This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

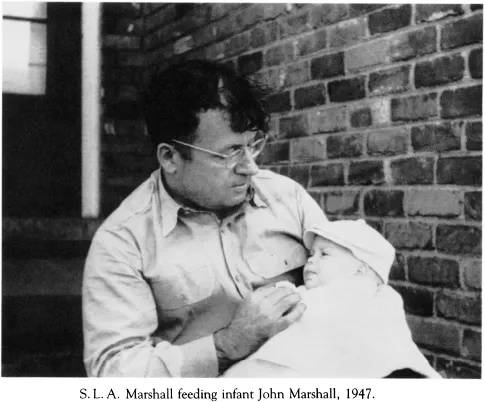

In his prize-winning memoir, Reconciliation Road, John Marshall recounts a road trip around America in search of the truth about his famous grandfather General S. L. A. (Slam) Marshall, author of Pork Chop Hill. In the process he comes to terms with his own past and that of others whose families were torn apart by the Vietnam War.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reconciliation Road by John Douglas Marshall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Detroit Years

I KNEW HIM, or I thought I knew him back then. My grandfather was famous, I certainly knew that, and that had a tremendous hold on me when I was a child. I was not just John Marshall, I was the grandson of S.L.A. Marshall and that made me more important, truly special, at least in my own mind. I did not go around bragging about my grandfather exactly, but I was never that hesitant about mentioning the connection to teachers especially, or others I wanted to impress.

A child's adulation is such a simple thing, so pure, so undemanding, even stronger than love in a way. I did not truly know my grandfather back then, nor did I need to. What little I knew was powerful enough. I knew he was a newspaperman, I knew he was a general, I knew he wrote books about wars, including Pork Chop Hill, which had been made into a movie starring Gregory Peck. And I knew my grandfather traveled all over the world to places I could scarcely imagine; he was always departing for somewhere like Korea, or Israel, or South Africa. And other famous people always met with him overseas, I remember hearing.

Often-told family tales further increased my grandfather's stature in my eyes. He was supposed to have played semi-pro baseball, supposed to have been interested once in a singing career, supposed to have survived numerous plane crashes and other perils. And he often appeared on television—what more could a kid ask of his hero?

Until I was twelve, we lived just a few miles from my grandfather's house in Birmingham, Michigan. We visited there often, always on holidays, but also just to play in his big backyard, or maybe have Sunday dinner. Those 1950's times seem so innocent now, so Ozzie and Harriet and so distant, especially after all the dislocations that came afterward.

Relatives in those days were not just people who sent cards at Christmas and maybe birthdays. They were part of our daily lives, they were our neighbors, they were our friends. Everyone on both sides of my family lived in the Birmingham area; my mother and her two sisters lived less than a mile apart. I remember playing for hours in my cousins' rooms, eating my gramma Povah's steak-and-kidney pie and feeling the crush of my grampa Marshall's bear hug every time we visited his house. To this day, I can still smell the cigar smoke that clung to his skin and his clothes, such a strange odor to a child, sour and sweet and dense.

The two families of Marshalls were particularly close. My grandfather was married to his third wife, Cate, who was much younger, and they had three girls about the same age as my brother, my sister and me. We were all great pals. My grandfather's young family made him seem less like a traditional grandfather to me. We were much closer than that. He was another father to me almost.

The two families of Marshalls even had our own private club back in those days. Our club was called the Phuzzant Buddies, a club that somehow came into being after my younger brother mispronounced “pheasants.” We had special cloth patches made with our Phuzzant Buddy emblem, although we never got around to having them affixed to blazers, as we always said we would. And we had annual Phuzzant Buddy meetings convened around my grandfather's dining room table, very official meetings with minutes taken and actual agenda items discussed, most often who else in the world might possibly be worthy of Phuzzant Buddy membership. It was not an honor we casually dispensed.

We still had our Phuzzant Buddy meetings on Thanksgivings after we moved to Cleveland when I was in the sixth grade. I remember the trek back to grandfather's house, the crowded Country Squire station wagon speeding along the Ohio Turnpike, everyone in such a holiday mood, our anticipation growing about the times we would share again.

But the two hundred miles that now stood between us bred a new distance. Our family visits were far less frequent, and were sometimes strained from our trying to do too much; we wanted to reclaim the way things were, but they usually fell short. The past, it seemed, had passed.

My grandfather, who had been such a strong presence in my childhood, became instead a distant relation who sent presents on special occasions, including a check and a leather-bound Webster's dictionary when I graduated from high school in 1965. Along with it came a note that is still pasted inside the cover today:

“Dear Johnny, I do not think I can make it for your graduation.

Cate is still away and driving that far with the two gals by myself would just take too much out of me.

“I want you to know that I am proud of you. You have performed well in your scholastics, without ever letting your studies interfere with your education [a comment, it turned out, borrowed from Mark Twain]. Having fun as you go along is an important part of life, and so is keeping your sense of humor. You tend to be serious enough. Do not overdo it. The effect on others is unimportant. What counts is that you would finally bore yourself. That should be avoided like grim death. I maintain that a man should always be interesting to himself no matter how dull he seems to everyone else. And one can do that without ever really working at it.

“Work hard, but not too hard. Love well, but not desperately. Sleep sound, but keep one ear cocked for the alarm bell.

“I was going to buy you a piece of luggage; you will be traveling soon. Then I decided, what the hell, you should have some spending money and maybe you do not need any bags anyway. (PS: Try to keep them away from under your eyes.) As ever, SLAM (Poppy).”

I, the dutiful grandson, wrote back:

“Dear Poppy, As always, you were too generous in your gift to me. I can only offer my deepest thanks and say that I banked the money—though that certainly does not mean that it won't soon be spending money. By the way, your hunch about the luggage was correct; Mom and Dad gave me a tremendous American Tourister 1-suit. I greatly appreciated the advice you offer in the letter; in the long run, it will be far more valuable than the money. Thanks again for both. It would be great if our two families could get together soon. Your loving grandson, John.”

A year later, I spent three months living at my grandfather's. He had landed me a summer job as a copy boy on the Detroit News. It was the lowliest position in the newsroom. It paid seventy dollars a week. It put me in heaven.

For years, people had been telling me that “you're going to be just like your grandfather” and I had beamed back, the special connection between us further cemented by each repetition of the phrase. People first started saying that when I developed a chunky physique and they saw the traces of my grandfather's prominent paunch. People continued saying that when I started to do well in English classes, particularly in writing. Those comments intensified when I became editor of my high school newspaper. The words had the ring of truth to me by then. My grandfather had gone from hero to role model for me. I was going to be a writer, too.

Then I was working on my grandfather's newspaper and living in my grandfather's house, the special connection between us acknowledged, at last, by him. I wish, though, I could remember more of that summer, what he said and what we did, places we went together, moments we shared, perhaps a ball game at Tiger Stadium, especially in light of what came later.

I do remember my grandfather was writing a Vietnam book in his basement office that summer, and how he would finally emerge upstairs around 6:00 P.M., exhausted but triumphant, a gimlet mixed by Cate soon raised in toast to another day's writing well done. I remember how he took an interest in what I was doing at the newspaper, solicited my observations on what was going on there, although he did keep his distance, not wanting to put undue pressure on me. I remember, too, how he treated me like one of his family, but also an adult, with few restrictions on when I could come or go, which I appreciated at nineteen. And I remember sitting in his book-lined study when he was gone and working on some of my own writing, pained love poems as I recall, although what I wrote mattered far less than the chance to sit in his place and imagine myself as a real writer, imagine myself as him.

When I left to go back to college at the end of the summer, I was flush with what seemed to have been built between us—a new and closer relationship, more mature, with a real affection and respect for each other that seemed sure to last. And that was reinforced the following spring when he sent Battles in the Monsoon, which he had inscribed: “To John Marshall goes this first copy of the new book—and Johnny, I hope you like it.”

But college brought distance between us. I saw my grandfather only once or twice more before we were reunited on the stage in Charlottesville. By then, he was well-known as one of the country's staunchest defenders of American intervention in Vietnam, and one of the most outspoken critics of the press' performance there (“The most wretchedly reported war,” he wrote in his much-noticed foreword to Battles in the Monsoon. “Never before have men and women in such numbers contributed so little to so many.”)1 S.L.A. Marshall had become The Unrepentant Hawk. My own views were starting to turn in the opposite direction, although I had no interest in debating such matters with him. I still hoped our relationship could avoid being poisoned by the war, as was happening across the generations in so many families.

My grandfather and I were reunited again at Fort Benning. He was the graduation speaker for my officer class at the Infantry School, doing a reprise of the role he had played at Virginia five months before. Again, the close connection between us was underscored in a public ceremony, the famous general and his grandson, now the Infantry lieutenant. In private, though, I found my grandfather distracted by other matters, not as interested in what I was doing in the Army as I had thought he would be. I remember being disappointed about that back then, but wonder now if my grandfather shared my sense of the growing differences between us, and how some things in those divisive days were better left unsaid.

Nineteen months later, little was left unsaid. My letter explaining my decision to become a conscientious objector was followed by my grandfather's letter disowning me and that was followed by years of silence, stony silence.

When my grandfather died six years later, no one in the family suggested I might attend his funeral in El Paso. So I remained in Oregon and sent an arrangement of red roses in my place, roses that my brother later reported had been displayed at the head of my grandfather's casket.

What I felt at the time was mostly regret, regret that no dramatic gesture across the gulf between us, no healing passage of time, nothing would ever bring about our reconciliation. And I suppose I felt some grief about my grandfather's passing. But the truth was—he had been dead for me for many years.

2

Setting out in September

MY COPIES OF MY GRANDFATHER'S OBITUARIES from national publications had long remained buried in a folder marked “SLAM.” I seldom removed the folder from my file cabinet over the years; there seemed no point in dredging up such bad memories. But now, in the wake of the controversy about my grandfather's life and work, I retrieved the obituaries, searching for any hint of fraud, things that might be suspect.

There did not seem to be much, other than the notation he was “the youngest officer in the United States Army in World War I,” the sort of sweeping claim that the controversy is calling into question. Otherwise, the obituaries were prominently displayed, lengthy and full of praise.

S.L.A. Marshall, who stood 5 feet five, was described by Time magazine as “a towering military historian who analyzed all the wars of modern America.” It noted that he was “seldom far from the sound of gunfire,” then continued, “Out of his experiences in the Korean War came his most esteemed books, The River and the Gauntlet and Pork Chop Hill. His writing was distinguished by narrative drive, a gritty attention to the details of combat and a plain-spoken sympathy for the men who suffered and triumphed on the front lines. He could not agree with people, he said, who thought that ‘war is a game in which the soul of man no longer counts.’”1

Could this be the same man who was now being accused of “maligning American infantrymen with ‘Men Against Fire?'” Could this be the same man who was even being castigated by his harshest critic, Leinbaugh, for “knowing nothing about combat?”

The Washington Post used “noted military historian” to describe Marshall in its headline. “As a lieutenant colonel assigned to the Pacific in World War II,” the Post said, “he developed the technique of doing battlefield history by assembling survivors soon after an encounter and interviewing the group about its operations. He used this method later with American troops in Europe, Korea and Vietnam, and with the Israeli army after the Sinai War of 1956.” The Army's then-chief of military history was quoted next: “Marshall specialized in small unit type of action where he would talk to the people involved and elicit the details of what had happened. He was very good at putting it down in a vivid way, and he made people read things that professional historians might make dry as dust.”2

The New York Times' obituary on Marshall started on the front page, that sign of a person's national importance. Marshall was described as “one of the nation's best-known military historians and a prominent figure on American and other war fronts for half a century.” Again, his books were saluted for their “critical acclaim” and their “visceral” realism. A cited review of The River and the Gauntlet described it as “by far the finest book that has come out of the Korean War.”

But the Times also said, “Though his detailed reporting of World War II and the Korean conflict won praise, similar efforts in five books on the war in Vietnam encountered some criticism from writers who said he had lost the larger meanings of the war in a concentration on the minutiae of it. Some critics, moreover, called him a hawk.”3

Now, twelve years later, Marshall was being called much worse. “A liar.” “A fraud.” An instigator of a “peculiar hoax.” I try to investigate these allegations while researching a three-part series about the Marshall controversy for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, where I have worked for years as a columnist. I hear “genius” used to describe my grandfather by both friends and historians. I hear “charlatan” used to describe my grandfather by his critics. I hear very few descriptions in between.

The only way to sort this out, I finally conclude, is to take to the road around the United States. I must complete much more research, conduct face-to-face interviews with those involved in the controversy, as well as those who knew Marshall best—family members, fellow historians, compatriots, people like Gen. William C. Westmoreland and Mike Wallace, if they will see me.

Because I have begun to discover that my grandfather was a far more intriguing figure than I ever suspected. My opinion of him had been colored for years by our bitter break; I saw him as a harsh and unrelenting bantamweight bloated on his own sense of self-importance, with a distinct tendency to be vindictive, even cruel. But a different man was starting to emerge in my research, someone who still wore his flaws like a loud suit, but also a self-made man of the sort seldom seen anymore, someone who did not graduate from high school and still managed to create a historic life.

Writing for the first time about my grandfather and what had happened between us had also forced me to confront the pain of my estrangement from my family and my past. Too long, I had kept it a secret that I had been a conscientious objector. Too long, I had kept it a secret that I was disowned by my own family as a result. And I had let this fester, this wound to my soul. I am not alone in this predicament in late twentieth-century America. Many families are scattered across the country, going about our separate lives, isolated from loved ones at great cost that we may not acknowledge. As writer Norman Mailer has observed, “Very few of us know really where we have come from…. We have lost our past, we live in that airless no man's land of the perpetual present, and so suffer double as we strike into the future because we have no roots by which to protect ourselves forward, and judge our trip.”4

My own journey had seemed so frightfully predictable at one time. I was Wally on “Leave It to Beaver,” right down to the varsity jacket and burr-head flattop, the product of Republican parents in the suburbs and Midwestern public schools, president of the Junior Council on World Affairs, in no way a rebel. Then, I had gone to Virginia, a southern gentleman's school steeped in tradition, no caldron of student activism in the 1960s. Yet somehow I had forsaken my family tradition and refused to fight my country's war.

Was it only those tumultuous times, I wondered now. Was the split with my grandfather an inevitable result of Vietnam and the 1960s? Or was it because of his personality, and maybe my own? Is there a strange gene among us Marshall men ticking like a time bomb through our lives until it inevitably causes our adult relationships to self-destruct? Or could that painful rupture have been avoided, or lessened, or something? And wasn't it time to finally find answers, learn lessons from past mistakes, especially before they...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1 - Detroit Years

- 2 - Setting Out in September

- 3 - Liberating Paris

- 4 - Under Fire

- 5 - Military Heritage

- 6 - El Paso Roots

- 7 - Research Partners

- 8 - Uncharted Territory

- 9 - Across Texas

- 10 - Return to Victory Drive

- 11 - A Protégé's Allegations

- 12 - Westy & Slam

- 13 - Passing through Eden

- 14 - The Demise of Coats & Ties

- 15 - Rising Star

- 16 - Tempting Trouble

- 17 - Bedrock for a General

- 18 - Elegy at the Wall

- 19 - His Brother's Witness

- 20 - Brothers in Conscience

- 21 - In the Wake of the Six-Day War

- 22 - Questions of Fairness

- 23 - Sunday in the Country

- 24 - Eisenhower's Biographer

- 25 - Days of Thanksgiving

- 26 - The Wreath

- 27 - Racing December

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author