![]()

PART 1

Thinking in Story

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Story Thinking

Our first stories come from our families, and they are intensely personal. My mother’s father died six months after I was born; yet through Mother’s stories, I feel as if knew my grandfather. He sold Kellogg’s cereals in the 1940s and 1950s. He was outgoing and loved practical jokes. I have a photo of him sitting like a general atop a pony so short his weight is not even on the animal. One of the stories Mother told me includes a joke he loved to tell. The punch line is at the heart of my book’s premise.

A man walks into a pet store and says, “I want a talking parrot.”

The clerk says, “Yes sir, I have two birds that talk. This large green parrot here is quite a talker.” He taps on the cage, and the bird says, “The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want.” “It knows the entire Bible by heart. This red one here is young but he’s learning.” He prompts, “Polly want a cracker.” The bird repeats, “Polly want a cracker.”

The man says, “I’ll take the younger one if you can teach me how to make it talk.”

“Sure I can teach you,” says the pet store owner. He sits down with the man and spends hours teaching him how to train the parrot. Then he puts the bird in the cage, takes the man’s money, and sends him home to start the training regimen.

After a week, the man comes back into the store very irritated.

“That bird you sold me doesn’t talk.”

“It doesn’t? Did you follow my instructions?” asks the clerk.

“Yep, to the letter,” replies the man.

“Well, maybe that bird is lonely. Tell you what. I’ll sell you this little mirror here and you put it in the cage. That bird will see its reflection and start talking right away.”

The man does as he was told. Three days later, he was back. “I’m thinking of asking for my money back. That bird won’t talk.”

The shop owner ponders a bit and says, “I’ll bet that bird is bored. He needs some toys. Here, take this bell. No charge. Put it in the bird’s cage. It’ll start talking once it has something to do.”

In a week, the man comes back angrier than ever. He storms in carrying a shoebox. “That bird you sold me died.” He opens the shoebox, and there is his poor little dead parrot. “I demand my money back.” The shop owner is horrified! “I’m so sorry, I don’t know what happened. But tell me … did the bird ever even try to talk?”

“Well,” says the man, “it did say one word, right before it died.”

“What did it say?” the clerk inquires. The man replies, “It said: ‘Fo-o-o-o-od.’ ”

Poor parrot, he was starving to death.

That parrot needed food the way we need meaningful stories. People are starving for meaningful stories, while we are surrounded by impersonal messages dressed in bells and whistles that are story-ish but no more effective than giving a mirror and bell to a starving parrot. People want to feel a human presence in your messages, to taste a trace of humanity that proves there is a “you” (individually or collectively) as sender. Learning how to tell personal stories teaches you how to deliver the sense of humanity in the messages you send.

Whether your goal is to tell brand stories, generate customer stories on social media, craft visual stories, tell stories that educate, interpret user stories for design, or build stories that explain complex concepts, the exercise of finding and telling your own stories trains your brain to think in story.

Story thinking maps the emotional, cognitive, and spiritual world of feelings. For humans, feelings come first. We destroy facts we don’t like and elevate lies that feel good. We’ve tried to control this tendency by teaching ourselves to make more rational, unemotional, and objective decisions. It’s worked pretty well, but if all you have ever been taught is to make unemotional, objective decisions, your capacity to stir emotions, see stories, and understand the logic of emotions may be underdeveloped or nonexistent. This book gives you new skills in story thinking that will complement your skills in fact thinking. Facts matter, but feelings interpret what your facts mean to your audience.

How to S.E.E. Stories

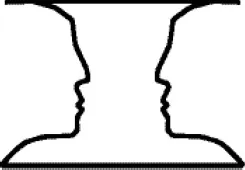

Any significant emotional event (s.e.e.) can be a story. Similar to shifting between yin and yang, right brain and left brain, or art and science, the following image demonstrates how you can’t see two frames of reference at the exact same time … You can go back and forth as fast as you like, but in the instant you see the people the vase disappears and vice versa. It is the same when we s.e.e. stories. We may have to allow the data to become ambiguous for a second in order to discover a story that provides new context and enough meaning to change how people interpret the data.

Once you learn to flip back and forth between objective thinking (the vase) and story thinking (the people), you can present the right answers in a way that not only is factually correct but feels right too. If the right answers were enough, everyone who needs to lose weight would only ever have to read one diet book. Behavior change requires more than knowing what to do; we have to feel like doing it.

Story thinking may feel a little scary to the average business mind because it calls for us to temporarily lay objective thinking to the side and look at the stories, metaphors, analogies, and intuitions that explain emotional responses. Much like the vase/people picture, we can look at one and then the other, granting them equal time and then blending the wisdom of both. Compared to facts, stories look ambiguous and inconsistent. We must seek to understand emotions by learning to speak the ambiguous, variable, and unsteady language of emotions—the language of story.

The emotional payoff of a powerful story warrants the act of letting go of critical thinking long enough to find a story. Do we need expensive quantitative data analysis to find ideas more easily discovered by feeling our way through stories? Recently, a quantitative analysis of data from employee name badges embedded with microphones, location sensors, and accelerometers revealed that productivity goes up and turnover goes down when you replace the fancy coffee machine reserved for senior executives with a shared space encouraging unstructured, 15-minute coffee breaks for everyone. We need only to seek stories about inclusion and exclusion to find ways to improve engagement and save our research money for experiments.

Story thinking happens naturally as you gather and tell stories that simulate the kind of life experiences that people consider to be meaningful. If something feels meaningful, it is meaningful because of the story we tell ourselves about it. Stories track patterns of interpretation that people, institutions, and cultures weave around events. Stories hover over the facts and draw lines of connection or disconnection—good, bad, relevant, or irrelevant—to create personally interpreted meaning.

What’s Important and Why

Every culture is based on stories and metaphors that aggregate around that culture’s preferential answers to universal but ambiguous human dilemmas like how to manage time, authority, safety, money, ethics, and whatever else is important. If it is important to the culture, you will find a story that tells you what is important and why. In Russia, I was told how real estate contracts were simply voided when a better offer came in because “Russians play with the rules rather than by the rules.” As an American, I have my own biases, but this story clearly told me what to expect and how to act.

Lots of wonderful things become possible with story thinking. When you know what you should do, but don’t feel like doing it, calling up the right story can tip the balance in your favor. When I teach storytelling to executives, some on the edge of burnout, they report a surge of energy and appreciation after sharing stories of why they chose their occupation.

Writing about an unexpected text message from a mentor who typed, “I totally adore you,” magically changes how I feel. Later, when I shared this boost with my friend at lunch, it changed how he felt too. He smiled as I shifted from feeling stressed to basking in adoration.

Notice what happens to your physiological state, attention, emotions, and behavior when you remember your first love. How old were you? What hairstyle and clothing were you wearing? Picture the attention you gave every interaction, potential interaction, and fantasized interaction. Stay there until you feel a ghost of the feelings you felt then. Have you smiled yet? Do you feel a slight urge to action? Perhaps you want to discover where your long lost love is now.

Now steel yourself for a less pleasant trip. Go back to high school and pull up a memory of an embarrassing rejection. Any public humiliation will do—just choose one. If you are like most people, high school was full of them. Give that embarrassing memory all your attention. Remember the names, see the places, and reenact the scenes. Now notice the ghosts of the feelings you felt then as they reignite. You may feel a tug toward actions that prevent this kind of experience. This experiment demonstrates how attention—in this case, attending to a memory—alters your current reality by changing how you feel.

The key to story thinking is to learn which stories stimulate your own feelings first. Then find the stories that also stimulate the feelings of others. The skills you develop by starting from the inside will help you learn the way stories create the feelings that motivate us to action.

Story Thinking Is Not the Opposite of Objective Thinking

Learning to think in story does not erode your ability to think in objective terms. You can still conduct a cost/benefit ratio analysis with the best of them. If you naturally use objective tools such as root cause analysis or statistics to identify “right” and “wrong,” it may be uncomfortable to flip into subjective mode. It is important to remember that we don’t abandon objective logic and measurable outcomes when we think in stories. We complement objective facts with the kind of story thinking that tracks emotional and perceptual patterns in others and ourselves. Story thinking explores the fact that people can make the right decision for the wrong reasons and opens our eyes to see how wrong can be good (watch much reality TV?) and right can be bad (patenting a cure during a pandemic) without forcing an oversimplified resolution or averaging extremes into zero.

Some gifted individuals seamlessly process objective and subjective factors as easily as a child prodigy plays the piano. The rest of us lean to one side or the other. Western education tends to produce more objective thinkers. The style of right-brain thinking, artistic interpretation, and the hidden world of yin are so similar to story thinking they can sometimes feel interchangeable. In other words, if you are already a master of left-brain, science-oriented, yang energy, then story thinking is your fast track to find more innovative, human-centered ideas and make better emotional connections.

Relax Your Internal Critic

Your internal critic might seek to discredit story thinking as too subjective, irrational, or corny. Stories are a hot topic right now, but the process of finding and telling stories is old fashioned—prehistoric, in fact. Objective thinking tempts us to update this process with technology, automation, or measures. Beware: you may just destroy that which you seek to understand.

I’m not a fan of techniques that try to turn the subjective nature of stories into modules, recipes, or tactics. I hear people say stories always have a beginning, middle, and end. Hell, what doesn’t have a beginning, middle, and end? Likewise, you can have a plot, characters, themes, and crisis and still not have a good story. Whatever interaction simulates a visceral, experiential sense of meaning—to the satisfaction of the listener and the teller—is a story.

Stories don’t just map the way humans thought before we discovered science and technology. Stories represent the way the human brain still thinks. The first step is to suspend objective thinking and find the source code of human emotion: experiences. Stories are encoded by the social and emotional brain, the limbic system, the amygdala, and the other core parts of the brain that trust the five senses more than symbols such as numbers or an alphabet. Here, numbers and language do not represent physical reality as well as memory and images do. These parts of the brain treat experience as the best teacher. Stories are only one step removed because stories are simulated experiences.

Stories do not obey traditional rules of logic, and they can change your interpretation of what is meaningful and important in the wink of an eye. It’s disconcerting at first, but once you get used to it, you discover this is the magic of story thinking.

An old farmer patiently spent part of each afternoon talking with a nosy neighbor, who visited him about the same time every day. One afternoon during his daily visit, the neighbor suddenly exclaimed, “Did you buy a new horse? Yesterday you only had one horse, now I see two.”

The farmer told the neighbor how this horse, unmarked and apparently without an owner, wandered into his barn. He explained that he had asked everyone he knew, and since no one owned the horse, he decided he would care for it until they found its owner.

The neighbor said, “You are such a lucky man. Yesterday you had only one horse and today you have two.” The farmer said, “Perhaps, we shall see.”

The next day, the farmer’s son tried to ride the new horse. He fell and broke his leg. That afternoon the neighbor said, “You are an unlucky man. Your son now can’t help you in the fields.” The farmer said, “Perhaps, we shall see.”

The third day, the army came through the village looking for young men to conscript to fight. The farmer’s son was not taken because he had a broken leg. The neighbor again said, “You are a lucky man,” and again the farmer said, “Perhaps, we shall see.”

Think about the time wasted arguing about what is or isn’t true, when it all depends on the stories we tell ourselves. The farmer was unlucky and lucky, depending on the story. Both are true, depending on where you are in the story. Story thinking adapts decisions and implementation strategies to suit changing points of view rather than forcing all ambiguities to resolve into the false clarity of the lowest common denominator. We know everything will change tomorrow anyway, so we may as well lean on the things that don’t change—meaning and universal truths. Stories that are emotionally stimulating relay truths that were true before you and I were born and will remain true long after we die.

The Western world has spent a lot of time and energy learning how to exclude emotions from decision making, but decisions that ignore emotions are easily ignored in return. Story thinking doesn’t bring emotions back to decision making, but it gives us access to the emotions that have been there since the beginning of human history.

Thinking in stories can feel dangerous or unstable, but as a psychiatrist friend of mine put it, a blind man who could suddenly see would not poke his eyes out just because some of the things he saw were terrible. Stories simply reveal the patterns of emotional reasoning where they lay so you can see the best possible route to where you want to go.

This book is designed to help you lay the groundwork for using stories as credible tools. Understand that allowing the emotions back in...