- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

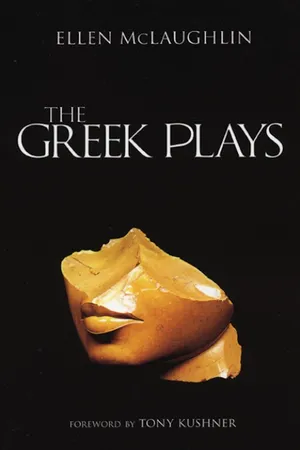

The Greek Plays

About this book

From The Persians

"Defeat is impossible

Defeat is unthinkable

We have always been the favorites of fate.

Fortune has cupped us

In her golden palms.

It has only been a matter

Of choosing our desire. Which fruit

To pick from the nodding tree."

This chilling passage is from Ellen McLaughlin’s new adaptation of The Persians by Aeschylus, the earliest surviving play in Western literature, an elegy for a fallen civi-lization and a warning to its new conqueror. As Margo Jefferson wrote in the New York Times, "The play is a true classic: we see the present and the future right there, inside the past. And when writers give us a ‘new version’ (a translation or adaptation) of a classic, they both serve and use it. They serve the playwright’s gifts by refusing to simplify. But they can’t just imitate. Every age has its own rhythms and drives. The classic must make us feel the new acutely. Ellen McLaughlin serves and uses The Persians with true power and grace."

Also included in this volume: Iphigenia and Other Daughters (from Euripides and Sophocles); The Trojan Women (Euripides); Helen (Euripides); and Lysistrata (Aristophanes), all powerfully realized and as relevant today as when they were first performed.

Ellen McLaughlin’s plays include Days and Nights Within, A Narrow Bed, Infinity’s House and Tongue of a Bird, which have been widely produced. She is a past finalist for the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize and was the co-winner of the Great American Play Contest. Also an accomplished actor, Ms. McLaughlin is most known for having originated the part of the Angel in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, appearing in every U.S. production through its Broadway run.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Iphigenia and Other Daughters

- The Trojan Women

- Helen

- Lysistrata

- The Persians

- Oedipus

- Copyright Page