![]()

PART I Beginnings

![]()

1 • THE FORMATION OF SEATTLE CORE

As the nation, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, watched nightly TV coverage of the struggle for civil rights in the South, we saw the vicious treatment of black people who asserted their rights as Americans. We saw people walking in Montgomery, Alabama, for a year in 1955–56 until they could get fair seating on the buses. We saw bayonets drawn against black high school students in Little Rock, Arkansas, in September 1957. We saw black college students denied service at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960. Inspired by their example, disciplined students in seventy-eight cities sat-in at legally segregated lunch counters. Students endured assaults by angry whites who ground mustard into their hair or put lighted cigarettes down their backs. In May 1961 in the first wave of Freedom Riders, John Lewis (now a member of Congress) and Albert Bigelow were badly beaten as they left the bus in Rock Hill, South Carolina. In Anniston, Alabama, NBC and CBS showed vivid film clips of the burning of the same Freedom Riders’ Greyhound bus. Its occupants, both whites and Negroes, were assaulted with sticks and bats. We saw the vicious and violent attack by a Ku Klux Klan mob of two hundred against passengers who were simply testing their legal right to integrated service in the Trailways bus station in Birmingham, Alabama.

Shocking events happened almost every day. Who could stand idly by? Even in the northwest corner of America we heard the call for action and a plea to join the Freedom Riders, to fill the jails, to work to end the violence and to end segregation.

One evening in May 1961 four white strangers met by chance after a performance of Lorraine Hansberry’s play Raisin in the Sun at the Cirque Playhouse in the Madrona neighborhood of Seattle. Ken Rose, Ray Cooper, and Joan and Ed Singler were drawn together to talk about the moving performance. They were stirred by the play’s message of both the destruction of human dignity and the hope for the future. After the show they went backstage to talk with the actors, including Norman Johnson, who had performed the role of George Murchison. The conversation led from discussing the play to sharing deep concerns about the violence in Alabama and Mississippi and the segregation experienced in Seattle. They were fast becoming friends. The thoughts and passionate feelings that surfaced in that conversation made them aware that something had to be done. They agreed that they needed to meet soon.

Ken Rose was an articulate nineteen-year-old student of political theory at the University of Washington and an active member of the Liberal Religious Youth at the University Unitarian Church. His friend Ray Cooper, two years out of high school, lived in the University District. Ray realized that he could not sit idly by engaging in coffee house discussions about art while people were being brutalized in the South. Ed and Joan Singler were in their late twenties. Ed, from Detroit and the son of union organizers, had many encounters with discrimination while traveling with his best friend from law school, who was black and lived in an integrated neighborhood. Joan, whose parents were community volunteers, was aware of how much just one or two committed people could accomplish. She was also active in the unions. She had recently returned from Pasco, Washington, where she had been appalled at what looked to her like a southern ghetto. Norman Johnson, a draftsman for Boeing, frequently experienced police harassment as he traveled to his job assignment at the Applied Physics Lab in a “white” part of town, being stopped and questioned, especially after dark or if he was carrying his black gym bag.

These five people from diverse backgrounds and experience were drawn together by a commitment to correcting racial injustice. They met a few days after the play at Norm Johnson’s home on Superior Avenue in the Leschi neighborhood. That evening Norm Johnson, Ken Rose, Ray Cooper, Joan and Ed Singler, along with Carl Jordan, one of Norm’s roommates who joined the conversation, took the first step in answering CORE’s call for national action. Ray, in spite of concerns for his personal safety—how many more Freedom Riders would be beaten?—had decided to join others responding to urgent requests by National CORE to participate in the Freedom Rides to Mississippi. What he needed now was financial help. Ray’s willingness to join any activity taking place in Mississippi came as a shock to Bob Anderson, Norm’s other roommate. Having grown up in Naches, Mississippi, Bob knew all too well the conditions and intimidation that black people had to face every day just to live. “Why,” he asked “would anyone go there voluntarily and put themselves at risk of bodily harm?”1 Ray listened to Bob’s comments but was not deterred, nor were the rest of us in the group, who committed ourselves to raising the money to send Ray to Mississippi. If we had understood how lawlessly the Klan and white supremacy groups operated in Mississippi, sometimes with the cooperation of a sheriff, we might have been more cautious.

Nationally, CORE was at the forefront of volunteer militant action against discrimination. Since the little group’s first commitment involved sending Ray off to be a CORE Freedom Rider, the obvious way to organize in Seattle was to join the Congress of Racial Equality. In June 1961 the Seattle chapter of CORE was born.

PRIOR CIVIL RIGHTS EFFORTS IN SEATTLE

Although it is true that the founding of Seattle CORE was the result of a chance meeting of five people, the immediate infusion of a cadre of people who were already seasoned supporters of civil rights soon filled the ranks of dedicated CORE members and contributed greatly to our early successes.

In 1957 Don Matson, Walt Hundley, Ivan King, Ray Williams, and others had tried to form a CORE group in Seattle but were not able to rally enough supporters to establish a chapter or take on an action project.2 Many of them were members of Church of the People, where socialist ideals and people of color were welcome. With a congregation that included many interracial couples, the church experienced as much discrimination, if not more, than individual blacks. As sometimes happens in intense groups, the congregation split over differences of religious and political ideology, and these CORE pioneers moved on to become members of the University Unitarian Church.3

Don Matson, an invaluable white member of Seattle CORE, brought his organizing skills and leadership in the Unitarians for Social Justice to bear on his activism in CORE. Unitarians for Social Justice organized a subcommittee devoted to integration. Small in number but extremely active and led by Don Matson, the committee included Doris Eason, Jean Jones, Mary Barton, and John Cornethan.4 By July 1961 all these people, plus other members of the congregation, were either active members of CORE or supported CORE projects.

So with the help and support of the Unitarians’ Integration Committee, the Unitarians’ Liberal Religious Youth, university staff and faculty responding to notices placed on campus, and members of the black community, CORE took off. Ray Williams, an African American, became the first chairman of Seattle CORE.

FREEDOM RIDERS

Before Seattle CORE held its first organizing meeting, Seattle’s Freedom Rider was on his way south. Contributions paid for his airline ticket, and Ray Cooper flew to Los Angeles, where there was an established CORE chapter. On July 12, 1961, along with other young people, Ray then headed east to New Orleans for training. Most of those in the civil rights movement used Gandhian nonviolent passive resistance as a discipline and a response to violence and hatred. Volunteers participating in the Freedom Rides accepted nonviolence as a tactic, accepted the possibility that they might be physically attacked, and practiced not striking back.

Once their training was complete the Freedom Riders boarded a Greyhound bus headed to Jackson, Mississippi, to challenge the segregated facilities at the interstate bus station. When Ray Cooper and his fellow Freedom Riders stepped off the bus in Jackson, they were immediately arrested and sent to Hinds County Jail. Earlier Freedom Riders had already filled the county jail, so Ray and the riders with him were then sent to prison at Parchman Farm Penitentiary in Parchman, Mississippi. Ray spent forty-seven days, and lost twenty pounds, in what he describes as “Hell’s Kitchen” before being arraigned and given a court date in March 1962. After his release from prison Ray spent some days meeting the black residents of Jackson before he boarded another bus to return to New Orleans. The return trip seemed equally dangerous for the Freedom Riders. The Mississippi State Patrol and members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) followed the bus and intimidated the returning Freedom Riders.5

That fall Ray returned to Seattle to be an active member of Seattle CORE. He remembers leaving a small, mostly white group of civil rights activists and returning in just a few months to find a fully integrated chapter of CORE. In 1963 he was one of twenty-one young people who sat-in at the Seattle City Council chambers, protesting city officials’ inaction on the issue of segregated housing.

Shortly after Ray left Seattle for the South, Widjonarko Tjokroadismarto, an exchange student from Indonesia and a graduate student at the university, participated in the Freedom Rides. As reported in the August 3, 1961, issue of the University of Washington Daily, his motivation was “to stay for a few weeks in Jackson to study segregation problems in the South.” (Having never been to the South, his plan for a two-week stay was somewhat naïve and at odds with what the Jackson City officials had in mind for Freedom Riders.) Widjo, as he was known on campus, was the son of an Indonesian diplomat. Because of diplomatic immunity his plan never got off the ground. When he arrived at the bus station in Jackson with a group of Freedom Riders from New York, two detectives forcibly removed him from the bus station’s Negro waiting room. The Daily went on to report, “Widjo said he gave up plans to file suit against the detectives.” What he did do, however, was to speak out about his experiences at several showings of the film Freedom Ride sponsored by Seattle CORE.

A third person from Seattle, Jon Schaefer, raised in the all-white gated community of Broadmoor, answered the call for national engagement in the struggle for civil rights and joined the Freedom Riders. A member of CORE, Jon was sponsored by the Unitarians for Social Justice and given some financial help by Seattle CORE. Schaefer became part of a Freedom Ride and received the same “Southern reception and hospitality” and served the same jail time as Ray Cooper did. Jon, however, stayed in the South and became involved in Freedom Highways, a project protesting discrimination at Holiday Inns and Howard Johnson’s Restaurants along U.S. highways in the South. His protest took place at a Howard Johnson Restaurant in North Carolina. Jon, a Caucasian, and four Negro young women waited but were never admitted into the restaurant, so they sat-in in the doorway. For refusing to leave they were arrested and each served a thirty-day prison term, for Jon his second incarceration. Finally, after Jon’s release, he was asked to join the staff of National CORE and worked as a field secretary in the North and East.6

SEATTLE CORE TAKES OFF

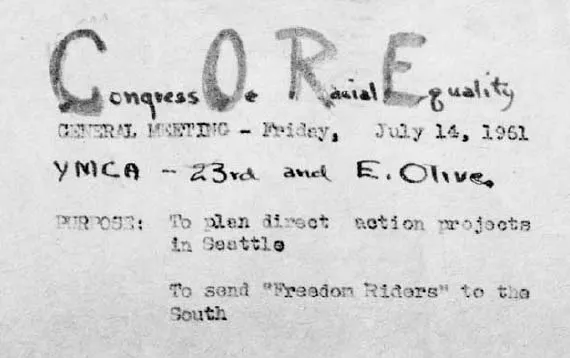

How to change “segregated Seattle” and raise bail money for Ray Cooper and Jon Schaefer became Seattle CORE’s challenge. To reach other people outraged about the injustice and violence in the South we sent out a three-cent-postcard announcement of an organizing meeting. This notice listed our purpose “to plan direct action projects in Seattle” and “to send Freedom Riders to the South.” We assumed that those who received the mailing knew about CORE and the Freedom Rides taking place in the South. If they did not, perhaps they would come anyway. The meeting was scheduled for July 14, 1961, at the YMCA at Twenty-Third and East Olive. Our mailing list (perhaps based on Christian Friends for Racial Equality members) was quite small, so we placed ads in the black newspaper, The Facts, and in the student newspaper at the University of Washington, The Daily. We also posted notices in black churches, which led to a number of black parishioners becoming early members of CORE. Ministers and parishioners of many congregations became very involved and proved to be among the strongest supporters of Seattle CORE.

Ken Rose, CORE’s organizing secretary, placed a notice for the July 14 CORE organizing meeting at the University Unitarian Church and at other sites on the campus of the University of Washington. The notices on campus attracted faculty and staff, including Si Ottenberg, of the Anthropology Department, and his wife, Phoebe; Larry Northwood, of the School of Social Work, and his wife, Olga; and Richard Morrill, of the Geography Department, and his wife, Margie, who were also Unitarians. They all became active members of CORE. From those who attended that first meeting on July 14, a cadre of people emerged who were committed to ending discrimination in Seattle and spent intense weeks, months, and years trying to attain this goal.7

Postcard announcement of initial CORE organizing meeting. (CORE, Matson Collection)

After the July 14 meeting we approached the NAACP and the Baptist Ministers Alliance to request their cooperation and support. Although the NAACP was recognized as the organization working on behalf of African Americans nationwide, its major thrust at this time was initiating lawsuits and providing legal counsel for the many demonstrators being jailed in the South. CORE would use more direct action. Locally, the NAACP had attempted to change segregated housing patterns and discriminatory hiring practices, negotiating with Safeway in the late 1940s for a few jobs for Negroes and proposing a city open-housing ordinance in 1961 with no success. To support student lunch counter sit-ins in the South, the Seattle NAACP organized picketing at the downtown Woolworth. Joan and Ed Singler and Ma...