![]()

1

Birth, “Bris,” Schooling

In the Hebrew Bible, fertility is a blessing, and barrenness a problem that requires divine assistance. In the Code of Hammurabi and rabbinic Judaism, barrenness was a justification for a man to divorce his wife and take another.1 In narratives such as the birth of Isaac to Sarah and Abraham, the narrator stresses that God remembers those to whom he promised his blessing and covenant. The motif is adopted in the Gospel of Luke, regarding the birth of John the Baptist, and in the apocryphal New Testament Gospel of James, about the birth of Mary, mother of Jesus.

Despite the significance in biblical narratives about the births of many important figures often following initial barrenness, few rituals accompany the act of birthing.2 Perhaps this testifies to the biblical authors’ strong faith in God’s protection, which might be compromised were anyone, as many later would, resort to protective measures. Did everyday Israelites make use of amulets, incantations, and other techniques to make the experience safer? Most likely they did, but this is not mentioned in the narratives.

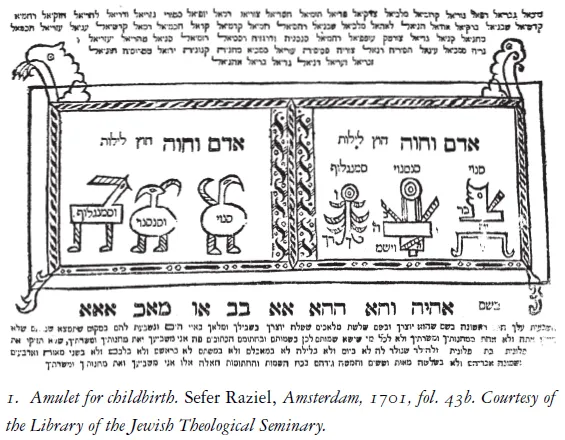

In late antiquity and medieval times, many customs are attested that were thought to protect the mother and the unborn child. A pregnant woman might wear around her neck special stones or a gold coin, part of a rabbit, or an inscription meant to protect against miscarriage. Others would wear a belt on which women had woven or written phrases to protect the mother from miscarriage, hang amulets on the walls of her room to protect her from Lilith, or place a symbolic iron knife under her pillow, all customs that persisted into modern times either in Europe or in the Mediterranean Jewish communities. Christian churches owned relics such as belts for expectant mothers, to protect them during pregnancy.3

BIRTH RITES

The birth itself is described briefly and is portrayed in illuminations from later times as a form of sitting. The account of a woman in labor in Egypt seems to indicate that she sat on two stones placed a small distance apart: “‘When you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool’” (avnayim) (Exod. 1:16), a local Egyptian practice. The meaning of the term “avnayim” is not clear but may refer to birthing stones, as in a magical inscription from an Egyptian papyrus that includes the phrase, “from on the two brick stones of the birth.”4 There are suggestive drawings of a god making human forms on a potter’s wheel that may have developed into the stones on which women, in imitation of the god, delivered a baby.5 Birthing stools are well known even in modern Europe.6

A baby could also be delivered while the mother sat on someone’s knees.7 This is the procedure when barren Rachel asks Jacob to sire a child with her maid Bilhah, who eventually will “‘bear on my knees’” while giving birth (Gen. 30:3). We also see this when Joseph’s descendants are born: “the children of Machir son of Menasseh were . . . born upon Joseph’s knees” (Gen. 50:23). Using the knees as a platform or table area will be retained in Jewish traditions, not for birthing, but for holding a baby boy steady during his circumcision. Elsewhere, the birthing position is described as kneeling. For example, if a distraught mother in labor takes an oath not to have sex with her husband again, an act of impiety for which she must make a sacrifice after her days of impurity (Lev. 12), the phrase used is, “when she kneels in bearing, she swears impetuously.”8

Whatever the mother’s position, we do not know if anything was said to greet the birth—certainly not “Mazel tov!” From a chance remark by the prophet Jeremiah, we see that the father was usually not present at the birth itself. Someone else had to bring him the news: “Accursed be the man who brought my father the news and said, ‘A boy is born to you’” (Jer. 20:15). The presence of fathers in delivery rooms, now common, was still being resisted in the late 1960s in New York City. And since men were not present at birth, they did not write down what usually happened.

In this all-female experience, midwives play an important role in the Hebrew Bible’s descriptions of birthing, especially of a child to an important woman. Called meyaledet (literally, birther) in biblical Hebrew—hakhamah (skilled woman) or hayyah (life-bringer) in the Talmud9—a midwife appears in several biblical accounts of important births. For example, during the difficult breach delivery of twins to Tamar, the daughter-in-law of Jacob’s son Judah, we find: “While she was in labor, one of them put out his hand, and the midwife tied a crimson thread on that hand, to signify: This one came out first” (Gen. 38:28). A midwife assisted Jacob’s wife Rachel in delivering her youngest, Benjamin, a birth that ended in Rachel’s death (Gen. 35:17–19). Similarly, the unnamed daughter-in-law of Eli, the priest of Shiloh, died in childbirth, although assisted by women who are referred to as “ha-nizzavot ’alehah” (those standing over her) (1 Sam. 4:19–22).

Midwives also played a central role in the introduction to the momentous story of Moses’ birth. They foiled Pharaoh’s plan to have all Israelite male newborns killed. The narrative suggests that the use of a midwife was the usual practice for Egyptian women, but that some Israelite women were able to give birth without one:

The king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, one of whom was named Shiphrah and the other Puah, saying, “When you deliver the Hebrew women, look at the birthstool (ha-avnayim): if it is a boy, kill him; if it is a girl, let her live.” The midwives, fearing God, did not do as the king of Egypt had told them; they let the boys live. So the king of Egypt summoned the midwives and said to them, “Why have you done this thing, letting the boys live?” The midwives said to Pharaoh, “Because the Hebrew women are not like the Egyptian women: they are vigorous. Before the midwife can come to them, they have given birth” (Exod. 1:15–19).

This observation reflects the divine assistance that the narrative wants to ascribe to the Israelite women. It also may mean that the biblical narrator thought that use of a midwife was more common among Egyptian women and less frequent among Israelites. The presence of a midwife was no guarantee that a birth would be safe, and the deaths of the mother or of the infant posed constant dangers until very recent times. It was because birth was so dangerous that the rabbis of the Mishnah, by early second-century Palestine, declared that “one may help a woman give birth on the Sabbath and call a midwife (hakhamah) for her even from far away, and one may desecrate the Sabbath over her.”10

Fear of facing this real danger generated rituals, as we learn from Ezekiel, the prophet who was with the exiles from Judah in sixth-century B.C.E. Babylonia. He compares Jerusalem to a newborn: “As for your birth, when you were born your navel cord was not cut, and you were not bathed in water to smooth you; you were not rubbed with salt, nor were you swaddled” (Ezek. 16:4)—all of which presumably was done for normal births. Some apparently abandoned their newborns, for Ezekiel continues: “On the day you were born, you were left lying, rejected, in the open field” (Ezek. 16:5).11

Everything in this passage seems familiar except salting the infant. This practice has a history, often in combination with applying oil, not mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, and it is done today among some Arabs, for example. Greek medical writers like Galen (130–200 C.E.) mention it as being medicinal, but salt is also thought to have the magical power of checking evil.12 We are familiar with the related custom of throwing some spilled salt over the left shoulder.13 Compare, too, the popular Talmudic expression that compares salt to the God-given soul: “Shake off the salt and cast the flesh to the dog.”14 Applying salt to the newborn, then, may have held both symbolic and magical meanings of enhancing or preserving the life of the newborn at the dangerous time of birth. Medieval Christians and Jews continued this practice, and salt was also inserted into the newborn’s mouth during infant baptism.15

Swaddling or wrapping the infant also had a long history, and in medieval illuminated manuscripts newborns are represented as tightly wrapped cocoons.16 By rabbinic times at least, a baby could be placed in a cradle (’arisah).17 In medieval Ashkenaz, a special ceremony is described after birth in which a Pentateuch is placed under the baby’s head in the cradle.18

Although today we may regard certain practices as magical and primitive or as superstitions, there is little objective basis for distinguishing what some call “magic” from “religion.” The actual practices or actions that are performed are all acts carried out by humans who feel so helpless before overwhelming forces that they seek somehow to control either psychologically or physically, or both. (Fig. 1)

In ancient Palestine and Babylonia, where most Jews lived from the first through the seventh centuries, the sources of rabbinic literature, ancient pagan authors, inscriptions, and other archeological findings offer us a variety of incantations, amulets, and rituals, some of which accompanied the birthing process. Many practices were derived and adopted from the cultures of Egypt or Mesopotamia; others may have been produced by local Jews themselves and were borrowed and adopted by Greek-speaking pagans living in the cities of Palestine. In some cases, these were popular practices that the rabbis opposed; in others, the rabbis themselves promoted the practices. Jews who did them made them part of Jewish culture, regardless of their origin. They are part and parcel of lived Judaism no less than the most complicated tracts of Talmud or commentary.19

We should remember that the religious behavior of Jews was not identical with the wishes of the rabbis. After the Muslim conquest in the seventh century C.E., the sway of rabbinic norms increased, but at the same time, some popular practices of non-rabbinic Jews infiltrated the rabbinic norms and changed them. We should also remember that rabbis, including those in the Talmud itself, were practitioners of what we call magical acts and that part of the power the rabbis claimed derived from their charismatic powers.20

This was true among later rabbis who were kabbalists as well, including such figures as Rabbi Israel Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism,21 and it is an error to ascribe magical acts just to the world of either popular culture or outside influences, as though they were not frequently integral parts of Jewish culture at all levels. They were. Several of these practices survived in Jewish communities for hundreds of years, attesting to the belief that they were effective protections against the terrifying experience of childbirth.22

Birth Day Party

No festive meal or other rite at the time of birth is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, and Josephus (first century) observes that the Torah “does not allow the birth of our children to be made occasions for festivity.”23 The Talmud refers to a custom that marked the event in Palestine, where parents planted a cedar tree for a newborn boy and a pine tree for a newborn girl.24 Although this source is often read to mean that the tree was later used to form the child’s wedding canopy, the Aramaic genana being equivalent to the Hebrew huppah, in antiquity huppah meant wedding chamber, not canopy. The four-poled wedding canopy was an innovation in early modern Germany (see Chapter 3).

There also are obscure Talmudic references to a celebration after the birth of a son called shevu’a ha-ben (week of the son) and yeshu’a ha-ben (salvation of the son). In northern France, Rashi interpreted the former to mean the circumcision and the feast that the father made at the end of the week, as though the term meant a time that marked one week after the birth of a son.25 Rashi took the latter term to refer to the redemption of the firstborn (pidyon ha-ben). His grandson, Rabbi Jacob ben Meir (d. 1171), the great Talmudic commentator from northern France and known as Rabbeinu Tam, disagreed.26 He wrote that the word yeshu’a cannot strictly refer to redemption but means “salvation.” The term refers to a party made right after a son is born, when he was “saved” from his mother’s womb.27

That a link between shevu’a ha-ben and circumcision is secondary, and not its original meaning, is proven by medieval texts that refer back to early rabbinic times to a parallel celebration called shevu’a ha-bat for the birth of a daughter.28 As the term itself suggests, shevu’a ha-ben possibly referred to a Jewish equivalent of the Greco-Roman feast that took place for seven days after the birth of a son. Originally, it meant “the son’s birth week” of continual feasting, not just the circumcision feast after the child was a week old, but this practice disappeared even in late antiquity.29

A seven-day feast after the birth of a child is also an early Arab custom and may underlie the term in rabbinic texts, even though the original practice was forgotten by Talmudic times. Muslim women cook and bring things over to the mother and visit her, and the father invites his friends over to celebrate, too. Parallel customs of weeklong feasting developed to celebrate a Jewish wedding (see Chapter 3). Cooking for Jewish mourners is mentioned in the Talmud (see Chapter 4), and there are customs about friends eating with the mourners for seven days of the shiva (literally, shiv’ah=seven), including reciting a special Grace after Meals. Weeklong communal eating is still done after the marriage feast and for the seven days of special meals after a death, but is not done following a birth. The number seven is a lucky number in many cultures.

The interpretation of shevu’a ha-ben as a circumcision party, rather than a weeklong celebration after a birth, was insisted on in several early medieval Palestinian texts, such as Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer, Midrash Tehillim, and Midrash Tanya Rabbati, for example. The midrash observes that Abraham immediately obeyed God whenever he was commanded to do something. When God specifically commanded Abraham to circumcise his son when eight days old (Gen. 17:12), he did so immediately: “And Abraham circumcised his son Isaac when he was eight days old” (Gen. 21:4).

“Hence,” the midrash continues, “you may learn that everyone who brings his son for circumcision is like a high priest bringing his meal offering and his drink offering upon the top of the altar. From this, the rabbis said: A man is bound to make festivities and a banquet on that day when he has the merit of having his son circumcised, like Abraham our father, who circumcised his son, as it is said, ‘And Abraham made a great feast on the day he circumcised Isaac’” (Gen. 21:8, italics added). And, in fact, we know that fathers in late antiquity and in the Middle Ages did make festive parties on the occasion of a son’s brit milah (ritual circumcision, known more commonly as a bris).30

The midrash, however, has invented a proof text and the italicized words are not in the Bible. The verse actually says that Abraham made a great feast “be-higgamel et yizhaq” (on the day Isaac was weaned), not when he was circumcised. By a clever rereading of the Hebrew, this verse now became the scriptural basis of a different religious custom. The midrash in Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer, as we have it, does not explain the linguistic basis of the reinterpretation of that phrase, but Rabbi Jacob ben Meir, Rabbeinu Tam, quotes a version of the passage that does. The midrash reads the verse as though the verb for weaning (higgamel) is reduced to two letters that have the numerical value of eight [h=5 and g=3], plus two letters that contain the ...