- 283 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Environmental Toxicology

About this book

Organic and inorganic chemicals frequently exhibit toxic, mutagenic, carcinogenic, or sensitizing properties when getting in contact with the environment. This comprehensive introduction discusses risk assessment and analysis, environmental fate, transport, and breakdown pathways of chemicals, as well as methods for prevention and procedures for decontamination.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Environmental Toxicology by Luis M. Botana in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Natalia Vilariño

1High-throughput detection methods

1.1Introduction

High-throughput detection methods are experimental techniques that involve automated tools and allow rapid acquisition of data related to the presence or absence of a certain molecule or group of molecules. They are often referred to as high-throughput technologies or high-throughput screening (HTS) in the literature. These methods provide a remarkable increase of productivity when compared to traditional detection methods. Currently, high-throughput terminology is applied to processing of hundreds of samples in a short period of time.

These methods often comprise several approaches to achieve high workflow rates, among them laboratory automation, miniaturization and parallelization of detection technologies, effective experiment design, continuous processing, and computerized data interpretation. Although many of them have been developed for pharmaceutical screening of high numbers of products, they are also suitable for the detection of environmental contaminants.

This chapter will provide an overview of laboratory automation, detection technologies, and experimental design compatible with high-throughput detection using nonanalytical methods. Analytical methods will be presented in Chapter 2.

1.2Laboratory automation

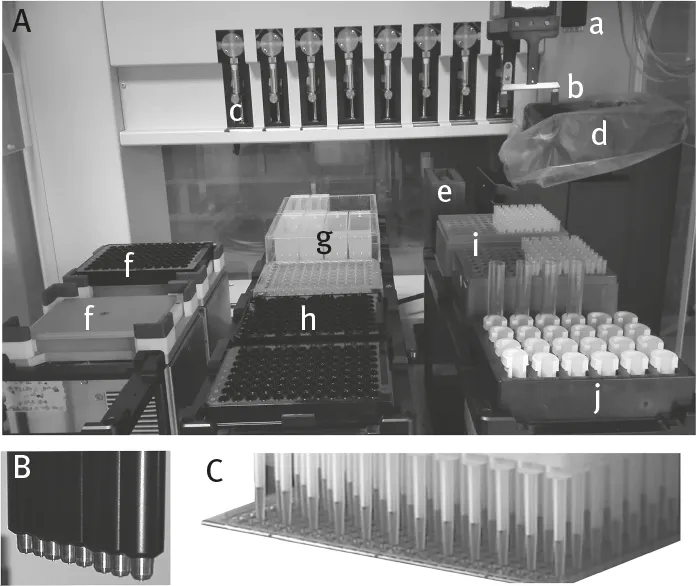

Laboratory robots are essential tools for handling high numbers of samples. Simultaneous assay of hundreds of samples is often performed in 96-, 384-, or 1536-well plates (Figure 1.1). Manual handling of 384- or 1536-well plates or several 96-well plates in parallel is impractical if not impossible (Figure 1.1) [1, 2]. Therefore, automated liquid handling is necessary for actual high throughput. Adequate programing will allow one to perform an experimental protocol simultaneously in a high number of samples. Currently, automated liquid handlers, dispensers, and workstations can effectively dispense liquids with high precision and good reproducibility in 96-, 384-, or 1536-well plates (for a review of liquid-handling technologies and principles see [2]). Automated workstations also perform sample transfer, tip replacement, incubations or mixing and shaking, depending on the device design and programing (Figure 1.2A). These instruments have pipetting arms with many-channel heads that allow parallel transfer of samples or reagents (Figures 1.2B and 2C). They are often endowed also with gripper arms to perform different tasks such as moving labware (tubes or plates) to different points of the station or removing plate lids. The pipetting and gripper arms can move along X-, Y-, and Z-axes across a stationary deck. In some instruments volume measurement systems have been incorporated as feedback quality controls for precision and accuracy of pipetting or dispensing [2].

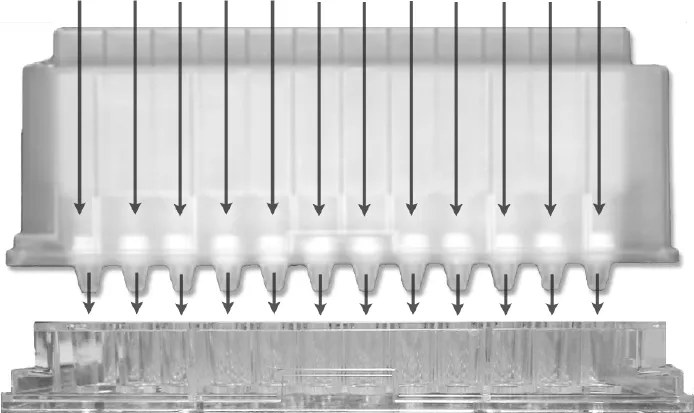

Automated laboratory workstations have been used mainly to execute detection assays in high numbers of samples before taking them to a reader. However, sample preparation previous to assay or analysis is often a bottleneck in most laboratories that slows down workflow [3]. Sample preparation automation is critical to ensure high-throughput turnover of detection methods, including quantitative analytical techniques. Automated solid-phase extraction (SPE) procedures for sample cleanup have been developed for online and offline processing. Robots may be used for exchange of disposable online SPE columns. Alternatively, versatile liquid-handling SPE workstations allow simultaneous offline sample processing through 96- or 384-well SPE plates (Figure 1.3) using robot-operated vacuum manifolds [1]. Both online and offline SPE provide similar limits of detection, ranges, accuracy, and reproducibility; however online methods allow lower amounts of sample [3].

Many workstations include bar code readers which are critical for automated sample identification and tracking. The generation of log files related to protocols and sample tracking are also useful for quality control and auditing.

Laboratory robots and workstations are required to warrant high productivity rates in high-throughput detection methods, but they also reduce contamination and eliminate human error [1]. Moreover, these techniques help to optimize laboratory personnel hands-on time and save costs by scaling down volumes. However, programing of complex experimental procedures is not trivial, in spite of user-friendly platforms, and miniaturization of plate wells should be makes them highly sensitive to dust, air bubbles, and evaporation [2]. In addition, liquid-handling conditions must be adjusted to avoid dripping and cross-contamination, and optimized sometimes for application-specific solutions, such as aqueous buffers containing different detergent concentrations or viscous material [1, 2].

1.3Miniaturization and parallelization of detection technologies

Miniaturized assay formats for high throughput require readers capable of simultaneous detection of miniaturized-well plates. There are many instruments in the market that provide data for 96-, 384-, and 1536-well plates in minutes. Many plate readers are endowed with different detection technologies. Multimode readers may include several of the following: absorbance, fluorescence, luminescence, fluorescence polarization, time-resolved fluorescence (TRF), time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET), and image-based cytometry.

Spectrophotometric absorbance measures how much light a chemical substance in solution absorbs (Figure 1.4A). The absorption spectrum (wavelength range of the light absorbed) is characteristic of each molecule.

Fluorescence occurs as a result of absorption of the energy of an excitation photon by a fluorophore (molecule with fluorescence properties, F in Figure 1.4B), which creates an excited electronic state S1ʹ (Figures 1.4B, C). Some energy is dissipated coming to a S1 energy state, and after a few nanoseconds the fluorophore returns to its ground state S0 by emitting a photon that has lower energy and, therefore, higher wavelength, than the excitation one (Figure 1.4B, C). When fluorescence intensity is measured, excitation occurs simultaneously with emission detection. TRF consists of emission measurement a few milliseconds after excitation. Although TRF reduces background signal significantly, it requires specific fluorophores with prolonged emission properties such as lanthanides, and the instrumentation and reagents needed for TRF are more expensive.

Fluorescence polarization is based on the fact that if a fluorophore is excited by polarized light, the emitted light will be depolarized if the molecule is rapidly rotating (Figure 1.4D). Small molecules rotate rapidly, while large molecules rotate slowly. Therefore, the interaction of small fluorophore-labeled molecules with large molecules can be detected by a reduction of emitted light depolarization (Figure 1.4D,E).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) consists in energy transfer from an excited fluorophore (donor, D in Figure 1.4F–G) to another molecule (acceptor, A in Figure 1.4F–G) without emission of a photon when they are in close proximity. The transference of energy occurs at small distances comparable to macromolecule size (Figure 1.4F, G), and when the acceptor fluorophore returns to its ground energy state, it emits a photon of different wavelength than the donor. Therefore, the interaction of one molecule labeled with the donor fluorophore with another molecule labeled with the acceptor fluorophore will result in quenching of donor fluorescent signal and appearance of acceptor fluorescence (Figure 1.4G). The same principle used for TRF applies to TR-FRET, which uses lanthanides as donors. TR-FRET provides additional information about conformation, flexibility, and equilibrium populations of interacting molecules [4].

Luminescence is the emission of light by a molecule. It really comprises any emission of light from an excited molecule when it returns to i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 High-throughput detection methods

- 2 Analytical instrumentation and principles

- 3 Quantitative and qualitative methods, primary methods

- 4 Toxicological studies with animals

- 5 Toxicological studies with cells

- 6 Marine Toxins

- 7 Cyanobacterial toxins

- 8 Isolation, characterization, and identification of mycotoxin-producing fungi

- 9 Analysis of environmental toxicants

- Index