![]()

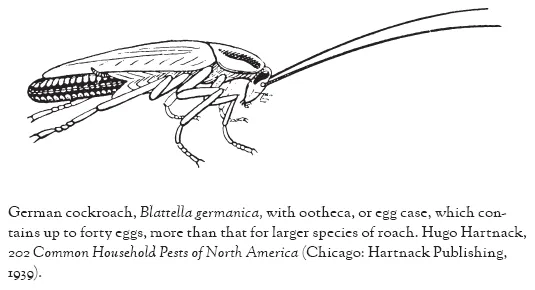

PART ONE

THE PROMISES OF MODERN PEST CONTROL

MANY URBAN HOMES AND NEIGHBORHOODS IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE twentieth century teemed with pests. During surveys of Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1908, entomologists sometimes caught over two thousand houseflies with a single sheet of flypaper hung for two days in a residential area. At least half of residents entering Chicago Housing Authority projects in 1938 had lived with bedbugs in their old homes. One mortified New Yorker, writing in 1921, estimated that her exterminator removed thousands of German cockroaches from her kitchen—a not-unusual yield for her city just after the Great War. In the mid-1940s, ecologists in Baltimore found many central-city blocks that were home to two hundred rats each, with four hundred thousand rats residing in the city overall—and these estimates likely undercounted rats that lived inside houses.1 Such infestations seemed primitive and backward in an era of modern architecture and housing, new domestic technologies, and advanced medical and ecological knowledge.

Urban reformers of many stripes responded to infestations like these by trying to rid city-dwellers' homes of pests, especially homes in low-income communities. Between the blossoming of medical entomology around 1900 through the 1960s, pests became one of many aspects of poor citizens' lives in which health and welfare crusaders intervened. Reformers promised modern living spaces, nearly free from pests, for the poor. Some reformers saw new urban infrastructure and housing as the solution to teeming pests. Rational, efficient sanitation could remove wastes that bred and fed pests from the city. Housing reform programs aimed to solve an array of social and environmental problems by either rehabilitating infested homes or else demolishing them and replacing them with modern, healthy structures that were less vulnerable to pests. Many reformers promoted modern pest control methods to be practiced by citizens or trained exterminators in residents' homes. Some tried to teach women how to make their homes healthy in the midst of the urban environment. Others promoted chemical technologies for controlling pests—sometimes as a magic bullet and sometimes in conjunction with other environmental changes. Pest-control reformers in the first half of the twentieth century placed their faith in the modernization of domestic and urban environments, whether they urged top-down infrastructure and housing projects on the one hand, or practices and technologies applied in the home on the other.

Many reformers failed to see the ways in which pests remained entangled in urban politics and communities amid these modernization and education projects. Only a few advocates for pest control combined sanitation, housing reform, domestic education, or pesticide use and the empowerment of people who struggled daily with pests. Even when campaigns were based on ecological knowledge, reformers often missed the ways in which pests' ecology was communal and political. Attempts to control pests without changing politics recall the words of preservationist John Muir: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”2 Muir's words were inspired by mountain meadows lush with sedges and lupines, but they apply equally to basements and back alleys swarming with rats. Pests were not only “hitched” to physical conditions such as the presence of garbage or house foundations in ill-repair. They also thrived on racial segregation, underfunded housing inspection programs, and cultural stigmas that led residents to try to hide infestations. Modern pest controllers promised to make homes healthy, but many tried to “pick out” pests from complex, enduring social struggles. Some campaigns succeeded despite their lack of social and environmental holism, but in other cases, the pests persisted alongside tenacious inequalities in American cities.

Each of the chapters in part one begins with a composite sketch of pests' life-worlds within one city where that species thrived in the first half of the twentieth century. These sketches are based as much as possible on descriptions of the cities themselves, as well as on contemporary and more recent science about the specific pest. The aim of these sketches is to illustrate the ways these pests encountered urban, domestic environments, and to show how pests sensed and moved through urban landscapes. The chapters end with a similar composite sketch, showing how the environment changed—and didn't change—from the perspective of the pest.3

![]()

1

FLIES

Agents of Interconnection in Progressive Era Cities

As temperatures climbed into the nineties in June 1900, a female Musca domestica buzzed about a small stable in southeastern Washington, D.C. She alit upon a heap of horse manure inside an old wooden bin and deposited 120 eggs under a lump of dung. The young maggots emerged twenty-four hours later and then ate their way into the dung heap for four days. As they grew to their full larval length of about half an inch, they migrated back toward the edges of the pile along with thousands of well-fed cousins. They spun pupae around themselves; inside, they spent four or five more days transforming into adult houseflies. Still, the manure remained in the bin.1

Some ten days after their mother laid them as eggs, the adult houseflies emerged from their pupae and climbed out of the pile. They joined a buzzing cloud of their kin in the tight space between the top of the manure heap and the lid. Some flew through a gap in the lid, but most remained until a man opened the bin to shovel in fresh dung. The hungry swarm burst out of the bin.

One fly flew through an unscreened stable window and a few yards toward a produce cart carrying, among other things, cherries that had begun to ferment during their transit from a farm on the city's outskirts. The fly alit upon a cherry, and the minuscule hairs on her feet, akin to taste buds, sensed a viable meal. She vomited digestive fluids onto the cherry's skin, extended her proboscis with its raspy, liplike lobe, and began to mouth and ingest the cherry as it softened.2 She flitted about the produce cart all day as it made deliveries to markets near the Capitol. Some grocers waved her and the other flies away, but others seemed unconcerned about their presence.

She copulated with a male fly. Garbage pails and dairy trucks nourished her, and the eggs inside her, for five days. Then the fly detected a new scent: a heap of human waste excavated from a privy by a small-time scavenger and dumped illegally in a lot just across the alley.3 The heap's fragrance overpowered that of the horse dung in the street and even that of the block's half-dozen privies. The ammonia odor of urine fermenting on a steamy day not only attracted the fly, its chemical signal also induced oviposition, the deposition of eggs. She nestled into a sheltered area on the side of the mound and, over the course of the next day, laid ten dozen eggs.4 The air above hummed with hundreds of other flies, residues of human feces and urine clinging to the hairs on their feet.

Several flies alit and rested for a moment upon the outside wall of the nearest house. A mix of odors wafted from a window, and several flies found easy passage indoors. Some fed at a garbage pail and a sticky pot in the kitchen. Others circled the head of an infant drinking a bottle of milk, tickling the baby's ears.

IN 1900, THE EMERGING SCIENCE OF MEDICAL ENTOMOLOGY GAVE progressive reformers a troubling new perspective on urban houseflies. Could ubiquitous flies, bred in poorly managed horse manure, pick up germs from privies and human waste dumps? Leland O. Howard, chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Bureau of Entomology, routinely found illegal dumps teeming with flies as he walked the streets of Washington, D.C. He described one dump, left under cover of a steamy night, that by the next day “swarm[ed] with flies in the bright sunlight.” Indoor spaces provided no haven from flies bred outdoors or the germs they might pick up there. Howard observed that “within 30 feet [of the dump] were the open windows and doors of the kitchens of two houses kept by poor people.”5 Flies endangered infants and young children particularly; one educator estimated that over seventy thousand died each year in the United States from fly-borne disease.6

In the first two decades of the twentieth century, many urban reformers feared that houseflies would imperil city-dwellers at home so long as horse manure clogged streets and privies plagued poor neighborhoods. They saw flies as agents of interconnection, linking diseased bodies with healthy ones, delivering pathogens across neighborhoods, and weaving domestic spaces into the city's ecological fabric. Flies flitted from waste heaps to mothers in kitchens, babies in cradles, and families in crowded cottages. Reformers such as Howard pressed for better municipal waste management to protect families in their homes. Housing advocates also saw flies as markers of vice and social dissipation, and demanded sanitary homes for the poor. The first reformers to embrace medical entomology sought public and preventive solutions to the fly menace.

Modernizing manure disposal and replacing slums would require hefty public funding, however, and municipalities failed to make these matters budgetary priorities. Furthermore, some public health experts disputed flies' role in spreading disease; for some, flies in the home simply indicated personal slovenliness, not an immediate health threat. In the absence of support for broad-scale sanitation, welfare advocates and health departments who remained suspicious of flies increasingly called upon citizens to exclude flies from their homes. Health agencies urged families, especially women, to keep flies out of their homes by installing screens and maintaining vigilant watch over the borders of domestic space. Rather than limiting fly-breeding, this strategy required women to separate their homes from the ecology of the city. Urban nature and human culture resisted this separation. When urban fly populations did eventually subside, neither sanitation, housing reform, nor household fly control deserved the most credit. These efforts, though, used flies to justify the assertion of state power to contain citizens as well as insects.

FROM DOMESTIC COMPANION TO SUSPECTED VECTOR

By 1900, Americans had long regarded rats, roaches, and bedbugs as menaces, but popular opinion of houseflies varied. Material and popular culture shows that some nineteenth-century Americans considered flies pests, if not necessarily disease carriers. The song “Shoo Fly, Don't Bother Me,” dating to the Civil War, attests to the nuisance role of flies—and to whites' appropriation of black culture. The white composer T. Brigham Bishop reputedly based the song on a comment overheard in the black company he led, and the song became popular as performed by both black singers and white minstrel groups.7 Housewifery guides provided recipes for housefly poisons, such as cobalt in sugar water. As window and door screens became more available during the late nineteenth century, families who could afford these devices held both mosquitoes and flies at bay, though mosquitoes were more annoying than the nonbiting housefly.8

At the same time, many Americans believed houseflies to be harmless or even entertaining or useful. Some housewifery guides offered recipes for cockroach and bedbug control but none for fly control.9 Children's books portrayed buzzing, flitting flies as benign domestic companions, ideal for piquing infants' curiosity. Flies' habit of washing their faces with their forelegs gave an impression of cleanliness; they also seemed to act as the garbagemen of the insect world as they consumed organic matter.10 For some, the ubiquity of flies in daily life bred amused resignation, as expressed in a popular quip about a customer in a dimly lit restaurant who mistook a custard pie crawling with flies for huckleberry. One entomologist deemed the nineteenth century “the Period of Friendly Tolerance” of houseflies. Another joked that “a few of them were nice things to have around, to make things homelike.”11

Regular Americans varied in their views of houseflies, but a growing number of physicians and naturalists believed they could transmit germs.12 In 1895, George Kober, a respected health officer and Georgetown University dean, surmised that flies might have helped spread typhoid fever bacilli in the nation's capital. Over typhoid's course, patients develop high fevers, rashes, and delirium, and pass germs in infected diarrhea. Typhoid struck cities nearly every summer; Washington's 1895 epidemic sickened at least 800 people and killed 143. Kober blamed most cases on contaminated wells, but some cases appeared in clusters around city blocks with privies and illegal dumps, and at time intervals suggesting a source other than water. Kober attributed these to “the agency of flies,” which “abound wherever surface pollution exists [and] may carry the germs into the houses and contaminate the food or drink.”13 Then, in 1898, during the Spanish-American War, U.S. Army surgeons also proposed that flies carried typhoid germs from primitive privies to mess halls at stateside military camps.14 Camp conditions recalled those in urban neighborhoods lacking sanitary infrastructure.15

Naturalists and health experts subjected houseflies to new scrutiny at the same time as malaria and yellow fever studies focused in on vector species of mosquitoes. Flies lack the piercing mouthparts that let mosquitoes access human bloodstreams for withdrawal or injection of pathogens.16 The housefly's accusers postulated instead that it served as a mechanical vector, carrying microbes on its mouthparts or sticky, hairy feet. Given flies' attraction to fecal matter, gastrointestinal diseases caused the most worry: typhoid, cholera, dysentery, and the deadly annual outbreaks of infantile diarrhea known as “summer complaint.”17 These germs might cling to a fly until they brushed off during a visit to a milk truck, produce stand, or baby bottle.18 Some speculated that flies might also deposit germs in regurgitated fluids or with bits of feces, euphemistically called “specks,” that dotted window panes in infested homes by the thousands.19 Experiments found germs on the feet and mouthparts of flies exposed to infected stools.

Cases of—and deaths from—these diseases peaked in summer, among both adults and young people, precisely when heat hastened flies' reproductive cycle. Growing fly numbers seemed to speed the circulation of germs. During Washington's steamiest months, new eggs matured into adults in as few as ten days. Even in cooler climes, maggots matured quickly in poorly drained privies as they slurped down accessible liquid nutrients. In D.C.'s climate, an overwintering female laying her first clutch of eggs in mid-April had the potential to leave 5.5 trillion descendants by mid-September, though many young flies died off.20 In fall, most adults died off with the first frost, but some survived inside heated homes while juveniles went dormant in their pupal stage.21

Flight distances would determine flies' ability to connect diseased places with bodies elsewhere in the neighborhood or city. Howard asked, “Will the proper care of the stables and houses in a given city square relieve the houses in this square from the fly pest,” even if adjacent blocks remained filthy? He conceded that “the house fly will seldom travel very much farther than it has to fly for food and a proper nidus”—disease ecologists' term for nest—“but as a matter of fact it is very hard to prove this.” Experimenters who tracked flies found most within tens or hundreds of yards, but a few traveled for miles.22 The scale at which flies could spread germs thus remained uncertain; a roving fly might connect polluted neighborhoods with clean homes across the city.

New findings about the vector roles of flies and mosquitoes—along with rats and their fleas—arrived amid other changes in public health agencies' activities and also their relationships with citizens. For much of the nineteenth century, urban health departments emphasized general sanitation to clean up rotting organic matter that generated disease-causing forces called miasmas. These sanitation activities served as preventive medicine for all residents. The rise of bacteriology in the late nineteenth century enabled health agencies to target sources of infection, such as contaminated food or human carriers, with increased precision—a development some historians say reduced attention to general sanitation. Medical entomology raised new questions about the most efficient, effective ways for health departments to control disease. Some reformers—such as Leland Howard in 1900—believed that medical entomology justified both a focus on general sanitation to clean up environments that supported vectors and also the use of state power to protect citizens from disease. Others insisted that screens, poisons, and traps—often deployed in people's homes—could kill insects and rodents even if conditions outside favored them.23 These approaches expressed divergent visions of the role of the state, experts, citizens, and ecology in public health. Fly control would also occur in rather different urban spaces under these divergent visions. General sanitation promised to cleanse the entire fly-breeding landscape—manure-caked streets, alleys, and stables, along with any remaining privies. Meanwhile, approaches targeting flies themselves often focused on private homes and other spaces from which flies were to be excluded.

Medical entomology was one of many sciences that was applied and shaped by urban reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Progressives pursued a variety of agendas, often with competing practical and philosophical priorities. Reformers who embraced medical entomology called for government interventions at a variety of scales, exerting a variety of different powers. The tensions among various reform agendas helped shape approaches to public health in general, and fly control specifically. Some Progressives sought increased power for experts to manage cities and apply science in pursuit of orderly, modern landscapes—for example, the draining of wetlands to eliminate mosquitoes.24 Others sought to discipline citizens' conduct through education in sciences such as hygiene, home economics, natural history, and medical entomology—a top-down, paternalistic vision of relationships among the state, experts, and the people. Others, however, believed that government should first and foremost wield its power to protect and empower the least powerful citizens. These reformers, such as the activists at Chicago's Hull-House, used medical entomology to justify calls for democratic access, social justice, and environmental health for people living in fly-breeding landscapes.

SOCIAL JUSTICE, URBAN ECOLOGY, AND FLY-BREEDING LANDSCAPES

In the summer of 1902, typhoid fever killed some 450 Chicagoans, sickening many more. This was in spite of the new canal completed two years earlier—a feat that promised to ease the city's annual bouts with water-borne disease by diverting polluted river water away from Lake Michigan. The Board of Health responded to the outbreak with further measures to protect the entire city's water supply. Activists at Hull-House countered that the “peculiar localization of the epidemic” indicated a smaller-scale yet no less dangerous cause for many typhoid cases. Amid its engineering achievements, city government neglected landscapes where the most vulnerable Chicagoans lived. Hull-House stood amid one such landscape: the nineteenth ward. This district of working-class Greeks and Italians, along with Bohemians, Russian and Polish Jews, and Irish-Americans, suffered six times the city's average typhoid case rate.25 Hull-House activists argued that humble houseflies wreaked death upon the community as they flitted from broken-down privy to unscreened cottage.

On the blocks at the center of the outbreak, investigators Maud Gernon and Gertrude Howe, along with the physician Alice Hamilton, found abundant opportunities for flies to breed in human excrement. Nearly half of residents enjoyed working flush toilets as required by an 1896 municipal law, but their homes were scattered among properties that relied upon privies lacking sewer and water connections or whose cesspits were seldom cleaned. If maintained properly, liquid would exit through a pipe or trickle through an older cesspit's permeable walls; hired scavengers were supposed to remove solids frequently enough to prevent clogs. Waste in basins several feet deep should emit little fly-attracting odor as it composted. In Chicago in 1902, however, a landlord who violated the law by keeping a privy instead of a flush toilet might also delay hiring a scavenger until long after the cesspit clogged. Trapped liquids mixed with solids, brimming up close to the unscreened toilet hatch and enticing flies with their fragrance. Wet sludge nourished fast-maturing maggots, who emerged as adults close to the surface.26

The area's two thousand human residents exceeded the capacity of sewer lines laid decades earlier when housing and population remained sparse. Landlords packed three or more families into units designed for just one.27 “Only a moderate increase in rainfall” sent sewage spilling into yards and basements.28 To Hamilton, Gernon, and Howe, these conditions recalled military camps where surgeons had blamed flies for spreading typhoid four years earlier. They watched flies emerge from exposed cesspits and flit to nearby homes. Many typhoid patients lived in homes with working plumbing adjacent to tenements with illegal privies. The women thought that only “the agency of flies” in carrying typhoid germs could explain this case distribution.29

Hamilton, Gernon, and Howe captured flies and tested them for the typhoid bacillus to determine whether germs survived the flight from a privy to a neighbor's open window. At one site, family members emptied typhoid patients' bedpans into a privy full to within three feet of the opening. Stool had splashed and stuck to the side of the pit just shy of the ground, within easy access for flies. Flies on a fence across the yard bore typhoid bacilli on their feet. The women also found bacilli on flies outside homes that had five typhoid cases; these homes had working toilets that would have flushed infected stools away from any flies, however. Nearby, a tenement housed sixteen families but no apparent typhoid cases. The tenement's cesspit had filled to the brim when the landlord finally hired a scavenger in August, but the scavenger left the night soil in the alley for a week at the height of the summer heat. “Naturally, the place swarmed with flies,” observed Hamilton, Gernon, and Howe. They suspected that bacilli survived in the night soil from either a previous typhoid case in the tenement or a latent case there.30 Flies that touched infected stools could deliver typhoid to the neighbors with good plumbing.

The women deflected blame from residents because many had complained to city inspectors only to see their cases overlooked or dismissed. Each inspector covered such a large territory that many complaints received cursory attention, and the ordinance that banned privies contained no provisions to ensure their removal. Inspectors responding to complaints were satisfied if landlords simply had privies cleaned—a process that could increase exposure if the scavenger dumped the night soil in an alley. Furthermore, property owners with connections to the ward's political machine often saw their cases dismissed. Cases that made it to court sometimes resulted in fines less than the cost of cleaning up the hazard. Almost 250 privies remained scattered across the nineteenth ward, breeding flies; other wards throughout Chicago harbored no fewer than a thousand additional privies.31 Hull-House's report precipitated a scandal that swept several inspectors out of office.32 To Hull-House activists, municipal officials negated the city's sanitary achievements when they failed to protect poor communities from flies.

Investigators from Hull-House drew upon medical entomology to explain the ecological unity of urban society, homes, and the city at large. Hull-House centered its activism in homes and their surrounding neighborhoods as an expression of community support for domestic life and well-being. One Chicago activist called for municipal reforms to nurture “a city of homes, a place in which to rear children.” The professional, Anglo women who lived in Hull-House taught courses for poor women, men, and children, many of them immigrants; their work set up a paternalistic dynamic based on education, class, and ethnicity.33 It did so, however, in the context of activism that engaged community members, in hopes of creating a “sense of the economic unity” with “the large foreign colonies which so easily isolate themselves in large American cities.”34 For example, women in the community joined Hull-House residents to protest Chicago's privatized trash collection system, which left their district underserved—and a breeding ground for pests that thrived on garbage.35 Hull-House called for the city to not only exercise its engineering prowess but also wield its power to protect families from those who profited from neglect of neighborhood environments. By contrast, other reformers used medical entomology to distance city government from regular people by shifting power to scientific experts or teaching citizens to regulate their own conduct.36

MANAGING WASTES, HOUSING, PEOPLE, AND FLIES

Like activists at Hull-House, reformers in Washington, D.C., called for municipal authorities to protect poor residents by eliminating fly-breeding landscapes. Health officer George Kober first drew attention to fly infestation in his report on the 1895 typhoid outbreak. The report called for the city to extend sewer services, eliminate privies, and replace poorly constructed homes that flies could easily infiltrate.37

Leland Howard of the USDA Bureau of Entomology backed calls to eliminate privies and also recommended speeding the flow of manure, the most prolific fly-breeding medium, out of the city. Howard studied Washington's flies to discern their nidus. Flies visited kitchen garbage pails for food, but few laid eggs there.38 Instead, over 90 percent of flies in D.C. homes emerged from the horse manure that clogged city streets and stables. In late summer, as many as twelve hundred flies might grow up in a single pound of manure. Most other houseflies, though a small minority, had a more worrisome upbringing: they emerged from human excrement, where they could directly access intestinal pathogens.39 Howard called for local government to charge unscrupulous scavengers with a misdemeanor for dumping night soil in residential areas—a common crime in alleys where police protection was lax.40 For Howard, medical entomology informed efficient procedures for managing wastes and protecting public health.

Washington reformers' concerns about housing and flies centered upon African-Americans living in alley homes. Many established black families in D.C. made prosperous homes in black enclaves or a few racially integrated sites. Newcomers during and after the Civil War faced increasing racial discrimination, however, and in the days before further transit options became available, most housing remained concentrated in a limited land area close to the urban core. Developers packed tiny houses into back alleys on almost three hundred city blocks, from such fashionable spots as Dupont Circle to poorly drained areas in southeast D.C., exploiting high housing demand and the lack of options for black residents. As in Chicago's nineteenth ward, many D.C. alley homes remained unconnected to sewer lines; residents relied on privies, often in ill-repair. City authorities and the U.S. Congress—which oversaw the District—did little to intervene in the alley house boom, apart from condemning a few dwellings, until the 1890s. By then, some twenty thousand Washingtonians, most of them African-American, lived in alleys.41 Unlike Chicago's “foreign colonies,” which Hull-House described as isolated from the rest of the city, the alley-dwellers who were D.C. reformers' greatest anxiety lived on the same blocks as privileged residents. A labyrinth of fences and outbuildings obscured alleys from street-side neighbors, but flies easily spanned the distance between them.42

Concern for the poor motivated housing reform in Washington, but advocates lacked Hull-House's engagement with residents. Reports stigmatized alley denizens, asserting that alleys bred vice along with flies and disease. According to reformers' “breakdown hypothesis,” the move from rural areas to the city degraded family life; squalid, fly-infested domestic landscapes both marked and perpetuated this breakdown.43 Reformers hoped to uplift residents by destroying and replacing alley homes. A series of studies about Washington's alley homes began in 1895, led by George Kober as chair of the Committee on Housing the People, with help from the Women's Anthropological Society and the Associated Charities of Washington. Reports used flies as symbols of slovenliness encouraged by a disorderly environment. Surveyors portrayed residents breeding prolifically and wallowing in filth much like the flies that infested their communities. One noted: “To have swarms of children and let them die is characteristic of the alleys I have studied.” Another described a mother with tuberculosis languishing under a “low ceiling…almost black with flies, which the sick woman drove away from her face occasionally with a weak motion of her skinny arm.”44 Some medical investigators suspected that flies picked up tuberculosis when visiting infected sputum in spittoons or on floors.45 Images of flies evoked shame on both landlords and residents.

In 1902, President Roosevelt expressed shock over conditions “almost within the shadow of the Capitol Dome” and declared that all of Washington, not just its federal sections, must be made a model city. He called on Associated Charities president Frederick Weller to continue monitoring the alleys, while Congress supported demolition of more than five hundred alley houses and established two corporations to build affordable “sanitary housing.” Mortality rates in the new homes were lower than in the alleys, but only a few dozen units were available to the lowest-income residents or blacks.46

Meanwhile, Leland Howard made Washington, D.C., a laboratory for the study of flies; research by USDA entomologists informed urban sanitation policy there and across the United States. Howard blamed copious horse manure for breeding flies that became prolific germ-carriers. Like other cities, Washington struggled to manage its manure. Automobiles had begun to compete with horsepower, but horse stables for household or business use persisted in areas across the income spectrum.47 Many horse-keepers delayed manure disposal or kept manure in shoddy bins built over pervious ground and emptied at intervals longer than flies' breeding cycle. Even when haulers carted waste to farms in the hinterlands, manure spilled along the route could expose residents to flies.48

Based on the findings of his Bureau of Entomology, Howard prescribed new laws and processes for managing the manure that bred most of the city's houseflies. In 1905, summer typhoid deaths again alarmed the city, but the city health officer insisted that water pollution was the main cause. He stressed the need to improve filtration and disputed evidence that flies or privies were to blame.49 Still, in 1906, the District adopted Howard's proposals to tighten government control over stables and manure haulers. The city ordered haulers to carry manure along routes that minimized exposure in dense neighborhoods.50 Spilled or thinly spread waste helped juvenile flies evade control because maggots about to pupate instinctively migrate within their rearing media. If they reached the bottom of a pile of manure or human excrement, maggots might burrow into the substrate below, such as a dirt road or the soil of vacant lot, ready to escape upon removal of the waste.51 Because of this and flies' rapid reproduction in Washington's summer heat, the city also mandated twice-weekly manure clearance. Such frequent sweeps interrupted flies' life cycle before they could mature or lodge themselves in the earth. The new law dictated that stables be surfaced with impervious materials and equipped with fly-proof manure pits. Violators convicted of keeping fly-ridden stables would be fined forty dollars. The Health Department collected a list of all stables in the city so it could monitor and control conditions there. Laws were especially strict in the most densely populated parts of the city, to protect families at home from flies.52

From Hull-House to George Kober to Leland Howard, reformers who called for government to clean up fly-breeding landscapes saw homes as part of an urban ecology. They differed in their engagement with communities, but all believed that city government could protect citizens by eliminating privies, illegal night-soil dumps, uncontrolled manure, and poorly constructed homes. So long as the urban environment teemed with houseflies, families at home would not be safe. Transformation of backyards, alleys, and stables would require hefty public investment, however—similar in magnitude to grand feats of engineering but expended at a more human scale. Advocates sought citizen support for expensive reforms by emphasizing the ways flies connected people and places throughout the city.

“DEMOCRATIC” HOUSEFLIES AND VISIONS OF A CLEAN CITY

In an article for civil engineers about vector-borne disease, the entomologist W. Dwight Pierce advised his audience to think ecologically: “Little by little it has sunk into the human consciousness that your health and my health depend upon the health of every other living creature in our community.”53 The editor of the text Sanitary Entomology, Pierce exemplified the rhetorical use of insects' natural history to enlist political support for broad sanitary reforms. Flitting with powerful wings and attracted to odors from manure to milk, the housefly “visits everything under the sun,” explained entomologists who studied flies' role in the contamination of food.54 Pierce contended that flies could wander for miles, broadcasting even isolated cases of disease. “If we allow a disease to fester in part of the social body,” he warned, insects could deliver “poison thru the whole system.”55 Dr. Simon Flexner of the Rockefeller Foundation nominated flies as a possible vector for polio because they “possess the power to migrate over considerable territory” and “affect all classes of society.”56 According to this view of urban space, flies unified city-dwellers across social status and location. Middle- and upper-class citizens seldom saw or smelled fly-breeding landscapes. Still, reformers argued that by supporting fly control, the affluent would also protect themselves.

Washington's Associated Charities president, Frederick Weller, emphasized houseflies' tendency to cross social and spatial divides, unifying the body politic. “The democratic little house-fly carries disease germs from the disregarded plague spots and deposits them…upon the food alike of rich and poor, statesman and voteless citizen,” Weller cautioned.57 Associated Charities titled its 1908 study of alley-dwellers Neglected Neighbors, capturing reformers' frustration with Washington's privileged classes who gave little political backing for housing and sanitary reform. Government and charitable efforts failed to alleviate hazards that, Weller insisted, threatened the affluent along with alley-dwellers. Outmoded privies persisted in alleys, even after Congress passed a long-delayed act to eliminate such structures. Flies that visited these privies could sicken neighbors—rich and poor alike. Behind one alley home, for example:

the toilet box was found, on several occasions, badly soiled outside with excreta…. The fact that flies carry typhoid fever germs from such privies to the food supplies of neighboring houses should have made the residents of better streets around “Snow Court” take interest in the death from typhoid fever of a young girl whose infected excrement was deposited in this open box. Flies have especially free access to this privy, for it not only has no lids (few privy boxes do, although the law requires them), but it is not even enclosed in a toilet house…. This case of typhoid might readily supply germs to infect the resourceful residents on Pennsylvania avenue, less than two blocks distant.58

Flies easily spanned the distances between the privies of alley dwellings and the homes of more privileged and powerful Washingtonians.

Economic relationships also connected germ-bearing flies to affluent homes. Nannies, laundresses, and grocers who hailed from Washington's alleys served elite and middle-class families. Weller noted that statesmen's “nurse girls take the babies for occasional visits to alley homes,” feeding the infants bottled milk that both attracted flies and served as a prolific breeding medium for germs. Investigators from Hull-House also appealed to privileged Chicagoans by pointing to their connections with working people and horses that lived with houseflies in the nineteenth ward. “In this district are the stables of various large firms whose wagons are sent throughout the city and suburbs,” reformers wrote, “…the peddler's carts which carry fruit and vegetables in every direction within a day's journey start in large numbers from this region and their supplies are stored here. With all these go the house-flies bearing, as we may believe, the typhoid germ.”59 Flies thus reduced the distance between the homes of working-class immigrants and the kitchens and bodies of comfortable citizens, connecting disparate social groups in cities.60

The “democratic” label for houseflies carried double meanings: flies both bridged class divisions and also, some reformers hoped, hailed citizens to demand sanitary reform. The residents most plagued by flies held little power to alter municipal priorities, but perhaps broad political support could place sanitary stables, streets, and homes at the top of city agendas. Many reformers believed that medical entomology could inspire citizens to demand fly management, an issue long ignored by politicians. The “municipal housekeeping” movement among middle- and upper-class women exemplified this push to mold an articulate and compassionate citizenry dedicated to healthy homes. Municipal housekeepers sought to expand an ethic of care from their own homes to the living spaces of all city-dwellers by demanding public investment in sanitation.61 They interpreted medical entomology through this ethic and declared flies a public, political problem and not only one for housewives to deal with privately.

For example, Dr. Mary Waring, Health and Hygiene chair of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, framed environmental disease as a problem of racial injustice while also teaching blacks how to protect themselves against flies in the absence of government intervention. Many local chapters of the National Association promoted both hygiene education for households and political efforts to improve sanitation services in black communities. Waring disputed the common notion that “the Negro has a predisposition” to environmental diseases, describing a litany of sanitary inequities to which blacks were subjected. Waring demanded: “Is it not a fact that in many localities the authorities allow certain sections in which poor people live to remain in an unsanitary condition? Have you ever noticed the irregularity of the passing of the garbage wagon in some localities? Have you ever known landlords to refuse to furnish tenants with the living needs for proper disposal of excreta and sufficient water supply?” All of these unjust conditions bred flies in black neighborhoods, but authorities left blacks to control flies themselves while also suffering with disease, infestation, and stigma. Waring called “conservation of health and national vitality” as important as that of “the forest and coal”—a duty for the state, not citizens alone, but one that authorities neglected in poor, black communities.62

Marion Talbot, University of Chicago Dean of Women and home economist, noted in her guide Home Sanitation: “A small proportion of the effort now expended in encouraging people to kill flies, if devoted to training them to demand effective scavenging, would be much more likely to accomplish the end sought.”63 Talbot urged readers, mostly educated women, to exercise their privileged citizenship position to advocate for the community's basic health needs. Talbot believed most other means of household infection were the duty of individual women to address, so her endorsement of a public solution to fly infestation is particularly telling.

Leland Howard similarly believed that a citizenry educated in the dangers of flies would demand “increased appropriations for public-health work.”64 In 1908, Howard launched a campaign to replace the benign name “house fly” with “typhoid fly” in hopes of prodding citizens to lobby for improved sanitation. The proposal earned him censure from some entomologists and health officials for the possible implication that only flies carried typhoid; most believed that far more cases resulted from contaminated water or filthy human hands.65 The health director of Howard's home city of Washington doubted that flies caused many typhoid cases there, although he did support Howard's proposed stable regulations. Furthermore, in 1912, Charles V. Chapin, a respected public health leader, disputed Howard's charge that flies demanded municipal attention. Howard persisted, however, publicizing the fly's horrifying characteristics: its copious reproduction, its habit of vomiting digestive juices on food, its coat of tiny hairs that increased the surface area to which germs could cling, the “specks” that dotted walls, windows, and fixtures in infested homes. In 1908 he also had employees hang sticky flypaper at sites across Washington in hopes of proving an association between fly abundance and typhoid cases. The results were inconclusive, but a few sites yielded an impressive twenty-seven hundred flies in just two days.66 Howard strived to motivate householders to not only destroy flies themselves but also to pressure officials for citywide sanitation.

Municipal governments never seemed to invest enough in sanitation to achieve satisfactory fly control, though, even as dwindling numbers of horses left dwindling amounts of manure in streets and stables. Manure management, privy removal, and housing reform progressed, but many reformers worried that homes remained vulnerable to flies. Early measures picked the low-hanging fruit, so to speak, but continuing sanitary problems and fly infestations proved more stubborn. By the 1910s, health departments and reformers expressed disappointment that flies persisted in their cities. In some cases, reformers stepped up holistic measures, proposing stricter sanitation laws and taking on new clean-up activities. In other cases, they experimented with more focused measures, many of which targeted domestic space.

SANITATION STRUGGLES AND GROWING RELIANCE ON TARGETED FLY CONTROL

Leland Howard hoped to use the horrors of “typhoid flies” to push for bigger sanitation budgets, but he and colleagues at the USDA were forced to admit that “very often it is lack of funds which prevents public health officers from taking initiative in anti-fly crusades.”67 Washington's experience shows how municipal efforts fell short of eliminating fly-breeding landscapes and fulfilling sanitary ideals in general. Like many city health departments, Washington's seemed trapped in a pattern of responding to emergencies, such as typhoid outbreaks, rather than budgeting in advance for comprehensive environmental and housing reform.68 Howard complained of poor enforcement of the city's “excellent” stable ordinances, “the chief reason being the lack of a sufficient force of inspectors.”69 Also, “sanitary housing” built to replace alley dwellings represented but a “drop in the bucket” of all the District's substandard homes. Condemnation of alley homes had “intensified the housing problem” because landlords raised rents on the diminished supply of units. Residents invited more family members and boarders to share rents for their tiny dwellings, straining the capacity of toilets still unconnected to sewers.70 Flies continued to thrive in Washington's privies and manure piles even as reformers strived to modernize the urban environment.

Washington, D.C., struggled not only to deploy inspectors to stables but also to dispose of manure, in part because of the city's expanding population and suburban footprint. U.S. cities had long exported organic wastes—horse and human manure alike—to farms on their outskirts to serve as fertilizer.71 A year after the new regulations, Washington health officials lamented that “with the growth of the city, the volume of manure to be disposed of has increased, and the distances to which it must be hauled in order properly to dispose of it have lengthened.” The connections between Washington's stables and their historic manure sinks (rural farms) were stretched to their limits, and many farmers declined to pay rising transport costs.72 Health authorities called for a tax on horses to fund public manure collection services, but their proposal failed.73

Health inspectors soon stepped up enforcement of stable regulations, quadrupling inspections and entering some two thousand stables in the new city registry.74 Horse owners searched for places to dispose of dung, and some of those who struggled to comply with city stable ordinances were alley-dwellers themselves. Many hewed to their rural origins by keeping an array of livestock in their new urban homes; affluent, established neighbors facing the street also kept horses, but had more resources to support them. Whether flies emerged from street-side or alley-side manure, however, they need travel but a few yards to find an open privy, potentially teeming with germs. Canvassers noted that the manure of a horse kept in “Snow Alley” bred clouds of flies that issued into an open shed where typhoid stools had been dumped.75 Actions against horse-keeping in alleys recalled the crackdown on Italian and Chinese immigrants' chicken-raising practices, which, authorities charged, supported rats during San Francisco's 1907–8 plague outbreak.76 In Washington, as in San Francisco, some regulations aimed at preventing infestation fell the hardest upon migrants—whether from abroad or the rural South—who brought their agricultural traditions with them to the city.

Leland Howard and other reformers strived to preserve ecological connections between cities and farms while also protecting city-dwellers from the flies reared in horse manure. Howard recommended applying pesticides to manure as the prospects for good manure management grew dimmer. One poison, borax, killed larvae when sprinkled over infested dung but seemed also to harm plants grown on the manure. Another, the plant-based hellebore, could actually improve crops but might be poisonous to livestock as well as fly larvae.77 In his career, Howard grew disillusioned with other ecological control methods when efforts to deploy predatory insects against agricultural pests met with their own logistical failures.78 Other entomologists recommended poisoning manure to prevent fly-borne disease; Illinois state entomologist John J. Davis boasted that iron sulfate would kill Chicago's flies and eliminate typhoid cheaply, and without damaging the value of manure.79 These scientists began to resign themselves to pesticide-based methods of fly control in the face of continuing health threats from flies, while hoping to maintain the value of urban horse manure.

Cities' perpetual struggle to metabolize human and horse excrement led one reformer to declare the futility of efforts to eliminate fly-breeding landscapes: “In the city, the miles of gutters and sewers specially constructed to carry off filth, the public dumps and stray accumulations…and in the country the miles of roadsides and acres of barnyards and pastures, and the train-loads of manure from the cities, render attack upon the breeding-places of the fly utterly hopeless and impossible.”80 According to the biology professor and textbook author Clifton Hodge, organic wastes and the flies they bred would always evade state control and thereby endanger families, despite efforts to modernize urban infrastructure. Thus, Hodge called for citizen education in the sciences to inform and motivate home-based antifly campaigns.

Like other reformers, Hodge championed fly control as a means of citizen engagement with urban environment and community. Compared with Alice Hamilton or Leland Howard, however, Hodge saw the locus of pest control as much more decentralized. Asserting that municipal governments could never eliminate all fly-breeding, Hodge hoped to instruct citizens in scientific and hygienic principles so that they would alter their own conduct and take greater responsibility for fly control themselves. Individual environmental managers—women, children, and families—would learn about medical entomology from popular journals, public lectures, and school courses using Hodge's textbooks. Fly-control activities took place in the home but, Hodge argued, could eliminate flies across entire communities. Dr. Arthur Corwin's poem “Clean Up” conveyed a similar sentiment about the relationship between domestic sanitation, pest control, and civic spaces: “the city is your home.” So did the American Civic Association (ACA), which promoted fly control as part of hygiene and city-beautification campaigns.81 Hodge, Corwin, and the ACA insisted that homes were connected to urban society and nature but believed that environmental improvement must come from labor in the home, rather than reforms targeting the public sphere.

Hodge boasted that citizens of towns and small cities in Wisconsin, California, and Oregon had abolished flies through households' near-universal participation in early season trapping. He promoted a simple fly trap of his own invention that featured a screen dome a few inches in diameter to be affixed to a garbage can lid. An early model of the trap “merely set upon a pile of filth” caught over nine gallons of flies in a single week.82 Hodge envisioned an urban landscape where fly traps stood vigil by every front porch and back door in early spring to catch flies emerging from hibernation before they could breed. Indoors, smaller traps and child-safe insecticides destroyed any flies that slipped past the borders.83 Hodge supported municipal sanitation, but he remained pessimistic that environmental cleanups would ever protect families from fly-borne disease. Instead, citizens had to learn how to make their own homes safe, and with them, the entire urban environment.

Hodge aimed to mold children into citizens aware of their own ecological and social implications. He called for schools to instill in people from cities and suburbs alike an ethical and scientific concern for their environment.84 For Hodge, this included not only beloved or useful organisms—flowers, pets, or wild fauna; crops, livestock, or honeybees—but also pests and microbes that did harm. For him, the civic space of the biology classroom could forge links to homes by helping young citizens to learn to protect their own bodies—and those of their families and communities—from household pests.85 Hodge emphasized in his basic text, Nature Study and Life, that “one of the chief aims of this book is to unite home and school.”86 In other words, if school is a crucible of citizenship for young urbanites, then lessons must cultivate a sense of duty to the environment by teaching children to steward the ecology of their own homes.

Hodge's works for students as well as for adults stressed that responsibility for flies transcended public and private spheres. A good biological citizen would do her or his part in private space to help make the entire city clean, healthy, and free from pests. Hodge offered lesson plans that engaged children in making fly traps, observing maggots in glass jars, and tallying possible cases of fly-borne disease in their neighborhoods.87 Hodge acknowledged that children might not want to discuss in class which insects infested their own homes, especially when bedbug problems might lead to ostracism; teachers must broach such topics with a “superhuman amount of tact” while making sure that the school did not become a point of dissemination for vermin.88 Whatever creatures infested children's homes, Hodge believed that understanding the connections those pests made between nature, home, community, and health would produce responsible and healthy urban citizens.

Hodge's secondary-level text Civic Biology, like other school books with similar titles, aimed to provide older students with the scientific and moral foundations of urban and environmental citizenship. “Civic biology” advocates called for science courses in urban schools to teach young urban citizens to solve problems through cooperation and biological literacy. Students should learn to focus watchful attention on their homes, their bodies, and the bodies of their eventual children, particularly on the connections between bodies and the collective environment. For Hodge, houseflies exemplified those interconnections because “one careless or ignorant household can breed flies enough to infest all the houses within a quarter mile.”89

Other educators aimed to make pest control a source of pride for school-children. Some cities paid children bounties for catching flies, although Hodge warned that such incentives should be limited to early in the breeding season, when killing adults would have the greatest impact. In Chicago, a young girl proudly sent a fly she had swatted dead to the Board of Health, which ran a photo of the mangled corpse in its hygiene newsletter. School groups staged the play “Swat the Fly” in which domestic pets rally around a boy in his struggle to kill a diseased insect.90 These activities aimed to instill in children a sense of their own effectiveness and duty in managing domestic environments.

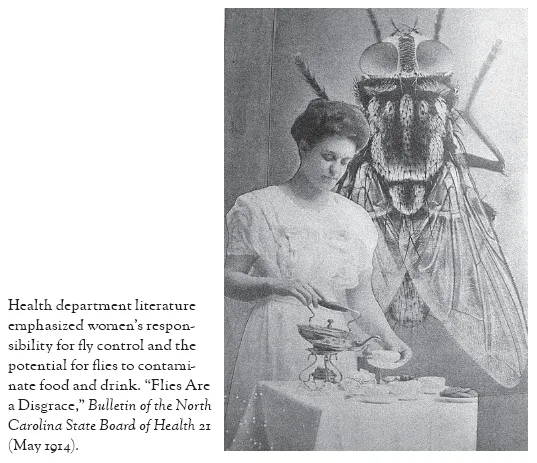

Hygiene educators sent a stronger message to adults, especially housewives, to equip their homes with the means to exclude and kill insect invaders rather than rely on citywide sanitation. Messages to women and families ranged from disciplinary to scientific to outright fear-mongering. Some insisted that women must attend to fly control with constant vigilance. Chicago's Board of Health advised that even in winter “every housewife should…go carefully over her house to see that there is not a fly now living in it.”91 Hodge explained that such vigilance was necessary because in colder climes, flies “hibernate as young adults in cracks about buildings. They come out of winter quarters ravenously hungry and feed for about a week…before beginning to lay.”92 Meanwhile, a North Carolina state health bulletin demanded: “Are you a careless housekeeper? Be sure the flies will find you out…. Flies are a householder's own fault. If you want to keep your own-self-respect and that of your friends and neighbors, don't let anyone find your house full of flies.” The bulletin blamed one thousand to two thousand infant deaths on flies in that state alone.93 As flies persisted despite sanitation efforts, hygiene educators called for citizens to manage flies at the bounds of their own homes.

Families could purchase a variety of implements to protect their homes against flies. Marketers seized upon suspicions about fly-borne disease to promote window screens in northern parts of the United States; yellow fever outbreaks and endemic malaria had already prompted public screening drives in the South.94 Companies offered traps, swatters, flypapers like the brand Tanglefoot, as well as a variety of fly poisons. Many devices and chemicals had already been available for households who saw flies as nuisances; as suspicion of flies spread, companies could tout their products as lifesavers, with the endorsement of health authorities. Companies sent the implicit message that health was a consumer product women could choose for their families when they promoted gadgets, concoctions, and services to protect against germs in the home.95 This contrasted with the message from other reformers that sanitation was a public good to be shared among all city-dwellers.

Bureau of Entomology chief Leland Howard lamented that the nation spent ten million dollars per year on window and door screens against flies when preventive measures would maintain cities in a healthier, more sanitary condition. “The whole expense of screening should be an unnecessary one,” he argued, “just as the effort to destroy flies in houses should be unnecessary. The breeding should be stopped to such an extent that all these things should be useless.”96 Howard called for municipalities to remove the root causes of fly infestation by modernizing sanitation systems instead of leaving families to rely upon screens, traps, or swatters. Howard's home city of Washington, D.C., however, rallied some twenty-five thousand households to “swat the fly” during a 1912 campaign.97 Window screens, swatters, and household poisons reinforced the notion that private homes could be separated from the polluted city outdoors, contradicting notions of interconnection. By the 1910s, many reformers saw window screens as the answer to persistent houseflies.

Chicago's Board of Health conveyed mixed messages about screens. In a 1916 cartoon in its health education newsletter, a man installs a screen window while enormous flies swarm from his own curbside garbage can, carrying the demonic figure of disease. The caption read, “Our greatest enemy is not foreign, but domestic,” punning on debates over the United States's entry into the Great War in Europe while also locating the source of the fly problem within the bounds of one resident's premises. Other Board of Health publications promoted screening, but this one seemed to suggest that citizens could better prevent fly-borne disease through better stewardship of their own garbage.98 The cartoon portrayed a man doing the screening, but health departments aimed much fly-control education at women, making maintenance of screens and other household fly-control tasks part of mothers' duties to protect their infants and children. Flies became entangled with new ideas about scientific motherhood as well as anxieties about children's health and the cleanliness of the milk they were fed.

MOTHERS, CONTAMINATED MILK, AND FLY SCREENS

Reformers' responses to another public health trend paved the way for increasing focus on domestic-scale fly control by mothers. For much of American history, mothers' custom of breastfeeding babies through at least their second summer had protected infants from food- and water-borne illness. In U.S. cities at the turn of the twentieth century, mothers increasingly weaned their children onto cow milk and solids by three months of age. Babies this young could not yet fight off gastrointestinal germs for which cow milk provided a rich growth medium. As late as 1916, over thirty-four hundred Chicago infants died of diarrhea, 6 percent of babies born that year. At least 37 percent of all infant deaths were due to diarrheal disease.99 Those who survived a bout of diarrhea suffered dehydration, poor growth, and susceptibility to other diseases. The shift toward early weaning brought flies into the ecology of infant feeding. Experts warned that cow milk—unlike milk suckled directly from mothers' breasts—suffered myriad microbial insults in its journey from udder to hungry belly, including those delivered by flies.100

Homes were not the only spaces where health advocates intervened to protect infants' food from flies; farms, milk trucks, grocers, and restaurants also became targets for regulation. The “scientific motherhood” movement had opened domestic space to scrutiny by the state and experts, making homes an important intervention site.101 Household fly control became one element of domestic science taught in classrooms and by in-home educators. Visiting nurses promoted safe infant feeding when they checked new mothers' homes for flies along with other violations of cleanliness.102 Educators implored mothers to prevent flies from touching milk and food. The association of fly infestation, infant mortality, and changing infant feeding practices made fly control a moral issue for educators and public health officials. For these advocates, mothers who fed their infants improperly had already failed in their maternal duties, and flies in a home marked women as poor mothers. For health educators, nurses, and social workers, the sight of flies crawling on babies' faces, milk bottles, and porridge bowls in districts with high infant mortality rates seemed to confirm maternal failure. Canvassers for Washington's Associated Charities considered it an indicator of alley-dwellers' moral degradation when they saw “nursing bottles…lying on the floor or anywhere else, partly filled with souring milk and black with appreciative flies.”103 Associated Charities urged housing reform as a solution to such health hazards, but other reformers targeted mothers directly with fly-control education and surveillance.

In light of flies' persistence and continued deaths from infantile diarrhea in some sections, New York City's Health Department in the early 1910s considered adding a screening requirement to its health code.104 New York hoped to intervene in poor families' homes to sever their connection with outdoor landscapes still marked by inadequate sanitation. In 1913, the Department of Health commissioned a study by the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor to test the effectiveness of a variety of fly-control strategies, including screening, education, and sanitation, for reducing infantile diarrhea. Since its founding in 1843, the association had strived to aid poor families it deemed “worthy” by correcting conditions it believed contributed to residents' ill-health and moral failings. Its activities ranged from building and running model tenements, to teaching immigrant mothers about modern American child-rearing, to sending urban children to visit “fresh air” sites outside the city.105 With the study of fly control and diarrhea, the association hoped to show correlations among outdoor and indoor environments, mothers' conduct, and babies' health. Screens would serve as a technology for sealing off the home from disease and also as a means for reformers to extend state power over citizens' hygiene in private space.106

In neighborhoods targeted for the study, both domestic spaces and outdoor and commercial landscapes favored flies. The association chose for the experiment an Italian tenement district in the Bronx that “boast[ed] all the equipment necessary for the lively perpetuation and joyful existence of the house fly.” Poor conditions both indoors and out gave flies “a short circuit…between filth and food.”107 Nearby stables housed dozens of horses whose manure—and sometimes corpses—might remain long enough to nurture a generation of young flies. Four-story brick tenements on “congested” blocks were poorly served by both trash collection and sewers. Enclosed backyards functioned as illegal but convenient garbage dumps; many contained toilet sheds. Clotheslines ran between the open, unscreened windows of adjacent tenements.

In the first of two experimental years, investigators launched intensive fly-control efforts both indoors and out. The experimental design did not attempt to isolate the effects of outdoor sanitation from the effects of screening or education; the experimental blocks received all treatments, while control blocks received none of them. Visiting nurses taught some three hundred mothers on the experimental blocks about the dangers of domestic flies. Boy Scouts sealed seventeen hundred doors and windows with screens. Meanwhile, authorities performed intensive sanitation of stables, streets, alleys, and outdoor toilets.108 Mothers' responses to the experiment left investigators unable to evaluate the effect of screening homes against flies, however. Most mothers found that screens stifled everyday interactions between domestic and public space. They removed the screens soon after installation so they could lean out of windows to communicate with family and neighbors outdoors. Investigators found that “during the warm weather”—the very moment when flies and disease pathogens reproduced most quickly—“it was practically impossible to keep the screens either in or closed. Not only were they taken out, but they were torn out, and in some cases destroyed.”109

On the other hand, the association found that a combination of intensive outdoor sanitation and education protected children's health without the help of window screens. Even without window screens, fewer than half as many infants and young children contracted diarrhea on blocks cleansed of sewage, garbage, corpses, and manure than on adjacent, poorly served blocks. The association's 1913 study was one of the first to show the effectiveness of sanitation against fly-borne disease in a Northern city, albeit with a small sample size.110 The experiment provided no evidence for the value of screens; it revealed only women's resistance to them. Still, the association and the Board of Health wished to sharpen their focus on household-scale interventions against flies. The association insisted that future studies must “be carried on in the home itself” and that “complicating outside general sanitary influences should be avoided” so researchers could “arrive at an accurate value” for home-based fly control.111 A new experimental design tested whether homes could be isolated from filthy outdoor spaces.

The following year, mothers on the Lower East Side, most of them immigrants from eastern Europe, resisted the association's second screening experiment: “For the women of the lower East Side, a window possesses an importance of the first magnitude, and the suggestion of screening a window in such a way as to curtail ever so slightly its important social function will not readily be entertained. Even sliding screens, the installation of which amounts to a very considerable sum, were found to be quite impracticable.”112 The association imagined that unscreened windows exposed homes to the diseased public realm and that education about medical entomology would persuade women to exclude flies. For mothers, screenless windows and doors served as fluid conduits between domestic space and the public street, a function that reformers with the association and the Health Department failed to anticipate.

The Department of Health and the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor continued to urge mothers to cooperate with household fly control. After women on the Lower East Side tore out window screens, nurses introduced nets for covering cribs and prams. After its second year of trials, the association claimed that if mothers were negligent housekeepers, practiced “artificial feeding”—as opposed to breastfeeding—and also refused both screens and netting, they placed their babies at risk for illness and possibly death.113 The association and the Health Department sought greater control over domestic space to protect babies and their food from flies, even while evidence suggested that providing sanitation to underserved neighborhoods without screening improved babies' health.

One architectural historian has described screens as a “humane” innovation that allowed families to enjoy porches and cooling night breezes without annoyance or disease risk from mosquitoes and flies.114 Women's resistance to New York City's screening experiments belies assumptions about the universal embrace of such domestic technologies. From the state's perspective, attempts to contain flies dovetailed with efforts to contain citizens. Screening, however, seemed to accomplish neither.

DWINDLING FLIES IN CITIES OF MODERN TRANSPORTATION

As the air warmed in mid-April 1920, in southeast Washington, D.C., a housefly broke free from the pupa in which she had spent the winter. She climbed toward the light that peeked through the loose slats of a two-hole privy soon due for a cleaning. The fly emerged into a world quite different from the one that had nurtured so many of her species on the same block just twenty years earlier.

She had spent her whole life in one of the poorest parts of the city, an area still neglected by city environmental services. But even the most neglected blocks in Washington had begun to change. Car garages now outnumbered horse stables. The remaining two stables had new, paved manure bins. Manure disposal still proceeded slowly, but with fewer horses there was less manure overall—and therefore fewer places to rear maggots into full-grown flies. The privy from which the fly had emerged was one of just a few remaining on the block. As the fly searched for her first meal as an adult, she found fewer scents in the air than her forebears had twenty years ago. She finally flitted to a privy in which a family dumped its kitchen garbage. There she sucked bits of rotting meat from moldering bones.

The fly flew toward a small house that gave off cooking odors. Several flies were already crawling on a door screen, unable to enter the kitchen. The fly rested on the screen until she detected a strong movement of air around her. Sensing potential danger, she beat her wings and then alit upon the house's outer wall. As she crawled toward the odor again, she found her way indoors through a gap between the door and its frame.

Early twentieth-century cities provided ideal ecological conditions for houseflies to thrive. Many commentators insisted that flies in any part of the city endangered all districts because of flies' ability to migrate across neighborhoods. Most accounts suggest that houseflies spent much of their lives in poor, immigrant, and black communities, however. It was also these groups who lived with the wastes that attracted and supported flies: horse manure left in place too long, privies by the hundreds or thousands that landlords failed to replace, illegal human waste dumps, and garbage poorly managed by either households or by public or private service agencies. The landscape of urban fly-breeding reflected these environmental and political inequalities.

Some of the early reformers who embraced medical entomology made infestation a political issue. Leland Howard called for citizens to demand a reordering of municipal priorities to put sanitation and its enforcement at the top of the agenda. Mary Waring and Colored Women's Club chapters addressed both the public and private sides of flies, condemning racial inequities in sanitation services while promoting household-scale fly control to communities for their own protection. Hull-House approached fly control holistically: it denounced code enforcers for leaving fly-breeding hazards in the nineteenth ward, while at the same time organizing protests and teaching hygiene there. Alice Hamilton, one of the leaders of Hull-House's study on typhoid, later retracted the fly-based explanation of Chicago's 1902 outbreak when the city Board of Health admitted to covering up a sewage leak that more likely caused the high case rate near Hull-House.115 Even this revelation reinforced a larger point about infested communities. Immigrants, the poor, and blacks often lived with the city's worst filth, and authorities did too little to protect them from poor sanitation, regardless of flies' role.

Housing quality was also a factor in communities' exposure to flies and disease, and housing reformers in Washington, D.C., strived to make sanitary homes a political priority. Their attitudes toward flies, privies, horse-keeping, and other environmental conditions distanced them from communities rather than engaging them. Certainly, infested communities were in part responsible for the flies in their midst, particularly in the way they managed horse manure. Residents' sanitary failures were themselves abetted by public failures in code enforcement and waste collection and in the state's tolerance of racial segregation. Associated Charities portrayed flies as indicators of moral decline, justifying outside control over poor blacks' private spaces while failing to engage them in political efforts to improve conditions. Demolition of alley homes left residents more vulnerable to disease and their living situations more unstable, while offering them little help in controlling their own environment.

Halting fly reproduction through sanitation, health inspection, code enforcement, and housing reform proved a daunting, expensive task. Municipal governments balked at the cost of collectors, inspectors, and sanitary homes, leaving the job half-done. Flies persisted as sanitation and housing remained underfunded, leading reformers such as Clifton Hodge to urge devolution of fly-control activities to households. This shift in emphasis represented a distinct vision of urban ecology—more atomized and fragmented to the scale of the family, blind to structural inequalities. Visions of modern homes well kept by modern housewives eclipsed visions of efficient and equitable sanitation and code enforcement. Citizens whose homes still harbored flies became all the more backward in the eyes of reformers. For instance, in its own quest to show that control of the domestic scale was important for controlling flies and disease and to make mothers responsible for fly control, the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor seemed uninterested that the results of its first study supported intensive sanitation. Meanwhile, another research team captured the difficulty of controlling flies once they already existed: “It is almost impossible to keep [flies] out of our kitchens, dining rooms, cow stables, and milk rooms.”116 Reformers who called on women and families to seal off their homes against swarming flies asked them to do the impossible given widespread pollution in neighborhood environments.

Modernization of citizens, homes, and sanitation were not ultimately the key to fly control; rather, it was modernization of urban transportation. Cars in garages replaced horses in stables; Washington's stables began to close by the hundreds in 1917.117 Both Leland Howard in Washington and social workers at Chicago's Hull-House noted declining horses and flies coincident with the rise of automobiles and improved health.118 The decline of urban horses brought more significant environmental changes than did public investment in sanitation, housing, or citizen education, severing ecological ties with one of the two urban species upon which flies relied the most. Public investment in the urban environment was seldom sufficient to bring about such dramatic changes in pest populations. Many other pests could still rely for their survival on the human species along with its homes, cities, and social inequalities.

![]()

2

BEDBUGS

Creatures of Community in Modernizing Cities

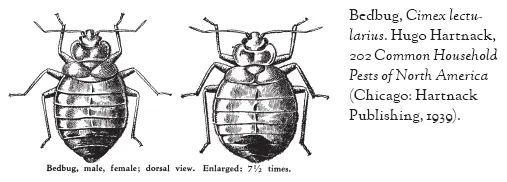

Hundreds of Cimex lectularius rested throughout a long summer day in 1920 in a flat on Chicago's West Side. Most huddled together on the narrow wooden bed frame on the lodger's side of the flat's single bedroom. Some hid in grooves in a chest below the foot of the bed, others under peeling wallpaper or behind a framed picture, leaving a blotchy crust of feces and egg cases. A few squeezed between loose floorboards.

As night fell, the lodger returned to his quarters, which smelled faintly of overripe raspberries. In the wee hours, the bugs finished digesting their previous meal. Roused by hunger, they sensed the lodger's breath and body heat and crept toward him.1 The bugs crawled onto the lodger's limbs and trunk. Each one pierced his skin with two barbed mandibles, then inserted its other mouthparts, two tiny tubes. One tube delivered saliva that carried an anticlotting agent, and the other sucked up the host's blood—a process that might take five minutes for a nymph or ten minutes for an adult. The saliva provoked an allergic reaction, and itchy weals soon rose on the lodger's skin.2 He stirred frequently, scratching bites old and new and smashing several bugs. As the bugs' engorged abdomens burst, the blood left red-brown spots on the sheet. Most escaped the lodger's thrashing, crawling off his body and back to their abodes.

The woman of the house and her daughters shared a bed on the other side of a partition. Two Sundays each month, dozens of bugs perished as the two girls spent the afternoon scrubbing kerosene into the bed frame and banging their mattress with a broom handle over a tub of used bathwater.3 Thanks to this routine, their side of the partition had fewer bugs than the lodger's, but they never rid themselves of every one. Tough cases protected eggs from kerosene, and mother bugs' gluey secretions kept them stuck to the mattress.4 Some impregnated adult females dispersed away from the main colony on the bed frame. These females laid a few eggs each day in hidden spots—cracks in the floor, between books on a shelf—while escaping both human control efforts and male bugs who attempted to reinseminate them by rupturing their abdomens.5

The nymphs emerged a week later, nearly colorless, and smaller than a millet seed, hungry for their first meal; incubation took longer in winter. Those bugs that evaded control turned a deep red hue from the blood they ingested. As their abdomens filled, adults bulged to the size of a sunflower seed meat. Between meals, their abdomens appeared to deflate; this, along with their color, earned them the nickname “mahogany flats.”6

Bugs from the lodger's side of the partition replenished the population on the other side, migrating slowly on their own six legs or more rapidly as hitchhikers on the lodger's clothes that happened to drop off as he walked by. Bugs also rained upon the clothesline when the upstairs neighbor shook out her rugs. The lodger's mattress, bought from a neighbor, had been the original source of the infestation. Once, a bug rode the younger girl's coat home from school. Some bugs even traveled across town, joining the elder daughter in the handbag she carried to her housekeeping job. Her employer had recently hired an exterminator to eliminate bedbugs from the home.7