- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

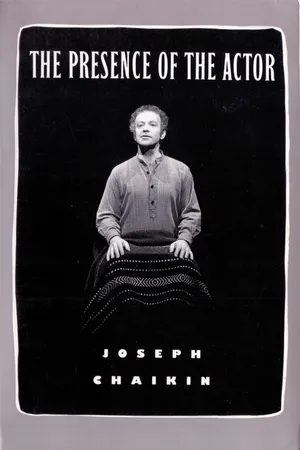

The Presence of the Actor

About this book

Chaikin, who directed the celebrated Open Theater in the '60s, kindled an emphasis on communal playmaking whose impact is still evident today. This conversational review of his efforts details his methods and reveals the struggles involved in the creation of some of the most exciting theatre of our time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Presence of the Actor by Joseph Chaikin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Acting & Auditioning. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

There is another world, and it is in this one.

—PAUL ELUARD

Notes on Content

Most of the people I know who are seriously interested in the theater don’t really like it very much. There is the situation being played out on the stage (the play), and there is the situation of actually being in the theater—the relationship between the actors and the audience. It is this living situation that is unique to the theater, and the impulses of a new and more open theater want to manifest it.

When I go uptown and see a Broadway play, I go to see primarily the ushers, the box office, and the environment of the physical theater. This situation has become more present than the situation being played out on the stage.

The joy in theater comes through discovery and the capacity to discover. What limits the discoveries a person can make is the idea or image he may come to have of himself. The image can come about through his investment in his own reputation, through an involvement with approval and disapproval, or through feelings of nostalgia stemming from his desire to repeat his first discoveries. In any case, when his image becomes fixed, it limits him from going on to further discoveries.

Acting is a demonstration of the self with or without a disguise. Because we live on a level drastically reduced from what we can imagine, acting promises to represent a dynamic expression of the intense life. It is a way of making testimony to what we have witnessed—a declaration of what we know and what we can imagine. One actor in his acting expresses himself and touches nothing outside of himself. Another actor, in expressing himself, touches zones of being which can potentially be recognized by anyone.

There are actors whose main interest in going into the theater is to seek a kind of flattery. This kind of seeking makes the actor, and, through him, the theater itself, vulnerable to the sensibility of the market place. Traditional acting in America has become a blend of that same kind of synthetic “feeling” and sentimentality which characterizes the Fourth of July parade, Muzak, church services, and political campaigns. Traditionally, the actor summons his sadness, anger, or enthusiasm and pumps at it to sustain an involvement with himself which passes for concern with his material. The eyes of this actor are always secretly looking into his own head. He’s like a singer being moved by his own voice.

My intention is to make images into theater events, beginning simply with those which have meaning for myself and my collaborators; and at the same time renouncing the theater of critics, box office, real estate, and the conditioned public.

The critic digests the experience and hands it to the spectator to confirm his own conclusion. The spectator, conditioned to be told what to see, sees what he is told, or corrects the critic, but in any case sees in relation to the response of the critic. Unfortunately, none of this has to do with the real work of the artist.

Situations

Most of the time when we learn about acting, it is in relation to situations. In professional acting schools we play out situations of triangle love affairs; of businessmen and their families going bankrupt; of aging actresses; of people locked in boredom, etc. In our own lives all of us are involved in situations, and we often identify ourselves to ourselves in terms of the situations we find ourselves in. If you move to a strange town where you have no particular interest in what is going on, it isn’t long before you become involved with the currents and stakes of those around you. The same is true of other kinds of new situations, new jobs, new friends. Situations enclose us like caves and become the walls and ceilings of our concerns.

There is no one direction in the theater today. The Living Theater, Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theater, the Berliner Ensemble, Jerzy Grotowski’s Polish Lab Theatre, and Joan Littlewood’s theater are as different from one another as it is possible to be. They differ widely in aesthetic values and, drastically, in the relationships of their work to the lives of their creators.

The law will never make men free; it is the men who have got to make the law free. They are the lovers of law and order who observe the law when the government breaks it.

—THOREAU

Assumptions on Acting

The context of performers—that world which the play embraces—is different from one play to another. Each writer posits another level, and even within the works of one writer these worlds may be quite different. An actor, no matter how he is prepared in one realm, may be quite unprepared when he approaches another. He must enter into each realm with no previous knowledge in order to discover it. An actor prepared to play in Shaw’s Saint Joan is hardly closer to playing in Brecht’s Saint Joan of the Stockyards than one not prepared for Shaw’s work. Each play requires a whole new start. An actor can’t proceed without empathy with the writer’s struggle nor without an awareness of the struggle of the character he is to play.

Technique is a means to free the artist. The technique needed for the playing of a family comedy is of no use to the actor whose interests lie in performing in political theater or theater of dreams. An actor’s tool is himself, but his use of himself is informed by all the things which inform his mind and body—his observations, his struggles, his nightmares, his prison, his patterns—himself as a citizen of his times and his society.

There are two ways for an actor to regard his own accomplishments: (1) he can compare present accomplishments with those of the past; and (2) he can compare himself to others.

An actor should strive to be alive to all that he can imagine to be possible. Such an actor is generated by an impulse toward an inner unity, as well as by the most intimate contacts he makes outside himself. When we as actors are performing, we as persons are also present and the performance is a testimony of ourselves. Each role, each work, each performance changes us as persons. The actor doesn’t start out with answers about living—but with wordless questions about experience. Later, as the actor advances in the process of work, the person is transformed. Through the working process, which he himself guides, the actor recreates himself.

Nothing less.

By this I don’t mean that there is no difference between a stage performance and living. I mean that they are absolutely joined. The actor draws from the same source as the person who is the actor.

In former times acting simply meant putting on a disguise. When you took off the disguise, there was the old face under it. Now it’s clear that the wearing of the disguise changes the person. As he takes the disguise off, his face is changed from having worn it. The stage performance informs the life performance and is informed by it.

MORE ASSUMPTIONS

Our training has been to be able to have access to the popular version of our sadness, hurt, anger, and pleasure. That’s why our training has been so limited.

Shock: We live in a constant state of astonishment which we ward off by screening out so much of what bombards us . . . and focusing on a negotiable position. An actor must in some sense be in contact with his own sense of astonishment.

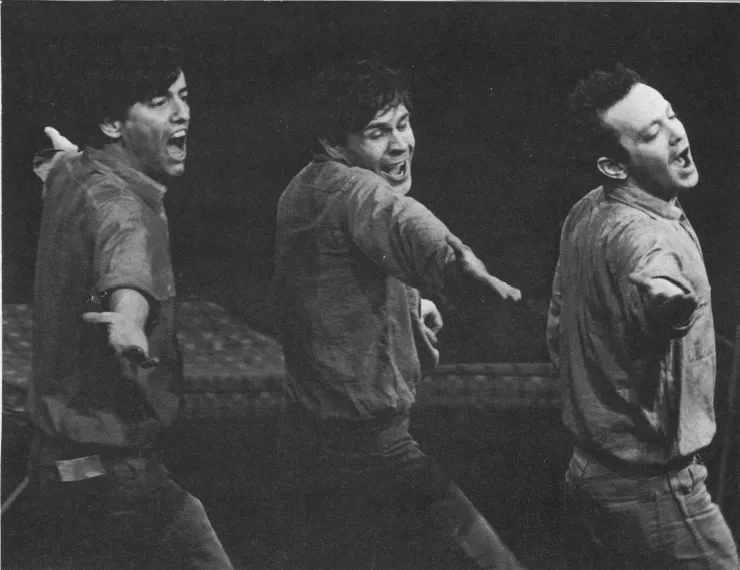

Keep Tightly Closed in a Cool Dry Place (1965): LEFT TO RIGHT, Jim Barbosa, Ron Faber, Joseph Chaikin

“Reality” is not a fixed state.

The word “reality” comes from the Latin word res, which means “that which we can fathom.”

Questions on the Actor’s Impulse

From where is the impulse drawn?

When I make a motion with my arm, from where do I draw the energy in order to perform the motion?

If I go across the room to open the window, it’s my interest in the outside that releases the energy for the walk across the room. The “impulse,” in this case, is that which starts a motion-toward.

When an actor releases vocal sound in an exercise, where does he draw energy from? From the interest to do what the teacher told him? From the interest to do what is “good for” him?

When an actor responds to an imaginary stimulus, he himself chooses and shapes that stimulus. He has the potential for a deep contact with that stimulus, since it is privately chosen. This contact brings up energy for the actor’s use. On one level or another he is given energy by his inner promptings, associations, that part of his life which is already lived.

From what part of himself is he drawing these associations as he performs? Does he draw from information and ideas of the character, the audience, and his self-image? Does he draw from a “body memory”? Does he draw his impulse from a liberated consciousness or from the same consciousness which he believes to be necessary for his daily personal safety? Does he draw from a common human source or from the contemporary bourgeois ego?

THE ACTOR MAKES A REPORT

From where in himself does the actor make his report?

Imagine a burning house:

1.You live in the house that is on fire. Even your clothes are charred as you run from the burning house.

2.You are the neighbor whose house might also have caught fire.

3.You are a passer-by who witnessed the fire by seeing someone who ran from a building while his clothes were still burning.

4.You are a journalist sent to gather information on the house which is burning.

5.You are listening to a report on the radio, which is an account given by the journalist who covered the story of the burning house.

The actor is able to approach in himself a cosmic dread as large as his life. He is able to go from this dread to a joy so sweet that it is without limit. What the actor must not do is to cling to any internal condition as being more or less human . . . more or less theatrical . . . more or less appealing. Only then will the actor have direct access to the life that moves in him, which is as free as his breathing. And like his breathing, he doesn’t cause it to happen. He doesn’t contain it, and it doesn’t contain him. The “act” is one of balancing between control and surrender.

During performance the actor experiences a dialectic between restraint and abandon; between the impulse and the form which expresses it; between the act and the way it is perceived by the audience. The a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- A Note on the New Edition

- Foreword

- Contents

- Chapter I

- Chapter II

- Chapter III

- Chapter IV

- Chapter V

- Chapter VI

- Chapter VII

- Chapter VIII

- Chapter IX

- Chapter X

- Chapter XI

- Chapter XII

- Chapter XIII

- Chapter XIV

- About the Author