eBook - ePub

In the Circle of White Stones

Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet

Gillian G. Tan, Stevan Harrell

This is a test

Share book

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

In the Circle of White Stones

Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet

Gillian G. Tan, Stevan Harrell

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This narrative of subsistence on the Tibetan plateau describes the life-worlds of people in a region traditionally known as Kham who move with their yaks from pasture to pasture, depending on the milk production of their herd for sustenance. Gillian Tan's story, based on her own experience of living through seasonal cycles with the people of Dora Karmo between 2006 and 2013, examines the community's powerful relationship with a Buddhist lama and their interactions with external agents of change. In showing how they perceive their environment and dwell in their world, Tan conveys a spare beauty that honors the stillness and rhythms of nomadic life.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is In the Circle of White Stones an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access In the Circle of White Stones by Gillian G. Tan, Stevan Harrell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Kultur- & Sozialanthropologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

Kultur- & SozialanthropologieCHAPTER 1

Getting to Dora Karmo

I arrived in Dora Karmo in the early morning light in the back of a small tin-can car that shook and rattled on the bumpy dirt road. The late winter cold had caused the grasslands to turn brown. This color contrasted sharply with the jagged rocky edges of Zhara mountain and the stark blue sky. The familiar sight of the mountain eased my nervous anticipation of what lay ahead. Would I be physically able in that environment? Would I be psychologically strong enough to withstand this fieldwork? The realization that Lhagang (Ch. Tagong) town, where I was coming from, was less than twenty-five kilometers away provided some reassurance. Lhagang was a place I had been arriving at, and leaving from, for the past five years. I had good friends there.

Lhagang in 2006 was still a “Wild West” sort of town, even though it was the administrative and social hub for eighteen administrative villages of nomadic pastoralists in the surrounding grasslands. Lhagang was also an administrative township in a county called Kangding, the prefectural seat of Ganzi, which was created in 1955 as an administrative Tibetan prefecture under the Chinese Communist Party. During the earlier Republican period (1911–49), the area of Ganzi was coterminous with eastern Xikang, and formed part of the historical Tibetan region of Kham (also known as Chubzhi Gangdrug, or Four Rivers, Six Ranges). Ganzi covers an area roughly the size of Nepal (150,000 sq km) and the almost one million people who live here are mostly Khampa Tibetans, known for being the most warrior-like of all Tibetans. Male Khampa nomads still strutted down Lhagang’s single dusty street with long knives attached to their left hips and right thumbs hooked to the belts holding up their heavy chubas, or long Tibetan robes. A traveler would need to pass through Lhagang if using the northern branch of the Sichuan–Tibet highway, a winding and adventuresome road that looped almost four thousand kilometers between Chengdu and Lhasa.

Lhagang is home to a large Tibetan Buddhist monastery of the Sakya sect. The monastery sits cradled in a crescent created by three small hills: Chenrezig in the middle, Jambayang to the left, and Chana Dorje to the right. For local people, the hills are emanations of three major religious figures in Tibetan Buddhism: Phagpa Chenrezig (Avalokhiteshvara) representing Compassion, Jambayang (Manjushri) representing Wisdom, and Chana Dorje (Vajrapani) representing Power. In addition to its contemporary political, economic, and social significance for its townspeople, Lhagang holds particular religious, historical, and cultural significance for this region of the Tibetan plateau. The topography connects it deeply to narratives of Tibetan sacred geography, and the Jowo religious statue in its monastery links it strongly to the religious center of Lhasa, 1,700 kilometers west.

Lhagang was significant for me in several ways. The head lama of its Sakya monastery is Zenkar Rinpoche, who now lives in New York and gave me my Tibetan name in 2000 while I was working for Trace Foundation, a New York–based organization that had supported his study at Columbia University. Working with this foundation also introduced me to Dorje Tashi, the influential local incarnate lama from Dora Karmo who had established several key schools and cultural institutions in the Lhagang area. My evolving relationship with Dorje Tashi, who was first an acquaintance, then my student in English-language learning, then adviser on my research, and, finally, a friend, is detailed in chapter 5.

I traveled here frequently while I was an English-language teacher at the Kangding Vocational College in Gudrah town, about thirty-seven kilometers south of Dartsedo. When I arrived to teach English in 2000, Gudrah was a dusty one-street town with a handful of noodle restaurants and small shops selling sundry items. In my year there, the town’s streetscape was transformed from old wooden houses to concrete buildings that were already dirty and gray from the process of construction. The vocational college had just built a new guesthouse, and the government had just finished constructing the Erlangshan tunnel. I was not aware of this at the time, but the flurry of construction was supported by the inflow of money to Sichuan as a result of the Develop the West (Ch. Xibu Dakaifa) campaign. As I was the first resident foreigner in the prefecture, the administrators and teachers at the vocational college, all Han, who were solely responsible for me, were acutely worried about me. In those initial months, as soon as I stepped out of my room in the guesthouse, an administrator or teacher would appear to take me to meals, classes, and trips to town. These appearances were usually accompanied by the remark “We are worried about your safety.” When the administrators and teachers eventually tired of the responsibility, students took over. This constant tracking was immensely tedious and greatly influenced my first impressions of rural China. Lhagang was a place that I had gone to regularly in order to escape from the claustrophobic valley of Gudrah town.

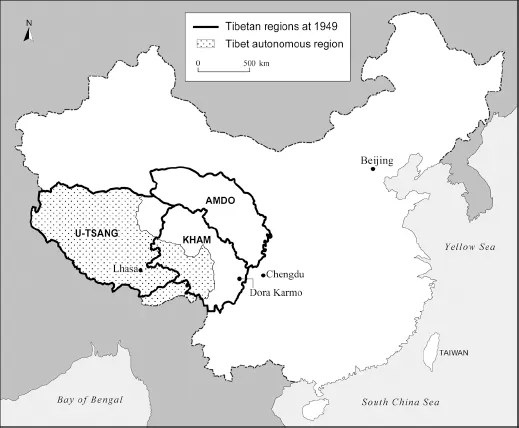

MAP 1

Tibet Autonomous Region (shaded) overlaid with estimated boundaries of Tibetan regions in 1949. Cartographer: Chandra Jayasuriya

Tibet Autonomous Region (shaded) overlaid with estimated boundaries of Tibetan regions in 1949. Cartographer: Chandra Jayasuriya

MAP 2

Sichuan, with detail of Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Cartographer: Chandra Jayasuriya

Sichuan, with detail of Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Cartographer: Chandra Jayasuriya

In those early years, I made good friends in Lhagang, one of whom was a student at the Kangding Vocational College when I taught there. This friend, Tashi*, had studied English with me and diligently applied himself. He eventually enrolled in a well-regarded English-language training program for Tibetans. After receiving this training, he would return to Dartsedo County to teach English to Tibetan students at a local middle school, which in the Chinese educational system incorporated grades six through nine.

In 2006, I was staying in Tashi’s family home in Lhagang and trying to think about the best way of organizing my stay in Dora Karmo. The person who would eventually help organize my stay in Dora Karmo was Tashi’s cousin, a young man who had studied English in India and recently returned to Lhagang. He walked into the large, elaborately painted and decorated room where family members drank tea, ate meals, and watched television. Guests such as myself were hosted in this room. He looked at me, faintly surprised at finding an unexpected person in the room, before turning to his maternal aunt, Tashi’s mother.

“She is Tashi’s teacher,” Ala Lhamo* said in her quiet manner. Then, slightly under her breath, she added, “She is a foreigner.”

He turned to look at me and said, “Hello,” in English.

“Hello,” I replied in English. And then switching to Tibetan, I explained, “My name is Nyima Yangtso. I’m from Australia—well, I come from Malaysia, but I live in Australia now.”

“Oh, do you speak Tibetan?” he asked, with surprise again in his eyes.

“Yes, a little,” I replied. “I learned with teachers at the Sichuan Province Tibetan School.” The school, located in Dartsedo town, is a middle-level vocational school (Ch. zhongzhuan) incorporating grades nine through twelve, and was distinctive because it provided a traditional Tibetan curriculum to local young Tibetans. This curriculum, taught in Tibetan language, included Tibetan medicine, Tibetan Buddhist philosophy, astrology, and painting thangka (traditional Tibetan cloth painting). The school had begun in 1981 in a tent in Dzogchen town. Significantly for me, Zenkar Rinpoche had played a key role in establishing the school and securing its present location in former army barracks outside Dartsedo.

“Oh, you speak our dialect well,” Tashi’s cousin remarked.

After some further small talk, it emerged that he had been a primary-school teacher in Dora Karmo for two years after his return from India. I was immediately attentive because this was an opportunity to enter Dora Karmo that was not associated with either Dorje Tashi or the development organization working in the area. Earlier that day, I had met a local acquaintance who knew some nomads from Dora Karmo. But she had been incredulous that I wanted to live with the nomads and mixed her assurances that she would help me with liberal doses of worry and doubt: life is very hard, there are no vegetables, they are dirty, it is cold, you are by yourself . . . the list went on. I doubted she would try her best. Meeting Tashi’s cousin, then, signified a favorable alignment of the stars.

“Do you know a family in Dora Karmo that I can stay with for a few months?”

He looked at me and asked, “Why?”

I replied, “To learn more about Tibetan nomad culture and to learn nomad dialect. You see, I speak like a farmer because all my teachers are farmers!”

He laughed, and I continued, “I am a student now at my university in Australia. I want to learn about the nomad way of life. I want to live with a family and eat what they eat, work with them. I also want to understand what they think about the changes happening here.” I gestured around me to indicate the larger Lhagang area. “For example, what do they think about this American development organization and its work?”

He listened to me carefully. While I was talking, the telephone rang. After I stopped talking, Ala Lhamo called to him and said, “Tashi wants to speak with you.” Tashi had called at an opportune time. Through his cousin’s replies, I gathered that my friend was instructing him to help me as best he could. When our conversation resumed, my conclusions were confirmed.

He said, “You can stay with the village teacher, I think. He is an older man with two daughters, maybe the same age as you. I will arrange it for you, don’t worry.” He paused and then added, “He is a good man.”

I was grateful to him for helping me. The next day in Lhagang, I prepared for my initial stay of ten days in Dora Karmo, which would allow me to assess the situation for a much longer stay of six months. Even as I became familiar again with the town, I noted more changes in both the streetscape and the lifestyle. It made me recall past conversations in Dartsedo with teachers from the Sichuan Province Tibetan School who were also my teachers both in the Kham dialect of Tibetan language and in contemporary issues of Tibetan culture and society. From them, I learned innumerable facts about the present situation of Tibetans living in Ganzi, but I also learned about their childhoods in nomadic and farming areas of Kham in the late 1960s and early 1970s, about the Sichuan Province Tibetan School in its early years, first in Dzogchen town and then in Ta’u town, and about their concerns regarding the gradual erosion of Tibetan language and traditional Tibetan culture in Ganzi.

One conversation at one of my many lunches with these teachers, usually at a nearby Han restaurant, stood out.

“The problem now is that the culture holders are not the decision makers,” said Teacher Palzang*.

He continued, “Of course culture is never permanent and fixed. Tibetan culture has been influenced by external forces for most of its history. But we have always had the choice to accept the beneficial things and to reject unnecessary aspects. Now change is happening so quickly that our culture is approached from all sides. The people who are making change are not the culture holders. And I think the most important thing we can do is to allow people to think and choose among the new things that are coming into Tibetan society.”

Teacher Dorje* had been listening intently and nodded his head in agreement. “Ya ya, but how do they think and choose? That is also important. Before, maybe they didn’t have to think and choose so much because there were not so many new things. But now, they have to choose all the time, yet they are not strong enough in their own ways, their own language, and their own culture. For example, thangka paintings. We have teachers here who are very good thangka painters. They were trained in the traditional way, and they have a good foundation in traditional methods. Now, if they were to change some small part of their paintings, to develop a new modern style of thangka, then I think it is OK. They have good knowledge about the traditional way. But now, more and more, we see thangka painters who do not have good knowledge but who paint modern thangka. Is their work good? I don’t think so!”

“Eh, Yangtso, what he means is that everyone must come to our school to learn thangka painting!” Teacher Nyima* jokingly added.

“Yes, Teachers Sonam* and Tsering* [who teach thangka painting] will be very rich then!” Teacher Dorje laughingly added. There was laughter around the table as the conversation continued.

“This is a problem,” said Teacher Palzang. “We think about it every year, because every year, the level of Tibetan language for our students is worse and worse. There will be a day when all we do is teach ka kha ga nga,” he added ruefully, referring to the first four letters of the Tibetan alphabet.

Then in a matter-of-fact way, he added, “This school was started by great Tibetan scholars, such as Thubten Nyima [Zenkar Rinpoche]. It has produced great Tibetan scholars, like Tashi Tsering. Our students used to be taught by illustrious Tibetan scholars, including the Panchen Lama. And soon, it will teach ka kha ga nga.”

Teacher Dorje said, “The problem is also with society, and we ourselves, as teachers, must be very careful. More and more I think that the teachers here are less committed. They are part of the changes that are happening in society. Look at Dartsedo and also farther out in Rangaka and Lhagang. With all the new buildings and tea shops, it is hard for us to focus on teaching let alone for the students to focus on learning. There are so many distractions now. And when the level of students becomes lower and lower, it is harder to be a committed teacher.”

“You know, Yangtso,” Teacher Nyima said to me, “I have started to use some of the teaching techniques that you used when you taught me English. I think some of those techniques are really useful; they helped me a lot!”

“Oh, thank you so much! I am so happy to know this,” I said, delighted by this compliment.

I had followed their conversation in Tibetan with interest and only a little difficulty. Collectively, these were my Tibetan-language teachers. They were careful to use words that they knew I could understand, and they spoke clearly and slowly so that I would comprehend what they were saying. Nonetheless, my language skills at this time were developing quickly because, even though I had stopped working with Trace Foundation, I remained in Dartsedo for close to a year informally teaching at the school and informally learning Tibetan. It was mainly during this time, between 2003 and 2005, that I settled into a Tibetan way of life and began to feel very familiar with the mannerisms and habits of urban and intellectual Tibetans. I developed a sensibility toward Tibetan culture that, nevertheless, would be challenged when I started my formal fieldwork in Dora Karmo.

Two days after meeting Tashi’s cousin, I was on my way to Dora Karmo. The bumpy journey was longer than expected. The grasslands swept out the nearer we came to the mountain range of Zhara, which loomed in impressive proximity the higher the little car chugge...