![]()

1 INTRODUCTION

Hells Canyon High Dam and the Postwar Northwest

Both nature and people made Hells Canyon's postwar history. Fish swimming from sea to mountains and drifting back again weave two diverse watersheds, the Snake and Columbia, into the Pacific Northwest. Water flowing through Hells Canyon links the Snake Basin to the Columbia. Yet, as the twentieth century unfolded, Snake and Columbia Basin people came to value water differently. In the Columbia Basin, people used water principally as a tool to make hydroelectricity. By contrast, water stored amid the Snake Basin's distinctive topography, soil, and climate made irrigated agriculture the predominant relationship between humans and nature.

Environmental predicates to the human history of the postwar Hells Canyon controversy deserve study in their own right. Landforms and waterways do not merely reflect cultural impressions from humans who have successively occupied the Northwest. Rather, the Snake Basin's natural features and forces have continuously influenced human behavior. Though varied peoples have adapted nature to serve their material needs, the Snake Basin's land and water, its snowfall and fish runs, exercise the prerogative of sovereignty: they make their own history.

The Snake Basin's arable soil, the river's kinetic energy in Hells Canyon, and the rich anadromous fishery in its chief tributary, the Salmon River, exercised power over the controversy about electrifying Hells Canyon (map 1). They were historical actors before they became natural resources. They remained so even after dams began to rise in the canyon. Northwest histories have begun blurring intellectual boundaries that separate culture from nature. Yet any solid understanding of why Hells Canyon became “a controversy” must be grounded firmly both in the water that sustains life in this place and in its human inhabitants' actions. Together, they made Hells Canyon worth fighting for during the postwar years. One human era's dispute about the Northwest's natural elements recast land, water, and nonhuman creatures into new relationships. Thus rearranged, nature in the Northwest still shapes succeeding histories.

The New Deal after 1932 set the stage for the Hells Canyon controversy by making the Columbia Basin depend more on public hydroelectricity than did the Snake Basin. New Deal hydropower strategy subordinated regional biology to national economy and state sovereignty to federal primacy. A decisive moment in the Columbia Basin's hydroelectric transformation came when Grand Coulee Dam transferred power over the region's salmon from state to federal hands. New Deal legal innovations erected an administrative state to govern this new public power domain. Industrial production in World War II consolidated federal control over water and fish after 1941.

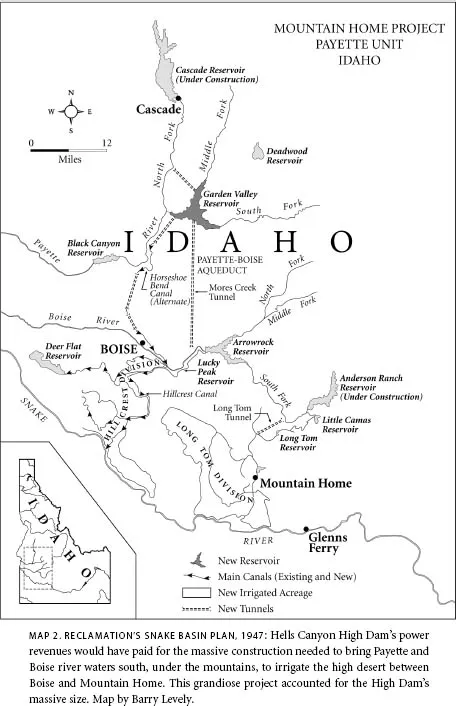

Ambitious and self-confident after easing economic depression and helping win the war, federal hydroelectric managers after 1945 tried to extend their authority upriver from the Columbia Basin. Their postwar offensive targeted the Snake Basin for annexation into the hydroelectric domain. High Hells Canyon Dam's hydropower would fuel their push to the Continental Divide. To reach the Snake Basin, federal power agencies first had to claim economic primacy for power supply in the Columbia Basin. Downriver private utility businesses after 1946 conceded to federal agencies the initiative for meeting their future power needs. Then, between 1947 and 1948, federal managers overcame downriver political resistance to new upstream power dams. Federal managers negotiated with Oregon and Washington a fishery-conservation plan that effectively sacrificed Snake River salmon and steelhead trout to the upriver offensive. Administrative and technological precedents established at Grand Coulee during the New Deal would limit postwar fish-conservation efforts to the lower Columbia River.

Federal and corporate rivals clashed for hydroelectric authority over the Snake in Hells Canyon. Hells Canyon provoked a fierce ideological and economic contest between public and corporate electricity. Idaho Power Company's victory came after what amounted to a national referendum against New Deal hydroelectric strategy. Each contestant invested Hells Canyon with symbolic status. Each worked hard and successfully to nationalize the politics of its hydroelectrification. After 1948, Hells Canyon's fate became a national political issue. Power policy shaped postwar politics when Dwight Eisenhower's 1952 presidential campaign dramatized opposition not only to Hells Canyon High Dam but also to the Democratic Party's entire New Deal hydroelectric strategy. President Eisenhower's promise to build dams in “partnership” with private business recast the Hells Canyon controversy. Idaho Power and High Dam advocates argued their claims before the Federal Power Commission for eight years. This epic legal case about power and primacy culminated in the FPC's 1955 decision to license Idaho Power's three-dam project and the Supreme Court's and Congress' ratification of this choice in 1957.

Idaho Power's political and legal victory unplugged New Deal hydropower expansion in the Northwest. Hells Canyon High Dam perfectly expressed the New Deal credo of using cheap hydropower to exploit river basins' maximum economic potential. The campaign over High Hells Canyon energized new contestants. After 1957, they struggled to define not only the public interest in the Snake River flowing through Hells Canyon but also the scope of the public interest in all forms of nature. This Hells Canyon history explains how and why these things happened.

In the postwar era, in the decade or so following World War II, Americans argued as passionately about electricity as they do today about education. Upwardly mobile politicians won elections, and downwardly mobile ones lost them, because of their stand on power dams. The nation's courts made front-page news, and new law, by adjudicating rival claims to water and the life it sustained.

In Hells Canyon of the Snake River, along the Idaho-Oregon border, in the Pacific Northwest, the postwar controversy about hydropower united mid-western labor unions and southern cotton farmers. General Dwight Eisenhower made Hells Canyon the keynote of the first speech in his victorious campaign for president. Home to more mountain goats than voters, Hells Canyon's uncertain fate nevertheless captivated the nation's citizens.

Hells Canyon ignited such an intense controversy following World War II because powerful popular ideas promised such different futures for the Snake Basin. The Hells Canyon controversy did not demand a national verdict on the question of preserving wildness. Its combatants assumed power dams there would replace a wild river with a managed waterway. So the Hells Canyon controversy was not like the better-known struggle over Echo Canyon, though the issue of dams in both wild places engaged Americans during the postwar era. Both Hells Canyon and Echo Canyon encouraged citizens to consider new values about nature transformed, but each posed different questions about the old ways of living with water.

In the struggle over Echo Canyon on the Colorado Plateau, opponents of dams rallied to the cause of nature untrammeled. A federally designated monument encompassed dam builders' target. Conservationists seized this strategic advantage to articulate the outlines of a new philosophy about natural values in an industrial, urban society. These values—scenic beauty, open space, solitude, vigorous recreation—would inspire far-reaching dislocations in Americans' attitudes and actions as the postwar years waned. Out of this shift grew a political movement, environmentalism, that gives Echo Canyon its special historic significance.1

The Hells Canyon controversy simultaneously engaged many of Echo Park's principals—Dwight Eisenhower and Wayne Morse, Oscar Chapman and Douglas McKay. However, they did not define their differences in terms of protecting wilderness. Instead, the protagonists passionately disagreed for more than a decade about how to dam the Snake River flowing through Hells Canyon. Out of their struggle emerged, unsteadily at first but with growing momentum after 1957, new legal definitions of “the public interest” in flowing water. Legal change raised novel questions about the ecological consequences of industrializing undammed rivers. The Hells Canyon controversy between public and private power stimulated new doubts about the wisdom of wringing maximum economic gain from waters. Appearing in the aggressive, creative legal advocacy against the federal government's Hells Canyon High Dam, these doubts triggered destabilizing shifts in legal thought and practice.

At the Hells Canyon controversy's heart were two deceptively simple choices. Would the U.S. government or Idaho Power Company, a corporate utility, command the river's hydroelectric potential? And how much power would the victor send into humming high-tension lines? Hells Canyon, linking the two great watersheds of the Pacific Northwest, cradled the biggest untapped dam site in the heart of the world's most hydro-electrified region (map 3). Whichever rival won the contest to dam the Snake would direct an energy source capable, if exploited fully, of generating enough new electricity to light every existing factory, farm, and home the length and breadth of the Snake River Basin.2

If it controlled this power, the federal government would become the dominant electricity provider in the Pacific Northwest, from the mouth of the Columbia River to the Continental Divide. To this cause rallied public-power advocates and beneficiaries nationwide: labor unions fearful of corporate mastery, rural people in the Midwest and South who resented utility companies' control over the most basic form of energy, and urban liberals determined to refit the New Deal for postwar social reform. Hells Canyon became their fighting symbol, a testament to their faith in the New Deal campaign against corporate ownership of the nation's most ubiquitous energy source.

Interior secretary Julius A. “Cap” Krug, a veteran New Deal energy regulator, staked public power's claim to the Snake in 1947. “High Hells Canyon Dam is required to be undertaken as a Federal project,” he told the Federal Power Commission, “in order to permit this Department to achieve the goal of the fullest economic development of the land and water resources of the Pacific Northwest.” Any smaller private dam “would be inadequate within just a few years. . . [and] would deny to the people of the Pacific Northwest the maximum use of a great natural resource at a time when it is greatly needed.” Idaho Democratic senator Glen H. Taylor, who was elected in 1944 as a dedicated proponent of New Deal liberalism, blasted private plans to build a small dam in Hells Canyon. “Our natural resources,” he argued, “particularly those resources which belong to all of the people of the United States,. . . should be developed in conformity with the principle of the greatest good for the greatest number, and not for the benefit of any single private individual or corporation.” The federal government had to exploit Hells Canyon's “vast quantity of low-cost hydroelectric power. . . if the people themselves are to receive the benefits to which they are rightfully entitled.”3

Public-power opponents matched their adversaries' passion. For them, the Hells Canyon controversy presented a decisive opportunity at the postwar's outset to trim federal government influence over the economy. Implacably hostile to the New Deal's legacy, private-power supporters made Hells Canyon's fate a national referendum on the New Deal's preference for public control over private initiative. Retired Army Engineers general Thomas M. Robins sounded the charge against federalizing the Snake at the 1951 dedication of a private dam in northern Idaho. “You have an opportunity here,” he told the shivering crowd of four thousand gathered beneath the snow-clad Clark Fork canyon walls, “to make the last stand for state's rights. . .if you will stand firm and back up private initiative, private enterprise, and democratic ways of determining what your region will develop into.” A federal Hells Canyon High Dam, Idaho Power Company general counsel A. C. Inman claimed in 1949, “was essentially a $3 billion subsidized public power development program and should be recognized as such.”4

Government hydroelectric planners sought to annex the Snake Basin into public power's northwestern domain by federalizing Hells Canyon. From Hells Canyon High Dam, cheap public electricity would flow upriver, making the federal government the basin's principal power utility. Federal policy also envisioned selling Hells Canyon power downriver, into the Columbia Basin. There, by the late 1940s, cut-rate New Deal public hydropower had encouraged the nation's most profligate consumption of electricity. Escalating demand for public power, priced at one-third the national average, was outstripping Bonneville Power Administration's supply generated at Bonneville and Grand Coulee, the great New Deal dams on the Columbia River. Together with the Army Corps of Engineers and Interior Department's Bureau of Reclamation, BPA envisioned the High Dam as the solution to both the power shortage they had helped cause and the power domain they sought to expand.5

Reclamation, the Army Engineers, and BPA—builders and operators of the Federal Columbia River Power System—provoked the Hells Canyon controversy. Acting in concert through their new Columbia Basin Inter-Agency Committee (CBIAC) after 1945, these federal agencies sought to direct the postwar trajectory of the Snake River Basin by controlling its electric system. Below Hells Canyon, in the Columbia River Basin, federal primacy had been a fact since the New Deal. Bonneville Power administrator Paul Raver told Congress in spring 1946:

The Bonneville Power Administration as I see it today is a public utility. . . . And when a public utility enters on the responsibility of serving the people of a given area with an essential service it undertakes large responsibilities. . . . We are now in that position for the large part of the Northwest. The government, as I see it, is now in the position of having undertaken a responsibility of supplying the distributing agencies in the Northwest and therefore the people of the Northwest, through those distributing agencies, whether they are public or private, with an essential service, and we can't withdraw.6

Bonneville Power published a manifesto in 1950 for geographically expanding this new hydroelectric society in the postwar years. Large posters, bearing the title “Our Objectives” above Administrator Raver's signature, declared BPA's “fundamental objective is to encourage the use of power from Federal multi-purpose projects as a tool for conservation and development of resources.” The intent of BPA was “to encourage the widest possible use of such power.” To secure this objective, “the Administrator shall build transmission lines,. . . make such power available for sale to existing and potential markets, [and] in disposing of electric energy give preference & priority to public bodies & cooperatives.”7

New Deal transformation of the Columbia Basin shaped the legal, political, and ecological contours of the Hells Canyon controversy. Desperate decisions, made by anxious politicians and aggressive administrators in the depths of the Great Depression, became central to the fate of Hells Canyon and the Snake Basin. Federal policy choices, made during construction of Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams, became precedents justifying postwar expansion of public power into the Snake Basin. By building these two massive hydropower dams on the Columbia River, the New Deal transformed the Columbia Basin between the middle 1930s and the end of the Second World War. Cheap, publicly owned hydroelectricity from Bonneville and Grand Coulee dams industrialized and urbanized a region previously defined by its dependence on farming, fishing, and logging.8 New Deal strategists enforced the sacrifice of rich salmon and steelhead fisheries to intertwined federal goals: cheap public hydroelectricity for urban consumers to finance extensive irrigated reclamation of arid sagebrush steppes. The United States' “permanent program for control” of Columbia River anadromous fish menaced by Coulee Dam in 1939 ultimately determined the demise of salmon and steelhead that ascended the Snake to spawn above Hells Canyon.

After war erupted around the world in 1941, the New Deal's concrete legacy in the Columbia River poured cheap federal power into a transmission grid managed by the U.S. government. World War II accelerated the New Deal's mission of fashioning a distinctive new relationship between people and water in the Columbia Basin. Wartime control of hydropower accustomed federal planners to envision a postwar public-power domain stretching from the Pacific to the mountainous gates of Hells Canyon.9 Even after the war dispelled the Depression in the Columbia Basin, New Deal planners studied how to use cut-rate public hydroelectricity to industrialize and irrigate the Snake Basin.10

Pushing the Federal Columbia River Power System's frontiers upriver, into the Snake Basin, to the crest of the Continental Divide, presented a logical rationale for redeploying the massed forces of capital, expertise, and technology. Bonneville Power's Raver advised his federal colleagues in spring 1946 that BPA anticipated “the extension of its physical facilities and the formulation of governing policies to develop and tie-in multiple-purpose projects in all parts of the Columbia Basin.” The entire Pacific Northwest, in BPA's vision, was “a well-defined and closely-knit region” with “a common interest in water resources.” Therefore, federal power planners should seek to realize BPA's goal of becoming “the Northwest's public utility.”11

Although the Reclamation Bureau and Army Engineers favored different mi...