- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Forty thousand people died trying to cross international borders in the past decade, with the high-profile deaths along the shores of Europe only accounting for half of the grisly total.

Reece Jones argues that these deaths are not exceptional, but rather the result of state attempts to contain populations and control access to resources and opportunities. "We may live in an era of globalization," he writes, "but much of the world is increasingly focused on limiting the free movement of people."

In Violent Borders, Jones crosses the migrant trails of the world, documenting the billions of dollars spent on border security projects and their dire consequences for countless millions. While the poor are restricted by the lottery of birth to slum dwellings in the aftershocks of decolonization, the wealthy travel without constraint, exploiting pools of cheap labor and lax environmental regulations. With the growth of borders and resource enclosures, the deaths of migrants in search of a better life are intimately connected to climate change, environmental degradation, and the growth of global wealth inequality.

Reece Jones argues that these deaths are not exceptional, but rather the result of state attempts to contain populations and control access to resources and opportunities. "We may live in an era of globalization," he writes, "but much of the world is increasingly focused on limiting the free movement of people."

In Violent Borders, Jones crosses the migrant trails of the world, documenting the billions of dollars spent on border security projects and their dire consequences for countless millions. While the poor are restricted by the lottery of birth to slum dwellings in the aftershocks of decolonization, the wealthy travel without constraint, exploiting pools of cheap labor and lax environmental regulations. With the growth of borders and resource enclosures, the deaths of migrants in search of a better life are intimately connected to climate change, environmental degradation, and the growth of global wealth inequality.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Violent Borders by Reece Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Immigration Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The European Union:

The World’s Deadliest Border

The Spanish city of Melilla, a crescent of sandy beaches and modernist architecture nestled on the rocky Mediterranean coast, is a fortified garrison that has survived sieges and invasions since it was founded. The ancient city is mentioned in 2,000-year-old Roman geographical texts and was acquired by Spain in 1497, at the end of the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors. Over the ensuing centuries, Melilla was reinforced with city walls and troop deployments to protect it from multiple attempts to retake it. What sets Melilla apart from Seville, Granada, and other reconquered Spanish cities is that it is not on the Iberian Peninsula. Melilla and its sister city, Ceuta, are across the Strait of Gibraltar, the only outposts of Spain—and by extension the European Union—on the North African coast. As the only land borders between the European Union and African countries, both Melilla and Ceuta have become beacons for migrants attempting to set foot in the EU and apply for asylum.1 Today Melilla still resembles a fortified garrison, but now the walls, fences, and security personnel are in place as a bulwark against not military invasion but the movement of refugees and migrants.

I traveled to Melilla and Nador, a bustling port city of approximately 300,000 on the other side of the Moroccan border, in March 2015 to see the unfolding migration crisis firsthand. After visiting the fence complex and the old market, I settled into a chair at an open-air café, beside several fruit vendors with heaping piles of strawberries on carts, for a glass of sweet Moroccan mint tea. Isaac, a Ghanaian migrant, heard me speaking English with a colleague and approached to ask for some money. His wife, Gifty, stayed in the street with their newborn son Samuel strapped to her back, while their four-year-old son Prince, in torn ragged clothes, wandered back and forth between them.2 In 2012 the family had left Ghana, where they faced the options of working in low-wage subsistence agriculture or grinding out an existence in the slums of Accra. They had traveled through West Africa before arriving in Nador, expecting to spend a short time in the city before continuing their journey into Europe.

Nador, like many Moroccan cities, is vibrant and contradictory, with gleaming new sedans passing street vendors, hawkers, and farmers bringing their crops to market by oxcart. The city leaders have ambitions of making Nador a low-cost tourist destination and are constructing a long seafront promenade with benches under palm trees. On the outskirts of the urban core, beyond the future tourists’ gaze, new apartment blocks are going up haphazardly to house workers. Whether or not the European tourists eventually arrive, Nador is already a popular destination for migrants from across Africa and the Middle East who gather to slip through the EU checkpoint with false documents, climb over the fence in the early morning hours, or catch a boat headed for the Spanish mainland, tantalizingly close on the other side of the Mediterranean.

Refugees from Syria typically go through the checkpoint because their appearance matches the residents of Nador, who have identity cards that allow them to enter Melilla legally for the day. Migrants from West Africa, like Isaac and Gifty, gather in camps in the forests on Mount Gurugu, the peak that looms above Nador and Melilla, before attempting to jump the Spanish fences in large groups to ensure that at least a few make it through before border guards locate them and send them back to Morocco. Spain began to construct fences and barricades on the boundaries of Melilla in 1993, and they have been redesigned and expanded multiple times. The current wall complex is made up of three fences, the tallest of which is six meters (20 feet), all heavily reinforced to prevent them from being knocked down by a truck. The Spanish Guardia Civil, in older white trucks with green doors, patrol the roads along the edge of the fences, looking for anything out of place. If migrants make it over all three fences and set foot in the European Union, Spain is obligated to hear their asylum requests and provide them shelter. However, if they only make it over the first or second fence, they have not yet set foot in the EU and can be returned to Morocco. This is why there are often images in the news of dozens of migrants perched on the fences, with Guardia Civil waiting for them below. The migrants stuck on the fence have been stopped, but they are waiting to see if an opportunity to sneak past the guards might still present itself.

© José Palazón Osma 2016

The border fence in Melilla, Spain

In the past five years, as the number of migrants attempting to enter Melilla has continued to grow, Spain has contracted with Morocco to transfer much of the work of guarding the border to the Moroccan side. The European Union signed a joint immigration agreement with Morocco in 2013, which provides funding in exchange for help from the Moroccan authorities in preventing migrants from reaching the Melilla fence. While the Spanish fence is sometimes termed a “humanitarian fence” because it does not use barbed wire or razor wire, the new Moroccan fence, built with EU funds in 2015, is decidedly not: it consists of rolls of concertina wire wrapped with barbed wire, with sentry posts every hundred meters. In February 2015, a few weeks before my visit, the Moroccan authorities had carried out a major operation to locate and detain migrants in the areas surrounding Melilla. They cleared the major migrant camps on Mount Gurugu, detained hundreds of migrants, and burned their structures and supplies. They moved the migrants to detention facilities across Morocco, but predominantly in the south, far from the edges of the European Union. It was unclear whether Morocco would eventually release the migrants or deport them.

Isaac and Gifty had avoided the raids on the migrant camps by living by themselves. They had never attempted to jump the fence—it would have been too difficult with small children —and were instead looking to travel to Europe by boat. They had already made three attempts, but had been pushed back by the Moroccan coast guard before they even made it away from the coastline. Their infant was born while they were living in the forests on the hills above Nador. They spend their days wandering through the city looking for money and food, relying on the kindness of the local residents to help them get by while they wait for another opportunity to travel to Europe. Isaac sat and chatted with us for a while. He was articulate and friendly, but had a weary look in his eyes. When I asked him if he ever considered going back to Ghana, he said no. “We have been gone for three years. What would I say to my family if they saw me?” While we talked, their son Prince wandered off and came back a moment later with a proud smile and a large strawberry in his hand. A kind Moroccan fruit vender had given it to him.

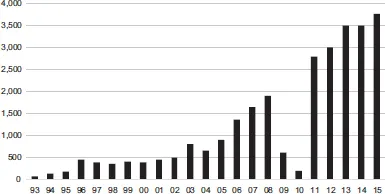

Although Isaac, Gifty, Prince, and Samuel remain stuck in the bleak existence of unwanted migrants in Morocco, at least they still have their lives. Many other migrants who do manage to find their way onto a boat are not as lucky. The International Organization for Migration reports that more than 23,700 migrants have died attempting to enter the EU since 2004.3 The death rate is increasing, with more than 3,500 deaths in 2014 and 3,770 in 2015.4 Globally, more than half the deaths at borders in the past decade occurred at the edges of the EU, making it by far the most dangerous border crossing in the world.

The European migration crisis

This was not supposed to be the story of borders in the EU in the era of globalization.5 Through the 1990s, the dominant media narrative was the removal of borders in Europe. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and in the early 1990s the Iron Curtain lifted as the Soviet Union collapsed. Former Soviet states became independent and many transitioned to democracy and open capitalist economies. In 1995, the Schengen Area, named for the small town in Luxembourg where the agreement was signed, was established, with visa-free movement through internal borders in Europe. By 2014, twenty-six countries were participating, including EU nonmembers Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. These changes in Europe seemed to symbolize the possibility that globalization might create a borderless world.

Migrant deaths at the edges of the European Union. Data from International Organization for Migration Missing Migrants Project (missingmigrants.iom.int) and Brian and Laczko, Fatal Journeys.

The reality is that EU borders were not removed in the 1990s, but simply moved to different locations. As internal border restrictions were loosened in the Schengen Area, more focus was placed on the external boundaries of the European Union at the Mediterranean and on its eastern edges.6 Individual countries continue to have primary responsibility for border enforcement, but a new agency, Frontex, was founded in 2005 to coordinate these border patrols and ensure security across the EU.7 New states wanting to join the Schengen Area must first demonstrate the security of their external borders, particularly at airports and in their visa requirements. The most significant change in the Mediterranean region over the past decade has been the militarization of border enforcement.8 Even within the European Union, the ideal of free internal movement is under threat. Denmark briefly instituted border controls in 2011; in 2015 many countries, including Austria, France, and Germany, reinstated border checkpoints on internal EU borders.

Most of the recent attention to the migration issue has focused on the war in Syria, but thousands of migrants died at the European Union’s borders years before that war even began: 1,650 people in 2007 and 1,900 in 2008. Despite the large numbers of deaths for over a decade, the issue only registered as a blip on the global agenda, in part due to the invisibility of bodies lost at sea. The 2013 tragedy at Lampedusa, a small Italian island that is the closest EU island to the coast of Africa, began to raise awareness. More than 500 migrants, mostly from Eritrea, Ghana, and Somalia, had boarded a smuggler’s small fishing boat and set out from the coast of Libya toward Europe.9 After two days at sea, on the third of October, when it was less than half a kilometer (a third of a mile) off the Lampedusa coastline, the boat encountered engine trouble. Most of the migrants could not swim. They could see lights on the island and tried to signal for help. At 6 A.M., someone on the boat set fire to a blanket in order to attract the attention of another ship, but the fire spread. All of the passengers moved to a safe section of the boat, but the weight on one side capsized it and sent them all into the cold Mediterranean. The people on the deck mostly survived, but those below, including many children, died. The final count of people who lost their lives in the shipwreck will never be known, but more than 350 died. Local fishers and the Italian coast guard rescued 155. In the funeral ceremony Italian authorities held on Lampedusa, the tiny coffins of the children each had a stuffed animal placed on top. Their parents’ coffins were each adorned with a single rose. The bodies that were not recovered lay in a watery grave. Only a few days later, another ship with migrants from Eritrea and Somalia sank in the same area, killing thirty-four people.

In August and September 2015, the violence of the borders of the EU burst onto the international news through a series of visually shocking stories. The first was the discovery of seventy-one bodies in an abandoned truck on the side of a highway in Austria. In contrast to bodies lost at sea, these migrants were already well within the boundaries of the EU and their deaths could not be ignored. This was followed by Hungary’s efforts to secure its border with Serbia to prevent migrants from passing through on their way to Germany. The Hungarian government built a razor-wire fence on its border, which resulted in images of women and children pushing their way through the dangerous fence. Then it closed the main train station in Budapest, stranding thousands of migrants, who slept on the platforms and in the lobby. After several days camped at the station, more than 10,000 people set off on a 500-kilometer (310-mile) march to reach Germany, which produced powerful images that evoked marches in the US South against segregation and in India against British colonialism. The most shocking image, however, was the photograph of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi’s dead body washed up on a Turkish beach. The innocent child lying facedown in the sand in bright red-and-blue clothing made it impossible to ignore the plight of refugees fleeing the war in Syria. Suddenly, the decade-long issue of deaths at the EU border became global news.

The year 2014, the latest year for which data are available, was characterized by the most people displaced by war in a single year since World War II (14 million) and the largest total displaced population in recorded history (59.5 million).10 All indications are that even more people were displaced in 2015. Many of the migrants arriving in Europe were leaving warravaged Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, but there were also large numbers of migrants from Ukraine, Eritrea, and West Africa. The civil war in Syria has raged since 2011 and the conflict crossed into Iraq in 2014 as the Islamic State consolidated its authority over a territory with more than 10 million inhabitants. From 2011 to 2015, 4 million Syrians fled the country. The war in Ukraine displaced 1.3 million people within the country and an additional 867,000 fled across its borders. Another large group of migrants come from Eritrea, where a 2015 UN investigation accused the government of President Isaias Afwerki of crimes against humanity, including torture, extrajudicial killings, forced labor, and sexual violence.11 The migration crisis in Europe in 2014 and 2015 was not singularly defined by people fleeing war. Like Isaac and Gifty, many migrants from West African countries such as Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal move primarily for economic reasons.

At the borders of the European Union—and the United States, for that matter—it is difficult to classify all of the people arriving under general categories like migrant, refugee, and asylum seeker. Refugee is a category created through the United Nations Convention on Refugees; it initially only applied to European refugees after World War II, but was revised in 1967 to remove the geographic and temporal limitations. The convention categorizes a refugee as someone who, “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”12

The category is a product of the state system of bounded territories because the primary action that a refugee has taken is crossing a border. The definition excludes most people who move, because poverty and environmental changes are not included. The poor, including Isaac and Gifty, are considered voluntary migrants.

Although there are problems with how the refugee system is organized, it does oblige receiving countries to provide basic care for the people who make claims and to consider their applications for refugee or asylum status. The European Union instituted a shared asylum policy in 2004 through the Dublin Regulations, which require applicants to request asylum in the first EU country they enter. Once a person makes the claim, their fingerprints are taken, and they are placed into a holding facility; provided food, shelter, and basic health care; and given a three-month temporary visa that allows them to move around while their claim is considered. There were 626,000 a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface to the Paperback Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The European Union: The World’s Deadliest Border

- Chapter 2: The US–Mexico Border: Rise of a Militarized Zone

- Chapter 3: The Global Border Regime

- Chapter 4: The Global Poor

- Chapter 5: Maps, Hedges, and Fences: Enclosing the Commons and Bounding the Seas

- Chapter 6: Bounding Wages, Goods, and Workers

- Chapter 7: Borders, Climate Change, and the Environment

- Conclusion: Movement as a Political Act

- Notes

- Index