another member of the administrative staff of Kandrian, Malaria Control Officer Frank Empin, to help him in accompanying the two of us. He had also gathered six native policemen and forty-five local carriers to transport our collective gear—tents and camping equipment, clothes, and food. For the initial hour of our journey we all rode on top of a tractor-drawn wagon. The first escarpment was easily climbed, and we rode past the grass airstrip and past the cutoff to the Catholic mission station at Turuk. The road then became muddy and eroded. After we had barely escaped sliding off several log bridges into ditches, we reached the village of Seilwa. From here we began the real journey inland, following wide footpaths leading into the heavily forested interior on the way to our first day’s destination of Aka. The procession was always the same. First were the local carriers loaded down with our gear, some of it packed into aluminum patrol boxes and slung on stout poles carried on the shoulders of two men. Other smaller containers were balanced on the top of the head, the position favored by women carriers. Some of the police went with the first carriers and some followed behind. We almost never saw the carriers from the moment they went ahead to when at last we caught up with them at the end of our daily trek. Dave, Frank, Ann, and I brought up the rear, with perhaps one or two young men or women carrying our travel gear and guiding us over the hazards, holding our hands and encouraging us to advance.

The forest was incredibly beautiful in the sunlight. Huge trees with enormous, buttressing roots rose into the sky and their branches splattered the rays of the sun on the almost bare forest floor. Many of the trees trailed lengthy veils of vines from their tops to secondary trees and eventually to the ground. And there was a pleasing damp earth smell and a lovely coolness out of the intense sunlight of the open road.

The paths we found were treacherous, slippery with packed moist clay, and crisscrossed in every direction by numerous roots to trip one up. It could be fatal to remove one’s eyes from the next foot placement. Very quickly the path began to climb over a continuous series of steep ridges providing slopes on which we slid both going down and climbing up. At the bottom of the slopes were gullies, some with and others without flowing water and often spanned by a single slippery felled log for travelers to inch across above a raging torrent. There were swamps with hungry clinging mud that threatened to consume our shoes, if not our entire bodies. At the top of each slope, painfully reached, there was not a vista by which to measure one’s progress, only the same brown and green forest and the slippery path leading down to the next stream or swamp with its own uniquely frightening excuse for a bridge. I can truthfully say that of all the dreamed-of hazards of life in the deep and uncharted forests of southwestern New Britain, it was only the inevitable challenge of stream- or river-crossings by log that, to the very end, petrified me so that I often had cause to rue the day that I had decided to become an anthropologist.

By the time I reached Aka, I had the beginning of blisters on both heels. Aka was a small village of about eight rectangular houses built in a circle around a central clearing, itself bare of vegetation. The houses were made of rough-hewn planks and the roofs were thatched with lawyer-vine leaves. Aka had a government rest house that Ann and I were offered for the night; Dave and Frank shared a tent. It was here that Ann collected enough of the vocabulary to determine that Kaulong was indeed Austronesian, so that one of our criteria was met.

The following day after breakfast we set off on the next leg of our journey, which took us about five hours of painful progress as I nursed my taped heels. Shortly after we left Aka the true nature of a limestone karst environment became apparent as we climbed the next escarpment; from there on, the way grew increasingly steep, slippery, and dangerous. The narrow footpath negotiated edges of open potholes of undetermined depth, some with underground rivers roaring below, or took the dangerous route on top of slippery fallen logs. Infrequently the path led over broken log fences to make its way through the entangling dense patches of secondary growth in gardens long abandoned. As we neared a small settlement we walked outside strongly bound log fences rising four to five feet high, which protected a growing garden from domestic and wild pigs. We passed through a number of small communities, each under a dozen houses, in which we paused only long enough to drink from a green coconut for refreshment before we reached Arihi.

Dave Goodger had told us that Arihi might be a good place for one of us as it was beyond mission influence. It was, he added incidentally, where a European who was recruiting labor for a plantation on the coast had been murdered in the late 1950s. The convicted murderers had only recently returned from their imprisonment. Arihi was a larger village than those we had previously seen, but we were dismayed to find that two lay brothers of the Church of England, recruited from the Solomon Islands, were also in residence. As we hoped to locate our research in groups that had not yet had mission influence in order to study the precontact religion, we made plans to continue our search for the first “ideal” community farther on into Kaulong country. However, our departure was delayed by the rain.

At the height of the rainy season, we had been very lucky not to have had much rain during the first two days. It now caught up with us and we spent all the next day experiencing our first drenching rain as it turned the central village clearing into a lake. Ann and I sat in the rest house most of the day, imprisoned by the rain and not seeing a living soul, although smoke rising through the thatch of village roofs made us believe that we were not abandoned. At tea time Frank and Dave appeared and we commiserated about the situation over tea as they told us they had slept all day. We were to find out later that both Kaulong and Sengseng fall asleep at the beginning of a drenching rainfall and may sleep for days, rising only to eat a little food and attend to nature’s calls, before stretching out to sleep until the rain abates. Later I, too, found this response to heavy rain easy to make habitual.

The following day, with a destination of Umbi, we moved on over a bush track that went through a region empty of any village settlements and said to be difficult. It was a memorable day for me. Although my blistered heels were fully taped, I was forced by pain to walk entirely on my toes with the heels of my shoes folded down so that they could not further irritate my feet. I contemplated going without shoes altogether, but was persuaded not to do so because the mud was booby-trapped with sharp chert flakes ready to slice one’s flesh to the bone. For nine agonizing hours I trailed behind all the others, with only Frank encouraging me to trudge onward. We followed the now very narrow and sometimes invisible bush track over streams, ridges, and bridges, through heavy forest and the tangle of the occasional overgrown former garden, and through numerous mud swamps, all of which were becoming familiar but no less difficult to negotiate.

Unlike our previous days, we passed no signs of human life or habitation, save one small hamlet with a log-type house inhabited by an old man, an hour from our destination of Umbi. Shortly after this, one of the policemen came back along the path carrying a pressure lamp to light our last mile or so. What a relief to find that a tent had been set up for Ann and me, another for Frank and Dave, and one for the police. And a steaming mug of strong tea was pressed into my hand.

With some apprehension I peeled my soggy, muddy socks off my feet to find that heels and toes and everything in between had been rubbed raw. It was clear to me that I would go no farther in the near future.

Umbi

How does any anthropologist select the particular research community in which to live for a year or more? Not many of us detail the particulars that led us to choose community x over community y, and I wonder if many like me had the choice made for them by some not-so-scientific fact (see, for example, Mead 1938). Whatever the case, I have yet to hear an anthropologist say that they chose their community wrongly or unwisely. I can now fully justify my “choice” by saying that Umbi was the ideal community for one of us to settle in. It was the largest community in the region, with a registered population of seventy-eight men, women, and children. It was Kaulong-speaking and had no missionarie...