![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE SON OF IMMIGRANTS, BUT ALL-AMERICAN

LIKE THOSE OF MANY AMERICANS, FRED’S SPIRIT, HOPES, AND dreams grew from the spirit, hopes, and dreams of immigrant parents. His father, Kakusaburo Korematsu, was born in Maibara-machi, Fukuoka, Japan, on June 11, 1876. The late 1800s were hard for farming families like his, and, just after the turn of the new century, Kakusaburo joined the wave of young men leaving Japan in search of greater opportunity. Lured by the prospect of work on the sugar plantations of Hawai‘i, at the age of twenty-eight, he boarded the SS Doric in Yokohama on October 8, 1904. The ship’s manifest listed Kakusaburo’s occupation as “farm laborer,” the same as every other young man on that ship.1

Kakusaburo made his way to the island of Kaua’i and became part of the Issei, or first, generation of Japanese in this country; he did not, however, last long there. Housing was poor, compensation was meager, and working conditions were often abusive. News of higher wages beckoned workers to the mainland United States, and on April 26, 1905, less than a year after his arrival, Kakusaburo headed to San Francisco on the SS Alameda.2

Life on the mainland, however, would not be easy, either. Even as the country sought Asian immigrants as cheap labor, it did not welcome them. Arriving Issei recalled being called “Japs” or “Chinks” and being pelted with rocks and spat upon.3 The refrain that Japanese Americans were different and foreign, and thus a race not capable of being American, began with their arrival in this country, grew in intensity, and ultimately became integral to the call for their mass incarceration decades later. That refrain had early expression in comments like those by San Francisco Mayor James Duval Phelan, who, in May 1900, addressed the first large-scale protest against Japanese in California: “The Chinese and Japanese are not bona fide citizens. They are not the stuff of which American citizens can be made…. Personally we have nothing against Japanese, but as they will not assimilate with us and their social life is so different from ours, let them keep at a respectful distance.”4 Phelan’s comments ignored, however, that any failure of Japanese Americans to assimilate was not truly of their own choosing. Their social isolation was largely externally imposed. Racism, discriminatory practices, and laws that denied them the incidents of full citizenship excluded them from mainstream society.5

The popular press warned of the “yellow peril” that Asian immigrants posed to the country and fanned the flames of racism.6 In May 1905, delegates from sixty-seven organizations met in San Francisco to form the Asiatic Exclusion League, arguing for the exclusion of Japanese as threats to white society and its economic well-being: “We cannot assimilate with them without injury to ourselves…. We cannot compete with a people having a low standard of civilization, living and wages…. It should be against public policy to permit our women to intermarry with Asiatics.”7 The exclusionists won an early victory when, in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt barred further Japanese immigration from intermediate points in Hawai‘i, Mexico, and Canada. That victory became more complete when Roosevelt’s “Gentlemen’s Agreement” with Japan banned all further immigration of Japanese laborers.8

Despite the animosity toward them, the Issei endeavored. Economic opportunities, however, were limited. While there was a demand for low-wage laborers, racism and exclusion in the labor market denied the Issei access to other, better jobs. Many took their entrepreneurial spirits and became shopkeepers, merchants, and small businessmen. Kakusaburo was one of those entrepreneurs. In later years, Kakusaburo’s daughter-in-law, Kay Korematsu, described him as having both an easygoing manner and an air of confidence—even conceitedness and recklessness—and these traits likely served him well as he struck out on his own.9

Kakusaburo started a flower nursery in an industrial area of East Oakland, across the bay from San Francisco, joining a vibrant community of Japanese immigrant families who had found a niche in the West Coast flower industry. While most of these Issei had no experience growing flowers, their ingenuity, innovation, and hard work combined to make them important players in the business.10 Property records suggest that Kakusaburo purchased the land for his nursery in 1913, before the effective date of the state’s Alien Land Law. That law, which went into effect August 10, 1913, prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from purchasing property or entering into long-term leases on agricultural land. Because the Issei were barred from citizenship, the law prevented them from owning the land they worked. Kakusaburo likely obtained title to his nursery just under the wire.11

Kakusaburo’s nursery soon became a going concern. His thoughts turned to marriage and family, and he sent for a bride. While the Gentlemen’s Agreement had stopped the flow of male laborers from Japan, women could still enter to join them. Some men returned to Japan to find a bride or to bring a wife they had left behind, but most, lacking the financial means to travel, sent word to their families that they would like to marry, and their families found them brides to join them in the United States. Thus began the emigration of large numbers of “picture brides” to America—a system of “photo marriages,” or shashin kekkon, which developed naturally in a country where marriages were routinely arranged by family. While, in a traditional marriage, or omiai kekkon, a go-between would facilitate the match, a meeting would be arranged, and a ceremony held, those formalities were not essential to a legal union. Instead, a marriage was legal when the bride’s name was entered into the husband’s family register, making her a member of his household. The extension of the practice of omiai kekkon thus allowed young men like Kakusaburo to marry brides who then joined them in their new land.12

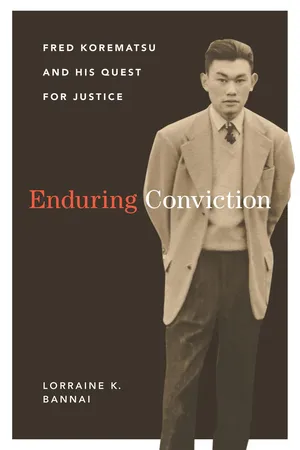

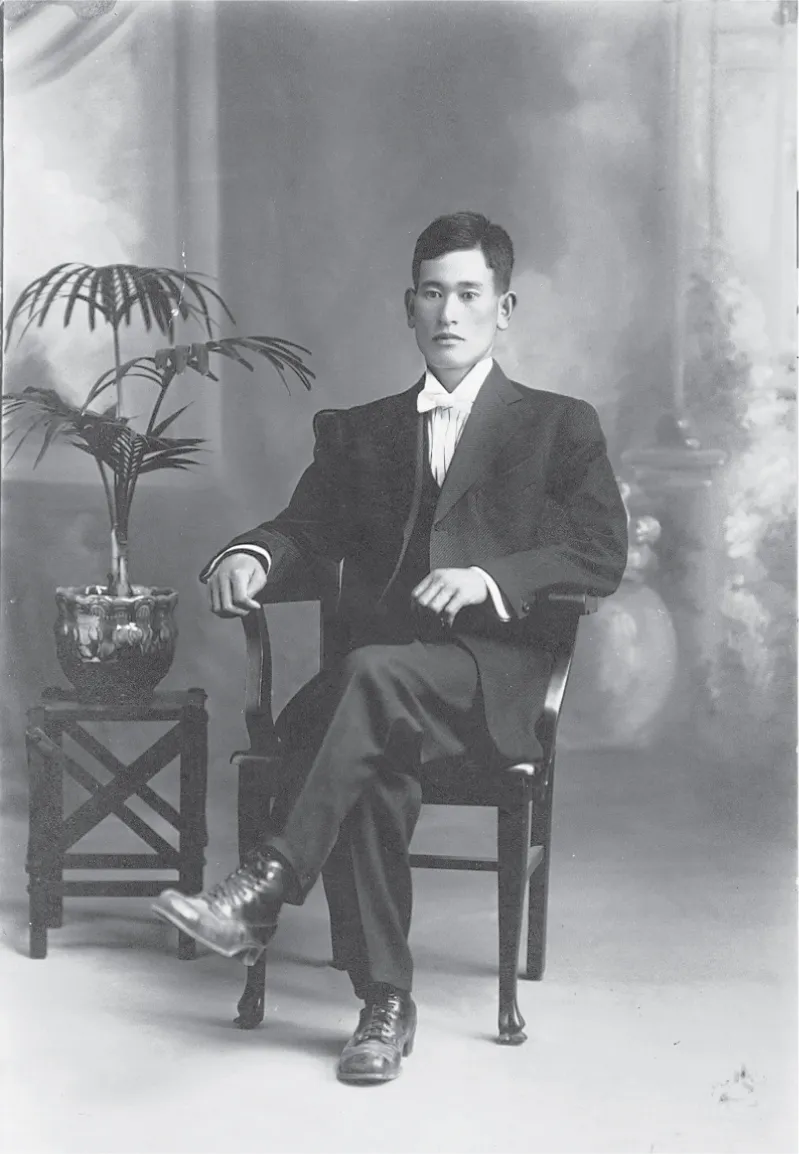

Kotsui Aoki was from a farming family in Kakusaburo’s home town of Maibara-machi and married him in Japan on August 11, 1913, although he was not present. Never having met her new husband, and bound for a country she did not know, she made the long trip to the United States on the SS Siberia, arriving in San Francisco on January 12, 1914. It’s not possible to know what was in Kotsui’s heart and mind as she prepared to travel across the Pacific; her daughter-in-law, Kay Korematsu, recalled Kotsui saying that she arrived excited to live in America. On her arrival, Kotsui met someone very different from herself. Kakusaburo was thirty-seven years old; she was twenty-two. In portraits submitted with Kotsui’s immigration application, Kotsui is serene—dressed in a beautiful kimono with her hands neatly folded in her lap. Kakusaburo cut a dapper, contrastingly modern figure in his black suit, white shirt, and polished shoes. She, having been a teacher in Japan, was more educated than her husband-to-be.13

FIGURE 1.1. Fred’s mother, Kotsui Korematsu, on her arrival in the United States, circa 1914. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration at San Francisco.

FIGURE 1.2. Fred’s father, Kakusaburo Korematsu, circa 1914, included as part of Kotsui Korematsu’s immigration file. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration at San Francisco.

At Kotsui’s entry interview at the immigration station on Angel Island, California, in January 1914, Kakusaburo stated that he had little money, but the Japanese Consul certified that “he [was] a man of good character, and [had] means to support his family.” Because the “photo marriage” was not recognized in California, Kotsui was admitted to the country on the condition that she and Kakusaburo marry lawfully. The day she was released from Angel Island, January 15, 1914, they were married again by a Buddhist minister.14

Seeing Japanese continue to immigrate, anti-Japanese activists intensified the call for their exclusion, including the exclusion of picture brides and denial of citizenship, even for second-generation Japanese Americans born on U.S. soil.15 In March 1924, the influential former publisher of the Sacramento Bee, V. S. McClatchy, and others carried the exclusionist banner to Washington. In testimony before the Senate Committee on Immigration, McClatchy argued the now-familiar “yellow peril” refrain, warning of the economic threat the Japanese posed to the nation:

Of all the races ineligible for citizenship under our law, the Japanese are the least assimilable and the most dangerous to this country…. They come here specifically and professedly for the purpose of colonizing and establishing here the proud Yamato race…. In pursuit of their intent to colonize this country with that race they seek to secure land and found large families…. They have greater energy, greater determination, and greater ambition than the other yellow and brown races ineligible to citizenship, and with the same low standard of living, hours of labor, use of women and child labor, they naturally make more dangerous competitors in an economic way.16

The Nikkei were hardly the threat that McClatchy portrayed them to be. By 1930, there were 97,456 Nikkei in California, representing only 2.1 percent of the total population of the state, and only .10 percent of the population of the continental United States.17 Nevertheless, the fight to end Japanese immigration—another significant step in the exclusionist’s cause—was finally won: on June 30, 1924, Congress completely banned the immigration of any “alien ineligible to citizenship.” Despite the seemingly neutral phrasing of the prohibition, it was clear that the ban was enacted to bar further immigration from Japan.18

The Nikkei, however, could not be deterred by the anti-Japanese vitriol that sounded in the chambers of government. They had, after all, no voice in those halls and had to attend to their livelihoods. Through hard work over long hours, Kakusaburo and Kotsui established a successful business; their greenhouses bloomed with Bouvardia, roses, and, later, carnations. And their family grew with the birth of four boys. As part of the Nisei, or second, generation, all of the boys were born American citizens. The Japanese names that Kotsui and Kakusaburo gave them were shed as cumbersome as the boys ventured out from the family home. Hiroshi, the first born, came to be called Hi. Takashi, the next, later went by Harry. The youngest, Junichi, was later called Joe. Fred was born on January 30, 1919, with the given name of Toyosaburo, “saburo” meaning “third son.” Fred’s elementary school friends called him “Toy,” as Toyosaburo was more than they could handle. One of Fred’s early teachers, who also found his name too hard to pronounce, asked if she could give him another name. She asked, “How would you like to be called ‘Fred’”? He had a friend named Fred and liked the name, so he agreed and used that name for the rest of his life.19

In school, Fred acquired more than an American name. He learned what it meant to be an American, and those lessons resonated deeply with him. The United States was the only country he knew, and he was proud of his country. Years later, he recalled, “When I was in school, we started each day with the pledge of allegiance to the American flag. I studied American history and the Constitution of the United States and believed that persons from in this country were free and had equal r...