![]()

1

VILLAGE AND TOWN

The Communities Transformed by The Dalles Dam

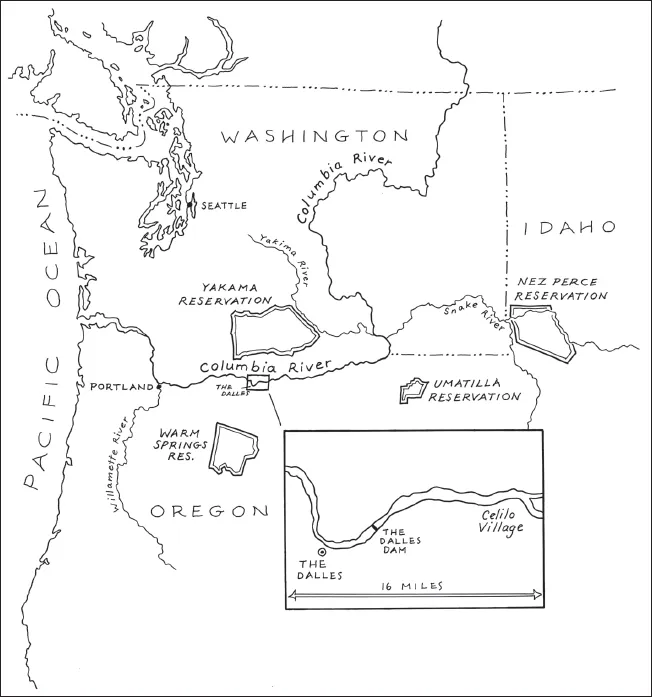

This is a story of two communities located twelve miles apart on the Oregon banks of the mid–Columbia River and the ways in which a federal dam transformed them. The ancient Native fishing community of Celilo Village existed near the treacherous Celilo Falls and Long Narrows for millennia as a hub in a regional network of trade and cultural exchange. Recent emigrants comprising the city of The Dalles settled in the mid-1800s to sell goods to miners, plow bunchgrass into orchards and wheat fields, and, eventually, create a modern American town complete with an international port that would transport goods to and from the interior Pacific Northwest.

In the mid–twentieth century, as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers set its sights on the development of the mid–Columbia River, these two communities would clash over the use of local natural resources and the future of the river. The Dalles confidently celebrated the modernity and economic security that a federal dam and professional river management promised. Celilo Village and the wider network of regional Indians who fished at Celilo Falls recognized the dam project as yet another reallocation of resources used by Indians. A dam would transform prime fish habitat into a slack-water reservoir that would support transportation and power production to the detriment of salmon populations. In addition, the reservoir would inundate the abundant basalt outcroppings and islands that provided excellent fishing sites but thwarted river transportation at Celilo Falls and the rapids of the Long Narrows. The dam, completed in 1957, did not simply alter the riverscape of the Columbia; it transformed river communities and the relations between them.

Although The Dalles Dam would negatively affect a relatively small group of Indian people in a still lightly populated region removed from the centers of national power, it represented a continuing history of federal Indian removal and the appropriation of Indian wealth by non-Indian people. Despite the federal reservation policies of the nineteenth century, the stretch of the Columbia River known as Celilo Falls and the Long Narrows and the community of Celilo Village were recognizably nonreservation Native areas in the midst of a region that had progressively “whitened” over the previous several generations. However, Native control over fishing sites and the village were not without conflict. The Bureau of Indian Affairs1; Oregon State and Wasco County governments; The Dalles City Council and Chamber of Commerce; the tribal councils of the Warm Springs, Yakama2, Umatilla, and Nez Perce; and local governing structures at Celilo Village itself all vied to control and, in some cases, dismantle the community. Furthermore, whites consistently attempted to encroach on treaty-protected fishing areas by blocking access to the river, harassing Native fishers, and even claiming the sites themselves. Nevertheless, Indian fishers and their families successfully remained on the river and claimed it, like the generations before them, as the center of their economic, social, and cultural world.

The proposed dam, championed by The Dalles, threatened to remove Indian people from the river by destroying the fishing stations and salmon runs that sustained Native activity there. It was a threat as significant as that posed by earlier federal policies of removal. In addition, river development, particularly in The Dalles, paralleled the mid–twentieth century federal policies of termination and relocation that sought to end the treaty relationship between the federal government and Native people throughout the country. Relocation supported the removal of Indians from reservation communities to urban areas, a federally funded migration that was meant to sever tribal ties. Termination policy would dissolve Indian reservations, remove federal recognition of Indian tribes, liquidate tribal land holdings, and eventually dismantle the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The federal government’s treatment of Indian people with a claim to Celilo Falls and property at Celilo Village is unsurprising when placed in this context of termination policy and the longer history of removal. The reallocation of wealth from Indian people to non-Indian residents of the region was, for many, an acceptable, even predictable, outcome of national development.3

However, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began its series of public meetings regarding the construction of The Dalles Dam in 1945, it must have seemed both to those who supported the project and to those who hoped to defeat it that anything was possible. Would the federal dam create an economic and cultural gateway that linked the resources east of the Cascade Mountains to the economic centers west of the mountains? Would the city of The Dalles play a key role in the nation’s ability to fight the cold war successfully? Would Indian people put aside intertribal conflict to wage a battle against construction and the pending loss of the region’s most significant fishing area? Would the federal government, after reviewing the protests of both Indian and non-Indian people, reverse the damage done to Columbia River salmon runs and the fishers who relied on them? These were the kinds of issues discussed from the mid-1940s until 1957, when the dam was closed and the reservoir began to rise over Celilo Falls.

THE PLACE

The Columbia River originates in the cool reaches of the Canadian Rockies, from where it winds through the great basalt plateau of eastern Washington, creating the border between Oregon and Washington. It empties a basin of 259,000 square miles, unifying a culturally and environmentally disparate region. The Columbia River Gorge, an east-west corridor characterized by steep basalt formations on the south side of the river and gently undulating hills to the north, dramatizes a rich, diverse river environment. Dominating the western gorge, verdant growth of invasive English ivy, dew-laden five-fingered ferns, and trillium form the undergrowth of Douglas fir forests. Waterfalls, from springtime flushes of unnamed rivulets to the year-round rush of Multnomah Falls, surge over the steep cliffs on the south bank of the river. In areas of the western gorge, rainfall, heaviest in winter and spring, reaches more than ninety inches annually.4 However, to the east, in the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains, the vegetation dwindles with the decline of annual precipitation. Browns replace the greens of the western gorge as lush vegetation gives way to expanses of dry grasslands. It is a striking transition that journalist Robin Cody likens to “driving over a Rand McNally road map with different colored states.”5

The Columbia River Gorge is a labyrinth of craggy rock formations composed of Yakima basalt deposited ten to sixteen million years ago when fissures along what is now the Idaho-Oregon border released hot magma. Where the river now travels through Wasco County in Oregon and Klickitat County in Washington, these ancient basalt formations were once largely exposed, cloaked with just a shallow layer of loose soil that still supports vegetation such as bluebunch wheatgrass. Then as now, westerly winds matched the ferocity of the river’s course through the gorge. The air was gritty and, in the summer months, hot. Winters brought snow, more wind, the bleakness of overcast days. The Columbia River fought its way through the gorge basalt, smoothing sharp surfaces over millions of years. The rocks constrained the river’s course, creating black eddies, whirlpools, and crashing falls.6

The river, which was severely constricted as it passed through a series of rapids at Celilo Falls, was as violent and unforgiving as the landscape. When William Clark traveled along the mid–Columbia River in October 1805, he described it as “agitated in a most Shocking manner … Swels and boils with a most Tremendous manner” as it flowed nearly nine miles westward through the horseshoe-shaped Celilo Falls, Tenmile Rapids, Fivemile Rapids, and Big Eddy.7 A few years later, Alexander Ross described the topography of the rapids as “a broad flat ledge of rocks that bars the whole river across, leaving only a small opening or portal, not exceeding forty feet, on the left side, through which the whole body of water must pass.” The river coursed with “great impetuosity; the foaming surges dash[ing] through the rocks with terrific violence.”8 Rapid currents and exposed rocks created a navigational nightmare. The rapids, backwaters, and eddies also constituted what many considered the best nine-mile stretch of fishing sites on the continent.

Because of a 900-foot drop in elevation from its headwaters to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean, the Columbia River was identified shortly after World War I as a potential hydroelectric source. However, it was not until the Great Depression, when the federal government turned its attention to large, labor-intensive public projects, that a system of dams began to transform the wild river into what historian Richard White calls an “organic machine.” The Dalles Dam is a cog in that machine. Constructed less than 100 miles from Portland, Oregon, at river mile 192, the one-mile-wide Dalles Dam stretches across the river like an enormous concrete “Z” at the eastern end of the Columbia River Gorge.

THE SALMON

An ancient story tells of the introduction of salmon to Native people of the mid–Columbia River. Coyote, disguised as an infant, ingratiates himself to two old women who have selfishly hoarded salmon by damming the Columbia River. When the old women leave to pick huckleberries, Coyote destroys the dam, releasing the salmon into the Columbia River for all the people to share.

According to archaeological records, salmon preceded Native fishers in the Pacific Northwest by at least one million years. Pacific salmon thrived in significant numbers in Asia and nearly every Pacific coastal stream extending into the interior of Oregon, Washington, Montana, Idaho, and British Columbia. Indians of the region have fished for chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), chum (Oncorhynchus keta), pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka) for thousands of years.

Salmon are anadromous, migrating from freshwater mountain streams to salt water (a transformation that science writer Joseph Cone compared to a human suddenly being able to breath carbon dioxide) to head for the rich resources of the sea, where they feed on microbes and small sea life. They return to the freshwater of their origins when they are ready to spawn. This life cycle is special (only 1 percent of all fish species are anadromous), and it has drawn both storytellers and scientists to salmon. Indians and non-Indians alike have rendered the salmon’s life cycle as magical: it embodies the determination to survive, the annual replenishment of a natural resource, and the completeness of nature and its seasons.9

AN ANCIENT COMMUNITY

Abundant Columbia River salmon runs as well as roots, berries, and game from Mount Adams to the north and Mount Hood to the south drew Indians to The Dalles region at least 11,000 years ago.10 At Celilo Falls, where the horseshoe-shaped precipice demanded portage, dozens of villages scattered about the shorelines. A maze of islands separated the small communities and provided fishing sites in the spring and fall. The villages, each an autonomous political unit, faced the rapids or the mouths of tributaries—anywhere the fishing was excellent and accessible. The Indian population may have reached as many as 10,000 in this nine-mile stretch of the river before postcontact disease devastated the tribes.11

Indians fishing at Celilo Falls in 1954. Gladys Seufert photo, Oregon Historical Society, neg. 61313.

This land of basalt and wind perched between the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, the Columbia River, and the semi-arid plains of the Columbia Plateau was the meeting place of two Native cultures: the Sahaptins of Celilo and the upper Chinook of the Long Narrows to the west. On their voyage to the Pacific Ocean, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark distinguished between the “E. nee-sher Nation” to the east and the “E-che-lute Nation” to the west. They were following the lead of their Nez Perce guides and interpreters, Twisted Hair and Tetoharsky, who left the expedition once it entered upper Chinookan territory. The Nez Perce would have been no use as interpreters to the expedition; “Sahaptin” and “Chinook” denote language classifications. Clark recorded that the captains “took a Vocabulary of the Languages of those two chiefs which are very different nonewithstanding they are situated within six miles of each other.”12 Sahaptin speakers rarely learned the Chinookan language of their western neighbors. They often did not have to; enough Chinooks, who were both savvy and wealthy middlemen, were conversant in many languages because it was essential for trade.13

Although language was an audible difference between the two groups, there were visible ones as well. Houses near Celilo Falls were tule-mat dwellings, elongated beehive structures cloaked in woven grass mats. Fish drying in similar shelters filled the air with their smell. Because they were easy to move, the shelters met the needs of a people who participated in the seasonal rounds of food gathering. At the falls below Celilo, Indians built vertical plank-board lodges, similar to those found on the North Pacific Coast. The upper Chinook were fishers who used trade to supplement their catches. Their permanent structures suited their more permanent ways and exemplified their coastal roots. Both types of structures were warm in winter and cool in summer, also providing shelter from the persistent wind.

Before white settlement, Indians traded salmon in what an Army Corps report described as a “sizable commercial trade.”14 Anthropologists David and Katherine French claim that “the importance of trade in earlier times can hardly be overstated. The Dalles was one of the most important trade centers in Aboriginal America.”15 The Dalles was an integral part of a continental trade network that extended west from the Pacific coast east to the Plains, north from what is now Alaska south to present-day California. The marketplace extended well beyond material goods to include languages, social systems, technologies, and mythologies...