eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Making Salmon

An Environmental History of the Northwest Fisheries Crisis

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 488 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Winner of the George Perkins Marsh Award, American Society for Environmental History

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Salmon by Joseph E. Taylor III in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Forestry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 / Dependence, Respect, and Moderation

To understand what went wrong with the industrial fishery and why modern management has failed, we should first step back and ask whether there was ever a successful fishery and what success might mean. Indians, as they do so often in environmental issues, have come to represent a native Eden. In popular literature and commercial advertisements alike, they stand as a symbol of natural simplicity. In the Pacific Northwest, popular culture imagines that an aboriginal balance and harmony existed between Indian fishers and salmon from which later fisheries devolved. Historians also portray the aboriginal fishery as benign in their critiques of the open-access policies of modern management. But their portrayal and critique falter because they also argue that Indians lacked both the numbers and the technology to harm the nineteenth century's massive runs. If Indians could not influence salmon populations, then their fishery does not matter in any historical sense. But look closer. Indians had a greater impact on salmon than we assume, and the success of their fishery has far more significance than Edenic myths suggest.1

The aboriginal salmon fishery provides a useful lens for analyzing the intersection of economy, culture, and nature in the fisheries because Indians did influence salmon populations. Salmon were the largest single source of protein in the aboriginal diet, Indians' fishing techniques were potentially as effective as modern methods, and food storage practices and trade patterns extended consumption in both time and space. Cultural reliance on salmon and technological developments in the fishery allowed Oregon country Indians to consume a huge proportion of the region's runs. Indians' material and cultural relationships with salmon were both more influential and more complicated than popular mythology suggests.

The scale of the aboriginal fishery and the Indians' dependence on salmon posed a potentially significant threat to runs, yet Oregon's rivers still teemed with salmon when whites arrived. How did this happen? The answer lies in the way Indians managed their landscapes. According to anthropologists Eugene Hunn and Nancy Williams, social and environmental management is always a cultural act. “Hunter-Gatherers actively manage their resources” as actively as modern society does. In the Oregon country, historical, ethnological, and archeological evidence suggests that aboriginal spiritual beliefs, ritual expressions, social sanctions, and territorial claims effectively moderated salmon harvests. Myths, ceremonies, and taboos restrained individual and social consumption, while settlement patterns and usufruct rights restricted access to salmon. Oregon country Indians' dependence on salmon yielded forms of respect for the fish that sustained life, and respect shaped human actions that retarded consumption. Indian culture and economy produced a sustainable tension between society and nature.2

In early December 1805, Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery hunkered down at the south end of Youngs Bay near the mouth of the Columbia River. After a journey of almost two years, the sojourners now had to endure Fort Clatsop's soggy monotony. During an uncharacteristically buoyant moment, however, William Clark remarked, “We live sumptuously on our Wappatoe [sic] and sturgeon.” Years later trappers and traders would echo Clark by noting the abundant herds of elk and deer that wandered into their gun sights. Their reports helped foster a popular impression of the Oregon country as a cornucopia that was both accurate and misleading. The region did contain an amazing array of resources, but Indians did not exploit everything available. Rather, they were specialists.3

Indians relied primarily on salmon and a few other items for subsistence. They preferred salmon to other animals because of their abundance and reliability. Salmon runs fluctuate wildly at the extreme northern, southern, and eastern edges of their range, but Oregon country rivers were once among the most accommodating environments for salmon. Moreover, because salmon are anadromous and spawn in freshwater, they appeared at predictable places at predictable times. Fishing was thus a far more efficient way of procuring protein than hunting. It offered Indians a massive and timely supply of protein and carbohydrates. It is no wonder that salmon was a staple of aboriginal diets.4

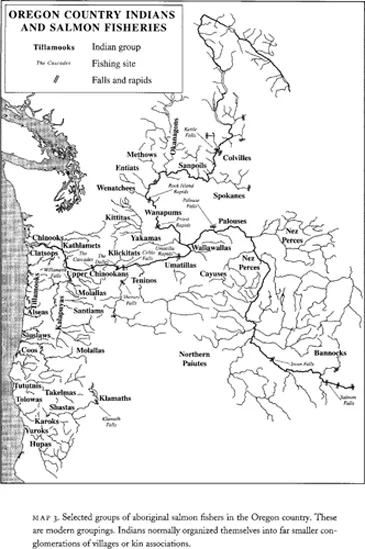

Although virtually all Oregon country Indians (see map 3) specialized in salmon, individual groups employed markedly different subsistence strategies. Geography, environment, and culture thus produced a variety of subsistence patterns within this homogeneous salmon culture.

An individual group's subsistence strategy depended largely on whether it lived on the coast, the Columbia River, the Plateau, or an interior valley. Indians living in coastal and estuarine environments had local access to shellfish, berries, and roots throughout the year, and four species of salmon (chinook, coho, chum, and steelhead) spawned in these streams. Overlapping runs and food storage provided coastal groups a nearly constant supply of protein, so they migrated little and developed dense populations. People living away from the coast had to make greater efforts to procure food. Although six species of salmon (the same as above plus pink and sockeye) spawned in the Columbia River basin, river sites contained fewer additional resources. Groups residing along the lower Columbia still lived in dense, semisedentary populations, but they migrated more often during food quests. They also compensated for local and seasonal scarcities by trading with others along the river. Lush environments ended abruptly at the eastern edge of the Cascade Range. The arid climate widened the spaces between plants, animals, and humans alike. Plateau Indians lived in smaller kin units and searched for roots, plants, berries, and game over vast areas for much of the year. They congregated in larger populations only at fishing sites, root-gathering rendezvous, and winter villages. The people of the Willamette and other interior valleys lived a life similar to Plateau groups except that they often spent more time harvesting roots and less time fishing.5

When salmon began their spawning runs, coastal Indians established temporary camps at opportune fishing sites such as waterfalls and riffles. Nature helped determine where people fished, but culture organized human labor by gender. Men migrated directly to the fishery to repair and install fishing gear. Women and children took a slower course, gathering herbs and firewood for meat drying. During the harvest men fished and women prepared the catch. Spring and summer fishing could be leisurely, but fall was all business; people concentrated on stocking supplies for winter meals, trade, and ceremonies. Once they secured their stores, Indians dismantled their fisheries and returned to permanent villages. Coastal groups usually ended their food quests in September and retired to plank houses until the following March.6

Lower Columbia groups also relied on salmon, but in general the farther inland one went, the more time Indians spent harvesting other resources. Indians living along the lower Columbia and lower Willamette Rivers spoke a common dialect, Chinook, and oriented life around waterways and salmon. In spring before the salmon arrived women harvested wapatos, a bulbous root growing in shallow mud banks, which they consumed or traded. In between runs Indians made sorties for roots, berries, and game. Chinookan speakers fished at locations on both the main river and its tributaries, but the sites at Willamette Falls, Cascade Rapids, The Dalles, and Celilo Falls, where the river tumbled through narrow channels or over falls, provided some of the most prolific fisheries on earth. By October lower-river groups had cached enough food to last until March.7

Indians living east of the Cascade Range migrated more frequently and for longer periods, but Plateau life still centered on rivers. Indians defined their territories by drainage basins. They spent much of the summer at fishing sites along tributaries of the Columbia and Snake Rivers, moving away to protected sites only with the onset of winter. Even one hundred miles up the John Day aver, on the upper Owyhee fiver, on the Drewsey River, and at Salmon Falls on the Snake River, small bands of Paiutes and Shoshones gathered annually to fish the salmon runs. Food quests on the western Plateau began in March and ended in October. Farther east in the Snake aver basin groups had to wait until May and did not winter until November.8

The environment placed limits on dependence, however. The flows of the Columbia and Snake were always heavy enough to accommodate large runs, but where stream size decreased or elevation increased, water levels fluctuated more severely. In areas like the upper Burnt and Grande Ronde avers, stream flows were less stable and salmon runs less predictable. Thus the Cayuses, Nez Perces, and other groups relied less on salmon than westward groups. The Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon marked a rough boundary for the region's salmon culture.9

The Willamette, Camas, and upper Rogue River valleys presented a different set of subsistence challenges. Salmon were scarce above Willamette Falls and in the upper Coquille drainage. To compensate, resident Indians instead developed subsistence patterns similar to those of the Plateau. Migrating frequently to exploit abundant supplies of camases, wapatos, and berries, they then traded these items to coastal or Columbia River groups for salmon. Perhaps predictably, inland groups had fewer ceremonies and myths related to salmon than their neighbors. Indians along the middle and upper Rogue River also migrated seasonally to harvest acorns, berries, and game, but salmon remained the staple food because of the Rogue's abundant runs. Despite varied subsistence patterns, however, salmon bound the disparate peoples and environments of the Oregon country into a coherent culture. Throughout the region, access to salmon influenced the location of villages, group wealth and power, and emphases of culture.10

Salmon's importance as a staple was unmistakable, and it has become a key factor in population estimates. Ecologists use the term “carrying capacity” to describe the upper population limit an environment can sustain. In the Oregon country salmon seem to be the crucial factor determining human carrying capacity. Demographers repeatedly link aboriginal population to local historic abundances of salmon. The correlations are highly suggestive, but they do not by themselves either prove a causal link between salmon and human population or demonstrate that the aboriginal fishery stressed salmon runs. It is possible, for example, that inefficient fishing techniques could have limited human consumption and thus population. It is also possible that Indians were inclined to take no more than they needed to sustain themselves for short periods. The ability of groups to suspend foraging and spend winters in permanent villages suggests a different answer, however. Aboriginal fishing methods could fully exploit the region's salmon runs.11

Indians used a wide array of fishing techniques, but local circumstances dictated which devices prevailed. The middle Columbia River is an example. As the river tumbled through the narrow basaltic cliffs of The Dalles, the swift currents simultaneously aided and frustrated fishers by forcing salmon close to shore and limiting the types of fishing tools used. Only a few implements worked well in those dangerous conditions. Wasco and Wishram fishers living at the great narrows of the Columbia had access to salmon migrating up the largest spawning river in the world, but standing on rock ledges and wood platforms at the edge of the torrent, they could catch salmon only with long-handled spears and dipnets. These methods may seem crude, but they required immense skill. Fishers had to thrust their tools with precision, and a momentary loss of balance could mean death. Farther upstream, Colville Indians suspended reed baskets to trap salmon as they jumped over Kettle Falls. Although spears, dipnets, and traps were not the most efficient devices available, the Wascos, Wishrams, and Colvilles enjoyed the most productive fisheries in North America.12

Where the waters calmed and salmon dispersed, Indians switched to other fishing methods. A few groups used poisons to stun fish before spearing or netting them, but this was rare—poisoning required dense concentrations of fish and very slow currents. Instead, most Indians favored seines and gillnets. Coastal and Columbia River groups constructed these devices using local plant material such as iris, cedar bark, and silk grass, or Indian hemp and bear grass obtained from the Plateau. To keep their nets vertical in the water, Indians attached wood floats and rock sinkers to the top and bottom. Both methods were considerably more efficient and sophisticated than spears, dipnets, and poisons.13

Gillnets and seines possessed different advantages depending on water conditions. Seines worked best in calmer waters like estuaries and eddies, but Indians also used them to create impenetrable barriers on smaller streams. Seines were especially good at efficiently sweeping broad, shallow areas, as James Swan observed of a Clatsop seining party in the early 1850s.

Two persons get into the canoe, on the stern of which is coiled the net on a frame made for the purpose, resting on the canoe's gunwale. [The canoe] is then paddled up the stream, close in to the beach, where the current is not so strong. A tow-line, with a wooden float attached to it, is then thrown to the third person, who remains on the beach, and immediately the two in the canoe paddle her into the rapid stream as quickly as they can throwing out the net all the time. When this is all out, they paddle ashore, having the end of the other tow-line made fast to the canoe. Before all this is accomplished, the net is carried down the stream, by the force of the ebb, about the eighth of a mile, the man on the shore walking along slowly, holding on to the line until the others are ready, when all haul in together. As it gradually closes on the fish, great caution must be used to prevent them from jumping over: and as every salmon has to be knocked on the head with a club for the purpose, which every canoe carries, it requires some skill and practice to perform this feat so as not to bruise or disfigure the fish.

The nets Swan saw were one hundred to six hundred feet in length and seven to sixteen feet deep. Indians used similar nets in the eddies below Celilo Falls.14

Gillnets were even more sophisticated. While seines corralled fish into a confined area, gillnets entangled them in the net's webbing. Indians sized the mesh so fish could swim only partially through the net. When they attempted to back out, gill plates and fins tangled with the mesh. Weaving a useful net required great skill because sizing the mesh was critical. An opening slightly too large or too small rendered the net useless. Fishing a gillnet was also demanding, and keeping it taut and properly aligned in the current required years of practice, especially when one remembers that gillnets were only used at night or in muddy water because salmon avoided the thick-twined nets during daylight.15

Weirs were the ultimate fishing device, and most groups away from the Columbia used them. These “salmon dams” were basically permeable walls built across small rivers, streams, and estuaries. They let water pass downstream but kept salmon from swimming upstream. Indians generally chose shallow locations above tidewater but below spawning grounds; they then drove posts deep into the river bed to support the fencing. This was important because the barrier would back up the stream and put considerable pressure on the structure. Fences were lattices of sticks and branches assembled on portable frames, and each year fishers repaired damaged posts and reinstalled the frames. Some structures were fully portable, posts and all, and many used double weirs and basket traps to corral salmon into small enclosures.16

Fishing demanded prolonged and intense labor. Once they installed the weir, Indians could easily capture trapped salmon with dipnets and spears, but they battled not only the fish but time and the elements as well. Weirs and nets could hinder runs for a time, but eventually the rains would begin. Nature imposed its own time schedule, which Indians could not afford to ignore. They had to catch enough salmon to meet their winter needs and disassemble their stations before the fall freshets or risk losing weirs, platforms, and nets to the rising waters.17

Taken as a whole, the aboriginal fishery represented a serious effort to exploit salmon runs to their fullest extent. Aboriginal techniques could be frighteningly efficient, and in many respects they compare favorably to modern practices. Weirs blocked all passage to spawning grounds; seines corralled large schools of salmon; and basket traps collected without discrimination. Indians in fact possessed the ability to catch many more salmon than they actually did. The Nez Perce claimed at least fifty different fishing sites in the Snake River basin, each of which could produce between 300 and 700 salmon a day. On the southern Oregon coast a Takelma woman claimed her father caught 300 salmon in a single night. Such figures were not representative of all places at all times, but they do suggest the potential intensity of the f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword: Speaking for Salmon

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: A Durable Crisis

- 1 / Dependence, Respect, and Moderation

- 2 / Historicizing Overfishing

- 3 / Inventing a Panacea

- 4 / Making Salmon

- 5 / Taking Salmon

- 6 / Urban Salmon

- 7 / Remaking Salmon

- 8 / Taking Responsibility

- Citation Abbreviations

- Notes

- Bibliographical Essay

- Index