![]()

1

PROBLEMS AND PRECONCEPTIONS

Each time one sees it, your body gives new joy

For its sight cannot ever satiate, its aspect is so pleasing.

Where else would these virtues of a Tathāgata [Buddha] be well housed?

Except in this form of yours, blazing with signs and marks.

Mātṛceṭa’s hymn to the Buddha in the Śatapañcāśatkastotra

[The Buddha said:] “What do you think, Kāśyapa, is any . . . human or non-human even able to make an image of the Tathāgatas [Buddhas]?” Kāśyapa said: “No, Blessed One. Since a Tathāgata is unexpressible, his body inconceivable, because of that it is not easy to make an image of them.”

Kāśyapa and the Buddha discussing images in the Maitreyasiṃhanāda Sūtra

IN the decades following the start of the first century CE, Buddhists in South Asia had a great deal to say on the subject of images and their use in religious contexts. Yet for all this information, it is futile, or at least misleading, to ask for a singular response to the question of what they thought about visual representations of the Buddha. Although it can be difficult to accurately date textual sources, it is safe to say that views on image use varied widely, and the views of individual authors only occasionally conformed to those expressed by other Buddhists.

The Divyāvadāna, for example, includes tales of monks achieving advanced spiritual states merely by seeing a copy of the Buddha’s bodily form.1 In contrast, the Maitreyasiṃhanāda Sūtra warns that image use is a risky distraction best left to the misguided, because Buddhas naturally defy any form of embodiment.2 Buddhaghoṣa espoused a slightly more moderate view; in his commentary on the Pāli Vinaya he concedes that meditation on the Buddha’s image may be acceptable for beginners, but he argues that it has no role in attaining higher levels of insight.3 Not only does the Avadānaśataka assert the exact opposite to be true, it identifies meditation on the form of the Buddha as a necessary prerequisite for the attainment of Enlightenment.4 Similarly high regard for the Buddha’s image inspired Mātṛceṭa to write hymns of praise extolling the virtues of the Buddha’s form and the benefits of envisioning it.5 In jarring opposition, one version of the Aṅguttara Nikāya denies even the possibility of successfully representing the Buddha’s form in any way.6

It would seem that under the placid surface of the waters we collectively refer to as “Buddhism” there were deep currents pulling in very different directions. Although we can now look back on these texts and deduce that they represent a range of views shaped by sectarian affiliation, regional factors, historical shifts, and individual beliefs, the texts rarely identify themselves in such fashion and frequently claim to speak with the authority of the Buddha himself.

If we need to be cautious in making general claims about Buddhist ideas on image use, we also need to be wary of treating the Buddhist acceptance of figural art as something that happened at a singular moment or for a singular reason. What emerge from the sources, both textual and material, are a rich variety and wide range of views that never actually coalesce into a single, pervasive point of view. This book constitutes a portrait of an uneasy relationship between the Buddhist authors and depictions of their Teacher, whose form is sometimes rejected entirely, frequently tolerated, and rarely embraced unconditionally. Most typically, Buddhist sources produced during and after the first century adopt a middle ground between outright rejection of and total comfort with image use. These sources are replete with explanations, justifications, and restrictions seeking to regulate the viewer’s relationship to the art.

Given the piecemeal nature of the historical evidence, a comprehensive catalogue of the full spectrum of South Asian Buddhist views on images use is not possible. What is possible is a study of the major concepts, concerns, and issues that recur in the textual sources or can be traced in the archaeological remains. This book is an attempt to understand the history of Buddhism’s relationships with figural art as an ongoing set of negotiations within the Buddhist community and in society at large. Any hope of understanding early Buddhists’ views on figural art requires that we situate these individuals within the world they inhabited and examine the cultural practices and concepts they would have considered familiar.

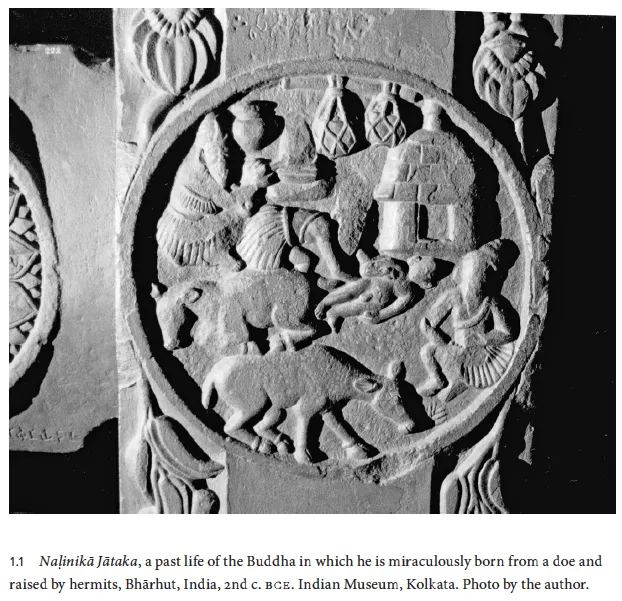

It is fascinating that in the mid- to late first century, roughly five hundred years after the Buddha lived, South Asia saw a tremendous burst in image production. A major increase in the figural art associated not only with Buddhism but also with Jainism and early forms of important Brahmanical gods, such as Kṛṣṇa (Krishna) and Sūrya, is evident in the material record of regions across parts of South Asia. Certainly there was figural art in South Asia before that time. Nevertheless, previous figural art appears to have been used almost exclusively for narrative scenes and for the depictions of a variety of popular deities (or spirit-deities).7 For example, decorations at the second-century BCE Buddhist site of Bhārhut include scenes from the Buddha’s past lives and prominent depictions of regional deities, all clearly identified in inscriptions left by the sculptors (figs. 1.1 and 1.2). The narrative art from this early period includes images of fictional characters, historical figures, or scenes from important tales. The religious images depict all manner of demigod, spirit-deity, deified ancestor, and restless dead. Numbered among these representations are some of the earliest large-scale, freestanding figural sculptures produced on the subcontinent (fig. 1.3). However, to my knowledge there is no extant, verifiable depiction of a living person made in South Asia before the first century.8 And even if one were to be identified, it would be a rare exception in the midst of a rich material record that overwhelmingly shunned such subject matter.

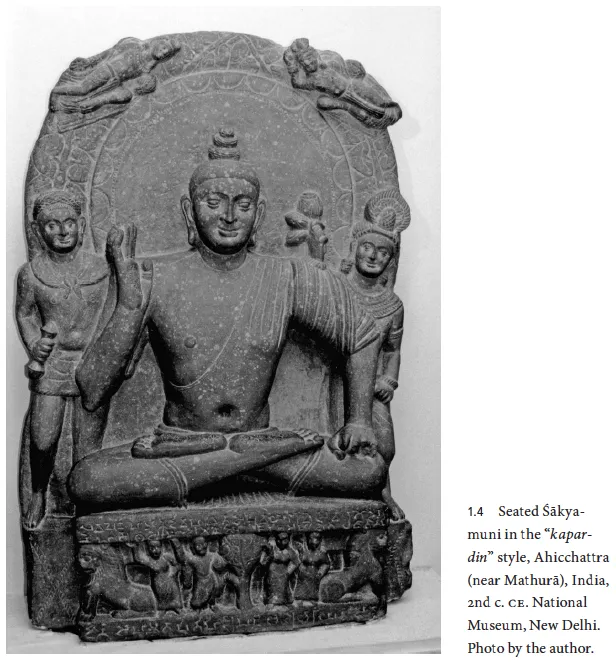

After the first century CE a cultural shift occurred in which a whole new range of topics became viable as subjects for depiction. The appearance of royal portraits is perhaps the clearest expression, but this new repertoire also included categories of beings that occupied more complicated positions between the living and the dead. Broader categories of Brahmanical gods (devas), Jain Tīrthaṅkaras, bodhisattvas, and the Buddha himself emerged as major subjects despite these traditions having had long histories with little or no custom of figural representation. Images such as the well-known seated portrayal of Śākyamuni from Ahicchatra exemplify the first tentative steps in this newly emergent figural tradition (fig. 1.4). This development is particularly significant because in previous centuries, some of these same subjects, notably any image of Śākyamuni (the Buddha), appear to have been studiously avoided.9 The profound changes identified in the material record are only one part of a larger cultural process that was contingent on political, cultural, regional, and transregional factors.

Given this, it is perhaps not surprising that a corresponding burst of interest in portraits and likenesses can be seen in the texts of this same era. What is perhaps more surprising is the intense fascination, almost fixation, and sheer frequency with which literary sources address the topic. There is also a commensurate critique of image use that became articulated in these same centuries as the more tradition-minded authors had, for the first time, to defend their viewpoints in response to new ideas. Yet the treatment of images was not confined to the pages of doctrinal polemics; images appear in other literary contexts as well. Narrative tales employed portraiture as a plot device or poetic trope, art manuals advised artists on proper forms of practice, legal codes commented on the regulation of images, and all manner of philosophic and religious texts grappled with related metaphysical questions.

For Buddhists, this obsession was fixed squarely on the image of the Buddha himself, and if this study were restricted solely to Buddhist sources, it might well appear that the emergence of the Buddha image was a unique innovation. It is important to remember, however, that the emergence of the Buddha image was just one artistic innovation among many. Inquiries into Buddhist responses to new types of image production and use must necessarily be set against the background of a larger expansion in cultural practice. Yuvraj Krishan has pointed to scholarship that suggests that the first Buddha images were a response to doctrinal changes brought about by developments in the Mahāyāna traditions.10 I think it is worth considering that the reverse may well be true, that doctrinal shifts, Mahāyāna or other, were a direct response to broad changes in culture and artistic practice, which the more established doctrinal positions struggled to condemn, excuse, justify, or champion.

Yet even to identify such images as “art” opens us to potential problems. The meanings and associations that most modern readers attribute to the designation “art” are hardly adequate to capture the full range of associations and qualities given to figural imagery in early South Asia. “Art” now typically references visual displays intended to be viewed in acts of leisure or contemplation and, perhaps, containing meanings emblematic of the ideas or values of their creator. Rarely were figural images in South Asia understood as being so passive. Certainly, as works of human creation the images discussed in this book can be seen as reflective of their age and as embodying the priorities of their creators, but to limit ourselves to this perspective would be to miss a very salient point. From the very outset of the figural tradition, images in all South Asian contexts were attributed with a remarkable degree of power, agency, and authority. Any notion that these objects were static or ordinary fails to grasp their significance. Although the contexts and circumstances in which images were believed to exhibit these active qualities vary from case to case and tradition to tradition, it is important to keep in mind that such images were always understood to possess the potential to affect the world around them. This should be our starting point.11

OVERVIEW

The questions that lie behind this book derive from a simple dichotomy. On the one hand, first- to second-century CE Buddhist texts present characters, such as the young monk Vakkali or King Prasenajit, who cannot bear to be away from the Buddha’s edifying image.12 Likewise, this literary material also includes doctrinal texts that extol the many merits of image-related patronage and use.13 On the other hand, texts with equal claim to the label “Buddhist” insist that any devotion to the Buddha’s image is irrelevant, or grudgingly concede that such practices are perhaps slightly better than worthless.14 Other texts even go so far as to insist that images of the Buddha cannot be made at all because the Buddha’s body inherently eludes any manner of depiction.15 These ideological positions bookend a complicated range of perspectives and doctrinal permutations, each of which claims to speak from a privileged position in relaying the intentions of the Buddha. Almost without exception the textual sources make assertions regarding the accurate and eternal nature of their viewpoints, despite the fact that these claims directly contradict or countermand statements made by others who also claim to speak for the same broad religious community.

The task of this project, then, is to attempt to understand and contextualize these divergent points of view while preserving their multitude of opinions. To do so, it will help to set out a conceptual framework so as to avoid potential misunderstanding.

From the outset, any historical study of changes in South Asian image-based practices must address the developments that occurred from the first century BCE to the second century CE, and confront the remarkably formative and innovative nature of that period, when modes of artistic production and religious devotion began to change in profound ways, and many groups were experimenting with new forms of image-based worship. At times I have described this change as a “shift,” but the situation was not as simple as this term might suggest. Rather, what we see is an expansion of artistic and devotional options without the displacement of older ideas. A new layer of cultural practices began to compete with and overlay—but never entirely replace—older ideas. If anything, the new contexts in which figural imagery began to appear forced the older traditions to defend their positions in a manner that, for the first time, clarified their views within the historical record.

This competition between perspectives also introduces the issue of authority, which necessarily runs as a subtext through any discussion of change in religious practice. In some cases, primarily among the more traditional elements within Buddhist and Brahmanic communities, authority is bolstered by inaccessibility, distance, and specialized knowledge, as exemplified by the Brahman elite, who are defined by their birthright and exclusive ritual knowledge, or by the śramaṇa, renouncer, whose ascetic practices and separation from society serve as markers for spiritual potency. An alternate model for religious authority found in South Asia is characterized by its transparency and access. The settled monastic community that welcomes visitors of all social levels, the local caitya dedicated to a regional deity, and the temple complex in which the community gathers for all manner of occasions are characteristic of a model of authority that appeals to the public through inclusion rather than mystery. In short, there are both esoteric and exoteric modes of authority at work.

Naturally, neither of these approaches is entirely exclusive of the other, but as a conceptual framework it can be useful to see the way that various authors and schools of thought have framed their own claims to authority. My hope is that these conceptual categories might be used to underpin the discussion of religious difference rather than reducing it to the charged and tired categories of “high” and “low” religion—an outdated hierarchical model that does far more to muddy the waters with value-laden terminology than it does to help clarify the social dynamics at work.

South Asian image use, for example, particularly in it earliest phases, appears to have had connotations of worldliness rather than spiritual transcendence. This characterization does not, however, mean that these were “low” practices. Indeed, there is every indication that all levels of society had recourse to image-related practices when pursuing worldly objectives. These practices were only occasionally exclusive, and are marked as distinctive primarily due to their functions rather than to any inherent value. Certainly some of the historical sources do seek to impose their preferences and either valorize or denigrate specific approaches to worship, but to side with one set of sources at the expense of others would be to intentionally skew our view of the larger issues. I would prefer to be as specific as possible in recognizing the polemics at work in the literature without getting drawn into the fray.

However, debates in the early centuries of the Common Era are not the only ones to have affected our understanding of early Buddhist art. More recent scholarly studies have also influenced the way we understand the history of Buddhism in South Asia, and chapter 2 examines some of the major issues, ideas, and controversies that have shaped academic discourse on this subject. This historiographic analysis sets the stage for the rest of the book by identifying the major questions and clarifying the methodological approach.

Chapter 3 begins the study by focusing on those strands of thought that express aversion to the idea of image use....