![]()

1 WATER'S EDGE

I followed the call to arms as a young boy, Drawing sharpened sword to confront the hardships of these times.

A hero meets adversity not looking at the ground, For an enemy's scorching hatred can never burn the sky.

—Nguyễn Trung Trực, October 27, 1868 1

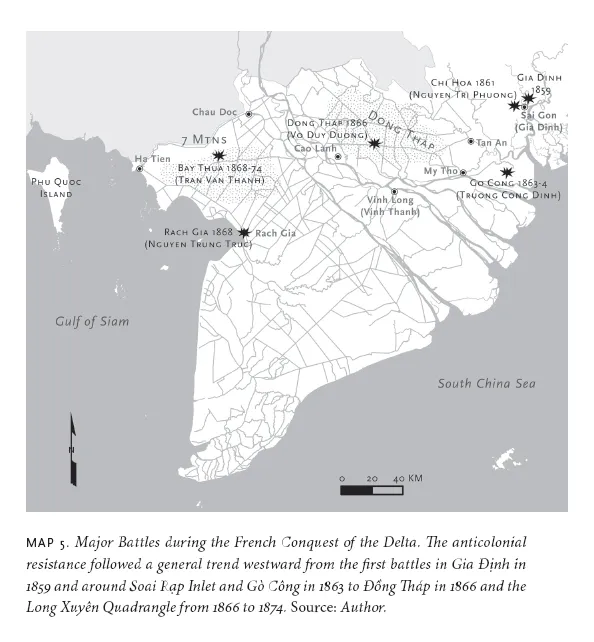

French colonial rule in Indochina began in 1859 after a series of violent engagements on the water. After their show of gunboat diplomacy near the Vietnamese capital in Ðà Nẵng Bay unraveled into a near defeat, the French fleet retreated from the heavily protected central Vietnamese coast. On February 17, 1859, the French fleet recorded its first victory over the Vietnamese at their southern fortress Gia Ðịnh (Sài Gòn) (map 5). Two frigates, three steam-powered gunboats, three transport ships, and one steamer began the assault at dawn with round after round of cannon fire. French and Spanish forces, together with a locally recruited band of mercenaries, launched an attack on the citadel walls that by midafternoon ended with the capture of the fortress and the raising of the tricolor.2 Despite this relatively quick, shock-and-awe victory on the shoreline, fighting continued for two more years just kilometers inland from the riverbank with no major French advances. Nguyễn Tri Phương, southern commander of Vietnam's royal army, blocked access to upstream areas beyond the French docks at Sài Gòn and Chợ Lớn. While French entrepreneurs and military units built a modern wharf in the city, the Vietnamese camps outside Sài Gòn grew to twenty-one thousand troops forming a line of forts with a new headquarters at Chí Hoà (near present-day Hồ Chí Minh City Airport). As fighting across the blockade lines increased, French commanders finally organized a major ground offensive on February 24, 1861, with three thousand troops plus reinforcements coming from French and Spanish ships anchored in the river. Over three hundred European soldiers died in two days of fighting, along with an estimated one thousand Vietnamese. Two years after the initial battle at Gia Ðịnh, France had won its first military victory against the Vietnamese on terra firma.3

The victory, however, did not signal a turning point in the conquest nor an abandonment of the protection afforded by the waters. Paulin Vial, a frigate captain who served during the conquest and wrote a history of it in 1874, reported that after the victory at Chí Hoà Admiral Bonard withdrew officers from forts built on the Mekong River to consolidate control of the Sài Gòn waterfront. Vietnamese military commanders fleeing Sài Gòn thus took the opportunity to seize the French forts and camps on the Mekong, especially the property of colonial collaborators.4 For another year and a half, the French focused on building the port and city around Sài Gòn while Vietnamese commanders such as TrưƠng Công Ðịnh built new camps in such Mekong towns as Gò Công and at the Nguyễn-era barracks (dinh) at Vĩnh Long (map 5). A peace treaty unexpectedly proffered by King Tự Ðức in June 1862 suddenly halted this new reorganization of authority and splintered the Vietnamese resistance. Phan Thanh Giản, the highest-ranking Nguyễn official in the delta, left for France to continue negotiations on the treaty for the king, but Nguyễn military commanders such as Trương Công Ðịnh rejected it outright and organized guerrilla attacks on French outposts on Sài Gòn's southern frontier at Tân An and Mỹ Tho.

The next five years of colonial conquest and Vietnamese resistance repeatedly tested the limits of French authority in battles fought at watery border zones where deep, navigable streams gave way to shallow creeks and swamps. The swamps around Sài Gòn, the immense Đồng Tháp, and the eastern coastal regions around Gò Công absorbed rebel factions of the Nguyễn army that launched repeated assaults on colonial forts built at the edges of navigable waterways and roads. One unit under Ðịnh attacked a French fort at Nhiêu Thuộc near Mỹ Tho. While only a handful of colonial troops were killed, French fears about more attacks set off a massive naval operation against Ðịnh. On February 25, 1863, about twenty French and Spanish ships blocked the deeper creeks and rivers draining from Gò Công, where Ðịnh was believed to have his headquarters. A floating hospital was anchored in one of the creeks while earthen batteries were built across others to support additional artillery besides that on board the vessels. The Spanish corvette Circé waited in Soai Rạp Inlet while eight French gunboats anchored in other tidal creeks as far inland as they could travel without running aground. The ground forces that carried out the attack from these floating assault platforms consisted of half of a battalion of Algerian tirailleurs (light infantry) garrisoned at Shanghai and a battalion of Filipino soldiers raised by the Spanish (still partners with the French in the colonial conquest) from Manila. In the onslaught of this invasion, Ðịnh's forces scattered, abandoning uniforms and regrouping in other marshes.5 Admiral Bonard used the victory to pressure King Tự Ðức to honor the terms of the 1862 treaty when the signed version returned from Paris. TrưƠng Công Ðịnh escaped and continued to lead small ambushes until 1864, when a junior lieutenant betrayed him to the French.

Other Vietnamese continued to fight, retreating ever deeper into the delta's wild interiors as French forces tightened their control on waterways close to Sài Gòn. Some of the most notable include Võ Duy Dương, who led operations in the Đồng Tháp until 1866; Nguyễn Trung Trực, who had a base of support in the lower delta region around Rạch Giá until 1868; and Trần Văn Thành, who led a millenarian Buddhist sect and organized a network of separatist communities along the Vĩnh Tế Canal from 1868 to 1874.6 Each rebel movement differed, but they all followed a similar logic with regard to the water environment, retreating far from navigable channels into the swamps. Võ Duy Dương, a wealthy landlord before 1862, led over a thousand soldiers from among his tenants and built a base on Tower Hill (Gò Tháp), the ancient sand hill in the center of Đồng Tháp (see map 5).7 Two overland tracks, navigable for a month or two at the end of the dry season, connected the fort to distant villages; most people reached it by sampan. Dương's forces hid there, and by night they solicited money and food from communities on the edge of the marsh. During the rainy season from April to November 1865, they raided more French forts on the edge of the swamps in attempts to foment a general insurrection. The French waited for the water to recede in the winter before launching a ground-based assault in April. This time Europeans fought alongside a newly trained force of several hundred Vietnamese soldiers who followed an ambitious local collaborator, Trần Bá Lộc. Not only the close combat but the mud, leeches, mosquitoes, and sun took a heavy toll on the Europeans, leaving over one hundred dead. After seven days, however, the native militia finally captured Tower Hill, scoring an important victory over the rebels in the delta's largest swamp.8

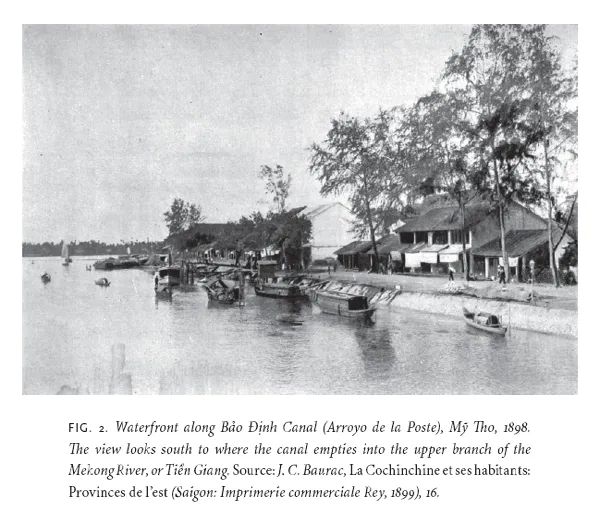

Nguyễn Trung Trực's campaigns from 1862 to 1868 moved the center of anticolonialism farther south into the lower delta (Hậu Giang) as the French expanded naval operations there after 1862. Trực, a locally born fisherman, masterminded an attack that blew up a three-mast French warship anchored on the Bến Lức River some twenty kilometers from Sài Gòn at an important water junction with the Arroyo de la Poste (Bảo Ðịnh Canal), which was the only inland waterway at the time conveying boat traffic from Sài Gòn to the delta.9 Trực's destruction of the warship brought him immediate fame as a popular hero. King Tự Ðức bestowed upon him the honorific title sergeant major (quản cơ), and he and several hundred followers fled from the fighting to establish bases in the lower delta region near Rạch Giá. After six years of evading French troops and watching the French gain control over former Vietnamese outposts in the lower delta, he led a last-ditch attack in June 1868 on the newly completed colonial provincial headquarters in Rạch Giá (map 5). After killing the Europeans sleeping inside, the group fled to Phú Quốc Island. French units caught up with them there, captured Trực, and brought him to the Central Prison in Sài Gòn, where he was executed on October 27, 1868.10

Dương's defeat and Trực's execution caused another leader of the era, Trần Văn Thành, to build a base in the remote border area around Vĩnh Tế Canal. Thành was a priest who led a millenarian Buddhist sect that had grown up in the region since 1847. A charismatic monk, Ðoàn Minh Huyền, preached here and offered healing amulets during a devastating cholera epidemic in 1849, gained a strong local following, and declared himself an incarnation of the Buddha. His millenarian interpretation of Buddhist folk religion blended Khmer and Vietnamese practices with magical incantations and folk interpretations of Buddhist scripture. Thành, a sergeant major serving in the Nguyễn army, converted to the religion after staying at the Temple of Western Peace with Huyền and quickly rose to prominence in the sect.11 Following Huyền's death in 1856, Thành and his wife led the sect, founding new settlements in the interior region east of Vĩnh Tế Canal in the years before the French conquest began. In later fighting with French forces, Thành served under Ðịnh until 1864 and under Dương until 1866 before attempting to contact Trực in 1867. After Trực's capture in 1868, he returned to the settlements he and his wife had founded and led the sect's followers into a dense, swampy forest called Bảy Thưa (map 5). There they built a new community that was both anticolonial and religious in its inception. They dug canals to bring in freshwater and allow communication with outside settlements. In her study of Hòa Hảo Buddhism and millenarian politics, Huê Tâm Hồ Tai explains that, unlike other rebels, Thành's successful evasion of French authorities for six more years was largely due to his appeal as a sect leader, and that it was he who joined the cause of millenarianism with anticolonialism in the region.12

The appeal of the millenarian tradition in this region, however, was due not only to frontier politics but also to the devastation that another recent arrival, cholera, brought by water. Canal projects and new settlements involved thousands of people working in muddy basins with stagnant pools of wastewater. Cholera epidemics swept the region repeatedly in the nineteenth century and killed up to half of all people exposed to it. Just one infected body, if it touched the water, could infect thousands. During the colonial conquest, the carnage of military engagements was combined with the even greater devastation wrought by cholera. Tens of thousands of corpses lined the dry roads, stacked up to be cremated in huge pyres, given the shortage of dry land. Such sights must have caused many peasants to believe that the final days were at hand and that a Buddhist maitreya would soon arrive as had been prophesied. Even after Thành's death in 1873, his followers continued to attract new adepts, especially the laborers conscripted to excavate French waterways such as Chợ Gạo Canal (1876–77).13 They wore amulets inscribed with the four characters “Bưu Sơn Kỷ Hương” and recited secret incantations to receive magical protection from epidemics.

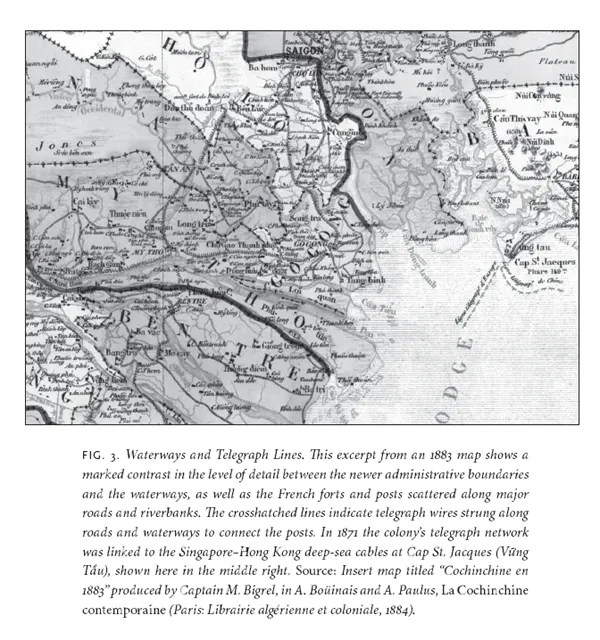

The French conquest of Cochinchina was intensely oriented to movement on the water. The first maps published widely for European audiences in the 1880s reflect this; in one such map, the outlines of the new colony are represented by hatched lines that flow in broad curves across blank terrain, while the branching network of creeks, rivers, and canals is drawn in fine detail (fig. 3). Based on his work on maps in Siam, Thongchai Winichakul suggests that maps facilitated modern imaginings of colonialera states as geo-bodies formed from the outline of political borders. If we imagine such a geo-body for Cochinchina, we see that Cochinchina followed a very different trajectory from most places in Southeast Asia. Surveys of Cochinchina's political boundary and the tedious work of placing boundary markers on territory often submerged under floods began several decades after the initial mapping of its underwater terrain. Even well into the twentieth century, miền tây (Cochinchina's western, or delta, region) was not typically represented as a sovereign region but as a sovereign topology, one measured by hydrographic engineers such as Jacques Rénaud and then patrolled by gunboats and police.14

Colonial maps of Cochinchina in the 1880s included another interesting set of lines: a network of lines with crosshatchings indicating about one thousand kilometers of low-grade telegraph wires strung along the waterways to connect Sài Gòn to the forts and administrative centers established in the delta (see fig. 3). French naval units attached the wires to trees and poles beginning in 1863, and across the immense branches of the Mekong they used more expensive underwater cable, insulated with gutta-percha, an important colonial commodity first discovered in island Southeast Asia. Telegraph lines rapidly compressed the space of this frequently inundated, impassable colonial topology, allowing telegraph operators to send warnings from one fort to another about pending attacks or other events.15 One line led out to sea at Cap St. Jacques (Vững Tầu), where in 1871 it joined the Hong Kong and Singapore trunk lines operated by Sir John Pender's Cable and Wireless Company. This connection further extended France's administrative reach by allowing rapid communication between Paris and the colony.16

Colonial Alterations to the Water Landscape

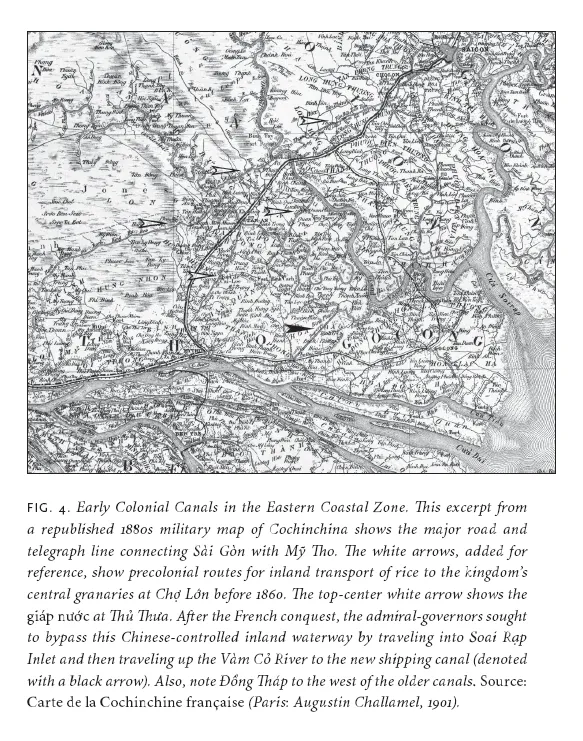

While telegraphs may have compressed the space of communication between the delta and Sài Gòn, Cochinchina's early governors nevertheless focused on the need to build new inland waterways that would allow their gunboats to respond more quickly to uprisings in the swamps. In 1875 Admiral Victor-Auguste Duperré set out to build a new network of inland waterways that would convey deep-draft French ships to major river ports without requiring them to navigate the delta's shoal-ridden inlets. The only existing routes from Sài Gòn to the delta were several waterways first established in the 1700s that reached east from Chợ Lớn via the Bến Lức River to the Bà Bèo Canal or to the Bảo Ðịnh Canal (ca. 1816). However, these shallow, crowded waterways were thronged with boats transporting rice to Chợ Lớn, and they did not permit even the smallest gunboats to pass in all conditions (fig. 4). With new funds from Paris and an army of conscripted laborers, the Department of Public Works (DPW) commenced digging (by hand) seven new projects intended to facilitate ship traffic through the Eastern Coastal Zone.17 Each was roughly one hundred meters wide and five or six meters deep. French engineers such as Rénaud, educated at the elite École des ponts et chausées, planned these canals much the same way that they planned roads. The large projects were to form a backbone for navigation from which narrower, secondary canals would then branch off. From these secondary canals, tertiary canals just wide enough for two boats to pass would connect individual hamlets.

Of the colonial projects, Chợ Gạo, or Duperré, Canal was by far the most important and expensive for the colony. It connected Sài Gòn to the nearest delta port, Mỹ Tho. Mỹ Tho was the largest town in the delta at the time, expanded largely via the commerce generated from ethnic-Chinese enterprises. From this embarkation point, steamboats carried passengers, mail, and cargo across the rivers to other delta towns and upstream to Phnom Penh. Once completed, Chợ Gạo Canal reduced trave...