![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Congested Online Ecosystem

The development of online advertising has been characterized by rapid growth, ingenious technological innovation, and restless entrepreneurialism that have spawned the proliferation of competing business models. But, novel technology and entrepreneurial initiative aside, the essence of the business, as with any other advertising medium, is to present a compellingly effective ad to the right person at the right time and place for a price that makes sense to the seller and potential buyer. For the principals, the advertisers and publishers, as Sam sang in Casablanca, “the fundamental things apply.”

Yet optimizing those fundamentals for a radically new digital medium has proved very complex. While, in less than twenty years, online advertising has become a substantial share of all advertising in the United States, its growth has been more like an uphill battle than a superhighway, at least when it comes to making money. Why?

One reason is that it’s “same old, same old.” That is, it’s advertising. Some of the other reasons are that it’s new and different. It’s digital, dynamic, and interactive. First, let’s look at the same old, same old.

Everyone knows that advertising works. We have all been persuaded by an ad to buy something we hadn’t intended to buy. On the other hand, we all know that plenty of advertising doesn’t work. All of us have ignored ads. Furthermore, we have often seen ads for which we knew we were not the appropriate audience. So all of us have experienced the futility and wastefulness of advertising. This will be true when online advertising becomes as prehistoric as a Paleolithic flint knife.

Then, too, at times it’s hard to demonstrate the causal connection between advertising and the awareness or purchase of the products the ads are supposed to promote.

Because of this acknowledged wastefulness, and because the efficacy of advertising has sometimes been more apparent than proven, during adverse economic times, ad spending customarily finds itself in the crosshairs of companies’ cost cutters. Often, it’s the first category of spending to go to the corporate guillotine. In the bloodless jargon of the management consultant, it’s a “discretionary expense.”

Now let’s turn to those other reasons-what could be called “the penalty of novelty.” Online advertising, for a number of years, was something of a stepchild among ad media just because it was so new and different. Early in the Internet era, the content found on websites was derivative and pedestrian, just cut-and-pasted pages from print publications-often disparagingly called “shovelware.” The user experience in the early days of Internet browsing was dismally similar to that of the early days of cable TV. Moreover, without such highlights of cable advertising as the Ginsu knife,1 the ad content of early websites was also pretty lackluster.

These obstacles were compounded by the inertia inherent in a new advertising channel up for adoption. Ad sales were few, as were viewers. It was all so new. Career advertising agency executives didn’t understand the new medium. There was a well-entrenched, media-buying infrastructure that was unfamiliar with online advertising. In many agencies, let’s just say that developing online ads was not a great career move.

The online medium was also plagued by confusion about what to measure and who should do it (later chapters discuss competing metrics in greater detail). Should the effectiveness of the medium be measured by the number of unique viewers at a site, by clicks, by leads, or by acquisitions, among other measures? The technological ingenuity of the online channel had led to a proliferation of competing, clamoring metrics. Their Ginsu ingenuity notwithstanding, there was no consensus metric of ad performance-something that tends to thwart ad spending. By contrast, with TV advertising, as Terry Kawaja points out, “No one argues about the value of a Nielsen rating point.”

The online channel has also been beset by certain inherent vagaries. Users can come to a site from anywhere at any time. Moreover, with online media, the existence of the ad space, or the impression, happens on the spur of the moment. Only as a web page is being rendered for each new user does the ad space come into being. This creation of the ad space in the moment is the opposite of the static and enduring placement of a billboard.

Ad spending follows eyeballs. It’s just as true online. So welcome to our site, right? Yet, on Internet sites, those eyeballs are mystifyingly hard to keep in sight. Their attendance at a given site could be so brief, and they could leave with such suddenness. The event can be so fleeting, it is like trying to advertise to the dew as it’s evaporating.

During the early part of the previous decade, traditional ad agencies were still trying to match brands with the ever-increasing number of sites on the Internet. Since then, the terrain of interactive advertising has experienced tectonic shifts with the rise of paid-search advertising, advertising networks, and real-time bidding, along with the advent of social media and the proliferation of tablets and smartphones. But the gap between advertisers and online publishers remained, with the former trying to figure out how to target consumers with increasing accuracy and the latter at a loss about what to do with the sudden glut of unsold inventory-that is, the white space that may appear on your browser’s screen.2

As the number of sites online proliferated, and audiences fragmented into narrower and narrower niches, ad agencies found they lacked the relationships and resources to adroitly use the exponentially expanding resources of online publishers. Advertisers also had little experience allocating budgets across so many potential spaces. Furthermore, brands and agencies were suddenly expected to deliver proof of consumer engagement against a new set of online metrics and return-on-investment (ROI) benchmarks.

In addition, in its early days, ad serving on the Internet was fraught with technical difficulties as well as difficulties in determining optimization and fulfillment. Optimization here means getting the most impact from an ad or from some amount of spending for ad media. Fulfillment means the ad was shown to the potential consumer to whom the advertiser wanted to show it. Publishers in the new medium (including established major print publishers who were trying to become online moguls) often lacked the resources to fill their ad space. They simply didn’t have the ad sales staff and account management teams sufficiently knowledgeable in the new medium to help advertisers optimize their branding campaigns. Developing those relationships required a depth of management, expertise, and time that online publishers often lacked.

Deals Along the Internet Highway

A number of new, technologically savvy start-ups-new types of intermediaries-arose to make different aspects of ad serving work better for different types of clients, whether publishers or advertisers. Someone had to find a way to help both advertisers and publishers navigate the virtual topology of the Web world. These smaller, agile start-ups, staffed by people who had gained expertise in various subsegments of the markets, had experience making use of online data that neither advertisers nor publishers had developed in-house.

The great promise of interactive advertising, after all, was improved accuracy, targeting, effectiveness, and transparency. The amount of data suddenly available about consumer behavior and preferences promised to make the Nielsen TV rating system seem antiquated.

A range of new media partners entered the digital field to give guidance to both the brand-marketing and publishing sides. These intermediaries proposed to help advertisers optimize their placements and publishers sell their inventory, thereby bridging the online marketing gap.

To understand the opportunity for and the behavior of these intermediaries, it helps to take a closer look at your typical trip online.

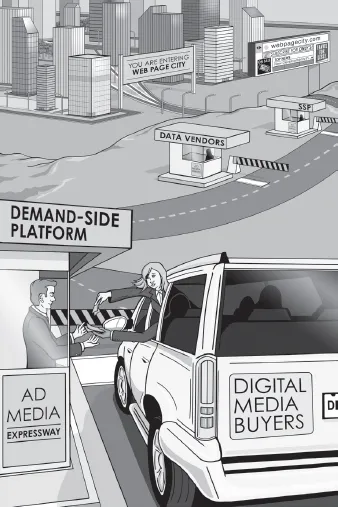

The Toll Road

Imagine each time you go online as a trip to a new destination. The address of the web page that you type into the browser address field sets your desired endpoint, and the instant you hit the Return key, you’re off. From your standpoint, the journey takes no longer than a few seconds. You take a sip of coffee, stare out the window, and, voilà!, your page is fully loaded and ready to read, almost as if by magic.

Inside the workings of the Internet, however, the route that brought you to, for example, Esquire’s homepage had many more stops than you might have realized. Let’s think of those stops as tollbooths. Standing between you looking at a blank browser screen and you arriving at your ultimate destination-the fully loaded web page you selected-are a horde of invisible toll collectors (the intermediaries), each of which collects a small cut of every advertising dollar so that you can visit the page you picked.

These tollbooth operators are those firms that play a role in ad serving, that help ensure that an ad gets to the right place on the page you intend to visit. Each receives a small piece of the money that was paid by the advertiser to place the ad on the appropriate page. All of the tollbooth operators, including, finally, the publisher of the web page, share in the revenues paid by the advertisers. In that way, they help keep the system running, and, as they do, small amounts of change (the tolls) add up to lots of dollars as thousands of viewers like you pass through their tollbooths.

How much do all those online tolls amount to? According to one widely accepted analysis,3 for every $5 an advertiser pays to place an ad online to be viewed by one thousand suitable consumers (called the cost per thousand, or CPM), the publisher on whose web pages the ads appear customarily gets less than $2. (We’ll come back in a later chapter to the enormous cost imposed by intermediaries, when we discuss alternatives to the toll road I have just described.)

Let’s imagine a site published by Hearst-say, www.esquire.com-as the end of the highway. That’s your objective. At the other end are the advertisers who, in a sense, are sponsoring your journey to that destination. Nowadays, an almost dizzyingly complex conglomeration of entities falls somewhere in the middle, between you and that destination.

Making up this complicated chain of intermediaries is some combination or all of the following: demand- and supply-side platforms, data optimizers and providers, ad exchanges, and ad networks, among others. And each of these many parties gets some sliver of the payment between the brand marketer and Hearst, as they enable you to get the content that you want.

To better understand the invisible mechanisms that deliver the Internet to your screen, let’s take a look at some of the principal service providers (“toll collectors”; see Figure 1-1).

The Toll Collectors

PUBLISHERS: If you have followed the news even casually over the last few years, it’s likely that you came across a story about publishing in crisis. (In fact, you probably saw that story on a screen instead of reading it on paper.) While rumors of newspapers’ last gasps have been greatly exaggerated, no one in any part of the media food chain would deny the industry upheaval that is reshaping the publishing world.

FIGURE 1-1 The highway and the toll collectors

For our purposes, a publisher is any content provider whose business model is providing information that is paid for by advertising. This includes portals like AOL, MSN, and Yahoo!; traditional news and special interest outlets such as nytimes.com, cnn.com, and esquire.com; search engines such as Google and Bing; and social media sites like Facebook and LinkedIn. These publishers may be “platform agnostic.” That is, they may deliver content by means of more than one medium. So, for example, Hearst provides Esquire’s content both in print and online.

AD NETWORKS: Now we’re getting into the heavily trafficked part of the toll road, where the most transactions take place. As Internet use expanded, most ad agencies did not have adequate media-buying resources to select and purchase ad spaces (impressions) across the multitude of websites suddenly sprouting up. Ad networks arose to meet this need for selective and efficient ad space allocation for presenting what are called display ads, which look like little billboards. They bought ad space in bulk from publishers, often at prices far below the full retail prices publishers asked for. Often, the impressions they bought were those the publishers were unable to sell-or unable to sell for good prices (known as remnant inventory). Then the ad networks resold their aggregate inventory across the Internet to advertisers and their ad agencies. (See Chapter 5 for a more detailed account of this moment in interactive advertising history.)

Some of the noteworthy ad networks are AOL’s Advertising.com, the Yahoo! Network, DoubleClick, Microsoft Media Network, and 24/7 Real Media. DoubleClick (which now operates a major online ad exchange) is owned by Google, providing the search giant with a perch at many locations along the toll road-as publisher, exchange, network, and advertiser. Smaller ad networks, such as Blogads, Deck Network, and Federated Media, help advertisers reach more specialized, niche audiences on sites that have limited ad inventory. By using these smaller networks, advertisers gain the benefit of knowing they are reaching a desirable, very selective segment of consumers.

AD EXCHANGES: The primary function of an exchange is to aggregate ad space (supply) from publishers and sell it via an auction, thereby matching the supply with the demand (the advertisers), theoretically with greater efficiency than if publishers and advertisers interacted one-to-one. Publishers might divide their inventory among, and advertisers may buy impressions from, multiple ad networks, operating as intermediaries. In contrast to all that dividing and allocating, the premise of an ad exchange, as with a stock exchange, is the consolidation of inventory so that these inventory-clearing, ad-serving transactions can take place with greater transparency and scale and at prices that work best for buyers and sellers.

This category of the toll landscape has seen a big consolidation over the past several years. The most prominent ad exchanges have been acquired by major online media conglomerates. Right Media was acquired by Yahoo! in April 2007 for $680 million. DoubleClick was purchased by Google in May 2007 for $3.1 billion. Microsoft bought ad exchange AdECN in August 2007 for an undisclosed amount.

DEMAND-SIDE PLATFORMS: As ...