![]()

Chapter 1

What language is

The term language has been put to a variety of uses, or misuses. We hear about the language of flowers or body language; people speak of animal language or the language of bees.1 Because so many people confuse language with communication, pretty well anything that communicates may be called a language. Such usages have contributed to a widespread misunderstanding of the role of language in human behavior.

The misunderstanding is twofold. First, there is the persistent confusion between a thing and the uses of a thing. This should not be a problem at all. People who blithely say “Language is (a form of) communication” do not confuse cars with driving, scissors with cutting, or forks with eating. If language were a visible tool that you physically used, the confusion could hardly arise. But language is more abstract than cars or scissors, and when thing and use are both abstract the absurdity of conflating them becomes less apparent. Given the object-use distinction, nonhuman communication systems are not communication, either. Nor, for that matter, are body language, the language of flowers, and so on. Like language, they are representational systems used for communication.

The second part of the misunderstanding arises because animal communication systems,2 and all the other things illegitimately described as languages, differ from language in that they can do nothing but communicate. Language has additional capabilities, and subsequent chapters will show some of the ways it is used to store information or carry out thought processes.3 These by no means exhaust its functions. But one cannot think in body language, or use an animal communication system to store information. If something can be used for only one thing, it is easier to confuse use and thing. The unconscious thought process evolves as follows: animal communication systems are equated with communication, and then language is equated with animal communication systems. So by simple transitivity the solecism “language equals communication” gets committed.

What can different representational systems represent?

The fact that both language and animal communication systems are representational does not mean that they must be accepted as members of the same class. Even from the viewpoint of communication, they differ with respect to what they can communicate and how they communicate it.

Just what kinds of information can be conveyed by nonlinguistic systems? In what is known as body language, a person can convey interest in another by body posture, turning or leaning attentively before the object of attention; by direction and intensity of gaze; by spreading arms or legs in a gesture that signifies openness; and by a variety of other subtle means. Similarly, disinterest can be conveyed by a turning away of the body, a closure of the limbs, a dull or distracted gaze, and so on. But one cannot, in this medium, indicate one’s profession, one’s income, one’s interests, or one’s taste in wine. This so-called language can convey information about states, conditions, or feelings, but cannot convey much in the way of factual information about objective features of the world.

Interestingly enough, body language as used by humans suffers the same limitations as “animal languages.” The latter, with few apparent exceptions, and perhaps no real exceptions, similarly indicate how the animal feels or what the animal wants, but not what the animal knows. Most if not all of these systems have a narrow range of topics: willingness (or otherwise) to mate, willingness (or otherwise) to defend territory, aggression or appeasement directed toward a conspecific, maintenance of contact with other members of one’s group, or alarm calls that warn of the approach of predators.

Alarm calls might, at first blush, be regarded as utterances that convey factual, objective information—“Here comes a predator!”—or even (in more sophisticated species like vervet monkeys) as protowords for the kind of predator to which they are a response. But problems with the concept of meaning make it difficult to know how to interpret alarm calls. There is a world of difference between inferred meaning and intended meaning: between “That cloud means rain” and “The words ‘kindly leave’ mean ‘get the hell out.’ ” If I say “Kindly leave” then I want you to get out, and I intend you to know that I want you to get out. But the cloud neither wants to rain nor intends you to know that it is going to rain. The use of the word “mean” in both contexts blurs the distinction between a meaning that can be inferred by an observer and a meaning that is intended by an agent (and can, hopefully, be interpreted in the same sense by a recipient). The fact that the second proviso may be lacking emphasizes the difference between these two meanings of “meaning.” The cloud can “mean” only if it has an observer, but I can mean in the complete absence of anyone who comprehends my meaning.

So it may well be a mistake to think that a warning cry actually means (in the human sense of meaning) “There is a predator approaching.” It might simply mean “I am alarmed by a predator approaching.” If that were so, then the warning call would be just another case of how-I’m-feeling-right-now. And of course, “I am alarmed by a predator approaching” logically entails “There is a predator approaching.”

But this might suggest that animal calls are merely reflex responses, like our own start of surprise at a sudden loud noise. In fact, things turn out to be slightly more complex than that. Cheney and Seyfarth (1990, chap. 5) have shown conclusively that vervet monkeys (along with other species) do not always call when a predator appears, and that the likelihood of their calling will be influenced by contextual factors, such as the presence or absence of close kin. A better or at least a fuller paraphrase might be “I am alarmed by a predator approaching and I feel you should share my alarm.” This still would lie firmly within the domain of what-I-feel-or-want rather than what-I-know.

Cheney and Seyfarth themselves go somewhat further, claiming that “monkeys give leopard alarms because they want others to run into trees” (1990:174). They may be right, but it would not be easy (even for Cheney and Seyfarth, who are old hands at designing ingenious experiments) to design an experiment that would tease apart the meaning they propose from the meaning “I am alarmed by a terrestrial predator and you too should be alarmed.” For, given that running up trees is the preferred vervet strategy for avoiding terrestrial predators, and that an isolated vervet, faced with such a predator, will give no alarm call but will run up a tree, we can assume that running up a tree is no more than a response to the presence (whether personally observed or inferred from a call) of a terrestrial predator, and thus one which would occur whether the warning monkey wanted it to or not. The more parsimonious assumption is that only the animal’s own state or condition is being conveyed. And in any case, even what-I-want is still very far from what-I-know.

Does the fact that monkeys occasionally give alarm calls when no predator is present constitute evidence for a less parsimonious interpretation? There is considerable if largely anecdotal evidence (see Whiten and Byrne 1988, Byrne and Whiten 1988) to indicate that monkeys will give such calls when they are being attacked by other monkeys or when they wish to keep some tasty morsel of food for themselves. However, there is no indication here that an alarm-sounding monkey specifically wants other monkeys to run up trees. The alarm-sounding monkey merely wants all other monkeys out of its immediate vicinity; its own observations will have sufficed to show it that alarm calls do remove all monkeys from the immediate vicinity of the caller. All we have to assume for this behavior is some degree of volitional control over calling; and we already know that vervets have such control from the fact that they respond differently in the presence or absence of kin.

Thus one cannot conclude that the alarm calls of vervets (or of any other species) convey factual information, even though information may be inferred from them. On the contrary, animal communication systems convey the current state of the sender or try to manipulate the behavior of the receiver. Human language, on the other hand, is not restricted to expressing an individual’s wants or feelings, nor to manipulation, although it can and frequently does serve these purposes. It can also convey an infinite amount of information: not just things like phone numbers, professions, or tastes in music or wine, but the (actual) size of the earth, the (estimated) age of the universe, the basic principles of marketing or mathematics, the habits of the scarab beetle, the behavior of protons, the events that took place in Madrid on May 2, 1808—things that have only the most indirect and tenuous connection, if any, with what the speaker or writer immediately wants or feels.

There might seem to be at least one exception to the generalizations made above about animal communication systems. One such system—that of bees (von Frisch 1967)—does carry factual information regarding direction, distance, and quality of food supplies. However, bees cannot convey any other information, and even information about food is far from complete. When one of von Frisch’s assistants placed a food supply in a tower, the bees that found it failed completely in their attempts to explain its whereabouts to colleagues. Bee “space,” or rather the kind of space that can be represented in the bee communication systems, is two-dimensional: bees can indicate horizontal but not vertical directions and distances. Now there may be dimensions in the universe about which we cannot speak; but, unlike bees, we can speak about all the dimensions we experience, and even a few that we don’t.

It might seem, however, as if bees do breach one limit that otherwise constrains all animal systems: an inability to communicate about anything occurring in the past, the future, or any place other than where sender and receiver currently find themselves. Bee messages refer to objects at some distance from the hive at which those messages are delivered; one might even claim that they refer to events (discoveries of food sources) that are already in the past when the message is given. But these messages are limited to the most recent of such incidents. There is no way a bee can compare the richness of its latest find with that of the source it discovered yesterday, or express a hope that it may find a still richer source tomorrow. Similarly it cannot state that today’s source is twice as far from the hive as yesterday’s, or some distance to the east of it. The capacity to refer to a past event or a remote place does not entail the complete freedom of movement in time and space that language bestows.

For language, of course, knows no limitations of space or time. Even when merely conveying our wants, needs, and feelings, it does so in a much more sophisticated way than animal communication systems do. Although it is hard to prove, most animals appear to be on the level of what Dennett (1987) would call “first-order intentionality”: they have states of mind, but do not necessarily make inferences about the state of mind of others, or even know that others can have states of mind different from their own (see Premack 1985 for a comparison of chimpanzees with human children in this respect).4 Humans, on the other hand, can reach dizzying levels of third- or even higher-order intentionality, being able to say or think things like “I want X to think that I want him to run up a tree because he is a contrary fellow and if he thinks I want him to run up a tree he won’t, which is what I really want.”

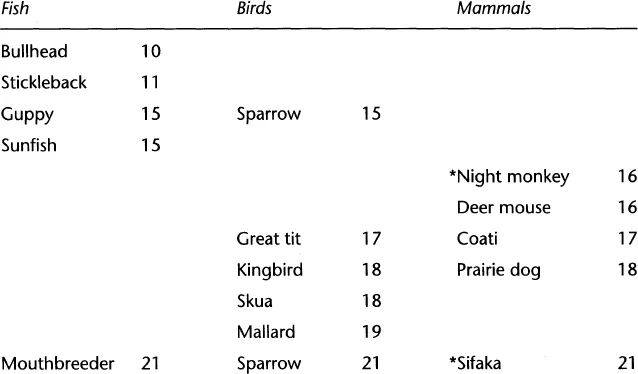

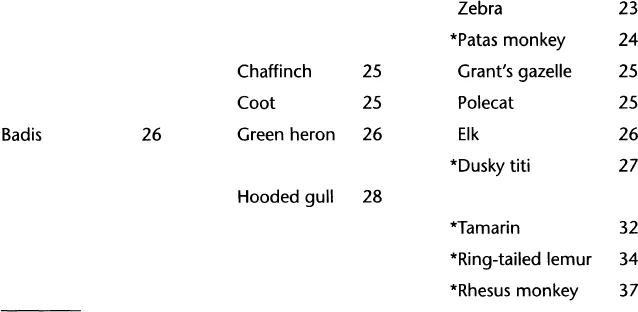

As regards the quantity or the complexity of information that can be conveyed, there is simply no contest between human language and other so-called languages. One might claim that if humans are the most complex creatures, the fact that they have the most complex communication system can hardly be unexpected. But while this is true, it fails to account for the absolute discontinuity between humans and other species. What you would expect, if mere complexity were at issue, would be some kind of gradual increase in the number of things that animals could communicate about, starting with very few among the simpler organisms and finishing with very many (almost as many as we can communicate about, perhaps) among our nearest relatives, the apes. In fact, as Edward Wilson (1972) has shown, there is little difference in the richness of communication systems over a wide range of fish, birds, and mammals (see Table 1.1). All other creatures stand on the same low plateau; we alone tower above it.

This is not just a matter of numerical superiority. Language is an open system, while animal communication systems are closed. By this I mean that no matter how many things we can talk about, we can always add new things. Animal systems are not absolutely impervious to change: the work of Cheney and Seyfarth cited above shows, for instance, that the call repertoire of vervets varies in different parts of Africa, and thus has obviously been added to or changed. But the few changes that do take place do so with the glacial slowness of biological evolution, whereas humans are constantly thinking of new things to talk about: things like sound bites or carjacking that were unheard-of a few years ago. The fact that we can add freely to our list of topics, while other species cannot, indicates a difference in kind, not in degree.

Table 1.1

Number of units in the communication systems of fish, birds, and mammals

*Indicates primates.

Data from Wilson (1972), Figures 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8.

The role of symbolism in communication

One might claim that language shares with other “languages” the use of symbols to convey meaning. But here again there are both quantitative and qualitative differences. The symbols used in animal communication are largely iconic: the relation between the message expressed and the form of expressing it is straightforward and transparent. Lowering the head and/or gaze or presentation of the rump may indicate submission, while expansion of body size by inhaling air or extending hair or feathers may indicate aggression and intention to dominate. However, a reverse relationship between affect and representation (e.g., gaze lowering or rump presentation to signal dominance, expansion of body size to signal submission) is never found. Even among sounds, we find widespread consistencies. Across a wide range of species, according to Morton and Page (1991), high-pitched, squeaky sounds indicate submission, while deep, rasping sounds indicate dominance. There are, of course, exceptions, though the reverse relationship seems nonexistent.

But there is at least one apparent exception to iconicity worth noting. Predator alarm calls might seem a counterexample, since these bear no relation to any noises made by predators, or any other feature of predators. Accordingly, they share at least the arbitrariness of words, and may be important in an evolutionary sense: even if all they express is an emotional reaction to a predator, they may have been the first units to encode such information in a purely arbitrary way. To say this, however, is certainly not equivalent to claiming that alarm calls are a link between animal communication systems and language. It merely suggests that arbitrary symbolism had to begin somewhere, and that alarm calls are plausible candidates for first use.

As well as being iconic, many symbols of animal communication are gradient. That is to say, the length, pitch, or intensity of a call or communicative gesture will vary with the degree of emotion expressed. A bird determined to defend its territory to the death, for example, will sing louder and more continuously than one whose intent is weaker; the vigor with which bees dance will vary relative to the richness of the food source whose location they indicate.

The units of animal communication systems cannot (with one or two exceptions) be combined to yield additional meanings. A rare exception involves cotton-top tamarins; members of this monkey species can combine a chirp (used as an alarm call) with a squeak (used as a general alerting call) (Cleveland and Snowdon 1982). However, in contrast with the relative co...