![]()

![]()

1 / WHY A WILDERNESS ACT?

Howard Zahniser carried a heavy burden the last eight years of his life. It was not just that he was the executive director of the Wilderness Society, the chief author of the Wilderness Act, and the legislation's most faithful champion. It was his coat. Zahniser had two long overcoats into which extra pockets had been sewn that he filled with copies of wilderness legislation, maps of the public lands, transcripts of congressional testimony, the writings of Thoreau, and more. He was a walking library, ready to educate the nation about wilderness, one person at a time. As he saw it, everyone should be in favor of wilderness. Who could oppose protecting the nation's heritage? Those who opposed the legislation, he believed, did not object to wilderness in principle; they misunderstood the particulars of the proposed law. The only way to fix that problem was to listen to their concerns, explain the aims of the legislation to them, and convince them of the reasonableness and importance of the Wilderness Act to the American people.

Zahniser had long been enamored of wilderness. He spent his youth exploring the Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania near his hometown of Tionesta. He and his wife, Alice, honeymooned in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. And during much of his life, he and his family found retreat at a family cabin in the Adirondacks. He did not look the part of a wilderness champion. He was a bookish man, slightly round, who wore owlish eyeglasses and had an imposing forehead. He was often busy with correspondence or had his nose buried in a book or manuscript. But he reveled in wilderness, in language, and in his family. Zahniser was idealistic, but practical, and his commitment to both the values of wilderness and the political process made him a persistent and effective advocate for the nation's wild lands. The magic of Zahniser's wilderness advocacy lay in his patriotism and spirituality, his faith in the government and the political system, his commitment to the values of wilderness, and, as his biographer Mark Harvey explained, “his essential decency and the unfailing respect with which he treated everyone he encountered.” Drawing on those beliefs and values, Zahniser played a pivotal role in shaping the campaign for the Wilderness Act of 1964.1

The work of Zahniser, the Wilderness Society, and the national coalition that championed the creation of the National Wilderness Preservation System has assumed symbolic importance in American environmental history. The New York Times editorialized that the legislation was a “landmark,” and later historians have affirmed that assessment. One historian described the new “appreciation of wilderness [as] one of the most remarkable intellectual revolutions in the history of human thought about the land.”2 The Wilderness Act is often regarded as the culmination of a campaign that began with people such as John Muir and Theodore Roosevelt. The Wilderness Act succeeded not just because it was rooted in long-standing concerns for conservation and preservation, however, but also because it aligned with the political priorities important to mainstream American liberalism in the early 1960s. It was one of many laws passed during Lyndon Johnson's Great Society that invested the government with responsibility for protecting the public interest in a clean and healthy environment and established the foundations for the American environmental regulatory state.

This confidence that the Wilderness Act met a public interest propelled Zahniser, his allies, and the legislation forward. “We are advocating a program for the people of the United States of America,” explained Zahniser. “The significance may not be how far we can move with [the Wilderness Act] but in the fact that so many people take that step.”3 It is tempting to dismiss such rhetoric as political posturing and to assume that the legislation was of significance only to a fraction of Americans—nature lovers, scientists, and those who tromped in the nation's wilderness—but that does not explain why the legislation commanded such broad political support. When the Wilderness Act became law in 1964, the Senate approved it 73 to 12 and the House approved it 373 to 1. Its congressional champions included leading Democrats and Republicans, and its coalition of supporters included not just the national and local conservation organizations, but also the General Federation of Women's Clubs, the American Planning and Civic Association, and the AFL-CIO, the nation's leading labor organization. Knowing how environmental reform has often been paralyzed by partisan politics since the 1980s, it is worth considering how the Wilderness Act galvanized such a broad constituency in the 1960s. The campaign was not won with careful research briefs on the state of the nation's timber or petroleum supply or the diversity of wildlife in wilderness. Instead, it appealed to national values—patriotism, spirituality, outdoor recreation, and a respect for nature—and the responsibility of the people and the government to protect them. In its aims, its rationale, and its compromises, the Wilderness Act reflected a pragmatic political formula that laid the foundations for what has become an expansive wilderness system. That success offers clues to the political origins of an environmental movement that came to be a powerful force in American politics.

The Threat to the “Public” Lands

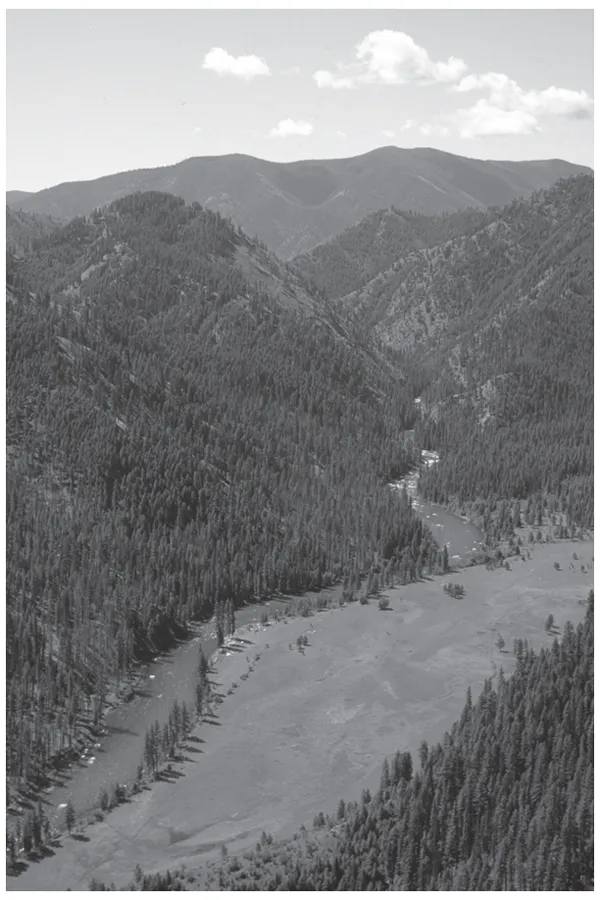

The story of the modern wilderness movement begins with how the public lands became “public.” Consider headlines such as these: “Bush Is Asked to Ban Oil Drilling in Arctic Refuge.” “Tempers Rise over Desert Conservation.” “U.S. Judge Upholds Clinton Plan to Manage Northwest Forests.” “Feuds with Feds Make West Wild.” “Obama to Sign Major Public-Lands Bill.”4 Behind these headlines is a basic assumption: the American people have a vested interest in the future of the nation's public lands. Remember Woody Guthrie's refrain: “This land was made for you and me.” That the public lands are “public” is a contested claim, however.5 What are now the “public” lands could have been dispensed with or managed in other ways. Native Americans, for example, could have been given a larger share of their homelands. In the late nineteenth century, at the same time the federal government established national parks and forests, it pushed Native Americans in the West off their homelands and onto reservations.6 Congress could have given the western states more of the land within their borders when they entered the union. In many western states, however, the federal government remains the largest landholder, which is a point of frustration in states such as Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, where the federal government owns 86 percent, 64 percent, and 49 percent of the land.7 The public lands also could have been managed by the federal government with little involvement of citizens, industry, or other organizations. At the heart of the wilderness movement was the basic assertion that all Americans have a stake in the future of the nation's public lands.

What are now considered to be the “public” lands are the legacy of the nation's conquest of the American West. Between 1803 and 1867, the United States staked firm claims to much of the nation's western territory that now makes up the United States of America. Significant events in that expansion included President Thomas Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and Secretary of the Interior William Seward's acquisition of Alaska in 1867. Those agreements meant little without the will to back them up with force. By the end of the nineteenth century, by treaty, purchase, and conquest, the United States had defended its claims from Europeans, wrested California and the Southwest from Mexico, and marginalized Native Americans. Then, in the mid-nineteenth century, Congress began giving those lands away. Westward-moving settlers were given 160-acre parcels of land under the Homestead Act, with Jeffersonian hopes of fostering a nation of independent farmers. Railroads and speculators made off with tracts of land best measured in hundreds of square miles. Loggers, miners, and cattle ranchers moved west, too. Loggers began felling the forests of the Great Lakes, Pacific Northwest, and the northern California coast. Mining companies staked claims to gold, silver, and copper lodes across the West. And cattle ranchers began to run their herds, and soon their fences, on lands that a generation before had been home to herds of buffalo and nomadic Indians.

Although such policies helped integrate the West into the United States—by encouraging settlement and the building of railroads and reducing the threat of Native Americans and foreign powers—some observers began to worry that such policies were shortsighted. Instead of supporting a nation of yeoman farmers, the government's policies seemed to encourage the exploitation of the nation's natural resources: the slaughter of the bison on the Great Plains, the clear-cutting of forests in the Great Lakes, and destructive mining practices, such as the hydraulic mining that followed the California Gold Rush. George Perkins Marsh, an early conservationist, was among the first to warn that while America had been blessed with extraordinary natural resources—minerals, forests, and waterways—such riches were not limitless. John Muir, who helped found the Sierra Club, echoed such concerns in 1897. He warned that although God had long saved these lands from “drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods…he cannot save them from fools,—only Uncle Sam can do that.”8 Some westerners also began to realize that they needed the government to protect the mountains that supplied their cities with water and to oversee the grazing lands they depended on for their cattle and sheep. As America became an increasingly urban nation, dominated by growing cities such as New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, some Americans began to worry that the nation was losing touch with the wilderness from which the nation's institutions had been forged.9

At the turn of the twentieth century, the federal government began to take new responsibility for managing the western lands. Drawing on these many concerns—materialistic, romantic, and nationalistic—a group of prominent Americans, among whom president Theodore Roosevelt, Forest Service chief Gifford Pinchot, and John Muir are best remembered, advocated placing a portion of the nation's lands in permanent government ownership—a policy shift that meshed with a new commitment to a strong federal government during the Progressive era.10 Consequently, Congress began to establish what eventually became four federal land agencies: the Forest Service (1905), the National Park Service (1916), the Fish and Wildlife Service (1940), and the Bureau of Land Management (1946). Starting in the 1910s, the federal government also began to purchase logged and mined lands in the East; some of those lands became national forests and others became national parks such as Shenandoah in Virginia and the Great Smokies in North Carolina and Tennessee. Thus, by the 1950s, the federal government still oversaw about one-third of the nation's land—some of it in the East, more of it in the West, and much of it in Alaska. These were the federally owned public lands, and the four federal land agencies were charged with managing those lands in the public interest.11 The nation has been debating what that meant ever since.

After World War II, that debate gained new urgency as the nation's economy and western settlement accelerated. Historians have described the 1950s as the “supreme period of development” for western resource industries, such as mining, lumber, and energy—what scholars have described as the industries of the “Old West.”12 Bernard DeVoto, an iconoclastic historian and columnist, described the American West of those years in a different way. He called it “the plundered province.” Writing for Harper's Magazine, DeVoto warned Americans that special interests in the West were raiding the nation's public lands for their own private benefit—they were overrunning the public lands with cattle, planning to build dams on scenic rivers, and calling for logging in the national parks. Whose land was he talking about? DeVoto did not mince words: “This is your land we are talking about.”13 It was a new way of looking at the western lands. DeVoto, like a growing number of conservationists, worried that the federal land agencies were more likely to manage the western lands in accordance with local wishes, which usually gave priority to economic development activities, than with national concerns, which he believed gave more attention to long-term protection of the land. For wilderness advocates, DeVoto's central argument came to define postwar debates over the public lands. The nation's public domain did not belong to resource industries, federal land agencies, or western states. Instead, the public lands were a national heritage in which all Americans had an interest and should have a say.

DeVoto's claims upset many westerners. While the West's industries and politicians often acted as if the public lands were most important as a resource for the region's economy, many westerners also cared passionately for the western landscape. Hunting and fishing were important pastimes, and some saw wilderness as a way to protect their favorite hunting grounds. Rod and gun clubs, sporting groups, and hiking and saddle clubs all provided important support for protecting the public lands in the 1950s and 1960s.14 For instance, Michael McCloskey, who led the Sierra Club between 1969 and 1985, got his start organizing horsepackers in rural western Colorado in support of the Wilderness Act in 1963.15 Those who lived in the urban West were more likely to agree with DeVoto's claims. Since the end of World War II, metropolitan areas around Seattle, Phoenix, and San Francisco had grown rapidly, as workers moved west to work in new industries, such as technology and defense.16 Unlike the industries of the “Old West,” which relied on natural resources, these new industries represented what scholars later described as the “New West,” which valued the public lands for recreation and tourism more than for natural resources.17 Thus, while many interests and industries in the West remained committed to developing the public lands, many westerners also wished to see them protected. The West, whether “old” or “new,” has had a conflicted relationship with the public lands.18

The controversy over the future of the West and the public lands converged dramatically in northwest Colorado in the 1950s. The federal government announced plans for ten new dams to reengineer the upper Colorado River watershed to provide flood control, irrigation water, and electricity to the growing Rocky Mountain West. Such plans were representative of many large-scale projects the federal government undertook in the 1940s and 1950s that accelerated the region's postwar development. But one of the proposed dams was slated for Echo Park, a remote canyon located inside Dinosaur National Monument. Wilderness advocates worked to block the proposal for six years. And, as a half century before, when the government proposed a controversial dam at Hetch Hetchy in Yosemite National Park, the threat to Echo Park thrust the future of the nation's public lands into the national spotlight. With the leadership of two young and rising environmental leaders—the brash and spirited David Brower of the Sierra Club and the steadfast and eloquent Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society—two small organizations led what became a national campaign that rallied conservation organizations in coordinated action to stop the dam and maintain the integrity of the park system. Notably, the conservationists did not oppose all dams on the Colorado, only a dam within the boundaries of the park system. Over the strenuous objections of lawmakers from the Rocky Mountain West, the wilderness movement succeeded in persuading Congress to remove the Echo Park dam from the project in 1956. It was a telling victory. While wilderness advocates failed to stop the dam in Yosemite National Park in 1913, they were able to stop the dam in Echo Park in 1956. That turnabout suggested the growing political might of an organized wilderness movement and the claim that these were, in fact, lands of national importance.19

Echo Park taught wilderness advocates two lessons, one old and one new. The old lesson they had learned many times before across the West, at places such as Three Sisters Primitive Area in Oregon, the Upper Selway in Idaho, and Olympic National Park in Washington. All of those places were ostensibly protected as “wilderness” or parks by the federal land agencies. But as the postwar western economy boomed, the Forest Service and Park Service were increasingly willing to open wild areas for development, tourism, and the interests of local communities.20 Those who cared about wilderness were constantly fighting a los...