![]()

CHAPTER 1

At the Place Where the Cascades Fall

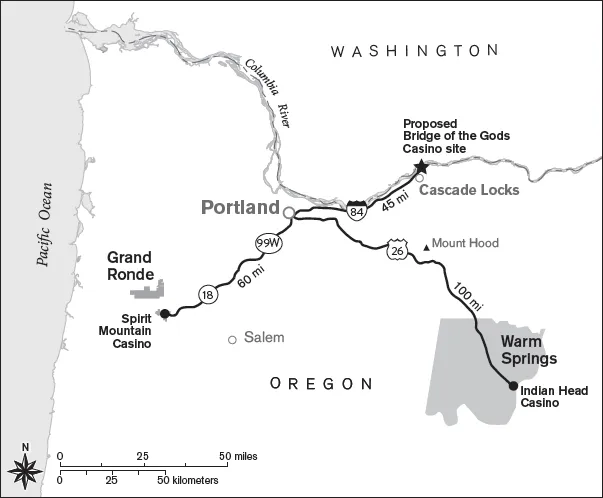

THIS STORY BEGINS WITH A PLACE. THE CASCADE FALLS IS A GEO-graphic location in the Columbia River where it flows westward between present-day Oregon and Washington states, in an area known as the Columbia River Gorge. It was identified in two treaties negotiated in the 1850s between the United States and Native peoples who would afterward become the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. The section of the river that contains the Cascade Falls, sometimes called the Cascade Rapids, runs alongside the present-day city of Cascade Locks, Oregon, located approximately halfway between Portland and the city of The Dalles, Oregon, accessible from Interstate 84. It was here, in Cascade Locks, that the Warm Springs tribe proposed to build a casino, the Bridge of the Gods Columbia River Resort Casino, in a bid that would extend for fifteen years (1998–2013).

The place where the cascades fall is a site of tremendous change. Though accounts vary, Native peoples from along both sides of the Columbia River have stories in their oral traditions about the Bridge of the Gods, an ancient land bridge that resulted from a massive landslide in this location. One of these stories speaks to an ongoing conflict between two brothers, Wy’east and Klickitat, who had everything they needed to be satisfied but still fought over land, resources, and power, much to the displeasure of Great Spirit. This story offers a history of place while also embodying lessons about how people from the river should and should not behave according to their distinct cultural tradition. The legend, which ultimately ends when the two brothers are turned into mountains, conveys a warning against conflict and jealousy.1

In time, the force of the Columbia River eroded the famed Bridge of the Gods, and the rapids that resulted became prime fishing sites for Native nations that lived along the river. Chinook peoples residing along the river orchestrated an extensive trade network, had highly developed fisheries, and managed vast resources. In addition, they formed economic, social, artistic, and political relationships with other Native nations over generations. Shortly after American settlement violently displaced many Native nations from the region, the US Congress sought to make the river more navigable to increase travel and trade opportunities, and in 1896 it commissioned the Cascade Locks and Canal in order to make it possible for ships to travel up and down the river without having to portage around the falls. In the late 1930s, construction of the Bonneville Dam to generate electricity resulted in the total submersion of Cascade Falls, much to the distress of Native peoples who had steadfastly continued to practice a way of life that depended on fishing along the river and maintaining intertribal relations formed around this economy.2

MAP 1.1. Grand Ronde, Warm Springs, and Cascade Locks in relation to Portland

In 1998, the Warm Springs tribe sought to expand their gaming operations from their Indian Head Casino, opened in Warm Springs, Oregon, in 1995, to meet the economic needs of tribal members. After vetting several locations on their reservation in central Oregon as well as tribally owned trust lands in nearby Hood River, Warm Springs tribal leaders set their sights on an industrial park within the city of Cascade Locks. Though this land was neither part of the tribe’s historic reservation nor held in trust for the tribe, the location is culturally and historically significant to the Warm Springs people, and it is part of their recognized ceded lands where they have reserved treaty rights.3

Having chosen the location at Cascade Locks, Warm Springs leaders worked to secure trust land and a state-tribal compact so that they could build a new casino there.4 They hoped that a casino located closer to the Portland metropolitan area would generate more income than their modest Indian Head Casino, located on their reservation in an isolated and minimally populated region of central Oregon. Though Warm Springs had exhibited tremendous tenacity over many generations, the tribe was experiencing desperate economic conditions that many feared threatened their stability. The proposed Columbia River Gorge Casino represented possible long-term economic stability and much-needed employment opportunities for tribal members.

After Warm Springs proposed to build the casino in Cascade Locks, Grand Ronde, a Native nation located about sixty miles southwest of Portland, raised objections. By 2001, Grand Ronde tribal leaders had begun to lobby actively against it, arguing that gaming policy in the state allowed only one casino per tribe, and that the casino must be on reservation lands. Grand Ronde was just beginning to build infrastructure and was striving to heal from social and cultural ruptures resulting from multiple generations of disastrous federal law and policies, particularly termination legislation enacted in the 1950s, which ended the government-to-government relationship between some tribes and the federal government and was aimed at getting Native Americans to assimilate into the dominant society. Grand Ronde leaders felt that a Warm Springs casino in the Columbia River Gorge would draw customers away from Grand Ronde’s Spirit Mountain Casino and thus significantly and negatively impact Grand Ronde’s economy. They foresaw dire consequences for their people, as large revenue loss would require major cuts to programs and services for tribal members. Complicating matters, Grand Ronde leaders pointed out that their people too had historical and cultural ties to the land at Cascade Locks because one of their treaties also names the Cascade Falls as geographic boundary. They argued that they should have a seat at the table to discuss tribal economic development in that region.

These types of conflicts remain important to understanding the complex landscape that Native nations involved in the tribal casino economy must negotiate. Over the years, I have heard a number of tribal leaders wryly comment that for every ten problems solved by the income earned from this economy, nine new problems arise. While statements like these are anecdotal and hard to quantify, they do speak to the fact that tribal people sometimes feel that there are new, occasionally unexpected, and not always positive consequences of the casino economy on tribal communities. One such troubling consequence appears (at least on the surface) to be an increase in intertribal conflict that stems from intense debates about tribal casino policies and competition for limited state gaming markets.

While Native nations might prefer that their differences of opinion about casino politics in the casino era remain private, intertribal conflict has been covered regularly by regional and national media, and Native people and non-Natives alike have been quick to criticize. When Native nations in the gaming business become involved in actions such as opposing competing tribal casinos, disenrolling tribal members, and blocking unrecognized tribes’ applications to gain federal recognition they are often charged with being solely motivated by greed and self-interests.

Consistent with national trends, Native nations in Oregon have experienced intertribal disagreements that appear to stem from the tribal casino economy. For instance, Grand Ronde and the Cowlitz Indian Tribe of Washington State have been involved in a multiyear debate over Cowlitz’s plan to build a Class III casino in La Center, Washington, and the Cow Creek and Coquille Indian Tribe have disagreed over the latter’s plans to open a Class II casino in Medford, Oregon.5 Though Native nations have often worked together to protect and expand their sovereign rights, increasingly Native nations in the casino era are employing new tactics to protect their investments, including litigation, alliances with federal and state government officials, and partnerships with nongovernmental organizations and citizen groups.

After Warm Springs proposed to build their casino in the Columbia River Gorge, particularly after setting sights on the Cascade Locks location, reporting on this topic in Portland’s Oregonian, the state’s most widely read newspaper, focused on the relationship between Grand Ronde and Warm Springs. This coverage progressively became framed in terms of conflict and competition.6 The newspaper harshly criticized Grand Ronde for opposing Warm Springs and portrayed Grand Ronde as a greedy competitor, hungry for the Portland metro area market. The dispute between Grand Ronde and Warm Springs was framed as another instance of Native nations fighting over casino markets. The discourse on tribal casinos as exemplified in the Oregonian has, for the most part, insufficiently contextualized tribal motivations and historical events that led to the creation of the casino economy.

A fair and accurate analysis of the tribal casino economy must take into account how ongoing projects of colonization continue to be manifest in contemporary forms. These new projects and power relationships maintain what semiotician and literary theorist Walter Mignolo calls “coloniality” or systems of “knowledge, beliefs, expectations, dreams, and fantasies upon which the modern/colonial world was built.”7 Projects of coloniality are visible in the media discourse around tribal casinos and in imagery generated about this economy, articulated in public forums, and manifested in policy that regulates it. The recognition of ongoing projects of coloniality provides an analytical tool that can help expose and deconstruct ideologies that racialize and marginalize Native people, forward false perceptions of tribal histories, work to limit economic opportunities, and reproduce legal fictions that undermine tribal sovereignty. As environmental scientist Elisabeth Middleton argues, “This is not a disempowering, victimized perspective, focused simply on colonialism and its ongoing manifestations. Rather, it is a stance of liberation: recognizing coloniality acknowledges the entrenched subtleties of colonialism that linger in both formerly colonized and colonizer societies, and this acknowledgement offers a pathway toward the conscious development of decolonial institutions and ideas.”8

As Middleton suggests, explicit recognition of the continued presence of coloniality entrenched in systemic manifestations of violence, marginalization, and oppression is not the final goal. Once projects of coloniality are named, the task must turn to both internal and external forms of decolonizing, or “countering the devaluation of indigenous identity, knowledge, and lifeways that came with colonialism.”9 Notably, decolonization as a social and cultural process asks Native peoples to rethink and reframe their perceptions of themselves through a decolonized lens. An approach of this sort would encourage tribal leaders to examine holistically the events and experiences of coloniality that shape and affect their contemporary lives, understand how these forces have in some cases reordered intertribal relations, and forward decolonized policies (economic and otherwise) that align with Native peoples’ values, identities, knowledge, and ways of life.

Using a decolonizing framework, this book explores the colonial logics entrenched in the tribal casino discourse as well as the ever-present, complex, and sometimes even contradictory ways in which Native nations have engaged in struggles for sovereignty and self-determination. Examining the histories leading up to the events that followed the Warm Springs Bridge of the Gods Casino proposal, the book illuminates ruptures in tribal life caused by federal and state laws and policies, explores the impact of the non-Native public and mainstream media in framing tribal relationships, and accentuates powerful histories of survival embodied in modern Native nations. On this basis the examination of intertribal conflict also reveals possibilities for intertribal cooperation in the casino era.

Ultimately I argue that, while the tribal gaming economy has reframed tribal-federal and tribal-state relationships, it has also reframed tribe-to-tribe relationships. Critically examining intertribal tensions in the casino era brings into sharp focus deeply normalized systems of inequality (colonial-settler logics) that continue to permeate both Native and non-Native thinking on the topics of Indian gaming and intertribal conflict. As such, I argue that the circumstances that lead to intertribal conflict are directly influenced by complex social events and structural systems that are sustained by external governments, public opinion, and the media. I maintain that the assertion of the rights and interests of any single Native nation by opposing another Native nation’s assertion of their rights and interests, though seemingly effective in the short-term protection of economic resources, actually works against long-term goals of decolonization, which requires the return of land, resources, power, and rights to Indigenous peoples.

Using a case study approach focused on the relations of two Native nations in Oregon, my research offers a decolonizing and critical intervention into the tribal casino discourse by placing Indigenous peoples’ knowledge at the center of this inquiry. As such, this book’s central argument is that while intertribal conflict in the casino era is often framed as a consequence of tribal corruption and greed, even framed this way at times by Native people, it cannot be understood without a deeper analysis of Indigenous peoples’ perspectives on and interpretations of the historical, social, and political conditions that produced contemporary tribal communities, the tribal casino economy, and the intense politics on and off the reservation over tribal gaming. Contemporary tribal concerns (including intertribal conflicts over casinos) cannot be separated from the complex legal structures and historic events that underlie the lived experiences of tribes in Oregon. Through the years, Warm Springs and Grand Ronde have responded to the same federal laws and policies, intermingled with the larger non-Native public, and adapted strategies to survive as separate peoples.10 Though all tribes across the country have had to react and respond to shifting policy eras, Grand Ronde and Warm Springs have shared more closely a regional outgrowth of colonialism, one unique to Oregon.

While there exist many parallels and shared experiences between Grand Ronde and Warm Springs, they also have distinct and divergent histories. For example, over twenty-seven distinct tribes and bands would become Grand Ronde, including the Chasta, Kalapuya, Molalla, Rogue River, and Umpqua.11 Several distinct tribes negotiated treaties in the mid-nineteenth century, though many of these were not ratified due to intense pressure from Congress to have the lands in western Oregon cleared for settlement.12 Treaties that were finally ratified did not include reserved rights language or, in most cases, the exact details of where a tribe’s reservation would be located. Comparatively, Warm Springs consists of three tribes, the Wasco, Warm Springs, and Northern Paiute peoples. In 1855, the Warm Springs and Wascoes negotiated one treaty with the federal government that clearly defined the tribes’ reserved rights and reservation boundaries, and this treaty was ratified by Congress. Once the tribes relocated to the reservation in central Oregon, Warm Springs was fairly isolated from the broader settler society. Grand Ronde, however, experienced continuous pressure from nearby settlers who coveted the community’s lands and resources in densely populated western Oregon. In the 1950s, tribal experiences again differed as Grand Ronde’s government-to-government relationship was terminated by an act of Congress, and Grand Ronde tribal members were no longer eligible to participate in federal Indian programs, no longer had a recognized tribal government, and were denied federal protection of their lands and resources. Meanwhile, Warm Springs successfully defended against termination legislation.13 As a result of both parallel and divergent tribal experiences, the tribes are unique in their responses to economic opportunities, and this contributes to how each perceives the tribal casino economy and participates in it. Though both eventually entered the tribal casino economy in 1995, they did so from very different historical, economic, and political standpoints.

These convergences and divergences recall the main themes from the story about the Bridge of the Gods. In light of this story and its multifaceted teachings, it is perhaps poignantly fitting that a conflict between Native nations over land, power, and resources...