![]()

Part One

ENTERING SENSITIVE SPACE

![]()

INTRODUCTION

The Fragments and Their Nation(s)

LET ME TAKE YOU ON A JOURNEY INTO “SENSITIVE” SPACE. Dahagram is a piece of Bangladesh situated in and completely surrounded by India. It lies, precariously perched, on the Indian side of the border, a mere 178 meters from the Bangladeshi mainland. Until recently, it was one of many such spaces scattered along the northern part of the India-Bangladesh border. Its boundaries are understood and agreed upon by both states. It even, occasionally, appears on maps. Yet such concrete cartographic representation belies the confusion and ambiguity of official attitudes toward and life within Dahagram. It is an “enclave”: a sovereign piece of one nation-state completely territorially bounded by another.1 The Bengali word for this phenomenon is chhitmahal. This word is often translated as “enclave,” but an equally suggestive translation is “fragment,” from chita, meaning detached or separate, and mahal, meaning self-contained building, portion of a building, or estate. Figured accordingly, the word “fragment” aptly describes Dahagram and its often-fraught relationships with its “home” and bounding state.

On May 11, 2015, the Indian Parliament ratified the 119th Amendment to the Constitution of India, passing the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement (LBA) between the two states. This amendment cleared the way for 111 similar Indian enclaves surrounded by Bangladesh and 51 Bangladeshi enclaves in India to be absorbed into their bounding states.2 On July 31, 2015, this exchange was implemented, and these enclaves, with the exception of Dahagram, ceased to exist in a formal cartographic sense. The implementation of the LBA ends, more or less, a long and fraught chapter in the political history of the border. The exchange cleared the way for enclave residents to freely and legally access services in their bounding states. At the same time, however, this political solution to a fraught territorial problem is not an end to enclave history. The ghosts and political imaginations that have long haunted these areas are unlikely to be so easily swept away, and the long and contentious histories that shaped these spaces will likely continue to influence life in and around them for some time to come.

The peculiarities of the enclaves date to the precolonial period. These spaces caused a range of administrative headaches during British colonial rule of the Indian subcontinent when they fell on either side of an administrative boundary—a jurisdictional division between a directly administered and a princely state. But it is primarily since the end of British rule and the Partition of India in 1947 that Dahagram and the other enclaves became problematic and anxious territories. At that moment, the new and hastily conceived Partition border was drawn among them—dividing greater Bengal into West Bengal in India and East Pakistan (later Bangladesh). This new boundary separated the enclaves from their home states. From that moment, the enclaves were formally “unadministered” because, though they were nominally sovereign pieces of their home state, the representatives of that state—such as police, military, and bureaucrats—could not legally cross the international border for the purpose of administering them.

Their ambiguous status as stranded pieces of territory—holes in the net of sovereign territorial rule—made these fragments the subject of acrimonious political and legal struggles in both states. They have been both persistent points of contention at this intermittently violent border and flashpoints for local and broader conflict over land, identity, and belonging. There have been repeated diplomatic agreements to resolve the enclave issue by simply absorbing them into their bounding states—until recently, to little avail. Indeed, the enduring existence of the enclaves despite such agreements has marked the challenging nature of postcolonial borders in South Asia.3 This book explores the enclaves, and Dahagram in particular, as a window into unsettled border politics. The challenges they pose cannot be reduced to questions of bureaucratic complexity or administrative failure alone. Throughout their history, Dahagram and the other enclaves have also been zones where postcolonial fears about national survival have been mapped onto territory, with profoundly human consequences.4

THE ARGUMENT

This book is an exploration of Dahagram. Throughout the chapters that follow, I engage Dahagram as a sensitive space. My use of the term “sensitive” to describe this space is not arbitrary. The term arose regularly during the course of my research. It was employed by state officials—always in English—as a means of explaining why information was unavailable, why particular things were or were not possible, and why these areas were markedly different or beyond the norm. “Sensitive” is a suggestive word. It means, variously, having perception or being perceivable; causing irritation, arousal, or intense emotion or feeling; being receptive to external influences; being involved with national security; and something likely to give offense if mishandled. It conjures feelings of urgency, pain, and danger without defining them. Evoked in political contexts, it summons concerns over security without specifying the nature of the threats. All of these meanings seemed variously at play when government officials used the word to describe the enclaves in offices in Dhaka, in the archives, in regional and local government offices, and at the border itself. Understanding these meanings is crucial. But in my own reappropriation of the term, I also have a larger project.

What does the term “sensitive” mean when applied to land or territory and to people living on or in it? In answering this question, I suggest that sensitive space can be an analytic for understanding the production of national territory in South Asia and beyond. In other words, sensitive space is a lens through which to examine the anxieties, uncertainties, and ambiguities that undergird territorial rule. Thinking with and through sensitive space, crucially, helps to link border management, projects of asserting jurisdiction over and control of space, and nationalist imaginations of territory as “blood and soil.” Moreover, it shows the fragility and instability at the heart of national territory.

The argument, in brief, is that the enclaves, and Dahagram in particular, trouble Indian and Bangladeshi nationalist imaginations of contiguous territory, of the border as neatly dividing inside from outside, and of identity and belonging. They unsettle the notion, particularly prevalent in postcolonial state formation in South Asia, that nationality and territory must align. At the same time, these spaces have repeatedly been appropriated as symbols of territory and belonging in broad debates over the survival of nation and state. The enclaves have, thus, been amplified in ways that have transformed them from administrative puzzles into challenging issues and into markers of postcolonial territorial anxieties—in other words, into sensitive spaces. The anxieties and uncertainties that condition nationalist responses to Dahagram are sedimented in its very landscape—through monuments, development initiatives, security measures, and more. Yet Dahagram is more than just a reflection of nationalist imaginations of space or the communal politics of territory. These imaginations—and the projects they portend—are reworked by its residents, who shape their own visions of belonging to community, nation, and state and who navigate projects of territorial rule for their own ends, but not under conditions of their own choosing.5

Understanding the production of territory is an urgent and critical project in South Asia and beyond. Such productions—especially at South Asian borders—remain fundamentally violent affairs. The India-Bangladesh border is a space in which the unfinished business of the Partition of India continues to be worked out. Partition, as countless studies have argued, imperfectly mapped communal identity onto territory, purveying a violent fiction that space could be administratively and nationally designated as “Hindu” or “Muslim.” Ongoing attempts to make this fiction a reality continue to yield disturbingly high body counts. The enclaves, and Dahagram in particular, are crucial to understanding the projects and puzzles of national territory, precisely because they are sites where the contradictions of such projects accumulate and are rendered visible.

ENTER THE FRAGMENTS

The enclaves’ fates have been regularly debated by people who have never visited them: politicians and bureaucrats who apprehend them primarily through cartographic representations and vivid territorial imaginations. These discussions have framed much of the enclaves’ history and certainly shape realities within them. Yet, to understand life in these sensitive spaces, it is necessary to view them from the ground.

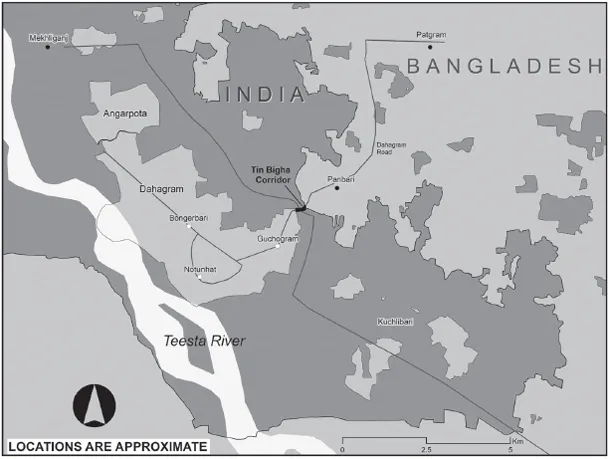

To that end, let us travel to the Bangladeshi enclave of Dahagram. At 18.6 square kilometers in size, it is the largest and, historically, most fraught of these enclaves. Dahagram is located at the remote northern tip of Lalmonirhat District in Bangladesh and is situated just across the border in Cooch Behar District in the Indian state of West Bengal. You cannot legally get to Dahagram from India. Instead, you take a long and winding bicycle-rickshaw journey from Patgram—the closest market town in mainland Bangladesh, roughly eleven kilometers away. The journey from Patgram to the border takes roughly ninety minutes, depending on the driver, his vehicle’s state of repair, and the weight of the load. Leaving Patgram’s bustle, you travel through a patchwork landscape of rice, maize, tobacco, and vegetables, passing only an occasional hamlet or tea stall. From the elevated roadway—built on a dike running above the fields—you can see for miles across a flat and strikingly beautiful landscape.

As you ride, your driver might point out border markers, seemingly placed at random, rising incongruously out of fields. These mark the borders of Indian enclaves—some the size of small villages, many little more than fields. Other than the oddities of border pillars, there is little else to show that you are traveling along an archipelago of enclaves. Even before their exchange, there were no fences, border guards, or gates to mark these spaces as distinct and sovereign parts of India. The barbed-wire border fence, which looms in the hazy distance, is the only reminder that you are traveling in a contentious, and intermittently violent, border region.

FIGURE I.1. Border post demarcating an Indian enclave along Dahagram Road, Patgram, Upazilla, Bangladesh, 2007. Photo: Jason Cons

Coming into Panbari, the last small village before the border, you encounter a Bangladesh Rifles (BDR) camp and troop post.6 Even here, the setting remains fairly peaceful, as off-duty soldiers lounge together in lungis, the cloth skirts worn by many when out of uniform, doing laundry, playing games of karom. But as you round the last bend leading to the Tin Bigha Corridor, a tensely regulated landscape emerges. On the left is a BDR checkpoint, always occupied by two or three armed soldiers. Immediately following this, you pass through the gates of the Tin Bigha Corridor, a 170-meter-long land bridge to Dahagram running through Indian territory and maintained by India’s Border Security Forces (BSF). This Corridor was initially proposed in the now infamous 1974 LBA between India and newly independent Bangladesh, which also made provision for exchanging the remaining enclaves. The proposal to open the Corridor became the focus of a fraught and occasionally violent struggle in both India and Bangladesh. It did not open for another seventeen years, and then only partially. This Corridor, the only one of its kind among the enclaves, connects Dahagram to “mainland” Bangladesh, albeit precariously.

MAP I.2. Dahagram. Map by Amanda Clarke Henley

As you enter the Corridor, on the immediate right is the first BSF post, where a senior officer and armed troops take scrupulous note of all who pass. You are now in Indian territory and under the BSF’s jurisdiction. Moving through the Corridor, whether you are a foreign researcher or a resident of the enclave, you feel the suspicious scrutiny: Who are you? What are you doing here? Where do you belong? Midway between the Corridor’s gates is a crossroads. Go left or right and you enter India. Go straight and you enter Dahagram (and in doing so, reenter Bangladesh). In the middle of the Corridor, a uniformed member of the West Bengal Traffic Police stands not far from a monument to two Indian activists, killed when the BSF fired into a crowd protesting plans to open the Corridor in 1988. He guards the intersection, club (lathi) in hand, ensuring that no passersby veer from one country into the other. Beyond the intersection, you pass yet another BSF station on the left, also staffed with armed troops and note-taking officers. This station has a counterpoint BDR post on the right as soon as you pass over the border into Dahagram and back into Bangladesh. It is also staffed with armed guards, also taking scrupulous note of who and what enter and leave the enclave.

Surveillance, regulation, and instability are part of the fabric of daily life for Dahagram’s approximately twenty thousand residents.7 So too is ambiguity, confusion, and uncertainty. Information about the enclave is difficult—occasionally impossible—to access. Dahagram, as a space, is characterized by confused forms of power, exploitation, and oppression. The Tin Bigha Corridor that connects Dahagram to Bangladesh is not an “official” border crossing. Though all traffic going into and out of the enclave passes through sovereign Indian territory, passports are not necessary for this movement. Unlike the other enclaves scattered along the border, Dahagram is administratively, as well as territorially, part of Bangladesh. It has a formally elected government, or Union Parishad. It has a family planning unit. Microcredit organizations and other small-scale nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) offer services there. Theoretically, the national government imposes taxes, registers land, and distributes aid. In short, it possesses many features common to other villages and towns in Bangladesh. Yet it is unmistakably a zone apart. Inside the Corridor, the BSF has authority to implement random inspections, to create seemingly arbitrary conditions for passage, and to scrutinize and, as many enclave residents have it, intimidate those passing through. The Tin Bigha Corridor is a militarized space, held and protected by an armed paramilitary force that only grudgingly allows enclave residents to pass. The Corridor clearly belongs to India. And Dahagram is unquestionably not a “normal” part of Bangladesh.

Dahagram, in part because of the long history of struggle over the Tin Bigha Corridor, also differs from other enclaves, where borders are permeable, marked only by concrete pillars that are often hidden in fields. In contrast, the borders of Dahagram are regularly patrolled by both the BSF and the BDR.8 Panoptic Indian watchtowers surround the enclave. Ingress and egress for residents of Dahagram are difficult, dangerous...