![]()

JOHN CHARLES FRÉMONT, THE GREAT PATHFINDER, CONQUERED PLENTY of mountain ranges in his nineteenth-century explorations of the West. Perhaps none was more thrilling than his August 1842 ascent of Wyoming's Wind River Range. Champion of Romantic prose and his own heroic persona, Frémont articulated the sheer drama of nature's fundament in the West and realized the role it played in defining the region's character in the national imagination:

We continued climbing, and in a short time reached the crest. I sprang upon the summit, and another step would have precipitated me into an immense snow-field five hundred feet below…. It is presumed that this is the highest peak of the Rocky Mountains. The day was sunny and bright, but a slight shining mist hung over the lower plains…. On one side we overlooked innumerable lakes and streams, the spring of the Colorado…and on the other was the Wind river valley, where were the heads of the Yellowstone branch of the Missouri; far to the north, we just could discover the snowy heads of the Trois Tetons, where were the source of the Missouri and Columbia rivers…. Around us, the whole scene had one main striking feature, which was that of terrible convulsion. (Frémont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, 69–70)

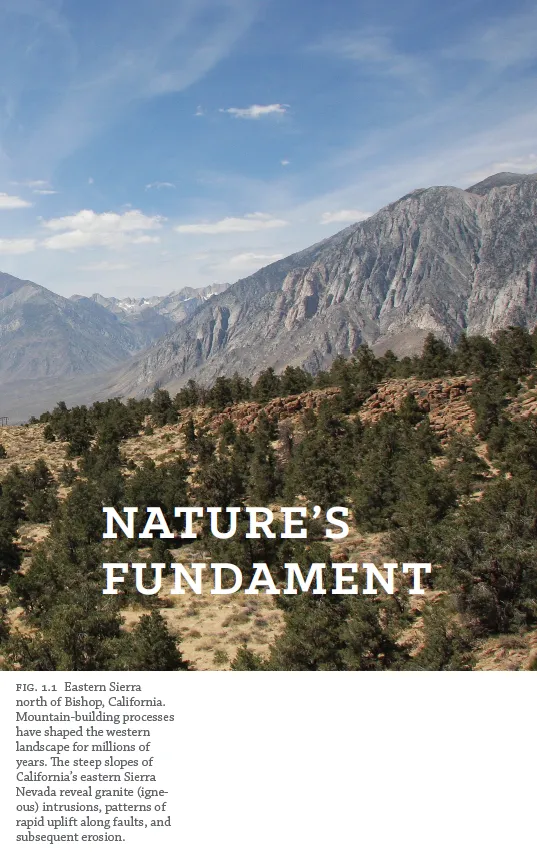

Much of the West's appeal remains connected to its physical musculature, its sheer material, visceral presence. The size and heterogeneity of the West can be overwhelming, exhausting, and exhilarating. Some of the West's most dramatic, rugged landscapes can be enjoyed (with perhaps less drama than Frémont describes) on a trip along U.S. 395 between Reno, Nevada, and Los Angeles, California. The road passes just east of the great, granite-faced Sierra Nevada, probing the mountains at times near Mono and June lakes, and then making the long descent toward Bishop into the arid, mountain-rimmed Owens Valley. Looking south from near Sherwin Summit, you can still be reminded of one of the West's great defining elements, the omnipresence and scale of its landforms (fig. 1.1). Frémont had it right: mountains, open space, and the overwhelming visible signatures of geological forces are the quintessential elements of the region's physical geography and enduring parts of why many people are drawn to the West.

Nevertheless, nature's fundament in the West has everywhere been modified by human action and intent, often over long periods of time. Even what seems at first glance to be a natural landscape has been shaped by culture and technology: California's rolling hills are populated by exotic European grasses, and high-country conifers in the Rockies may have been modified by human-caused fires and nineteenth-century logging. At the same time, the West's cultural landscapes are embedded within a larger environmental context. A California farm field still needs to be anchored in the requisites of soil and water, and every western suburb creates its own ecology of plants and animals. This section of the field guide focuses on elements of the natural world that have contributed to the West's regional identity, shaped our daily lives, and become interwoven into the region's cultural fabric.

What are the defining elements of the West's natural environment? The region's geological setting and topography (terrain and landforms) are extraordinarily complex, a function of the West's complicated and often-fractured position on the Earth because of the ways tectonic plates have collided (the region is a contact zone between the North American and Pacific plates) and fragmented to produce the diversity we see today.

Whether you are looking at coastal Washington's Olympic Mountains or southeastern New Mexico's Pecos Plains, it is helpful to keep some basic ideas in mind. What is visible today is only a snapshot in geological time, the most recent expression of processes of mountain building, erosion, and change that have been at work for millions of years. As the geologists remind us, if all geological time since the beginning of the Cambrian period (almost 600 million years ago) were embraced in a calendar year, the first mammals would appear in late August, the first primates in early December, and modern humans on New Year's Eve. When we look at that Victorian-era house in the “old” part of town, we should remember how recent such cultural signatures are in comparison to the bedrock they are sitting on.

While you can find exposed examples of rocks that are more than one billion years old (such as the 1.7-billion-year-old Vishnu schists at the bottom of the Grand Canyon), much of the ancient geological foundation in the West has been covered by more recent sedimentary and igneous deposits. Overall, much of the West's surface geology is relatively young. In terms of our geological year, for example, the Rocky Mountains don't show up until late November (about 60 million years ago) and the glaciers don't appear until about December 28 (within the past 2.5 million years). The distinctive granite core of California's rugged Sierra Nevada (fig. 1.1) did not experience its major thrust skyward until about 4 million years ago. Similarly, the lava beds that cover much of the Columbia Plateau and Snake River Plain in the interior Pacific Northwest are recent additions, dating from about 2 million to about 30 million years ago. Indeed, active Cascade volcanoes, such as Mount Saint Helens in Washington (which erupted in 1980), continue to make new landscapes today.

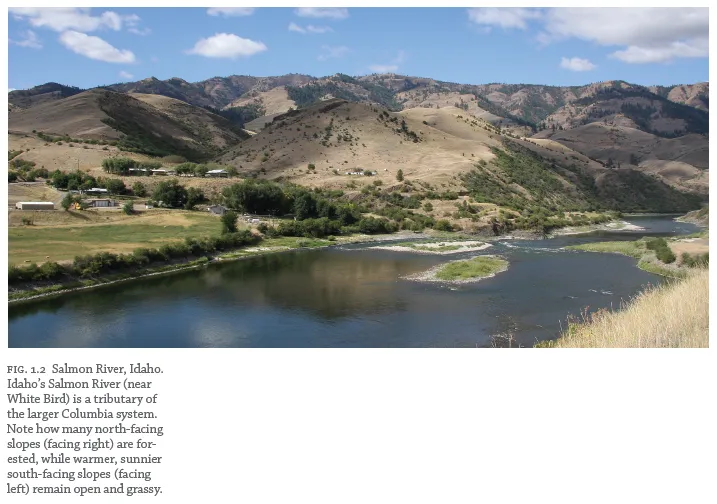

Water and major drainage basins also play key roles in organizing the region's physical and human geography (fig. 1.2). Much of all life in the West is concentrated within reach of the fragile ribbons of surface water that trace their paths across this largely arid land. In addition, the Continental Divide snakes across the West, from southern New Mexico through northern Montana, separating the drainage of the region into the Pacific and Atlantic basins. Being west or east of that line can have profound implications for weather patterns, vegetation, and agriculture.

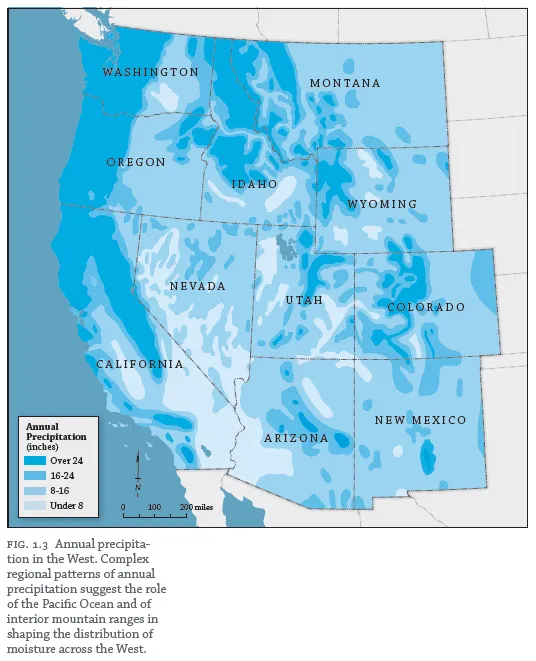

The varied climates, unpredictable weather, and overall atmospheric conditions create additional landscape signatures in the region. Wide-open spaces are defined by the clarity of the air, the prominence of sunshine, and a high, well-defined sky. Clouds gather along west-facing mountain ranges as moisture is forced upward and condenses, while nearby valleys to the east may remain dry. A simple map of western precipitation is a reminder of how much moisture is squeezed out by the region's higher uplifts and how plants, animals, and people within the Columbia Plateau, Great Basin, and High Plains areas must inevitably adjust to their position on the drier, leeward side of the nearby mountains (figs. 1.1 and 1.3). The wet sides of the Cascades, Sierra Nevada, and Rocky Mountains accumulate between twenty-five and fifty inches (and sometimes more) of moisture annually, much of it in the form of snowpack, while portions of eastern Oregon, southeastern California, and Colorado must make do with fewer than ten inches a year.

Western vegetation is an elegant expression of the complex, nuanced relationships between climate and topography as well as a result of the local effects of soil type, slope, and drainage. Some plants have become iconic regional landscape symbols—consider cacti and Joshua trees, sagebrush, and conifers—and changes in vegetation, often influenced by people, are a part of the story in almost every western landscape. Wildfire, for example, is a significant natural and cultural element across the western landscape, and its frequency in grasslands or forests profoundly influences the species composition of these environments. Similarly, exotic and invasive plants introduced by accident or on purpose can rapidly rework the vegetative landscape.

More generally, what explains the difference between the oak-studded grasslands of central California's Coast Ranges (fig. 1.4) and the subalpine fir and spruce forests of Montana's Glacier National Park (fig. 1.5)? On a regional scale, both latitude and proximity to the Pacific Ocean are pivotal considerations. Different seasonal patterns of temperature and precipitation shape opportunities for vegetation—and agriculture—at 33 degrees north latitude (southern New Mexico) and at 48 degrees north latitude (north-central Montana). Similarly, maritime settings such as western Oregon or the northern Salinas Valley in California offer ecological niches that reflect the modifying impact of the sea—frequent fogs, cooler summers, warmer winters—while continental settings such as eastern Arizona or central Wyoming offer niches that reflect greater daily and annual variability, especially hotter summers and colder winters.

Elevation is an essential ingredient in understanding western landscapes, particularly vegetation. Western topography profoundly influences average temperatures, which generally fall about three or four degrees Fahrenheit with every thousand-foot rise in elevation, a...