eBook - ePub

An Affair with Korea

Memories of South Korea in the 1960s

Vincent S. R. Brandt

This is a test

Share book

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Affair with Korea

Memories of South Korea in the 1960s

Vincent S. R. Brandt

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In 1966 Vincent S. R. Brant lived in Sokp'o, a poor and isolated South Korean fishing village on the coast of the Yellow Sea, carrying out social anthropological research. At that time, the only way to reach Sokp'o, other than by boat, was a two hour walk along foot paths. This memoir of his experiences in a village with no electricity, running water, or telephone shows Brandt's attempts to adapt to a traditional, preindustrial existence in a small, almost completely self-sufficient community. This vivid account of his growing admiration for an ancient way of life that was doomed, and that most of the villagers themselves despised, illuminates a social world that has almost completely disappeared.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is An Affair with Korea an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access An Affair with Korea by Vincent S. R. Brandt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia coreana. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia coreana1

Sŏkp'o 1965–1966

I always had a sense of calm well-being waking up in Teacher Yi's guest room with its uncovered wooden beams and whitewashed mud walls. In addition to the wood smoke from the cooking and heating fires, I could smell the dried fish, garlic, sesame seeds, red pepper, and grain in the storage space next door. The guest room had no windows, but had four small paper-covered doors let in a soft, early morning light. Consciousness came gradually along with the low, rhythmic sound—more of a vibration—of the ox munching beyond the other side of the wall by my head. The morning fire that heated the ox's mash also warmed my floor through the system of stone flues that made old Korean farmhouses so wonderfully snug in cool weather. More warmth came in with the spring sunlight when I opened the doors. Then I would crawl out onto the wide, polished boards of the veranda, savoring the only real privacy of the day.

The guest room, or sarangbang, along with the unfinished storage space next to it, formed the southern side of the house. A fuller translation of sarangbang would be the outer room of a larger farmhouse that serves as an informal meeting place for influential or older men in the neighborhood. There was no furniture in this room. Thin reed mats were placed directly on the uneven, dried-mud floor. They served as cushions during the day and as a mattress at night. The sarangbang was the only room with direct access to the outside, and men could gather there without entering the courtyard of the house and disturbing (or being disturbed by) other members of the owner's family. My room continued to be the neighborhood sarangbang, and men would gather there without warning to talk and smoke and drink at any time from 10:00 a.m. until 10:00 p.m., staying on sometimes well past midnight. Although eventually I understood (and this took a few days) why my bedroom was being constantly invaded by elderly gentlemen who sat talking for hours about genealogies and tomb sites, I never really got used to it.

The other three sides of the house, comprising family quarters, the kitchen, toilet, chicken house, ox stall, and tool shed, all opened onto an enclosed courtyard, protected from the outside world by an imposing wooden gate. In back, against the hillside, was another small enclosed yard, the exclusive domain of the women.

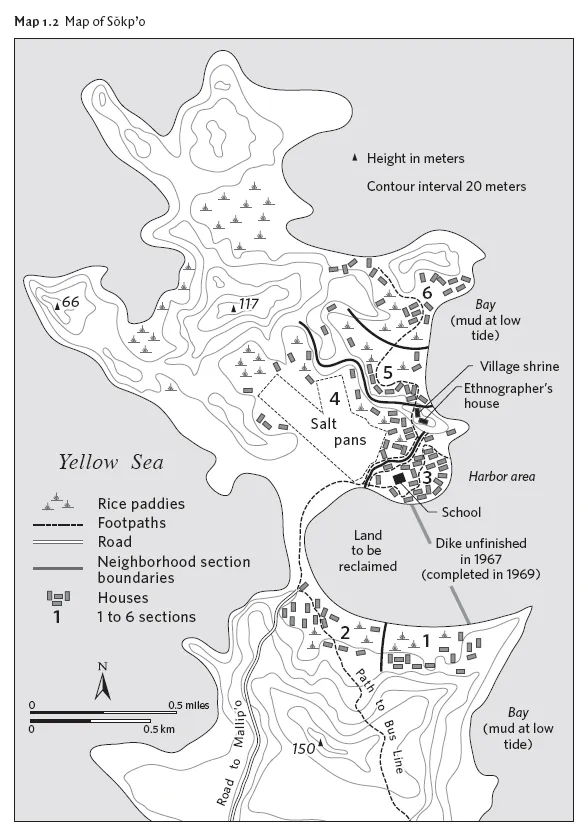

On my side of the house, to the south, I looked out onto a broad, ochre-colored dirt threshing ground and a gently leaning thatched shed covering the night soil storage pit, which doubled as my private toilet. One hundred and fifty yards or so beyond the night soil pit, at the base of a steep wooded hillside, was a clear stream where women gathered to wash clothes. To the east the land sloped down for a couple hundred yards past some other houses and then flattened out into terraced rice fields that stepped gradually down to the bay. An old stone dike separated the lowest fields from the mudflats that were covered by salt water at high tide.

I could get a pretty good idea of the outdoor activities of a substantial portion of Sŏkp'o's population just by standing outside Teacher Yi's house and looking out over the nearby fields and across the mud or water. By the time I was off the veranda brushing my teeth, Kim P'albong, Teacher Yi's live-in agricultural worker, would already be up and carrying heavy buckets of night soil out to the cabbage and pepper plants.

Teacher Yi's cousins and second cousins and third cousins and uncles and uncles once removed who lived nearby were also out working in their fields, even before their wives had lighted the kitchen fires for breakfast. Down on the mudflats, if it was low tide, there were usually a couple of men digging for octopus while children gathered snails and clams. A little later, work would start on the dike. The purpose of the dike was to seal off an arm of the bay and create new rice fields. Villagers with no other employment slowly carried their loads of rock and dirt on pack frames out to the wide unfinished portion of the dike and dumped them into the gap, only to have everything washed away by the next tide.

From my vantage point I could look north across the half mile of mudflats (at low tide) or water (when the tide came in) to the “Big Hamlet,” a tightly packed cluster of forty-five houses by the harbor. If the gap in the dike were ever closed, these mudflats would become rice fields. When the fishing fleet was in, I could usually see eleven or twelve sailing junks drawn up on the beach or bobbing around at anchor just offshore. The coming and going of the boats was mysteriously irregular, depending on the state of the tide, the weather, the season, and the whim of the fishermen. The Big Hamlet, along with the two smaller, dispersed hamlets at the northern tip of the peninsula, was connected to the mainland by a narrow grass-covered sandspit bordering the ocean. This sandspit was out of sight to my left behind a shoulder of the hill, but I could hear the waves breaking on it in rough weather. Beyond the Big Hamlet, the peninsula, now almost an island, spread out to encompass white-sand beaches alternating with rocky cliffs on the ocean side, while wooded bluffs or rice fields bordered the bay. More or less in the middle of this presque isle there was another towering hill or small mountain. The land rose gradually, with open fields giving way to pines as the slopes steepened. The villages across the bay to the east were so far off that I could just barely make out their boats and houses on a clear day. In that direction it was usually only possible to see hills and mountains, sharply silhouetted in the morning but turning to hazy purple as the day wore on.

I was in South Korea to carry out social anthropological research to decipher the customs, value system, and social structure of a small community using the “sympathetic participant-observation” method. Having already spent eleven years in the diplomatic service (two of them in Korea), I was now in a fishing village as an over-age graduate student, trying to earn a doctoral degree and launch a second career. My somewhat vague objective on the Korean Yellow Sea coast was to compare and contrast the experiences and personalities of farmers and fishermen. A number of studies throughout the world and my own previous experience in Japan had suggested that fishermen tend to be bold, swaggering risk takers, less bound than landsmen by the conventions and values of a society's mainstream ideology. Farmers, on the other hand, were, according to this simplistic hypothesis, more likely to be careful conservatives, concerned with preserving tradition and maintaining the status quo. Sŏkp'o, with its mixture of farming and fishing households, seemed an ideal place to test such a theory. My personal reasons for picking a village on the ocean were probably more compelling: I like the ocean, coastal scenery, boats, and seafood.

But it had taken me a long time to find the right place. South Korea has an enormously long coastline. For several weeks I roamed both the east and west coasts of the Korean peninsula by bus and on foot. I stayed in country inns where they were available and in farmhouses where they were not. There were exotic bugs, filthy toilets, stomach trouble, strange bedroom companions, and extremes of heat and cold. Privacy was almost nonexistent. In most places I was more than just a peculiar object of curiosity; I was the most entertaining event that had come along in weeks. In areas where American troops had once been stationed, children would crowd around yelling, “Hello!” and asking for candy and cigarettes. Almost always there was at least one high school student who wanted to practice his English. Old people would come very close to examine me, sometimes pulling at the blond hair on my forearm to see if it was real.

In Korea hospitality has always been a moral obligation, a matter of individual and community pride. Without fail someone would make sure that I was fed and had a place to sleep. And no one, except innkeepers, ever took money for a night's lodging. In return I was subjected to public scrutiny and intensive questioning about America and the outside world. There seemed to be no end to the villagers' desire to break out, even momentarily, from the constraints of rural life.

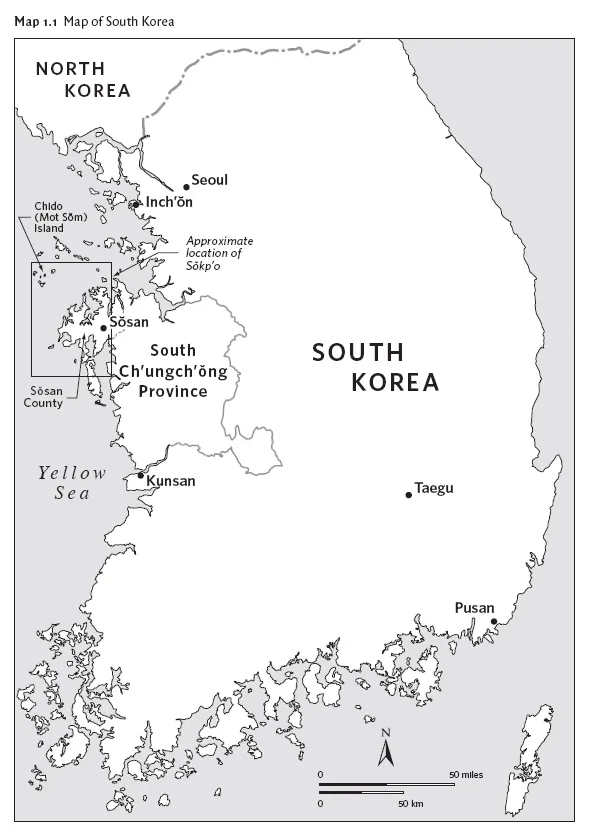

As a result of all my wandering, I finally narrowed the search for a research site to a portion of the Yellow Sea coast in South Ch'ungch'ŏng Province. This is the part of South Korea that sticks out the farthest into the Yellow Sea towards China. Here, there is fairly deep water right up to the rocky shore, so small boats have easy access to offshore fishing. At most other places along Korea's west coast, where the tidal range is over twenty feet, miles of mudflats extend far out from shore except at high tide. In 1966, the whole region, which has a wildly indented coastline, was isolated and undeveloped, with few roads. This appealed to my sense of adventure. I also hoped that the isolation would allow me to find a relatively traditional community.

A Korean friend in Seoul who had formerly been a minister in the government heard about my plans and offered to introduce me properly to the local county magistrate in Sosan, the county seat. My friend had a colleague, another former minister, and together they enthusiastically proposed a joint expedition to help me get started with my fieldwork. It was time, they said, to get away from Seoul and experience the “fresh, robust pleasures of country life.” They told me that from ancient times men of good character and high position had periodically left the corrupting influences and materialistic temptations of the capital to seek spiritual refreshment in simple, rustic surroundings. Both of these men were cultivated, cosmopolitan members of the South Korean elite. At first I was doubtful about having such high-powered escorts. The last thing I wanted was any sort of official intervention in my work. On the other hand, it seemed like a good idea to square things away with the local authorities right from the start. And in any case, I was curious about those “robust pleasures.”

So we set off in a handsome new Land Rover, complete with driver and baskets full of food and drink. As a rule it took six hours to get to Sosan by train and bus. In our private vehicle we should have been able to do it in three and a half hours. As things worked out, it took two days. On the first day, with only about an hour to go to reach Sosan, we turned off the main road and headed up into the mountains on a dirt track. After a long, rough climb we finally arrived at a handsome compound of several old wooden buildings that looked like the home of a Yi Dynasty (1392–1910) aristocrat. It was a hot spring resort, and it was obvious that we were expected. Two stylish women in traditional dress came out to greet us, flanked by maids and porters. The main building had heavy, curved-tile roofs and massive wooden pillars. Several smaller annexes angled off from it, with the whole compound laced together by paths and small gardens. Plaques with beautifully inscribed Chinese characters proclaiming ancient moral axioms hung over the doors or on corner posts.

We took off our shoes and went inside, where I was amazed to find that each of us had his own room. In the Far East the usual procedure at an inn is for all members of a group traveling together to sleep in the same room. Here, in my own room, the oiled-paper floor shone with a rich brown patina. The hanging landscape scroll and a screen decorated with calligraphy seemed to be of museum quality. In the corner on a delicate stand of persimmon wood, was a Koryo celadon bowl. Brocade cushions invited the tired traveler to take his ease. At the far end of the room was a small double door of intricate geometric lattice work covered with paper. The door opened onto a rock garden and just outside, underneath the broad eaves of the tiled roof, a platform of polished wood provided a place to sit and look at the garden and mountains in the distance. There was a pair of sandals on the ground below, in case the occupant might want to stroll outdoors.

It was all much more luxurious than the finest suite at an expensive international hotel in Hong Kong or Tokyo. The room and its garden had a kind of Arabian Nights quality, as if all the resources of an entire civilization had been dedicated just to pleasing my senses. And yet the dominant theme was restraint, with an emphasis on spare forms and rich, subdued colors. I was encountering an ancient, elite, cultural heritage—not as an exhibit in a museum, but as a welcoming personal environment.

While I was thinking about the extraordinary things that lots of money could still buy in a poor, “undeveloped” country, another elegant woman came in with tea and a registration slip. While she waited, I filled it out, finding considerable satisfaction in being able to decipher the characters and fill in the blanks, even though my writing looked like that of a fourth-grade student. Rising with the sighing sound of heavy silk skirts, she said, “Please go and join your friends in the bath and relax after your hard journey to this faraway place.”

After nearly an hour of soaking, scrubbing, rinsing, and soaking again, we gathered in the room of my friend. It was larger and still more sumptuous than mine. On a low table in the center there were whiskey (real Johnny Walker Black Label), ice, and glasses, along with fifteen or twenty small dishes of hot and cold food. This was the anju, appetizers to accompany drinking. My friends demanded yakchu, the yellowish country beer that is entirely homemade and could no longer be found easily in Seoul. Its name means medicinal spirits, and we drank that instead of the whiskey.

Three attractive young women poured our yakchu and popped delicacies into our mouths. Maids kept bringing more dishes until the round table was completely covered. The drinking phase of the meal went on for quite a while. At first the women served us sedately, while we talked among ourselves. Gradually the mood became more cordial, even a little boisterous, until we finally were pouring reciprocal cupfuls for our female companions. Then the table was partially cleared and a whole new banquet of side dishes was brought in along with rice and soup. I couldn't help remarking ironically about “simple country pleasures.” My friend answered, “You will find out all about those soon enough. Tonight we just enjoy ourselves. You may need some nice memories when you are sharing fishermen's food in a dirty hut.”

After dinner we played a little poker, with the women joining in, and out of the fast, joking chatter I picked up a couple of references to strip poker. I was a little disappointed and confused when one of my friends suggested that it was time to “separate” since it had been a long day and we must be tired. It hadn't been a long day, and I wasn't particularly tired, but there was no way I could prolong the lively party on my own.

In my room bedding had already been spread out on the floor. The thick quilt was made of brightly colored silk with a clean white sheet sewn on the underside. There was a small lamp by the pillow and alongside it a pitcher of cold barley tea. Most of the room was in deep shadow. I was about to take off my clothes when the door opened after a discreet knock and one of the matrons who had originally welcomed us came in. She patted the bedding, rearranged the pillow, checked to make sure there was tea, and asked polite questions about America. She praised my Korean, although we both knew it was terrible. Then she asked me a number of different times in a number of different ways if there was anything else I wanted. Having been spoiled and catered to all evening, I couldn't think of a thing. She seemed to leave reluctantly, after making some more purely ritual conversation, and I wondered if perhaps I had been expected to make some sort of pass at her. But she just did not have the manner of someone in that line of work. In addition to poise and elegance, she had a certain managerial bearing. If not the owner, I was certain that she was at least running things at the inn.

As usually happens after a good deal of liquor, I was wide awake by two in the morning. The only thing that infallibly works on these occasions is to get up, do a few exercises, and drink some water. Then I can get back to sleep without any trouble. I pushed open the door to the garden to find an early full moon. It was cold in the mountains, but I had a bathrobe and the sandals were there waiting. I would exercise outdoors. The moonlight was so bright that I could read the Confucian mottos on the buildings. After some mild calisthenics I wandered along the path, soon reaching the building where my friends were lodged. On the stone step below the veranda of each of their rooms a pair of white women's slippers gleamed in the moonlight alongside the dark men's shoes. I returned to my room, now wide awake. So that was why the matron had lingered! I was supposed to order a companion for the night. Obviously I had failed my first test in “sympathetic participant observation.”

The county magistrate in Sosan, who had been advised of our visit by the Ministry of Home Affairs in Seoul, was graciously attentive when we reached his office the next afternoon. He gave us a formal briefing complete with statistics on local population, rice production, fish catches, and the numbers of middle and high school graduates. He was even able to pinpoint the few coastal villages where a local boy had gone on to college. It was obvious that he was far more concerned with the educational attainments of the people under his jurisdiction than their economic prosperity. He also provided me with a written introduction to a Mr. Koo, who lived in Mohang, the village at the end of the road where it reached the coast.

My friends planned to spend the next night at another resort, but they insisted on first taking me two hours out of their way on a terrible road to reach Mohang and Mr. Koo. I could tell they were worried about just dropping me off in the middle of nowhere at dusk. For them the countryside meant clear air, picturesque villages, and good-hearted, simple people. But these were pleasures to be enjoyed only during the day and then usually from the seat of a car or Jeep. My friends brought their own food, and when they talked to villagers, it was as if they were graciously condescending to bridge an enormous gap between themselves and a slightly different species. Above all, they had no desire to experience the discomforts of rural life at night. By then I was eager to break loose and try getting along on my own, but my generous friends would not leave until they found Mr. Koo and made sure I would be fed and lodged.

At last the Land Rover disappeared, and I was alone in a small, very cold square room with a kerosene lamp for company. In the corner was a roll of bedding that only vaguely resembled the splendid comforter and gleaming white sheets of the night before. This was December, and I had the definite impression that at Mr. Koo's house they changed the sheets once a year, only at New Year's.

The floor of the room warmed up quickly after the fire was lit, and before long a woman brought in a tray with rice, a bowl of soup, a small dish of spicy pickled cabbage, oysters in hot sauce, and some sort of spinach-like vegetable. There were big chunks of fish in the soup, and I found myself enjoying this meal as much as I had the previous night's feast. After supper I went for a walk in the moonlight up over a long hill and down to the harbor, where about twenty fishing boats surged restlessly against each other behind a small breakwater. The wind was bitter, out of the north, and I hurried back to my cubicle with its hot floor. Trying not to look at or think about the color and condition of the sheets, I spread out the bedding, lay down, and was quickly asleep.

Two days later I found Sŏkp'o. It was a long way off anything that resembled a beaten track, at the extreme northwestern tip of a jagged peninsula sticking far out into the Yellow Sea. For nearly two hours I had walked north from Mohang along a narrow path worn into steep, pine-covered slopes that fell away, on my left, to the ocean. Through the trees I could see the sparkle of the afternoon sun on the water, while the smell of warm pine needles was reassuringly familiar. A couple of miles out to sea a big, two-masted junk headed for dim islands on the horizon.

The trail climbed until it was a couple of hundred feet above the ocean and finally curved around the last shoulder of the mountain. There stretched out below me was one of the most beautiful places I had ever seen. Surrounded on all sides by water and connected to the mainland only by a narrow...