![]()

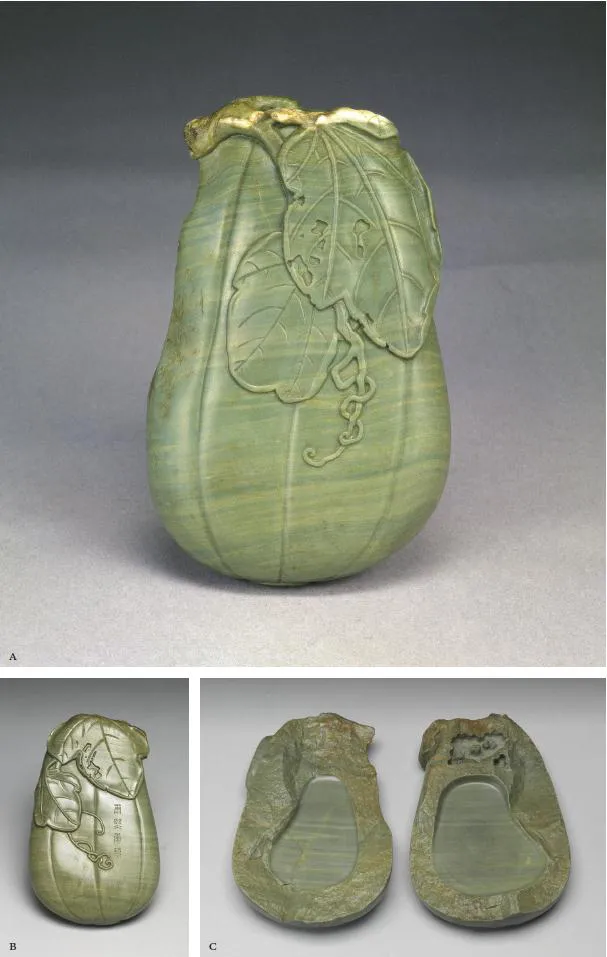

FIG. 1.1. Inkstone shaped as a gourd with ingenious cover: (A) cover; (B) back of inkstone; (C) open view, with cover on left and inkstone on right. The green Songhua stone is polished on the outside to resemble a gourd cut from the trellis. When the viewer lifts the cover, he finds the jagged edges of the inkstone (fitted perfectly to the cover) that look as though they were chiseled from the side of the hill as Kangxi had discovered them. The raw strength of the hard Songhua stone is conveyed by this ingenious design, which departs from the convention of an ink-slab encased in a box. L 14.6 cm, W 9 cm, H 2.4 cm. National Palace Museum, Taiwan.

1

The Palace Workshops

THE EMPEROR AND HIS SERVANTS

OCCUPYING A CLUSTER OF BUILDINGS TO THE WEST AND NORTH-west of the Hall of Supreme Harmony at the heart of the Forbidden City, the Workshops of the Imperial Household (Zaoban Huoji Chu, hereafter Imperial Workshops) were so saturated with motion and action that the literal meaning of the Chinese verb “to work” in them seems most apt: “to walk and run.”1 Founded by emperor Kangxi in 1680, the workshop system was responsible for the making, repair, and inventorying of all the objects large and small required for the upkeep of the imperial family and the ceremonial functions of the court. Cataloguing the tribute goods received by the court as well as manufacturing the myriad gifts the emperor conferred on favorite subjects and tributary states also came under its purview.

Specialized workshops organized by branches of knowledge appeared in 1693; by the time records began to be kept systematically in 1723 there were over twenty of these works (zuo), handling an array of materials and processes from enamel, scroll-mounting, lacquer, jade, and leather to firearms and mapmaking. The number eventually grew to over sixty.2 Inkstones were among the first objects made in the palace workshops. There appears to have been an inkstone works almost as soon as the formal establishment of the workshop system; in 1705 Kangxi appointed two designated superintendents and placed its jurisdiction under the Hall of Mental Cultivation, both suggesting increased workload. Although details are not known because of the paucity of recordkeeping before 1723, the Kangxi-era Inkstone Works was staffed by artisans from Jiangnan, in the south, who also carved ivory and jade, as was the customary practice in the subsequent reigns.3

It is perhaps not an accident that the heightened production of inkstones coincided with the Qing’s transition from military to civil rule in 1681 after Kangxi quelled the rebellion of the Three Feudatories, thus securing the future of the nascent dynasty. The emperor’s genius was to graft an unmistakable Manchu identity onto an instrument that signified Chinese literati culture by fashioning it out of a brand-new stone, later known as Songhua stone (after the Sungari river), quarried in the imperial homeland of present-day Liaoning, Jilin, and Heilongjiang, Manchuria. It is likely that the emperor made the “discovery” during his second pageantry there to report his triumph and make offerings to his ancestral tombs in 1682.4

The emperor recalled his delight in an essay: “On the slopes of Dishi Hill to the east of Shengjing [Shenyang], outcrops of rocks lie in abundance. The stone is strong and warm in substance, green and bright in color, and replete with brilliant patterned veins. When held in the hand it feels as though it is dripping with a lustrous tonic. Some people make knife or arrow sharpeners out of it. Upon inspection, I thought that it would make fine inkstones.” Kangxi’s use of such adjectives as warm and lustrous as well as the pun “patterned veins” (wenli, also the principle of textual composition) betrays his familiarity with the vocabulary of inkstone connoisseurship in the Chinese scholarly tradition, but his appreciation for a “strong” (jian) stone, which seldom appears in the literature, suggests that he had a mind and taste of his own (fig. 1.1). In any case, the emperor had craftsmen fabricate several inkstones in antique shapes for “testing.” To his delight, he found that they yielded better ink than the green Duan stone, and “even those famed stones from the old pits [of the Duan quarries in Zhaoqing, Guangdong] have nothing over them.” Kangxi had the new inkstones boxed in brocaded cases for display on his desk so that he could enjoy “intimacy with literature and ink everyday.”5

The account conveys Kangxi’s observant eyes, inquisitive mind, and predilection for experimentation. He also made no bones about the political utility of Songhua inkstones. In concluding his essay, Kangxi drew an analogy between the obscure stone, scattered in remote hillsides awaiting discovery, and the “concealed and dejected scholars” who “must be hiding in forested mountains or marshes in the realm. Repeatedly I have issued edicts to recruit them, enlisting their service from all directions, with the intention that no talent will be left unappreciated in the fields.”6

Written on the heels of the elimination of the last substantive threat to Qing legitimacy and security, Kangxi’s reiteration of his daily intimacy with “literature and ink” and appeal to hidden talent in the marshes bear an unmistakable air of a victor’s gesture of reconciliation. The transformation of knife and arrow sharpeners into grinding stones for ink epitomizes the shift in manner and style from military to civil rule. About a decade later, during Kangxi’s third pageantry to his ancestral homeland in 1698, he identified more stones suitable for inkstones while hunting and foraging, including a green stone from Mount Ula in present-day Jilin. He may have also arranged for more systematic exploitation of the quarries. A new material culture of the Qing court, with dedicated operations in sourcing and making, was born.

Not long after, in the early 1700s, Kangxi began to bestow gift inkstones made of Songhua stones to Chinese scholars in his inner circle. In his New Year audience of 1703, for example, he gave one Songhua inkstone to each of the sixty Hanlin academicians assembled in his Southern Study in the inner palace. The appointment of two supervisors overseeing inkstone making and the relocation of the Inkstone Works to the Hall of Mental Cultivation in 1705 were likely measures instituted to meet the new and growing demand for gift inkstones.7 Along with books and calligraphy in the imperial hand, gifts of inkstones sent an unmistakable message to their recipients, Chinese scholars all: I am one of you. Although motivated by political savvy, Kangxi’s respect for Han literati culture was by all accounts heartfelt. This respect, however, should not detract from the fact that in its management and attitude toward material processes, the Qing empire represents a significant departure from its predecessor in principle and in practice.

A NEW TECHNOCRATIC CULTURE

The imperial workshop system is emblematic of a new Qing ruling style that can only be called materialist. The palace workshop was but the tip of an iceberg, a conglomerate of manufactories that also included the giant porcelain works in Jingdezhen and silk manufactories in the heartland cities of Nanjing, Suzhou, and Hangzhou, comprising the largest textile enterprise in the empire. The “material empire,” of which the workshop system was a part, operated under the auspices of the Imperial Household Department (Neiwufu; literally, Bureau of Inner Affairs), a vast politico-cum-economic institution. Tasked with managing the finances and economic resources of the royal house, it was the emperor’s “personal bureaucracy,” staffed by his bondservant managers and assisted by a hierarchy of eunuchs, one that was parallel in organization and function to the formal bureaucracy staffed by Confucian scholar-officials.8 Yet the nominal distinction between private and public is deceptive. The salt monopoly and the customs bureau, two of the department’s most lucrative operations, are veritable public state functions in today’s world as in the Chinese imperial tradition.

The scale and variety of the commercial activities conducted by the department are staggering, ranging from managing the imperial land estates and extending loans to salt merchants, to operating pawn shops and trading in jade, silk, copper, ginseng, fur, Korean paper, and other commodities. Backed by imperial power, it enjoyed an unnatural advantage over the big merchant houses with which it competed for market share and profit. The modest name of Imperial Household Department belies the fact that it was a tariff authority, manufactory, trading house, real estate developer, commercial bank, and investment fund rolled into one, with cash assets reaching ten million ounces of silver in the early Qianlong years and an annual profit of 600,000 to 800,000 ounces of silver.9 Magnifying its power, and further blurring the demarcation between the public and the private, the emperor often transferred bondservants from the department to posts in the regular bureaucracy. At the end of its formative era with the passing of Emperor Yongzheng in 1735, the rank of its managers reached the sizable number of 1,285.10

The corps of bondservant managers who operated such a vast manufacturing and commercial enterprise boosted a broad spectrum of managerial and technical skills. Characterized by a pragmatic problem-solving disposition, they constituted a new “technocratic” ruling elite who wielded the power of techne with a visibility in court and society that had no parallel in the previous dynasties. Leaders of a “logistical and epistemic culture of working” in which the efficacy of work surpassed the authority of words, they perpetuated what Chandra Mukerji has called “logistical power” and elevated it to parity with text-based scholarship in the Confucian hermeneutic tradition.11 Although far fewer in number than the scholars, their institutional advantage allowed the bondservants to have a disproportional impact on society.

Both the recruitment and training of the bondservants as well as the organizational culture of the department were products of the historical experience of the Manchus, especially its innovative system of military-cum-civil organization called the Eight Banners. The Manchus, an ethnic minority group on the northeastern border of the Ming empire, rose to prominence in the late sixteenth century. As the loose federation of Manchu clans expanded by subduing its neighboring peoples from the 1580s through the 1620s, the subjugated were pressed into military service and organized into parallel banners after the Manchu prototype: one eight-banner set of Mongols and another of Han Chinese (called Hanjun, or Chinese-martial). All twenty-four banners achieved the hereditary status of privilege after the conquest of the Ming in 1644 and 1645.

Within each banner group there were three categories of people: the rank-and-file, bondservants, and household slaves.12 The bondservants (booi in Manchu, meaning “of the house”) were slaves or servants of various ethnicities, mostly captured in battle. Grouped within each banner in units called “arrows” (niru), bondservants performed such menial tasks as fishing, gathering honey, and farming their lord’s estate, as well as serving as bodyguards at home and field assistants in battle.13 After the conquest, their descendants who belonged to the emperor’s house, or booi from the Three Superior Banners, became the mainstay of the Imperial Household Department. In structure, responsibilities, and personnel, the department can be said to be an extension of the earlier booi organizations.14

The nature of servitude of the imperial bondservants is particular and contained, almost paradoxical: personal slaves in perpetuity to the emperor, they were highly privileged in fact, albeit not in name. Special schools in the capital were established after the conquest to train them in the civil and military arts as well as a range of specialized skills.15 The best graduates received appointments as clerk (bitieshi) and worked their way up the department hierarchy, or took the civil service exam and became high-ranking officials in the regular bureaucracy. Bondservants could own property, titles, and their own slaves.16 In the eyes of the rest of society, the imperial bondservants constituted an elite corps with privileged access to the ultimate center of power. They were the only group in the empire who enjoyed access to the powers of both the emperor’s personal bureaucracy and those of the formal bureaucracy, where quotas were reserved for them.17

Their generations-long servitude to and intimacy with their lords rendered the bondservants singularly trustworthy in the emperor’s eyes, especially in handling such sensitive matters as money, manufacturing, or the European scientific experts in court.18 The geographical concentration of the booi—the majority settled in Beijing, Shenyang, Chengde, and the imperial estates in Manchuria after conquest—as well as their hereditary status also fostered a close-knit camaraderie with a sustained culture of shared practical knowledge. In all of these aspects the bondservant could not have been more different from the Chinese scholars.

THE MIND OF THE POTTER: TANG YING AND SHEN TINGZHENG

Tang Ying (1682–1756), the supervisor of the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory from 1737 ...