![]()

1

Aesthetics: Film as Art

Residents of Täby, a Stockholm suburb, were bewildered when Roy Andersson’s film team took over an old airplane hangar in their town in the summer of 1998 and, slowly but surely, built an entire train station in it—trains, platform, tracks, and all. Then they began hiring extras—more than a hundred of them—outfitted them in nondescript business clothes, and smeared their faces with white makeup. The locals were mystified, but they were happy to join in the production, bring everyone catered lunches, and provide any needed supplies. By the time shooting began, they very much wanted to know what the film was about—and they were astonished by the answer. It was about a man who gets his finger caught in a door.1

“I wonder why Roy Andersson built an the entire train station when he could just rent an old station,” said one of the extras, face smeared in paint and eating ice cream during a break in filming, in a Swedish television documentary on the making of Songs from the Second Floor. “That he builds the entire station for a single shot. Maybe he wants what is real to appear false, and what is false, to appear true. Maybe so!”2 The extras had many hours to ponder the meaning of it all. Since there are no edits within the scene, everything had to come together perfectly for the entire duration of the shot, which is more than five minutes long and includes a tracking shot—the only scene in the film where the camera moves—toward the end of the scene. It took ample rehearsals and more than a dozen takes to get the scene exactly right. Before the set was built, Andersson had sent members of his team to Prague to survey and photograph the city’s central train station, whose features provided a working model for their set design in Täby. The process took two months, which is more than twice the average shooting time typically spent for an entire film in Sweden.3

The finished scene, which takes place fifty-one minutes into the film, begins, as real life moments always do, in medias res. We hear the echo of commuters’ feet approaching on the train platform, punctuated by howls of pain: “Aj aj aj!” The man, presumably a commuter, has slipped and fallen on his way off the train, and his left arm is bent awkwardly behind him, his finger caught in the closed train door. Some commuters gather and speculate about how this could have happened, while others cast mildly curious glances and keep walking. A train conductor kneels next to him and looks up at the window of the closed door, waiting for someone to open it from the inside. The scene, a single take that lasts more than five minutes, is intended to represent the most banal of everyday life moments, and its dramaturgy is intentionally spare and precise, framing the man’s misfortune within the social space of the train station. There are no close-ups of the man’s facial expression; rather, cinematographer István Borbás places him in the foreground of a long, wide shot that reaches all the way back and up to the arched rear windows of the cavernous station. The man’s body is strewn awkwardly across the platform in the lower left corner of the frame, while the other human figures stand around him or walk briskly past to the right, except for the train conductor who kneels stiffly beside him. Most of the commuters, including the man, are dressed in muted gray, black, or gray-blue suits, forming an impression of modern humanity in the mass in its daily commute. The dialogue is sparse and banal, choreographed so that the discussion carries on across the man’s sprawled body. As they speak, the commuters address one another, largely ignoring the prone man moaning loudly at their feet:

Commuter 1: [standing behind the man to the right] What has happened?

Commuter 2: [standing in the left foreground] That’s a good question.

Commuter 3: [standing farther to the right] He’s stuck. He’s stuck in the door.

Commuter 1: Well, yes, we can see that, obviously. But how did it happen?

Commuter 2: He slipped, of course.

Commuter 4: [in the foreground to the right] Slipped?

Commuter 2: Yeah.

Commuter 4: How clumsy can you be?

Commuter 5: [an older woman with bright red hair standing next to Commuter 4] Don’t say that. It could happen to the best of us.

Commuter 3: He must have slipped backwards and hit his arm against the door, and it closed on him.

Commuter 1: Yes, but it’s clumsy all the same.

Man: Ahhhhhh! (see figure 1.1)

The banal dialogue is inspired by one of Andersson’s literary heroes, Irish avant-garde author Samuel Beckett, whose absurdist play Waiting for Godot (1949) famously consists entirely of two men doing and saying apparently nothing next to a dead tree on a roadside over the course of two acts. Andersson says that the reason he casts amateur actors is that they can deliver these ludicrously simple lines of dialogue “in an extremely truthful way, so that it sounds so ridiculously trivial coming out of their mouths, and at the same time it becomes very comprehensible, universal” (Andersson and Harringer 2000). The two commuters who seem to empathize with the fallen man—the woman mentioned above, and a portly man in a bright blue suit who helps the man up, hands him his briefcase, and dusts him off—are distinguished visually from the others through color (her bright red hair, his suit in a bolder shade of blue with a bright burgundy tie set against it). Andersson explained the rationale behind his meticulous dramaturgy in a 1998 interview with Film & TV: “I want the viewer to come to her own conclusions, I don’t want to point them out. I point things out in another way, by working very classically with diagonals, colors, and the film’s balance” (Weman 1998, 27). The characters in the scene are archetypes, and the entire scene is an abstraction, a representation of an ordinary moment that could, as the red-haired woman says, happen to anyone. For Andersson, the most significant moments of everyday life are the trivial ones—such as catching one’s finger in a door. The red-haired commuter in this scene underscores this by pointing to a scar on her own finger, which she explains got caught in a dresser drawer ten years earlier. Metaphorically speaking, this scene testifies that life’s most quotidian moments are the ones that shape and define us as human beings. The fact that Andersson built an entire train station to capture this trivial moment on film testifies to its significance.

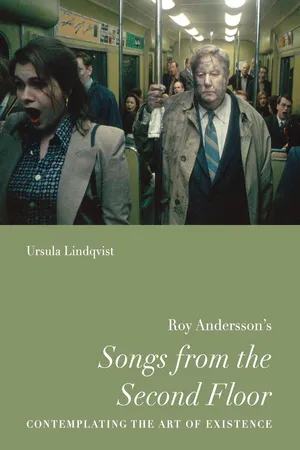

1.1“Caught a Finger.” Shot in an old airplane hangar in Täby, a city fifteen kilometers north of Stockholm, in summer 1998. For this single scene, Studio 24 built the entire set to make the hangar look like a train station, including the train, tracks, and platform. Photo courtesy of Studio 24; used with permission.

Andersson calls his distinctive form of filmmaking “trivialism,” a moniker that started as a joke between him and his crew.4 As they began filming Songs, Andersson realized just how apt a term it was, and he took to using it in press interviews, as well as in the director’s commentary of the DVD released in the North American market. Trivialism, according to Andersson, is motivated by the belief that the most important social and existential questions of our age come into focus in the most trivial, banal, and even absurd moments of everyday life. He explains:

One describes the world and our existence in their little trivial elements, and in that way I hope that one also can get to the big, enticing, philosophical questions. But how life is, life is of course trivial, we must button buttons, we must zip up zippers, and we must eat breakfast. It is exceedingly concrete and trivial, the whole of our existence. Even for those who are in positions of power. I like this very much, emphasizing this triviality, because it pushes people down to earth to that place where one actually belongs. (Andersson 2004)

Andersson’s definition of trivialism, then, affirms the fundamental equality of all beings in a world brutally divided into hierarchies. He views this style as a natural successor to the poetic realism of New Wave Czech director Miloš Forman and the neorealism of Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski (especially The Decalogue series, 1989), and he has also expressed admiration for the abstraction in Italian film auteur Federico Fellini’s films. Filmmaker Lana Wachowski has furthermore compared Andersson to a figure in the Western literary canon known for his sympathetic depictions of society’s “little people”:

I instantly felt an association with [Russian author Anton] Chekov and the way that Chekov understands the more dark, more selfish, narcissistic, destructive nature of humanity and yet he never stops loving humanity. And Roy Andersson has the same compassion, the same ability to dissect us and see us for all of our faults and yet is still able to embrace us and find humor and joy in the human condition. (Weintraub 2012)

In artistic terms, Andersson’s embrace of an “ism” to define his style, his polemical writings railing against conventional filmmaking, and his films’ rejection of the core conventions of his medium all evoke the avant-garde, which Susan Hayward has defined as film that “seeks to break with tradition and is intentionally politicized in its attempts to do so” (2006, 38). Most would agree that this is an apt description of Songs from the Second Floor, which not only presents scathing critiques of Western capitalist society in general and Swedish welfare society in particular, but also abandons the narrative structures that had defined feature filmmaking for more than a century.

In a radical departure from mainstream—or what Andersson likes to call “bourgeois”—cinema, the film refuses to anchor its plot in a major dilemma or conflict that the main protagonist must grapple with to develop as a character. In fact, plot, protagonist, and antagonist are all largely missing from the film. Rather, in each scene, Andersson seeks to capture the essence of some human experience—much as a painting or a lyrical poem does—but with a moving image. Collectively, the scenes provide a visual survey of the state of mankind. In an unsuccessful funding application to the Swedish Film Institute in 1994, Andersson described the film’s structure thus:

Narratively speaking, Songs from the Second Floor breaks with the conventions that have developed within the Anglo-Saxon film epic with their roots in nineteenth century melodrama. It doesn’t have a so-called “straight” story with the development of a conflict, plot twists, and resolution, according to set patterns. In Songs from the Second Floor, we meet an existence that can neither be apprehended nor surveyed, teeming with human destinies, some of which we come to learn a little more about, and they become the film’s main characters. But we will have the experience, not of following these characters, but rather of bumping into them, losing them from sight for a while, then bumping into them again—and again, and again.5

Songs from the Second Floor consists of no fewer than forty-six such images featuring an extensive cast of ordinary characters, most of them caught in painful—often painfully comic—moments. Together, Andersson says, they comprise an archetypal human being who is the film’s subject. “All of these people represent something that the human being has,” Andersson said in an interview. “Many people are needed in order to show how broad the human spectrum is. It isn’t enough with just one person.”6 Just as humanity is a perpetually flawed work in progress, in Andersson’s view, so the archetypal human being of his films never overcomes obstacles, achieves wisdom, or comes to a happy ending. As Andersson points out, life inevitably ends in death: “There will be no ‘happy end’ for any of us.”7

Andersson’s assertion that his films’ protagonist is a human archetype is what motivates his use of whiteface, a visual effect intended to equalize all of the characters. However, Swedish film scholar Hynek Pallas, whose 2012 doctoral dissertation Vithet i svensk spelfilm 1989–2010 (Whiteness in Swedish fiction film, 1989–2010) includes Songs from the Second Floor among the films discussed, has argued that whiteness in film is often conflated with a failed masculinity. “The man who experiences a loss of position and sees himself threated by women is a common trend in society,” Pallas said in a 2012 interview with Fria Tidningen in Stockholm. “This feeling of nostalgia and loss—not least for the utopian Swedish welfare society—is represented in films as well, as in Darling [directed by Johan Kling, 2007] and Roy Andersson’s films” (Borg 2012). Indeed, Andersson has acknowledged that he has been criticized for the film’s relative lack of meaningful female roles.8 As Swedish critic Kristina Lundblad wrote in a review in Göteborgs-Posten:

The Anderssonian human species is uniquely male. One hundred percent of the scenes are about men, men of different kinds. The women featured are divided into two groups—they are dead or wearing negligé. The former don’t say much, and the latter lie in bed and 1) wonder why the man comes home so late; 2) asks why he hasn’t called; 3) doesn’t want him to leave; or 4) carries on having sex while the good-guy ex-boyfriend she threw out stands on the street outside. (Lundblad 2000)

Two female characters who don’t fit these categories are the gyspy woman in the boardroom and the psychologist, both of whom serve as intermediaries for a higher power. Andersson has countered such criticism by saying that the film targets classes of people who wield social and economic power, and at the turn of the millennium, men still dominated these categories in Sweden and the rest of the world. Sweden is known for its policies promoting gender equality, and the country has consistently ranked very high in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (it was fourth in the world in 2014, the latest year for which rankings were available). Women’s access to the labor market, family-friendly policies, and a near-equal ratio of elected female and male leaders in Parliament have largely accounted for the favorable rankings.9 In addition, in May 2015, Swedish Film Institute CEO Anna Serner announced at the Cannes International Film Festival that SFI’s pathbreaking initiatives to achieve gender parity among films receiving SFI funding—which constitute the vast majority of Swedish films—had succeeded in less than three years’ time. In 2011, the year Serner took the helm, only 26 percent of all state film funding went to female filmmakers; by 2014, half of all funded films were directed by women, 55 percent were scripted by women, and 65 percent were produced by women (Byrnes 2015). (All three films in Andersson’s trilogy fall into the last category as their credited producers, Lisa Alwert and Pernilla Sandström, are women.) Despite the success of such initiatives, however, women are on the whole still paid less than men in Sweden for comparable work, and men continue to dominate business and industry elites (see, for example, Sanandaji 2014). Songs is a dystopic film, and Andersson believes that the fact that the sidelined women are not the ones calling the shots, but rather the ones asking questions and expressing bewilderment, casts them as a faint, collective voice of reason and sanity in the world of the film.

Pain, Not Pathos

Counter to Bordwell’s and Bergman’s readings of his films, Andersson says his aim is never to debase or ridicule the down-and-out characters who populate them. He claims that such critiques are rather indicative of the bourgeois sensibilities that have determined what filmic subjects are acceptable since the birth of the film medium. Andersson’s films cast a spotlight on banal, painfully real human moments that those who enjoy certain socioeconomic privileges are often buffered from. “The trivial is embarrassing for the cultural establishment,” Andersson said in an interview, noting that most filmmakers and critics tend to come from the middle class and are unaccustomed to confronting these kinds of moments so openly—and particularly not in a feature film. “Trivialism—I love it simply because it irritates the middle class,” he said, chuckling.10 At the same time, Andersson believes that elevating trivial moments to the level of high art not only treats them ...