![]()

1

BOYHOOD IN PENNSYLVANIA

In the spring of 1937 a young couple, Howard and Alice Zahniser, launched a canoe into the upper Allegheny River near Olean, New York, and headed for Tionesta, Pennsylvania. For the next two and a half weeks they had a lovely time floating and paddling down the river, making their camps on its banks or its islands, cooking over fires, watching birds and deer, and visiting with people in the small towns along the way. Alice was pregnant with the couple's first child; indeed, they had made the journey now partly because they knew that this might be their last chance for such a canoe trip. The year before, the Zahnisers had honeymooned in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. Their trip to the West had been splendid, but their paddle down the Allegheny River was an even greater pleasure. For Howard, the river carried special meaning. He had grown up in the small town of Tionesta, where the Allegheny and its banks had been his playground—a source of great wonder and enchantment—and the birds and other animal residents had been among his childhood companions. He was familiar with the rhythms of this great river, and now he was introducing Alice to the center of his boyhood world.

By 1937 it had been more than a decade since Howard had lived in Tionesta. Since graduating from Tionesta High School in 1924, he had gone to college in Illinois, and from there to the nation's capital, where he had found employment as a writer and editor at the U.S. Biological Survey in the Department of Agriculture. At the Survey he became acquainted with biologists and with the work they did to understand wildlife and its habitat needs. During the leisurely canoe journey down the Allegheny River, Howard had a chance to reflect on all of this. As he did, he realized that his transition from a small rural community to a career in a major metropolitan area set him apart from his ancestors. Many generations of Zahnisers had lived and died in the farmlands and small towns of north western Pennsylvania and had thrived on the quiet, unfrenzied pace of life in the region. To them, the Allegheny Plateau was a lifelong home.

According to the family history, the Zahnisers had “always been and still are a distinctively country folk who love to keep in close contact with nature.”1 The Zahniser family originated in small towns and villages in western Germany's farm country around Landau, in the Palatinate region just north of the French border. This was a rural region with “a sturdy and thrifty class” of hardworking farmers.2 One of these residents, Valentine Zahneisen (a name that means “tooth-iron” in German, referring to an instrument then used by dentists), lived in the hamlet of Moersheim. Valentine and his Swiss wife, Juliana, had two sons. Although not poor, the Zahneisens were drawn to North America, where they understood that land was plentiful and new opportunities beckoned. In their case, Valentine's health apparently was the prime motive, for his doctors reputedly advised him to relocate to a more favorable climate. In 1753, Valentine and his wife and sons left their home for America, joining thousands of other Germans from the upper Rhine valley and the Palatinate region who were moving across the Atlantic Ocean. Tragically, Valentine and his youngest son died on board ship, leaving a heartbroken Juliana and her oldest son, Matthias, to complete the family's journey to the new land. They arrived in Philadelphia in 1753, and when Juliana found friends from Germany in Lancaster County, a center of German settlement in the eighteenth-century American colonies, the family settled there. After the American Revolution, descendants of the first Zahnisers moved over the mountains into western Pennsylvania, which became the epicenter for generations of Zahnisers.3

As the years passed, some members of the family became Presbyterians, while others joined the Methodists, whose church was not formally established in America until the early nineteenth century.4 Methodists had enjoyed substantial growth in England and in the United States in the early and middle nineteenth century, and by 1844 they had become the largest denomination in the United States, with more than one million members.5 By that time, Methodists had also become divided over such matters as rented pews, adornment in dress, singing by choirs, and the use of musical instruments during services. For some Methodists, these practices signified that the church had become too secular, too much influenced by worldly pursuits. The national crisis over slavery in the 1850s added to the divisions, and highlighted for some the importance of adhering to high moral principles.6

One result of this cleavage was the emergence of Free Methodism, a conservative sect born in New York State in 1860. Free Methodists sought to return the church to traditional practices of conducting services without choirs or musical instruments, and they urged that members dress plainly, without wearing gold, pearls, or other ostentatious jewelry, and refuse to join the Freemasons or other similar groups.7

As the Zahniser family blossomed throughout western Pennsylvania in the nineteenth century, Free Methodism became their central faith. It also became the profession of several men in the Zahniser clan. Henry Martin Zahniser, great-grandson of Matthias, and his wife, Elizabeth DeFrance, had ten children. Five of their sons became Free Methodist ministers, including their youngest child, Archibald Howard McElrath Zahniser, who was Howard's father.

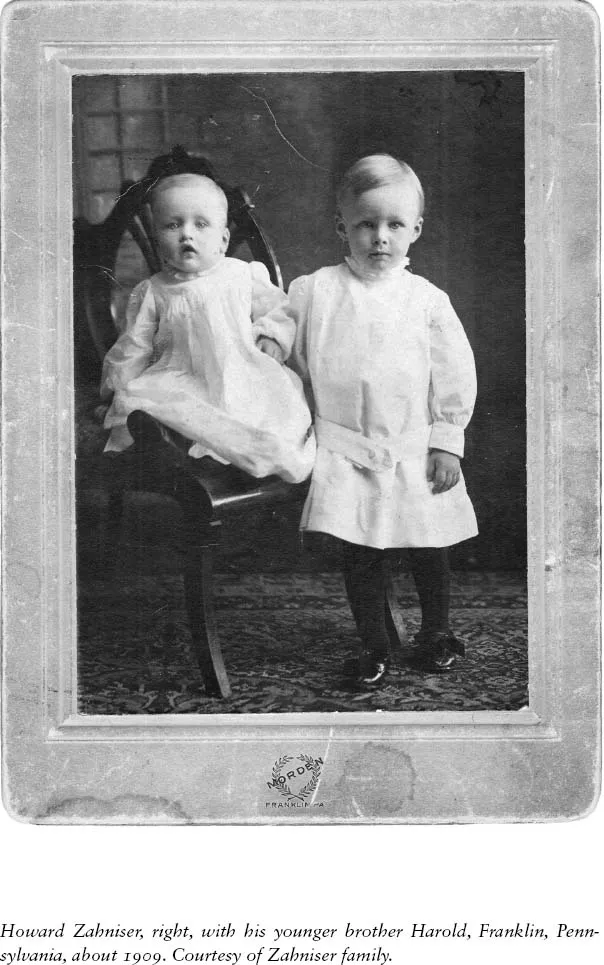

Born in 1880 in Mercer County, Pennsylvania, Archie grew up on a farm a few miles north of Tionesta on the Allegheny River. Drawn to Free Methodism as a boy, he converted to the church at age seven, thanks in no small part to the influence of his older brothers. The boy learned from his brothers how to speak publicly and preach effectively, and he soon found that the life of a minister suited him. He took a four-year course prescribed for traveling preachers in the Free Methodist church, then made his way through the church ranks from full member to preacher to ordained deacon, and was eventually ordained an elder and general conference delegate. In 1902, following his ordination as an elder, he was transferred from the Pittsburgh conference to the Oil City, Pennsylvania, conference. Thereafter Archibald served pastorates at several communities in the northwest part of the state.8 In 1903, while residing at Port Allegany, Archie married Bertha Belle Newton, a teacher from McKean County and a recent convert to the Free Methodist church.9 In 1904 the couple had their first child, a daughter named Esther who died at six months of age. Grief-stricken, Bertha hoped during her next pregnancy for another daughter, but instead gave birth to Howard, their first son, on February 25, 1906, in Franklin, Pennsylvania.10

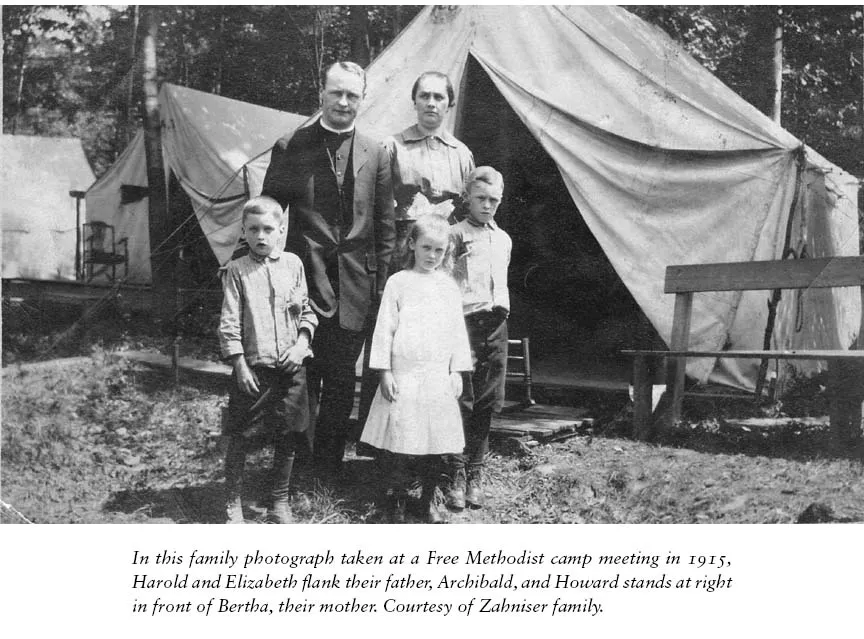

There is little doubt that each of Howard's parents shaped his personality and interests, and instilled in him an interest in nature and an even-tempered disposition that later served him fruitfully throughout his career. Archie and Bertha lived under a powerful sense of higher calling, by a deep devotion to their faith and church, and by a strong desire to help others in their spiritual lives. Their convictions and faith deeply affected Howard, his brother, Harold, and his sisters, Elizabeth and Helen, all of whom learned at an early age the value of service. From his minister father, Howard came to understand the power of faith and of dedication to one's calling, and that finding success in that calling required patience, endurance, and a sense of humor. His father, according to an obituary Howard wrote in 1933, had a character marked by “goodness and sympathy,” took a keen interest in public affairs, and “was always ready to converse on the problems of politics and government, or on social problems in general.”11 As a lifelong supporter of temperance and a devoted member of the Prohibition Party, he was greatly disturbed by the repeal of Prohibition in 1933. Archie was an avid reader and writer, and contributed articles on church doctrine to The Free Methodist and other religious periodicals.12 Archie's devotion to his faith and to public affairs instilled in young Howard a sense of moral purpose and mission blended with kindness and generosity.

Bertha, Howard's mother, reinforced Archie's influence and contributed particular values of her own to the family. Bertha was a devoted wife and mother who followed her husband on his three-year terms as minister to small towns throughout northwestern Pennsylvania. Uprooting themselves every few years, the couple resided in Mayburg, Kellettville, Franklin, and Union City. Always struggling to maintain her family on a minister's salary, Bertha mended her husband's and children's clothes as best she could, scrimped and saved to buy household amenities, and supported her husband in his determination to avoid debt. The couple nevertheless tithed regularly to their church. Howard's younger sister Helen has recalled that Bertha and Archie both “forsook any pursuit of worldly possessions for the higher values of social, spiritual, nature, and humanitarian, religious pursuits.”13

Compared to Archie, Bertha had little sense of humor, but she loved music and took great pleasure in singing hymns at church in her lovely soprano voice. Because Archie could not carry a tune at all (a trait he passed on to his son Howard), Bertha often led the congregation in singing. Her singing sparked in Howard a lifelong love of music, especially choral, and later he would be drawn to the love of his life, Alice, for her talents as a singer. Bertha also took a leadership position in the church, serving as president of the Women's Missionary Society. Howard's sister Helen remembers her as having “a very strict conscience [and] adherence to principles” and as thinking that “what was important was not how one looked [or] dressed but how one acted and behaved.”14 In addition, Bertha helped widen her children's outlook with her special interest in missionary work, inspired by her own sister Luella, who spent years as a missionary in Africa. Luella later operated a home for orphan girls in St. Louis, capping a lifetime of social activism that served as a model for Howard and his siblings.15

As a boy, Howard benefited immeasurably from his parents' devotion to reading. Family reading sessions frequently served as a source of entertainment on evenings when his parents gathered the children around and shared their favorite poetry, fiction, and other books. The experience had a special intimacy that Zahniser liked, and the stories themselves fired his imagination.16 Among his favorite books was The Story of John G. Paton, Or Thirty Years Among South Sea Cannibals. Authored by the Reverend James Paton, the book chronicled the work of a missionary and his family among native peoples in New Hebrides. In distinctly Victorian prose, Paton sharply contrasted the cultures of Scottish Christians and South Pacific natives. Exhibiting common racist assumptions of the time, Paton extolled the superiority of the Christian outlook and the “civilized” habits of Europeans to the lifestyle and culture of the natives. The book intrigued Howard on several levels. Set in a distant land, it was filled with exotic animals and plants as well as native peoples who seemed to delight in their proximity to nature while also appearing to seek a Christian and “civilized” life.17 The book built on the interest in overseas missionaries that had first been awakened by his Aunt Luella. At a deeper level, it also influenced his youthful ideas about the ideal relationship between people and nature.

Although the young man was thrilled by stories about natives in faraway places, he also grew enchanted with the outdoor life close to home. The small towns of northwestern Pennsylvania lie within the Allegheny plateau, a beautiful landscape of forests, valleys, and rivers that offered endless delights to a young person. Howard's first outdoor love was birds, an interest stirred by his fifth-grade teacher in Ellwood City, Evelyn Spencer. Spencer took students to her country home at the end of the school day and conducted a Junior Audubon Society. She gave them Audubon Society bird-study leaflets, urged them to read pocket guides to birds, and taught them how to recognize particular species by sight and sound. It was at her home that Howard saw his first Baltimore oriole, a discovery he remembered throughout his lifetime of special affection for that species.18

He was so taken with bird life that he began to acquire books on the subject, including a two-volume study by C. M. Weed, Bird Life Stories: Compiled from the Writings of Audubon, Bendire, Nuttall, and Wilson. He probably also read Florence Merriam Bailey, whose volumes Birds Through an Opera-glass (1889), Birds of New Mexico (1928), and Birds of Village and Field (1898) were standard works at the time.19 He relished Olive Thorne Miller's works, including Bird-ways, In the Nesting Time, and Little Brothers of the Air.20 Later, while on hikes as an adult, Zahniser would pause to listen intently to birds, and he acquired records of bird songs.21 He loved to watch and listen, while he also took delight in knowing that animals kept occupied in their own lives without regard for the human world. In enjoying their independence, he yearned to understand how humans might best share the world with other species.

If parents and teachers helped spur Howard's early interest in nature, so did the landscape surrounding Tionesta, the small town in northwestern Pennsylvania where he spent his teenage years. The seat of Forest County, Tionesta perches on the side of a hill on the east bank of the Allegheny River. Howard's father had become a district elder in the Free Methodist church, a position that freed him from the standard three-year term in each church and thus enabled him and his family to stay in Tionesta from 1920 to 1926.22 Archie and Bertha bought a house on Bridge Street, about 500 yards uphill from the river.

Tionesta had a characteristically small-town ambience. Residents knew their neighbors, news and gossip traveled quickly, and the atmosphere was friendly, open, and informal. This setting shaped Howard's upbringing and values. He developed a love of neighborliness, a respect for the sort of openness and intimacy that Tionesta offered its residents. Of course, small-town togetherness is easily idealized, presumed to be free of all conflict. Although Tionesta undoubtedly had its internal divisions and its share of difficult personalities, the intimacy of the community helped Howard develop an awareness of the social glue of human groups. From his parents and the townspeople alike, he learned how to get along, how to listen and be mindful of others. It was a lesson that sharpened his appreciation of a shared existence and of democracy.

Located at the confluence of Tionesta Creek and the Allegheny River, Tionesta was heavily reliant on extractive industries, most notably oil and timber.23 Timber companies floated white pine, cherry, and hemlock logs down the river to the sawmills that dotted the banks of Tionesta Creek. Following the discovery of oil in 1859, the Allegheny River served as a transportation artery to Pittsburgh. These industries spawned related enterprises as...