![]()

Chapter 1

The Palmyrene

Palmyra was more than an urban area enclosed by a city wall. It also encompassed an extensive hinterland composed by a varied mosaic of smaller settlements, farmsteads, monasteries, forts, and residences of the aristocratic élite and the members of the ruling dynasty. The political, economic, and cultural relation between these and Palmyra must have been vibrant, influencing the history of the site to an extent that is very difficult to investigate in depth with the data at hand. In fact, compared with the evidence brought to light in Palmyra itself, the archaeology of the Palmyrene is still at its infancy. A work devoted to gather the Late Antique and Early Islamic evidence from the Palmyrene, with special focus on the diffused phenomenon of the Umayyad aristocratic residences, has been conducted recently (Genequand 2012). Yet, a brief overview of the archaeology of this region remains indispensable in order to set the city in context.

Palmyra’s hinterland

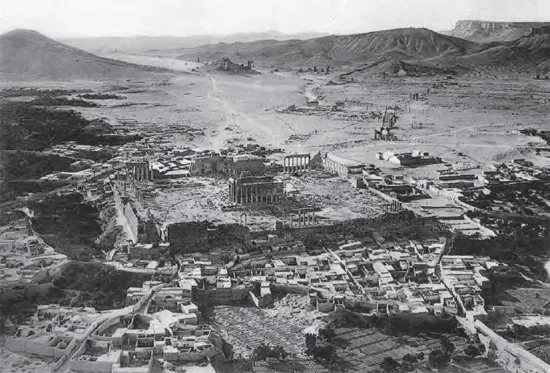

The geography of the regio Palmyrena is marked by the presence of two groups of mountains, the Palmyrenides, originating to the west from the anti-Lebanon mountains. At the point where Palmyra is situated, the two groups counterpose and slope gently, thus creating a more easily accessible pass. Each group of the Palmyrenides includes a multitude of different mountain chains divided by steep valleys (Genequand 2012, 9–11). Separating the northern from the southern Palmyrenides is al-Daww, which is an oblong 8000m2 plain, stretching from the region of Ḥuwwārīn for some 180km. The water flowing into this plain from the surrounding mountains infiltrates rapidly into the soil, feeding the springs of the region (Sanlaville and Traboulsi 1996, 29–30). At the deepest point of the Palmyrene depression (364m a.s.l.), to the southeast of the city, is a vast, 330km2 salt flat, Ṣabkhat al-Mūḥ, which has benefited the local economy since antiquity (Teixidor 1984, 78–80). No major natural barriers occur to the east of Palmyra until the Euphrates River, which is 240km to the east, as the crow flies (Fig. 1). A plan of the city, with key places and buildings referred to in text, is provided in Figure 2. Figures 3 and 4 show the state of the ruins in 1932 (Autumn) and 1931 respectively.

The administrative limits of the territory under the jurisdiction of Palmyra in Roman times were influenced by the rough geography of the region. Boundary markers help draw two exact limits. One was set at Khirbat al-Bil ʿās, to the northwest. Here, two inscriptions commemorate the re-establishment of a pre-existing boundary under Trajan and Antoninus; this had been originally set by Creticus Silanus in 11–17 (Schlumberger 1939a, 61–3). At this point, the regio Palmyrena may have adjoined either the territory under the jurisdiction of Antioch (Seyrig 1959, 190, n. 2), or that of Apamea (Balty and Balty 1977, 118). A third boundary marker found at Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Gharbī ‘inter Hadrianos Palmyrenos et Hemesenos’ set a further limit to the southwest (Schlumberger 1939a, 63–4). The Palmyrenides might have worked as convenient natural boundaries to the north and south of the plain of al-Daww. To the east and southwest of the city no boundary markers are known, but it is very likely that the territory of Palmyra extended to the Euphrates River (Gawlikowski 1983d, 58; recently, Smith 2013, 4). So defined, the territory of Palmyra in Roman times was situated in the province of Syria and, with Septimius Severus, Syria Phoenice.

Our knowledge of the territory of Palmyra in Late Antiquity is more blurred than that of the Roman period, as no boundary markers are known for this period. It is likely that the mountainous geography of the region helped maintain the administrative boundaries already existing, with the exception, perhaps, of the area comprised between the city and the river Euphrates; this might have experienced a re-shuffle after the fall of Zenobia in the late 3rd century and the following period of political instability of the local nomadic component. At the time, Palmyra and its surroundings were situated in the province of Phoenicia Libanensis (Proc., Aed., 6.1.1; 2.11.10; Hier., Synec., 717.1–8; Georg. Cypr., Descr. Orb. Rom., 984–96; ACO 2.5.46). Similar uncertainty shrouds our knowledge of the administrative boundaries of the Palmyrene territory in the Early Islamic period, as epigraphic evidence on this regard is non-existent. The general political geography of the time, however, is known. After the Islamic takeover, the provincial system at the base of the Byzantine administration underwent significant changes. During the caliphate of ‘Umar b. al-Khaṭṭāb (634–644), the province of al-Shām was created. This was split into four administrative and military districts called ajnād (sing. jund); Palmyra, and perhaps the territory formerly under its jurisdiction, became part of the jund of Homs, ancient Emesa (al-Muqaddasī, Aḥsan, 158–9).

Figure 1. Main sites mentioned in the text (image: author).

A city ‘built in a neighbourless region by men of former times’? Remarks on the regional road system, and evidence for travel and commerce

The liminal location of Palmyra and the Palmyrene as well as their remoteness are often emphasised in ancient written sources. Malalas (Chr., 17.2) stresses the city’s frontier location, while Theophanes (Chr., 1.174) reports that Palmyra is situated ‘on the inner limes’ (εἸζ τò λιμιτòν τò ἐσώτερον). The passage of Theophanes has been the cause of confusion among modern historians and archaeologists. Starting from the influential work of Mouterde and Poidebard at the beginning of the last century, the word ἐσώτερον, usually rendered as ‘inner’ in translation, has often been used by scholars to support the existence of a frontier system consisting of two lines of defence: an ‘inner’, located around Qinnasrīn (Chalcis) and an ‘outer’ one running from Sūriyya (Sura) to Damascus via Palmyra (Mouterde and Poidebard 1945; however, this theory was discredited a long time ago, Liebeschuetz 1977, 487–8; more recently, Tate 1996; for an extended bibliography see, Konrad 1999, 392, n. 2). The translation of ἐσώτερον as ‘inner’ cannot be applied to our case study since if one has to follow Mouterde and Poidebard’s model, Palmyra would be located on the ‘outer’ line. It is, therefore, likely that by using this term, Theophanes wanted simply to stress Palmyra’s remote location at the fringe of the empire (Liebeschuetz 1977, 488). The idea of Palmyra as a settlement in an undefined, isolated, and faraway land had certainly developed earlier. In his De Aedificiis, Procopius (Aed., 2.11.10) had already described the city as ‘built in a neighbourless region by men of former times’ (ἐν χώρα μἐν πεποιημένη τοĩζ πάλαι ἀνθρώποιζ ἀγείτονι, tr. Dewing 1961, 177), and had taken the Justinianic renovations of the settlement as proof of the ability of the Imperial authority to reach even the most remote location in the empire with its tentacles (Proc., Aed., 5.1.1). The perception of Palmyra that emerges from an attentive reading of the written sources is, therefore, that of a city standing in isolation in the Syrian steppe.

Figure 2. Plan of Palmyra. 1. Houses of Achilles and Cassiopea; 2. Sanctuary of Bel, 3. Great Colonnade; 4. Suburban Market; 5. Byzantine Cemetery; 6. Buildings encroaching Section A of the Great Colonnade; 7. Church; 8. Baths of Diocletian; 9. Theatre; 10. Annexe of the Agora; 11. Agora; 12. Sanctuary of Arsū; 13. Congregational Mosque; 14. Church; 15. Tetrapylon; 16. Sanctuary of Baalshamīn; 17. Umayyad Sūq; 18. Church II; 19. Church III; 20. Church IV; 21. House F; 22. Church I; 23. Bellerophon Hall; 24. Church; 25. Peristyle Building; 26. Transverse Colonnade; 27. Camp of Diocletian; 28. Sanctuary of Allāth; 29. Building [Q281]; 30. Efqa spring; 31. Western Acqueduct (redrawn after Schnädelbach 2010).

Figure 3. Aerial photograph of Palmyra taken looking southwest (Poidebard 1934, pl. 67).

It is legitimate to ask, however, whether this idea reflects the stereotypical perception that the above writers had of the settlements along the eastern frontier, rather than reality. As a matter of fact, information from the Tabula Peutingeriana, complemented with the archaeological record, suggests that the city did not sit in remote isolation, but was fully integrated in the road network of the time. The Tabula Peutingeriana (seg. 10–11, Fig. 5) shows two roads departing from the city. One heads northeast, circumventing the Jabal Abū Rujmayn to the east, to reach Sura (Sūriyya). It would have passed via Harae (Arāk), Oresa/Oruba (al-Ṭayyiba), Cholle (al-Khulla), and Sergiopolis (al-Ruṣāfa – Risapa in the Tabula Peutingeriana). The second would have led to Apamea via Centum Putea, Occaraba (ʿUqayribāt), and Theleda (Tall ʿadā). The document also reveals a third road, starting not far from Palmyra to reach Damascus via Heliarama (Qaṣr al-Ḥayr al-Gharbī), Nezala (al-Qaryatayn), Danova, Cehere, (Qāra), Casama, (al-Nabk), and ad Medera.

Other major roads are not documented in the Tabula, but are known from aerial and ground surveys that were conducted mainly at the beginning of the last century. A second connection to Damascus, known in French literature as the ‘route des khāns’, followed the eastern slopes of Jabal al-Niqniqiyya, Jabal al-Ruwāq, and Jabal Haymūr. Its course was policed by a number of military installations, on which more will be said below. The section of this road from Thelseai (al-Ḍumayr) to Palmyra and the detour to Avatha (al-Bakhrāʾ) is known on Tetrarchic milestones with the name of Strata Diocletiana (Bauzou 1993; 2000). Another major track connected Palmyra with Emesa (Homs), passing through the plain of al-Daww. Its existence is confirmed by numerous Diocletianic milestones found along its course (see below, p. 21). The incorrect statement of Palladius (Dial. John Chris., 20.35–8), who refers to Palmyra as a city situated ‘eight milestones from Emesa’, suggests that the road was still functional in the early 5th century. In addition, the body of St Anastasius might have travelled in this road on his way to Jerusalem via Arados (Arwād) in 630 ( Anas. Per., 1.102–4). A connection existed also between Palmyra and Acadama (Qudaym) – the site of a garrison of Equites Sagittarii (Not. Dig., Or., 33.12, 21) via Jabal Abū Rujmayn. From there, it was possible to reach Seriane (Ithriyya) to the northwest, or Oresa/Oruba (al-Ṭayyiba) to the east (Mouterde and Poidebard 1945, 109–15; Fig. 6).

Figure 4. The state of the ruins of Palmyra in 1931, Bureau Topographique des Troupes Françaises du Levant (detail; scale 1:10,000. Courtesy of the National Library of Scotland).

Unlike the relative abundance of pieces of evidence for Late Antiquity, there are no written or epigraphic sources to shed light on the status of the road network in the Palmyrene in the Early Islamic period. It is now believed that the new political geography of the Umayyad period encouraged the flourishing of trade routes, marking in most cases the end of an insular economy and the reinforcement of long-distance trade networks (Bessard 2013). Due to its location, Palmyra might have benefited from such traffic. In all likelihood, the pre-existing road system would have been of functional use in the Early Islamic period. In addition, the major track leading to Iraq would have been re-established (or reinforced), assuring trade connections with regions on the left bank of the Euphrates.

Figure 5. Tabula Peutingeriana, seg. 10–11 (courtesy of the Austrian National Library).

Figure 6. The road network of the Palmyrene (Mouterde and Poidebard 1945, pl. 1).

Blurred evidence of travels through the Palmyrene in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic period exist. The only inscription recording the presence of Palmyrenes outside Palmyra is a funerary graffito found in the Tombs of the Prophets at Jerusalem, which mentions a certain ‘Anamos, clibanarius teriius (?) of Palmyra’ (Ἂναμοζ κλιβανάρι(ο)ζ [τρίτοζ?] Παλμύραζ – Clermont-Ganneau 1899, 364–7). The soldier (or his body) reached his final resting place passing by Damascus either via Emesa or via the more direct ‘route des khāns’. Written sources are only slightly more informative. At the end of the 4th–beginning of the 5th century, Alexander the Akoimētes and his followers are recorded to have stopped for three years in a fort, either at Oresa/Oruba (al-Ṭayyiba) or Sergiopolis (al-Ruṣāfa), and then to have moved southward to Palmyra, very likely following the via militaris described above (Alex. Akoim., 35; Gatier 1995, 452). Finally, the monks translating the remains of St Anastasius from Dastagerd to Jerusalem in 630, travelled through Palmyra to Arados (Arwād) presumably through Emesa. From there, he and his companions reached Tyre by sea ( Anas. Per., 1.102–4).

In the Early Islamic period, a number of sources mention the journey of Sulaymān b. Hishām with Ibrāhīm b. al-Walīd from Palmyra to the residence of Marwān b. Muḥammad (r. 744–50), near Ḥarrān, to pledge allegiance to the caliph (al-Ṭabarī, Tāʾrīkh, 9.1892; Ibn ʿAsākir, Tāʾrīkh, 15.83). However, they provide little clue on the route undertaken by the traveller. Similarly, Theophanes (Chr., 1.422) recounts that after being defeated by Marwān, Sulaymān ‘escaped first to Palmyra then to Persia’ (tr. Ηoyland 2011, 258). Analogous generic accounts are not out of the ordinary in Early Islamic written sources. In accounting the life of Dhuʾāla b. al-Aṣbagh b. Dhuʾāla al-Kalbī, Ibn ʿAsākir (Tāʾrīkh, 17.326) reports that his three sons, Dhuʾāla, Ḥamza and Furāfiṣa threw off allegiance to the caliph and moved from Palmyra to Homs. It is reasonable to assume that the pre-existing road through al-Daww connecting Palmyra to Homs was used by the travellers. Only sporadically, ancient sources provide detailed clues. In accounting the siege...