![]()

PORTLAND PROPER

Neighborhoods, Activists, Nature, and Beer

ROBERT DIETSCHE

Robert Dietsche (1937–) has taught courses in jazz history at Portland State University, Reed College, and Mt. Hood and Clackamas community colleges and taught at Beaverton and Oregon City high schools from 1962 to 1971. He is the founder and former owner of Django Records in Portland and the longtime host of “Jazzville” on Oregon Public Broadcasting radio. His writings about jazz have appeared in Jazz Journal, the Oregonian, Willamette Week, Pittsburgh Press, and the Toledo Blade. Most recently, he wrote Jumptown: The Golden Years of Portland Jazz, 1942–1957 (2005), a history of jazz in Portland. This essay “Where Jump Was A Noun: Jazz in Portland in the 40s,” appeared in Open Spaces (1999).

Where Jump Was a Noun

In the words of the late Hollywood actor, George Sanders: “There never was, nor will there ever be, anything quite like the Dude Ranch.” It was the Cotton Club, the Apollo Theatre, Las Vegas and the wild west rolled into one. It was a shooting star in the history of Portland entertainment—a meteor bursting with the greatest array of black and tan talent this town has ever seen. Strippers (called shake dancers then), ventriloquists, comics, jugglers, torch singers, world renowned tap dancers like Teddy Hale and, of course, the very best in Jazz.

Oh, for a tape recorder and a front row table to Sammy Davis Jr., Coleman Hawkins, Porkchops and Gravy or the Buddy Rich of boogie woogie, Meade Lux Lewis. What a jazz buff wouldn’t give to have been there that August night, hours near the end of WWII, when the whole Count Basie big band appeared. Or the night the Charlie Barnet Orchestra featuring two local prodigies, Ernie Hood and Francis Shirley, took over the place.

In July of 1945 the Ranch, with its tap dancing emcee and celebrity clientele, was the hottest black and tan supper club west of Chicago. Fourteen months later the doors were locked—“A public nuisance,” exclaimed The Oregonian. Billy Holiday had to be cancelled.

The building is still there, the last monument to a time and a place pretty much written out of Oregon history and jazz history in general. What is now called the Rose Quarter used to have a lot of other names, and any cabbie worth his fare would have known that “Black Broadway,” “the other side,” and “colored town” all meant the same thing: the Avenue—namely Williams Avenue, a black commercial center and entertainment strip that used to be among the cheapest land in the city; now it’s among the most expensive.

Fifty years ago you could stand in the middle of what is now the Rose Garden (home of the Trailblazers) and look up Williams, past the chili parlors, barbeque joints and jazz clubs, all the way to Broadway and see nothing but people, all dressed up as if they were going to a wedding. It could be four in the morning; it didn’t matter; this was one of those “streets that never slept.” And what were all these people looking for? JAZZ. There were ten clubs in as many blocks, not counting the ones in the surrounding area. There used to be The Frat Hall at 1412 N. Williams where building inspectors were called in the morning after Ernie Fields brought the house down with his rendition of “T-Town Blues.” Across the street was the Savoy (later called McKlendon’s Rhythm Room) where saxophonist Wardel Gray blew twenty-two choruses of “Blue Lou” never once repeating himself. Down the street was Lil’ Sandy’s where T-Bone Walker liked to play, and around the corner was Jackie’s where one night “Brownie” Amadee showed a young Washington High School student by the name of Lorraine Walsh Geller, who later became a highly acclaimed piano player, how to play bebop. On the corner of Williams and Russell was Paul’s Paradise famous for its after hours cutting sessions.

It’s all gone now, bulldozed away to make room for freeways and other manifestations of urban renewal—buried like some kind of Jazz Pompeii.

Except the Dude Ranch, that triangle shaped building on the pie shaped block that divides Weidler from N. Broadway—two hundred yards northwest of the Memorial Coliseum. Born to be a Hazelnut ice cream factory in 1908, it became a speakeasy in the 20s. Until recently, it was called Multi-Craft Plastics. So instead of dining, dancing and gambling, it’s plastics—residential, commercial and industrial.

The outside hasn’t changed much since the days of the Dude; the inside has, and only an opening in the newly arranged false ceiling reveals the elaborately carved ceiling that once overlooked an even more elaborate dance floor. It was mirrored and slippery and led to an elevated bandstand banked by rows of tables. Above and to the rear was an imposing balcony; that’s where you had dinner.

Photographers were everywhere. Folded cards in the middle of each table read: “You ain’t nuthin’ ‘til you had your photo taken at the Dude Ranch.” Nod your head at the wrong time, and you could find your face on the cover of matchbooks, calendars or in “Let’s Go,” Portland’s main entertainment guide. There were hatcheck girls and cigarette girls and cowgirl waitresses dressed to look like Dale Evans, cardboard six shooters snug in their holsters. Huge handpainted murals of black cowboys lassoing Texas longhorns covered the walls.

“Pat” Patterson, the first black ever to play basketball at the University of Oregon, owned and managed the Ranch along with his pal, Sherman “Cowboy” Pickett. They were inspired by a 1938 Life magazine featuring pictures of heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis learning to ride a horse at an all black dude ranch in Victorville, California. Louis was the Michael Jordan of 1945, even bigger: “If you want to know, watch Joe” was the ‘40s version of “Be like Mike.”

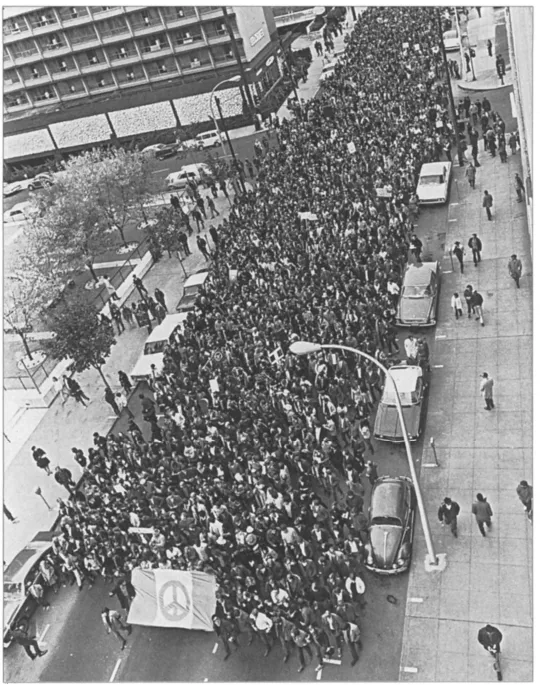

Jazz dance club in about 1949

The Ranch was packed like every other place in this post-war boom town. Tens of thousands of people, many black and from Texas, came to Portland to work in the Kaiser Shipyards or other related areas of defense. On top of that, there were thousands of servicemen passing through, home from the battles in the Pacific and crazy for entertainment. The money was easy; the housing was impossible. All-night movie theatres were converted into sleeping lodges. Restaurants were telling people to stay home. Portland, once thought to be the wallflower of the west coast, had become a twenty-four hour, three-shift, transport city going at about 78 rpm.

The fast and free-spending crowd at the Dude Ranch was a reflection of all that. Among the well-dressed shipbuilders, maids and Pullman porters were Bugsy Siegel-like characters in sharkskin suits and broad Panama hats, in from St. Louis for a friendly game of cards or dice on the second floor. There were pin-striped politicians with neon ties, Hollywood celebrities and glamour queens in jungle red nail polish and leopard coats, feathered call girls and pimps in fake alligator shoes, zootsuited hipsters and side-men from Jantzen Beach looking to get “the taste of Guy Lombardo out of their mouths,” Nobel prize candidates and petty thieves, Peggy Lee’s “Big Spender” and Norman Mailer’s “White Negro,” racially mixed party people, dancing and exchanging attitudes, who could care less that what they were doing was on the cutting edge of integration in a city called “the most segregated north of the Mason-Dixon line.”

Years later the former nightclub owner/civil rights activist Bill McKlendon remembered how important his club and the Dude Ranch were in the area of human relations: “The big name acts at my club and others brought people in from all over. It was the first time that white folks from the west hills and downtown saw that what we were doing here was valuable.”

The music of choice at the Ranch was the blues in its many forms. There were also standards like “Body and Soul” and novelty numbers inspired by the recordings of Louis Jordan and Slim Gaillard, a six-foot-six lunatic who spent the better part of 1943 in the army at the barracks in Vancouver, Washington. Weekends he was at the Frat Hall on Williams Avenue playing piano palms up and singing his big hit “Flat Foot Floogie” (with the Floy, Floy). He was in L.A. in 1945 mostly working at Billy Berg’s. Every month or so he would appear at the Dude unannounced talking that goofy talk of his where everything ends in “O-Rooney” or “O-Voutey” and singing nonsense songs like “Cement Mixer,” which came to him, he confessed, while he was listening to a construction crew outside his studio window: “They were repairing the street, and a cement mixer was going ‘put, put,’ so I started singing ‘cement mixer—putty, putty.’” It became a million seller.

There’s a great description of Gaillard in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road which contains a couple of lines that are among the best in jazz literature: “Slim sits down at the piano and hits two notes, two C’s, and then two more, then one, then two, and suddenly the big, burly bass player wakes up from a reverie and realizes that Slim is playing ‘C-Jam Blues’ and he slugs in his big forefinger in the strings and the big booming beat begins and everybody starts rocking.…”

Slim always had a soft spot in his heart for Portland, even lived here for a while in 1972 playing piano, guitar and bongos at the Travel Lodge near the Lloyd Center. Ten years later he shows up at a jazz party for a radio station as a guest of writer John Wendeborn. Slim walks into the room, looks at the executives in suits, the DJs and sales people, turns his head toward the bar, and yells out, “Hey! Bartender o-voutey got any bourbon o-rooney?”

Eighty, maybe ninety percent of the music at the Ranch was based on the twelve-bar blues, not the down in the dumps country kind played on a guitar or harmonica, but urban blues with horns and sophisticated lyrics. It came in three flavors: bop (now considered to be the beginning of modern jazz), boogie woogie and jump.

When the Ranch opened in May of 1945, just a couple of months before the end of WWII, there was very little bebop in Portland. There were sightings of this revolutionary music as early as October of 1943, when the Benny Carter big band with J.J. Johnson, Freddy Webster and Curley Russell played at McElroy’s ballroom. The next glimmer happened the following year when Tiny Bradshaw and his orchestra with the great Sonny Stitt and Big “Nick” Nicholas hit town.

The first local musician to play this difficult style was Carl Thomas who played off and on here for ten years before leaving to join rhythm and blues star Lloyd Price. He died in obscurity in Seattle without ever receiving recognition as the pioneer of Portland bebop, the first in a line of bop alto saxophonists including Les Williams, George Lawson (the great might-have-been), Dan Mason.

According to two of his best students, trumpeter Bobby Bradford and trombonist Cleve Williams, Thomas was into bop as early as January of ’45, already experimenting with some of the advanced harmonic and rhythmic innovations of Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk. “I don’t know where he came up with it so early,” says Bradford. “They weren’t playing bop on the radio; he may have heard Gillespie’s ‘Bu-Dee-Daht’ (1944) at Madrona Records on Broadway and Williams, the only place in the state where you could find black music.” Cleve added, “I think he got hip at Slaughter’s who always had the latest in jazz records on his juke box; a whole lot of people listened to their first jazz on the box in his pool hall.”

Carl’s big night at the Ranch was on Halloween of ‘45, remembered years later as the night his Frantic Five improvised on “The St. Louis Blues” for one hour. The five included multi-instrumentalist Big Dave Henderson, who left Portland for Oberlin Music Conservatory shortly after this concert, and two students from Fort Vancouver High School: drummer Lee Rockey, an introverted Elvin Jones type who went on to play for Herbie Mann, and bassist Keith Hodgson, who ended up playing with the symphony in Washington, D.C.

Come to find out there were more of the young at bop in the halls of Vancouver High, most of whom were learning their trade on the Avenue or at the Dude Ranch: Bonnie Addleman and Norma Carson went on to jazz fame in New York; trombonist Quen Anderson found his way into the great Georgie Auld’s sextet; and tenor saxophonist Dick Knight got to play with his hero, Duke Ellington sideman Barney Bigard.

Why should this high school have so much talent? Lead alto saxophonist Ray Spurgeon graduated from there and thinks he knows the reason: “The music department was ahead of its time thanks to Chester Duncan and Wally Hanna. They were the ones that developed the program and inspired those whiz kids.”

Bop’s biggest night at the Dude Ranch was December 5, when Norman Granz, “the P.T. Barnum of jazz”, brought in an early edition of Jazz At The Philharmonic—a traveling jam session named after its place of origin in Los Angeles. Some of the biggest names in jazz were there that night: Roy Eldridge; Coleman Hawkins; the ex-Count Basie singer, Helen Humes; and on piano the unknown, undiscovered “high priest of bebop,” Thelonious Sphere Monk, whose bizarre chords had some people laughing and others, like Eldridge, grinding their teeth. Hawkins had convinced Granz to hire Monk for the tour, but it was a mistake says Al McKibbon, the bass player that night: “He was just too far out; I knew where he was going with those funny chords, but I don’t know if anyone else did.”

Apparently the former Quincy Jones trumpet star Floyd Standifer did, as he relates in a recent telephone interview from Seattle where he now lives: “Here was this odd looking guy that was making everyone laugh. I learned about Monk from one of those yearly Esquire Jazz magazines. I hitchhiked in from Gresham, where I was going to high school and playing in a band called East Multnomah Swing Machine. It took me a while as I sat there to realize that what I thought were mistakes and missed notes were right, according to what he was trying to do. He was getting a sound and an energy out of the piano that couldn’t be heard any other way.”

Another musician whose career was turned around that night was Leo Amadee, a round-faced, quiet jazz pianist from New Orleans by way of San Bernardino. Boogie woogie and swing piano were his specialty when he arrived in 1943. After he heard Monk at the Dude, “Brownie,” as he was called, disappeared, Sonny Rollins style. When he returned to the Ranch, he had absorbed the elements of bop piano. He stayed in Portland until 1948, when he left for San Francisco, but not before introducing many young aspiring jazz piano players to the world of Monk and Bud Powell. His influence on the history of jazz piano in Portland cannot be overestimated.

The blues, boogie woogie style, was ten times more popular than bebop with the crowd at the Ranch. Bop came out of New York; it was intellectual and, unless you were Teddy Hale, not recommended for dancing. Boogie woogie, on the other hand, was a by-product of lumber camps and railroad yards. The repeated eight to the bar figures in the pianist’s left hand echoes a train rumbling over the track. It was working-man’s music that could substitute for a whole o...