![]()

1

RE-INKING THE NATION

Jackie Ormes’s Black Cultural Front Comics

In the studio of Jackie Ormes, one of the few women cartoonists, the popular comic strip characters of Torchy and Patty-Jo literally spring to life. Syndicated in scores of [Black] newspapers, her cartoons reach more than a million readers each week. Fashion minded youngsters especially like Torchy togs, the cut out section of the comics. [Ormes’s most] famous [creation is] the Patty-Jo doll. One of the nation’s first, Patty-Jo is . . . favored in America as the ideal Negro-type doll——a cute playmate that has brought happiness to many of youngsters. Happiness is her trademark.

—One Tenth of a Nation, an American Newsreel film

[Jackie] Ormes was interviewed by Bureau Agents on May 5, 1953, and July 29, 1953. At these times, she was cooperative and furnished information regarding her front group activities and affiliations, but denied Communist Party membership.

—“Zelda Jackson Ormes,” Federal Bureau of Investigation

IN a 1940 multipanel comic strip, cartoonist Jackie Zelda Ormes illustrates the challenges of Black women artists and the dismissal of their talent by fusing the discourses of elite artistic spheres with the production of sequential art.1 The comic strip presents a Black woman who bears Ormes’s own likeness in a seemingly traditional art class as she faces her white art instructor, Mr. La Gatta. He asks if she is trained or “just a natural born artist.” She answers with a chipper riposte: “Oh sure, Mr. La Gatta—my folks say I’m positively a ‘natural.’ Where’s my easel?” One might view the phrase “natural born artist” as a compliment, but lack of formal training is often used to deny artistic legitimacy, and for some critics it signifies a lack of sophistication and refinement. Ormes’s art student quickly learns this lesson and catches on to the instructor’s veiled insult.

1.1 Jackie Ormes, “Comic Strip Sketch” (n.d.). Courtesy of the Dusable Museum of African American History, 740 E 56th Pl, Chicago, IL 60637.

In the next panel, a view of the class is illustrated, and the art student sits down at her easel to draw, but she begins to sweat profusely. Ormes writes “scrub” in the interior of the panel. In the final panel, Ormes depicts the protagonist in front of an easel, where she is drawn three times smaller than in previous panels and the chair she sits in is disproportionately large. Ormes relates through self-deprecating humor that the art instructor has sought to make the protagonist “feel small” by belittling her art and therefore belittling her as a creative woman and human being. She uses humor to convey her point about the marginalization of Black female artists, but the implications of her message reflect a serious stance that is echoed in an elitist artistic imaginary, which is ultimately upheld by Mr. La Gatta’s final comments. Mr. La Gatta, with a sinister grin, looks down at the Black female student and the cartoon figure she has drawn on her easel, and exclaims condescendingly: “Hm-m-m-m. You may have it, little lady, but for the present I’d say it’s still unexpressed!”

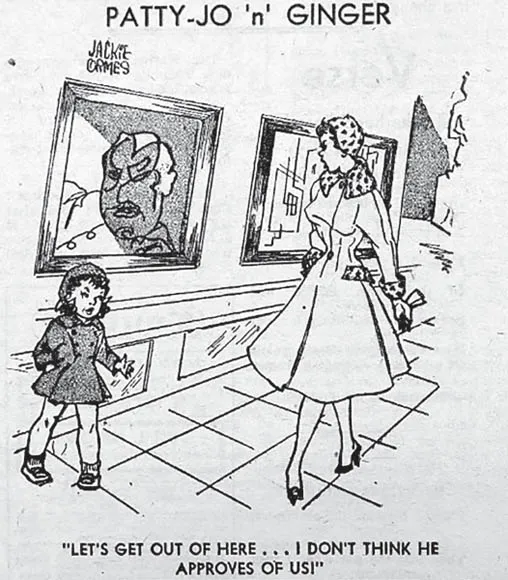

Ormes returns to the theme of comic art within traditional art spheres in her Pittsburgh Courier gag Patty-Jo ’n’ Ginger (December 17, 1955). Here, she pictures a finely dressed young girl (Patty-Jo) and her older sister (Ginger) walking through an art museum. On the wall of the museum are a series of abstract paintings, one of which looks strikingly similar to the work of Pablo Picasso in the late 1930s. At the time, Picasso had made a shift in his artwork from detailed realism to modernist images of fragmentation and the divided psyche.2 This thematic shift is replicated in the painting in Ormes’s gag, in which an abstract male profile hangs on a rectangular, descending wall; the man’s face is divided by sharp lines and haphazard doodles. Patty-Jo and Ginger, aesthetically at least, appear to belong in the space they inhabit; their clothing, style, and class performance is congruent with the idea of museums being public spaces of distinguished taste. Yet, the Picasso-esque painting that glares at them disapprovingly signals that despite their assumed class status, the larger art world looks down on the two and questions their presence in the museum. Indeed, while returning the painting’s look of disgust, Ginger exclaims, “Let’s get out of here . . . I don’t think he approves of us!” In these comic strips of the 1930s and 1950s, Ormes expresses an artistic struggle that constitutes more than the exposure of ongoing racism in the art world. She raises the question of whether or not comic strips have a place within the art world as a whole.

1.2 Jackie Ormes, Patty-Jo ’n’ Ginger, “Let’s get out of here. I don’t think he approves of us!” Pittsburgh Courier, December 17, 1955. Courtesy of Nancy Goldstein.

To vie for a position within the field of elite art may constitute an ideological intervention for comic artists, but it is ultimately a fool’s errand. I thus argue throughout this book that comic art is significant for its ability to appeal to everyday life and culture given its unique ability to combine image, text, space, action, and humor with the intent to communicate a pithy, powerful message to a reader or spectator. As a form of sequential art, comic strips and gags (single-panel comics) inform on culture and sometimes on politics and mediate or complement the content in the newspaper on the pages before and after their appearance. Equally important, comic strips and gags may provoke laughter and visual fun. The strategic insertion of the comics, fondly referred to as “the funny pages,” serves as an ancillary component to the dense contents of the rest of the newspaper. While many may find these pages a form of harmless comic relief, cartoonists of the present and past have faced censure and surveillance for the political leanings of their work. Contemporary comic artist Aaron McGruder experienced censure for his political position on 9/11 in his comic strip The Boondocks in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks. After running a series of strips in which he insinuated a connection between the Taliban and the administration of former president Ronald Reagan and his vice president, George H. W. Bush, local and national newspapers pulled the strip from the funny pages.3

Eight decades earlier, cartoonist and journalist Ormes had paved the way for McGruder’s artistic defiance. Ormes created art that was ostensibly funny, but her activism and her work’s focus on social justice seemed to create few laughs among Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) operatives, who considered Ormes subversive and a potential threat to the security of the nation. Ormes’s early childhood years, her short career as a journalist, her struggle as a comic artist, and her experience of being under surveillance by the FBI—which suspected she was a member of the Communist Party—frame the diverse aspects of her comic art.

Jackie Zelda Ormes (whose birth name is Zelda Mavin Jackson) was born August 1, 1911, in Pittsburgh and raised in Monongahela, Pennsylvania.4 Government documents claim that after high school, Ormes attended Salem Business College and, later, art school in Pittsburgh, though family members and recent accounts speculate on the veracity of that continued education.5 Though she had not trained as a cartoonist when she began penciling comics in the late 1930s, Ormes did study at the Commercial Art School in 1945 and the Federal School of Cartooning years later.6 Ormes’s father was a store owner and pastor, and her mother was an expert seamstress. Her solid upper-middle-class background situated Ormes among the Black Professional Managerial Class (BPMC) of the early twentieth century, a class enclave within the Black community that would negotiate the pulls of class ascension with respectability, uplift, and reform efforts in their communities. Ormes married in 1933 at the age of twenty-two and began her career in news media as a proofreader for the Pittsburgh Courier. Although she had applied for a position as a reporter, the glass ceiling of the times limited her to subordinate secretarial duties, and only on occasion did the paper’s publisher, Robert L. Vann, allow her to report on stories concerning culture, sports, or fashion.7

Historian Alice Fahs has written about the prospects for women in journalism at this historical moment: how they faced a glass ceiling, income disparity, and an overall lack of equal opportunity. In the late nineteenth century through the early twentieth, the number of women in big cities making their living as reporters or as journalists increased rapidly, from 2.3 to 7.3 percent. However, compared to their male counterparts, women worked on space rates (i.e., compensation for units of work), rather than on salary, requiring them to strive for extraordinary achievement beyond their male peers’ efforts in order to earn a decent wage and remain active in the profession. To assuage the gender-equity discomfort of their male supervisors and peers, and to appear less threatening, female reporters were inventive and strategic about their space rate assignments.

The plight of Black women in newspaper reporting and journalism was, of course, a double form of discrimination that their white working-class sisters did not experience. Despite gender discrimination, there were no “absolute barriers to working-class [white] women on mass circulation newspapers,” writes Fahs, but “there were . . . absolute (if unstated) barriers to African American women on the major metropolitan newspapers.”8 Early Black activists and newswomen in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Mary Church Terrell, Victoria Earle Matthews, Fannie Barrier Williams, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, and Gertrude Bustill Mossell, were shut out of reporting for and sparingly afforded a voice in mainstream metropolitan newspapers, making the emergence of Black newspapers ever more important.9 Black journalist Clarence Page, who came of age in the 1950s, writes of the role of Black newspapers:

The Pittsburgh Courier, the Michigan Chronicle, the Chicago Defender, and the Cleveland Call & Post . . . offered something the big white newspapers left out: pictures and stories about black doctors, lawyers, politicians, business folk, society ladies, church leaders, and other “Negroes of quality.” . . . The comments and cartoons in the colored newspapers had a mission to bluntly and reliably ridicule anyone perceived as standing in the way of black progress. . . . The Negro press gave African Americans something no other media were ready or willing to offer: visibility and a voice.10

Ormes had as predecessors women such as the antilynching activist Ida B. Wells, who in 1892 moved from an editorial position at the Black newspaper the Evening Star to co-owner and coeditor of her own newspaper, the Free Speech and Headlight, which reported on the horrors of racism and segregation. Yet Robert L. Vann’s assignments to Ormes show that Black newspapers also engaged in gender discrimination in their leadership and the opportunities they offered women for meaningful reporting assignments. Ormes’s disappointment and the gender bias of the day ironically led to the birthing of Black women in comics. Her lack of opportunity as a reporter at the Pittsburgh Courier led her to reinvent herself as a news-woman by reporting through the visual and print form of comic strips.

Historian and cartoonist Trina Robbins has traced the work of white women cartoonists, arguing that, initially, white women experienced autonomy in the field. Nell Brinkley worked with success for the Hearst syndicate in 1907. Other established cartoonists, such as Grace Drayton, Kate Carew, and Marjorie Organ, preceded her; they shared an illustrative aesthetic of cartooning young children as innocent, cherub-type caricatures.11 Brinkley perhaps experienced the most success and broke away from the standard representation of apple-cheeked children with her creation of the independently minded Brinkley Girl, a comic strip counterpart to Charles Dana Gibson’s Gibson Girl published in LIFE magazine in the late nineteenth century. The Gibson Girl was a popular pencil illustration of refined, ephemeral womanhood. Art historian Maria Elena Buszek writes that the Gibson Girl was a mixture of contradictory signs: sexual yet not lewd, assertive yet ordinary, masculine yet hyperfeminine, upper-class yet still the personification of the girl next door.12 By contrast, the Brinkley Girl was working class and headstrong; Brinkley’s illustrations influenced young women to draw inspiration from and replicate this New Woman characterization.

World War II offered opportunities for more white women cartoonists as male cartoonists enlisted or were drafted into the military, but by the 1960s, the number of female cartoonists had dwindled significantly in part because of the popularity of superhero comics and the solidification of the field as a male arena. Robbins charts a history of white female comic strip artists and writers that defies a declension narrative and shows their experiences as a fluctuating narrative, like history itself—one moving from progress to mishaps to progress again. In the early twenty-first century there are more female cartoonists and comic book artists and writers than in yesteryear, but their visibility is still lacking in comparison to their male counterparts. It is in the larger context of women cartoonists in the nineteenth century that one might contemplate the significance of the bravery, tenacity, and longevity of Jackie Ormes in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.

Jackie Ormes and Black Cultural Front Comics

Ormes created four strips throughout her life as a cartoonist. Her gag Candy focused on a witty and glamorous domestic who signified on the woman she worked for while bringing a new voice to Black women in domestic service. Ormes’s comic strip Patty-Jo ’n’ Ginger used the voice of a young girl to challenge segregation, sexism, and racism in the late 1940s through the mid-1950s. Ormes’s first and last strip, Torchy Brown, focused on a young woman who leaves the South to realize her dream career by becoming a showgirl and singer at New York’s Cotton Club. Torchy’s comic strip life and world are full of cultural and racial roadblocks, economic mishaps, gender politics, and sexual adventures—a daring subject for any woman cartoonist in the 1930s. Torchy Brown ended in 1938, but Ormes resurrected it in the 1950s, this time making Torchy a middle-class nurse and environmentalist. The new version of the strip, renamed Torchy Brown: Heartbeats, ran until 1954, when Ormes retired from cartooning. Later in her career, her hands became crippled by rheumatoid arthritis and she worked as a doll maker. Both incarnations of Torchy Brown seemed closely aligned with the experiences of the real-life Ormes, who left the comforts of a small town to work in the uncertain environment of a metropolis. While working for the Courier and the Chicago Defender, Ormes became increasin...