- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

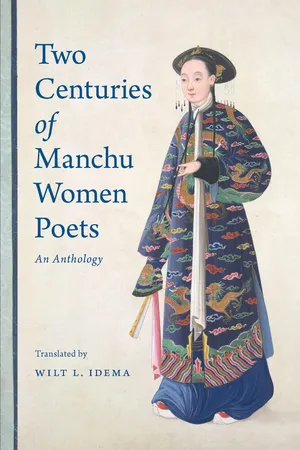

This anthology presents substantial selections from the work of twenty Manchu women poets of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The poems, inspired by their daily life and reflections, provide fascinating insights into the experiences and emotions of these women, most of whom belonged to the elite families of Manchu society. Each selection is accompanied by biographical material that illuminates the life stories of the poets. The volume's introduction describes the printing history of the collections from which these poems are drawn, the authors' practice of poetry writing, ethnic and gender issues, and comparisons with the poetry of women in South China and of male authors of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Two Centuries of Manchu Women Poets by Wilt L. Idema in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Histoire de la Chine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Women of the Nalan Family

Miss Nalan, Sibo, and Madam Zhaojia

MISS NALAN WAS NOT THE EARLIEST MANCHU WOMAN POET. We know the names of several others of the Kangxi period (1662–1722), and in some cases we also know the titles of their collections, but usually only one or two poems have been preserved. This makes Miss Nalan the earliest Manchu woman poet whose collection has survived in its entirety. Its title, Poetry Drafts from Leisure after Needlework (Xiuyu shigao), echoes the titles of many other collections by women poets and stresses that poetry was only an avocation—she would turn to the writing of verse after she had finished her work for the day.

As the youngest daughter of Nalan Ming-zhu (b. 1635–1708), one of the richest Manchu officials of the late seventeenth century, Miss Nalan was a younger sister of the well-known male poet Nalan Xing-de (1655–1685). Her slim collection of poetry was published following her death with a preface by her nephew Yong-shou (1702–1731), the adopted son of her elder brother Kui-xu (1674?–1717). Yong-shou’s wife Sibo would, as a widow, also author a modest collection of poetry titled Preserved Together: Selected Poems (Hecun shichao). Preserved Together contained not only her own poems, but also those of Gong Danting, the woman she had hired as teacher of her daughters. In the small collection of prose essays that Sibo published some years later, we also find an essay by one of her daughters.

Ming-zhu was a close confidant of the Kangxi emperor. He was one of the few officials who supported the emperor in his confrontational policy toward Wu Sangui (1612–1678), the Ming general who in 1644 had admitted the Manchus inside the Great Wall and had been rewarded for his role in the Qing conquest of the empire with a semi-independent kingdom in Yunnan and Guizhou. When the confrontation resulted in the so-called Rebellion of the Three Feudatories (1673–1681), Ming-zhu rose to become grand secretary in 1677 and used his position to greatly enrich himself. In 1688 he and his clique were accused of corruption and Ming-zhu was forced to step down, but he continued to enjoy the emperor’s favor and increased his possessions by investing in the government-controlled salt trade.1 His descendants enjoyed great wealth until in 1790 Kui-xu’s great-grandson Cheng-an was stripped of all his positions at the instigation of He-shen (1750–1799), at that time the all-powerful favorite of the Qianlong emperor, after which all family property was confiscated. The family’s mansion too was confiscated at that time and redesigned for use as a princely palace. Known as the Chunqinwang Fu, it is presently one of the best preserved princely palaces of the Qing. When Cao Xueqin’s novel Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou meng) became widely popular in the nineteenth century, one theory, claiming no less an authority than the Qianlong emperor himself, held that the novel’s descriptions were based on life in the Ming-zhu household.2

Ming-zhu patronized Chinese officials and scholars and saw to it that his sons received an excellent education.3 His eldest son, Xing-de, served the emperor as a personal attendant and quickly rose through the ranks, but died at a relatively early age. He is known to this day as the finest lyricist of the Qing dynasty.4 Some of Xing-de’s sons and grandsons would continue to serve the dynasty in high positions. Ming-zhu’s youngest son, Kui-fang, died at a relatively early age too. He was married to the eighth daughter of Giyesu, Prince Kang (1645–1697), a great-grandson of Nurhaci, who was in charge of the southeastern front in Fujian during the Rebellion of the Three Feudatories. When the princess quickly followed Kui-fang in death, the couple’s two young sons (Yong-shou and Yong-fu) were entrusted to Kui-xu, who had no sons of his own. (From a poem by Sibo we learn that the grandparents, though now officially granduncle and grandaunt, remained in close contact with their grandsons and their wives.) Kui-xu had started out in his career as a member of the emperor’s bodyguard, but because of his conspicuous literary talents, he was quickly moved to the Hanlin Secretariat, and served as its chancellor from 1703 till his death, on occasion also concurrently holding other high positions. Kui-xu not only left a large collection of his own poetry, but at the emperor’s behest also compiled a small anthology of women’s poetry titled Fine Poems by Women of Successive Dynasties (Lichao guiya).5

This collection in twelve juan is a highly selective anthology of shi poetry from the Tang to the Ming dynasties. The poems are divided by genre (five-syllable old style poetry; seven-syllable old style poetry; five-syllable regulated poems; seven-syllable regulated poems; five-syllable quatrains; seven-syllable quatrains; and miscellaneous forms). Within each genre the poems are arranged by dynasty, and for each dynasty the poets included are arranged in the order of empresses and imperial concubines, well-born ladies and concubines, nuns and courtesans, foreigners and the spouses of local rulers. The collection carries no preface in its 1703 edition, but includes a detailed set of “editorial principles” (fanli). Kui-xu stresses for instance that he has omitted all poems of questionable authorship. The final item of these editorial principles reads:

The rise of literature is related to orderly administration. Our Sovereign the Emperor has scrutinized the past: if one completes the wide world by the privileging of transformation through culture one will not only see a proliferation of human talents but also witness of a multitude of masters because of mutual competition. And those who wield the brush to compose their texts in the inner chambers will often be able to compete with men of letters. It is therefore our intention to collect the poems of well-born ladies of the present age and to compile a matching volume to record that the transformation by civilization of this Sagely Era even among women is capable of proclaiming the glory of this dynasty!6

Unfortunately, such a second collection, in which Kui-xu could have included a fair sample of the poems by his younger sister, never saw the light of day, because Kui-xu died the year Fine Poems was published. The project to compile an anthology of women’s poetry that manifested the universal civilizational mission of the Manchu Qing dynasty was only undertaken one century later by Yun Zhu.

Kui-xu may well have been motivated to consider the compilation of a collection of poetry by women of the Qing because he was surrounded by highly literate women in his own family. These included not only his younger sister but also his mother and his wife. Ming-zhu’s wife (1637–1694) was a daughter of Ajige (1605–1651), one of the major Manchu generals in the conquest of China.7 She married her husband at the age of fifteen, when her husband was only seventeen. From her grave inscription we learn that she was literate both in Manchu and Chinese.

In her youth, her ladyship learned the national script and was not yet acquainted with Chinese characters. But when she later made up her mind to study them, she could completely understand [a text] on first reading. She loved to read works such as the Comprehensive Mirror and A History of Women, and when practicing calligraphy she excelled in the regular script.8

The grave inscription proceeds with a description of the excellent care she took of the scholars her husband hired for the instruction of their sons, mentioning that she would attend the lectures on occasion from behind a screen. She is also highly praised for her philological acumen, and was a pious Buddhist:

In her daily life she had taken refuge with the Buddha, and each morning on rising she would burn incense, make her devotions, and recite one roll of scripture. When she once had copied out the Diamond Sutra, her handwriting was so perfect that it was distributed in print, and both clerics and laypeople revered these copies as exceptional treasures.9

Despite this piety we learn from another source that she was a jealous woman. When her husband took a fancy to a serving girl and praised her eyes, she had those eyes gouged out and presented them to her husband in a box. At least one modern scholar is willing to give credence to the account that she died because of the wounds she suffered when the girl’s father tried to take revenge.10

Kui-xu’s own wife Lady Geng (1671–1719) was a daughter of Geng Juzhong (d. 1687), a younger brother of Geng Jingzhong (d. 1682). When his older brother rebelled as one of the Three Feudatories, Geng Juzhong stayed loyal to the Qing and informed on his brother even after the latter had submitted. Lady Geng’s mother was an imperial princess, and throughout her life she would continue to frequent the imperial palace; the Kangxi emperor was quite fond of her. Her grave inscription praises her for her moral seriousness from an early age:

From birth she displayed a preternatural intelligence, and her sharp understanding was beyond compare. From her infant years her behavior was correct and composed like an adult. In her youth and once an adult she read books such as Inner Rules, and she needed only to...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology of Dynasties and Qing Reign Periods

- Dates and Names

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. The Women of the Nalan Family: Miss Nalan, Sibo, and Madam Zhaojia

- Chapter 2. A Prisoner’s Mother and Wife: The Mistress of the Study for Nurturing Simplicity and the Mistress of the Orchid Pavilion

- Chapter 3. Chastity and Suicide: Xiguang

- Chapter 4. Mourning Royalty: Lady Zhoujia, Lady Tongjia, and Lady Fucha

- Chapter 5. Sacrifice and Friendship: Bingyue

- Chapter 6. A Tomboy in a Silly Dress: Mengyue

- Chapter 7. Unbridled Energy: Yingchuan

- Chapter 8. Releasing Butterflies: Wanyan Jinchi

- Chapter 9. Seeking Refuge in Truth: Guizhen Daoren

- Chapter 10. Traveling throughout the Empire: Baibao Youlan

- Chapter 11. A Proud Descendant of Chinggis Khan: Naxun Lanbao

- Chapter 12. From Hengyang to Beijing: Lingwen Zhuyou

- Chapter 13. The Modest Pursuit of a Minor Way: Duomin Huiru

- Chapter 14. A Poet from the Homeland: Lady Husihali

- Abbreviations

- Notes

- Glossary of Chinese Characters

- Bibliography

- Index