- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

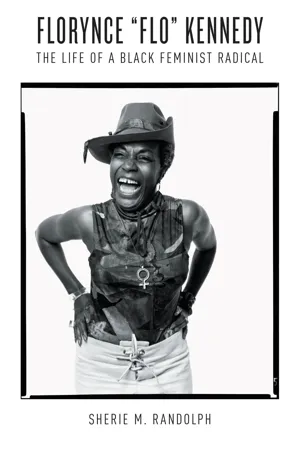

Often photographed in a cowboy hat with her middle finger held defiantly in the air, Florynce “Flo” Kennedy (1916–2000) left a vibrant legacy as a leader of the Black Power and feminist movements. In the first biography of Kennedy, Sherie M. Randolph traces the life and political influence of this strikingly bold and controversial radical activist. Rather than simply reacting to the predominantly white feminist movement, Kennedy brought the lessons of Black Power to white feminism and built bridges in the struggles against racism and sexism. Randolph narrates Kennedy’s progressive upbringing, her pathbreaking graduation from Columbia Law School, and her long career as a media-savvy activist, showing how Kennedy rose to founding roles in organizations such as the National Black Feminist Organization and the National Organization for Women, allying herself with both white and black activists such as Adam Clayton Powell, H. Rap Brown, Betty Friedan, and Shirley Chisholm.

Making use of an extensive and previously uncollected archive, Randolph demonstrates profound connections within the histories of the new left, civil rights, Black Power, and feminism, showing that black feminism was pivotal in shaping postwar U.S. liberation movements.

Making use of an extensive and previously uncollected archive, Randolph demonstrates profound connections within the histories of the new left, civil rights, Black Power, and feminism, showing that black feminism was pivotal in shaping postwar U.S. liberation movements.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Florynce "Flo" Kennedy by Sherie M. Randolph in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Political in the Sense That We Never Took Any Shit

FAMILY AND THE ROOTS OF BLACK FEMINIST RADICALISM, 1916–1942

Florynce Kennedy was a small child when a group of armed white men paid a visit to her family’s home in Kansas City, Missouri, around 1919. The American Neighbors Delegation, as Flo later dubbed it mockingly, told her mother, Zella, that “we weren’t wanted and that we’d better leave.” They “indicated that they didn’t want to have to hurt anybody,” but if the Kennedy family did not move from the home they owned, the group of men would have no other choice but to force them out. The neighborhood was for whites only, and black families were not welcome.1

Although Flo was too young to remember her mother’s exact words to the fifteen or so men on their front steps, she concluded that “whatever she said, or did, and however she acted must have been just right because they went away.” Years later, when Flo was a grown woman in her thirties, she asked her father about the legendary confrontation between the Kennedys and the armed white mob. For the first time, Flo heard of her mother’s heroism in talking the white men off their property. Flo tried to imagine how the woman she knew as even-tempered could have convinced the men to leave. Finally, she decided that her mother must have displayed just the right amount of strength.2

In Flo’s adult memory, her father, Wiley Kennedy, was more combative and more likely to challenge whites. He confirmed Flo’s impression of him when he said that if he had been the one to confront the white men that Sunday, he would not have kept his temper in check, and the exchange would have ended gravely for them. Wiley told his daughter that he was pretty “tough in them days” and was prone to smack someone when provoked.3 Indeed, he was furious when he heard about the threats against his wife, mother-in-law, and small children.4 Wiley had purchased the house on Walrond Avenue around 1913 and was very proud of that accomplishment.5 The Kennedys had lived there for a few years before the mob attempted to force them out.

The senior Kennedy explained to his daughter that they were not prepared to leave the home they owned, so Wiley and Zella “set about to see what could be done to protect their right to stay in their house.” First Flo’s father visited the local police station on Twenty-Second and Flora. The officer listened to his account and then told him that his white neighbors could not legally evict them. “It was his home and he could do whatever was necessary to protect it,” the officer advised. Wiley took note of the fact that the police offered the family no protection beyond these words. Moreover, he doubted that the officers or the court would side with him against his white neighbors should the thugs return. Flo also surmised that the policeman’s words must have “been pretty cold comfort to Zella who was home at night alone so much of the time with only grandma and us.”6

Undaunted, the Kennedys sought legal counsel, but the attorney gave them similar advice. He cautioned that “there wasn’t much they could do to the neighbors” to stop their threats or to punish them for harassment but added “that there wasn’t much the neighbors could do to them, Legally, that is.”7 The lawyer and the police had no advice on how to prevent the men from delivering on their promise. In the spring and summer of 1919, black residents of Kansas City, like their counterparts in cities across the country, faced continuous abuse from whites intent on hardening the racial divide after World War I. Anxiety that his home would be the white terrorists’ next target no doubt gnawed at Wiley.

These worries were confirmed when a group of young white men continued the campaign of intimidation that the older men had started. They began “making a habit … of congregating next door in a little shack” behind the Kennedys’ home. One youth would openly have sexual relations with his lady friend there at all hours of the day and night. These young men were brazenly claiming the outside edge of the Kennedy property as their own and showing complete disregard for the family. Perhaps Wiley feared that the men would continue to encroach on his land and eventually lay claim not only to the family’s home but also to his wife, mother-in-law, and daughters. He repeatedly asked the white men to leave, but they ignored him and returned to the shed whenever they pleased. Finally, fed up with his family being disregarded and disrespected, Wiley waited until he saw one of the men bringing a woman around back. He walked over and asked the couple to take their business elsewhere. Irritated, the male trespasser puffed up his chest and flatly told Flo’s father that he was “lucky he was still there and he wasn’t taking any orders from any niggers.” As far as he was concerned, the land belonged to the whites and “they didn’t want any niggers in the neighborhood.” He warned the senior Kennedy that he “better get the hell over in his own yard while he still had one.” It would not be long “before somebody [would] come and chase him out of the neighborhood altogether.” The girl “giggled” at her boyfriend’s swift dismissal of Flo’s father.8

As the story goes, Wiley then pulled out a piece of broken scaffolding he had hidden close by and “whacked him across the head good a couple of times.” All hell broke loose. The white man “started hollerin’ and this girl was yelling” as Wiley continued to clobber him, holding him tightly so he could not escape. Finally, “I let him go and he ran like a turkey,” Flo’s father said triumphantly.9 The border of the Kennedy property would not be used as a white man’s latrine or bordello, and the family refused to be evicted from the home they owned. After that day, the white thugs stopped using the shed as their own and no one ever tried to evict them again. Wiley and Zella raised their five daughters in that house.

That white men were engaging in illicit sex so close to his home no doubt added to Wiley’s fear for the safety of his family. Black women and girls were especially vulnerable to sexual violence from white men who used rape and other forms of assault to hinder African Americans from exercising their citizenship rights and to debase and deny their humanity.10 These brutal acts were routinely ignored by law enforcement and went unpunished. As historian Hannah Rosen explains, “part of a larger performance of [white] power was resisting and disavowing the transformations brought about by emancipation” through the rape of black women.11

In the 1960s, when Kennedy was asked about her political background, she normally told the more dramatic and armed version of the story she had grown up hearing, perhaps from her older sister Evelyn, rather than the account she later obtained directly from her father. In the inflated version her father was armed with a gun when he challenged a group of white vigilantes who attempted to evict their family. The steps her parents took to secure the safety of their home and children by contacting the police and an attorney were omitted, and the story centered on her father’s unrelenting bravery.12 “Daddy was ready to shoot somebody and kill him to keep our house,” Flo explained to interviewers who were interested in her political roots.13

The story of her father’s armed defiance in the face of white terrorism was the narrative Flo frequently recounted to reporters, scholars, and audiences who wanted to know how she became a black feminist radical. “Did you grow up political?” they would ask. Most assumed that the Kennedy family was involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and belonged to a black church. But Kennedy’s response was always the same: “We were political in the sense that we never took any shit.”14 Kennedy wanted to make clear that her family’s political pedigree was not tied to any organization but to guts and gumption. Flo described her own personality as an extension of her father’s confrontational and rebellious persona.15 In her retelling of the family fable, Wiley was unrelenting, armed, and fearless when faced with injustice.

For Kennedy, her politics developed from her father’s defiance of oppression. This was the radical tradition from which she sprang and that she continued to pursue. Her father’s strong belief in personal autonomy and freedom contributed to her formation as a black feminist radical. The numerous family stories she heard and the confrontations she witnessed secured Wiley’s image in Flo’s memory. When Kennedy was active in the radical political movements of the 1960s and 1970s, she strengthened the image of herself as rebellious, fearless, and even outrageous. The Black Power movement’s provocative militancy, while often derided and attacked by government officials, the mainstream media, and some civil rights organizations, was celebrated by those who advocated assertive self-defense as the most effective means of securing respect and liberation. The story Flo offered at that time was deployed to inspire her audience of radical activists, especially white feminists, to attempt to mimic her daring.

Flo’s mother, Zella, exerted an equally important influence, even though she was absent from the version of the story Flo generally told. As an adult Flo spoke and wrote of her mother’s courage, resilience, and unconventional parenting.16 Zella showed Flo how to challenge the gendered limitations frequently placed on black girls and women in the 1920s and 1930s. She rejected middle-class moralizing and notions of female respectability that limited black women’s mobility, pleasure, and sexual expression. Flo’s experiences as the daughter of Zella and Wiley Kennedy contributed to her evolving politics and set the stage for the activism that would follow her move to New York City.

“That’s Why I Don’t Have the Right Attitude toward Authority”: Power, Family, and Wiley Kennedy

In 1909, Wiley Choice Kennedy moved to Kansas City to find a better job and to escape the racial bigotry of the Deep South. A decade earlier he had left Elm Bluff, Alabama, where his mother was once enslaved. Far less is known about Wiley’s father, other than he too was once enslaved. At the age of twenty, Wiley packed his belongings, left the Dallas County plantation, and traveled more than two hundred miles north to Huntsville.17 He departed for the city just as Alabama was attempting to reclaim its financial status as Cotton King.18 Before the Civil War, Alabama had been the country’s leading supplier of cotton, and politicians and business elites sought to regain that position by keeping newly freed black families tied to the land as sharecroppers. The most powerful weapon they used to punish those who attempted to leave and to intimidate the rest into staying was the lynch mob. In the 1890s Alabama led the country in the highest number of lynchings per year, while Dallas County had the highest number in the state.19 When Wiley moved from Elm Bluff, he was fleeing not only the economic limitations of sharecropping but also the threat of death faced by any and every black person who pushed back against the status quo.

Wiley quickly discovered that Huntsville was no promised land. Although he could read and write, he found few opportunities to earn a decent wage.20 African Americans in the South were routinely barred from the higher-paying jobs in cotton mills and other industries.21 Most black men picked up work as day laborers or farmhands when it was available.22 In Huntsville, Wiley toiled as a “lot boy,” tending horses and mules for a livestock dealer, until he saved enough money to move over six hundred miles farther north and west with his brother Wilson. He was part of the steady trickle of blacks who made their way to Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, during the two decades prior to the Great Migration.23

When Wiley arrived in Kansas City in 1909, he found a well-established community of more than 23,000 African Americans.24 Some of these families had been enslaved in rural Missouri and moved to St. Louis or Kansas City after emancipation, but most were “exodusters” who migrated from the former Confederacy to Kansas after the end of Reconstruction. Many Kansas City residents moved back and forth across the Missouri River, depending on opportunities for work and housing.25 A few years after he arrived, Wiley garnered a highly coveted job as a waiter and worked his way to headwaiter in the “biggest an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 | Political in the Sense That We Never Took Any Shit

- 2 | Similarities of the Societal Position of Women and Negroes

- 3 | All Men and Flo

- 4 | The Fight Is One That Must Be Continued

- 5 | Black Power May Be the Only Hope America Has

- 6 | Absorbed Her Wisdom and Her Wit

- 7 | I Was the Force of Them

- 8 | Not to Rely Completely on the Courts

- 9 | Form It! Call a Meeting!

- Epilogue | Until We Catch Up

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index