![]()

Part 1

Making Blackness Serve

![]()

1

Containing Bodies—Enscandalizing Enslavement

Stasis and Movement at the Juncture of Slave-Ship Images and Texts

CARSTEN JUNKER

The Slave Trade came through the cramped doorway of the slave ship.

—Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation

Early transatlantic abolition has been credited as a social movement that created the emotional climate necessary for putting an end, or at least a legal stop, to the trade in enslaved Africans in the early nineteenth century. But abolition was not merely a social movement; it was also a set of visual and textual practices that “enscandalized” the transatlantic slave trade and slavery in the Americas—in other words, it sought to make audiences see the apparatus of enslavement as a scandal—by drawing on visual and textual depictions of Black bodies on slave ships. This essay considers early abolition in the transatlantic sphere as a framework within which eliciting emotive responses on the part of audiences—such as sympathetic fellow feeling or shame—featured as a central strategy, and it interrogates the specific means and effects of producing and anticipating feelings as they pertain to the depiction of Black bodies on slave ships. In the late eighteenth century, slavers came to be considered “a huge, complex, technologically sophisticated instrument of torture,” as slave-trade historian Marcus Rediker has suggested.1 How, then, did particular visual and narrative depictions of Black bodies on slave ships contribute to making slavers intelligible, and dreaded as such, to respective audiences? To consider this question, this contribution examines broadsides that feature depictions of slave ships as a paradigmatic site for the evocation and distribution of feelings in abolitionist discourse. It addresses the nexus between images, feelings, and texts, and suggests construing the relation between slave-ship images and texts as a hinge that worked toward mobilizing anti-slavery sentiments among white audiences around 1800.

My approach to abolition is shaped in contradistinction to an understanding of abolition that celebrates it as movement against the slave trade and an expression of Enlightenment humanitarianism and white moral self-aggrandizement. The 2007 celebrations of the bicentennial of abolition in Britain, for instance, can be seen as and have been criticized for affirming abolition as a British national project of which a broad public can be proud. One particular critique, from noted historian of the slave trade Marcus Wood, concerned endeavors of framing abolition as the struggle of a small number of white men.2 Framing abolition as a white project that granted the enslaved emancipation renders Black agents passive yet grateful recipients of freedom and devalues or makes invisible various forms of resistance on the part of the enslaved. An outstanding figure such as Olaudah Equiano, for example, is only one instance of early abolitionists of African origin who got actively involved in campaigning against the slave trade, and the shape and form his impact took is only one among many others.3 Resistance among the enslaved began even before they were forced onto the ship. Thus, while I argue in the following that the slave-ship images examined here take part in relegating the enslaved to a sphere of passive victims, it should be noted, following historian James Walvin, that transatlantic enslavement “is the story of enslaved resistance as much as slave-owning domination.”4 Against this backdrop, I turn attention to the ambivalent use of slave-ship broadsides in the campaigns of white abolitionists. Slave-ship broadsides had a decisive impact on the emergence of an abolitionist culture of feelings shaped predominantly by compassion. To assess this impact, I argue, it becomes necessary to examine how feelings among white audiences could be mobilized and directed in specific ways through the intricate linking of images and texts in slave-ship broadsides.

The Brooks

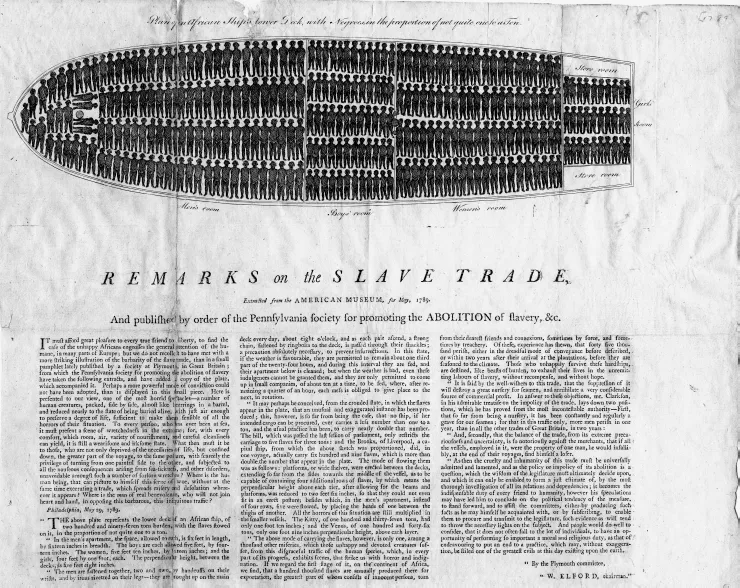

No slave ship image is better known or has shaped the historiography of the slave trade and abolition as well as its late eighteenth-century iconography more profoundly than the image of the slave ship Brooks.5 The ship was built in 1781 and named for the slave-trading merchant Joseph Brooks Jr., who had commissioned it and was its first owner. It made ten voyages until 1804.6 The famous abolitionist image of the Brooks was first printed in November 1788 by the Plymouth chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. This group had undertaken great efforts to collect data about the slave trade, and the depiction of the Brooks was the result of their effort. The image of the ship was supposed to provide evidence of the realities of the trade and would be redrawn and reprinted several times on both sides of the Atlantic. The broadsheet “Remarks on the Slave Trade” was published by the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery a year after the first publication of the Brooks image (figure 1.1). This broadsheet was roughly eleven by seventeen inches (twenty-seven by forty-two centimeters); Philadelphia printer Mathew Carey produced twenty-five hundred copies of this version alone.7

1.1.

Remarks on the Slave Trade (Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1789), engraving.

The distribution of the broadsheet with the image of the slave ship followed a well-scripted plan that was part of an intensive campaign, a central aim of which was “to make the slave ship real,” which was “accomplished in a variety of ways—in pamphlets, speeches, lectures, and poetry, for example.”8 In the text-image relation of the broadside, feelings came to play a significant role. As I contend, feelings mediated between image and text and worked toward mobilizing anti-slavery sentiments. In the struggle against the trade in human beings—which was a system based on rational principles, a regime made up of numbers, tables, and calculations for profit—emotions became an increasingly significant strategy of agitation. Abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic, in both Plymouth and Philadelphia, evoked feelings such as horror and shame among free white men and women and appealed to their compassion for the suffering of the enslaved. This mobilization of compassion drew on the assumption of a shared humanity between the free and the enslaved.

The Brooks broadside was deemed highly successful in provoking an emotional response on the part of a larger free public by evoking the violence and terror of the trade. One of the major British protagonists of the abolitionist movement at the time, Thomas Clarkson, corroborated the significance and success of the Brooks broadside in stirring up public sentiments against the trade. In the second volume of his History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, Clarkson writes the following about its putative shock-and-awe effects: “[The] famous print of the plan and section of a slave ship … was designed to give the spectator an idea of the sufferings of the Africans in the Middle Passage.… [It] seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it, and … was therefore very instrumental, in consequence of the wide circulation given it, in serving the cause of the injured Africans.”9 As Rediker also notes, the image of the Brooks “represented the miseries and enormity of the slave trade more fully and graphically than anything else the abolitionists would find. The result of their campaign was the broad dissemination of an image of the slave ship as a place of violence, cruelty, inhuman condition, and horrific death. They showed in gruesome, concrete detail that the slaver was itself a place of barbarity.”10

In a review of Rediker’s book, historian Eric Foner equally underlines the impact that the image of the Brooks had. Foner considers the “diagram of the vessel … the era’s most effective piece of visual propaganda.”11 Introducing the broadsheet with the image of the Brooks into public debate was what—with Michel Foucault—may be called a discursive “event” that was incorporated in and changed the course of abolitionist discourse.12 It provided specific conditions for white audiences to configure their feelings in certain ways, allowing for the possibility of mobilizing their sympathy for the enslaved. Like Clarkson before him, Rediker suggests that the campaigners assumed there was a supposedly inherent power in the image of the ship to evoke emotive responses on the part of white audiences—in essence, unmediated responses to the immense violence and terror to which the trade subjected the enslaved. In this vein, the stillness depicted in the slave-ship image has been read as an indexical sign for the violent subjection of Black bodies.13

While the violence inherent in the stillness of the image is a matter of fact, I question the assumption of an inherent power in the image. I argue that it is precisely this power that should be questioned, suggesting that we throw into doubt the assumption that this image necessarily provoked any affective responses on the part of white audiences in the late eighteenth century—were it not for the knowledge they had about its discursive context. I propose an alternative reading of the image that instead focuses on a different aspect of its visual organization: its static orderliness and the lack of chaos and movement that it projects. An audience in our own contemporary moment might be reminded of a barcode used to identify a product. What we see are black markers as signs for contained Black bodies. We see the containment of Black bodies and the containment of chaos, disease, uproar, and emotions. The image shows no affects among its African captives whatsoever, no signs of potential resistance on the part of the enslaved. It appears to naturalize the order of the enslaved aboard the ship. It renders them mute and de-emotionalizes them. By featuring the enslaved as a mass of moveable but static objects, the image contributes to their commodification. While thus, to reiterate, this stillness can conclusively be read as expressing the violence of the so-called Middle Passage, I also emphasize that one reason for the success of the image lay in its latent function of containing this violence—of counteracting the fear on the part of a broader public of the threat of potential acts of resistance among the enslaved aboard the ship. The diagram projected a sense of control over the possibilities of such active resistance of the unfree. With its abstract figures, the image of the ship is rendered tame by state-of-the-art domesticating craftsmanship and appropriation. In that respect, it is comparable to the objects depicted in the plates of eighteenth-century encyclopedism, famously discussed by semiotician Roland Barthes with reference to Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopedia. Barthes notes: “The Encyclopedic object is … subjugated (we might say that it is precisely pure object in the etymological sense of the term), for a very simple and constant reason: it is on each occasion signed by man; the image is the privileged means of this human presence, for it permits discreetly locating a permanent man on the object’s horizon … what is striking in the entire Encyclopedia (and especially in its images) is that it proposes a world without fear.”14

The visual depiction of objects in the Encyclopedia served the purpose of inventorying, cataloguing, and thus appropriating them into pre-given classificatory schemas. Similarly, the image of the Brooks suits a discursive framework of Enlightenment reason and rational orderliness. While this early version provides a view of the slave deck based on “thumb proportions,” the design of later images of the ship “obeys closely the technique for depicting a naval vessel set down in late-eighteenth-century naval architectural guides.”15 With Barthes, we can assume likewise that the depiction of the ship proposed a world without fear. As he notes further, practices of naming...