- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Art-Architecture Complex

About this book

Hal Foster, author of the acclaimed Design and Crime, argues that a fusion of architecture and art is a defining feature of contemporary culture. He identifies a "global style" of architecture-as practiced by Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano-analogous to the international style of Le Corbusier, Gropius and Mies.

More than any art, today's global style conveys both the dreams and delusions of modernity. Foster demonstrates that a study of the "art-architecture complex" provides invaluable insight into broader social and economic trajectories in urgent need of analysis.

More than any art, today's global style conveys both the dreams and delusions of modernity. Foster demonstrates that a study of the "art-architecture complex" provides invaluable insight into broader social and economic trajectories in urgent need of analysis.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

GLOBAL STYLES

TWO

POP CIVICS

In 1971 one of the architectural surprises of the last century occurred: two young designers, neither French, won the most important commission in Paris since World War II, the design for the Centre Pompidou, and they became famous overnight. The two—a thirty-eight-year-old Englishman named Richard Rogers and a thirty-five-year-old Italian named Renzo Piano—designed an exuberant building that delighted some and outraged others: a glass box supported by a structure of steel and concrete, each façade a playful grid of prefabricated columns and diagonal braces, with a transparent escalator tube that snakes up the front, and other service tubes, picked out in primary colors, that run up the other sides. Imagined as a cross between the British Museum and Times Square updated for the information age, the Beaubourg was immediately popular (it still has more than 7 million visitors a year); plopped down in a broad piazza, it was also populist (Rogers calls it “a people’s center, a university of the street”).1 Yet the project was contradictory as well: a Pop building designed by two progressive architects for a bureaucratic state in honor of a conservative politician (the Gaullist Georges Pompidou), a cultural center pitched as “a catalyst for urban regeneration” (240) that assisted in the further erasure of Les Halles and the gradual gentrification of the Marais. Such tensions have run through the subsequent careers of both Rogers and Piano, who have long identified with the Left even as they have benefited from the patronage of the Center and the Right.2

Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1971–77. Photo © Renzo Piano Building Workshop.

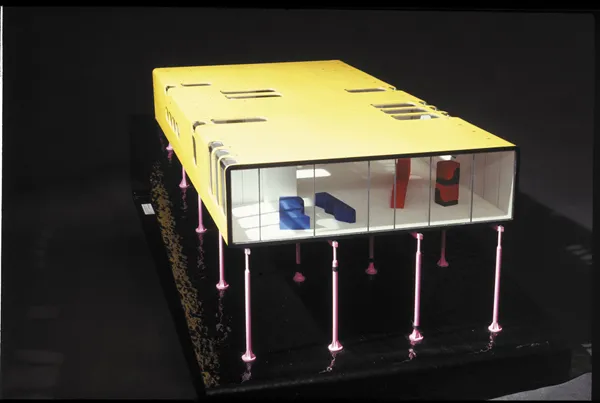

Although young by architectural standards in 1971, Rogers had several years of practice behind him. A graduate of the Architectural Association in London, he attended Yale in 1961–62 with Norman Foster, with whom he partnered, along with their spouses Su Brumwell and Wendy Cheeseman, until 1967. Difficult though it is to believe today, “Team 4” disbanded for lack of work, but not before they completed a breakthrough structure for Reliance Controls in Swindon (in southwest England), which the architectural writer Kenneth Powell describes as “neither a factory nor an office building nor a research station but a combination of all three” (20). The first of many “flexible sheds” that Rogers has designed over the years, the Reliance Controls Factory owed much to the elegant simplicity of the Case Study Houses in Southern California, especially the famous Eames House of 1949. Yet Rogers was also open to the new Pop and high-tech ideas of the 1960s. In 1968, for example, he conceived a mass-produced house made up of yellow panels zipped together and set atop legs that could be adjusted, and so positioned (in principle) almost anywhere. Displayed at the 1969 Ideal Home exhibition in London, the Zip-Up House was, in its high-tech optimism, one part Buckminster Fuller and, in its snappy material and speedy process, one part Archigram (this group had already proposed a sci-fi pod with robotic legs in 1963). However, unlike Fuller and Archigram, Rogers was willing to moderate his schemes in order to get them executed; in the same years, for instance, he built a home for his parents in Wimbledon that combined the Pop modularity of the Zip-Up House with the refined pragmatism of the Eames House. Yet even when large commissions appeared, Richard Rogers Partnership (RRP, now Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners) continued to experiment with modular designs in search of an economical architecture that was also inventive. Over the years, such schemes have included a mobile hospital for rural use, a diner conceived as an industrial product, an exhibition structure that is a giant system of shelves (a project presented by means of a Meccano model), and an apartment high-rise in which almost everything can emerge from a kit of prefabricated parts.

Given projects like the Reliance Control Factory and the Zip-Up House, the Beaubourg did not come out of the blue; nevertheless, as one of the few prominent Pop and high-tech buildings to see the light of day, it was received as a manifesto. First, it made clear the renewed importance of innovative engineering for contemporary architecture (Rogers and Piano were assisted by the great Irish engineer Peter Rice, who often consulted for RRP thereafter). Second, it offered one response to the open question of what postindustrial design might look like: “Most of us want it to look like something,” Reyner Banham once remarked in a discussion of Archigram; “we don’t want form to follow function into oblivion.”3 In this regard the Beaubourg was not as far-out as the “clip-on” and “plug-in” idiom of Archigram, with its “visually wild rich mess of piping and wiring and struts and cat-walks,” but Rogers and Piano did convey the unlikely mix of the communitarian and the consumerist that came to pervade much 1970s culture.4 Third, and more specific to Rogers, the Beaubourg demonstrated the advantage of mechanical services pushed to the outside of the structure—as a means not only to free up the interior space (at almost fifty meters deep, the open floors of the Beaubourg allow for diverse uses) but also to animate the building as a whole (there is an echo of Futurism here: one thinks of the power stations imagined by Antonio Sant’Elia, with whom Rogers was impressed as a student).5 In a way, the service tubes function as a contemporary form of ornament—they give the Beaubourg both detail and scale—and the movement of people across the piazza into the ground floor and up the escalator not only enlivens the center but connects it to the city as well. (The favored form of architectural imagery at RRP might well be “the mass ornament” of the occupants of its buildings—in circulation, in meetings, and so on.)6

Zip-Up House, 1968.

These are all idea-devices that recur in RRP designs. In effect Rogers presents a threefold motivation of advanced technology in the Beaubourg that continues in work to the present. In the first instance new technologies serve to engineer new kinds of open space, a priority that underscores his commitment to the innovations of modern architecture. Yet the trappings of these technologies are also put to use as ornament, which also speaks to his attention to the motivations of postmodern design. Finally, in the reconciliation of such demands RRP is able to speak to conflictual interests (again, communitarian and commercial, public and private)—a reconciliation that can also be read as a compromise.

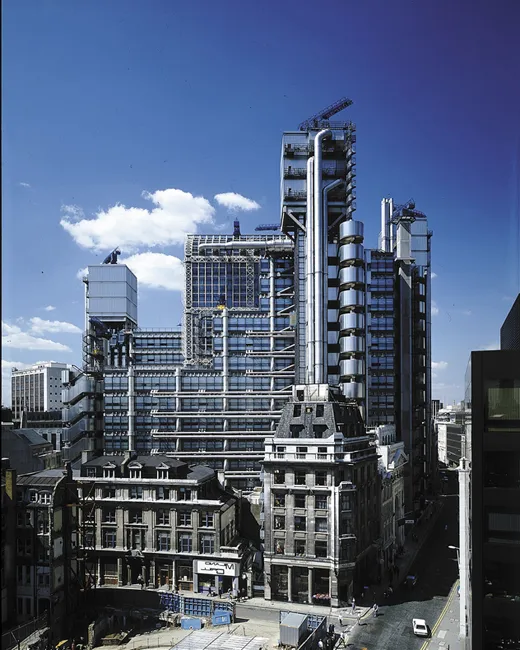

After the Beaubourg, Rogers parted with Piano (amicably, as he had done with Foster), and more projects came his way, some from the business establishment. In 1978 no less an institution than Lloyd’s of London selected Rogers to design its main building for insurance trading. The program called for a vast space, dubbed “The Room,” whose functions could expand and contract with trade volume, and Rogers responded with a full-height atrium surrounded by galleries connected by escalators and lifts. Here again services are moved to the exterior, with stairs located in corner towers—the first appearance of this signature feature of the practice. Along with the atrium arch, these stair towers lend a Gothic touch to the Pop look of Lloyd’s; at the same time the stainless-steel cladding connotes high-tech. Although Lloyd’s lacks the populist dimension of the Beaubourg, the fact that a building with Pop-Goth and high-tech attributes could appear at all in the conservative City was a surprise—a provocative one for some.

Lloyd’s established the language that RRP would go on to develop in different ways: an abundance of glazing, services on the outside when appropriate, with stairs and lifts often placed in towers, all done in such a way that interiors might be made as open, and exteriors as animated, as possible. The exteriors of its buildings do not express the interiors in a functionalist way; rather, the office strives to manifest the logic of its designs in a rationalist manner, often through an explicit hierarchy of elements. (Powell suggests that Louis Kahn, who thought in terms of “served” and “servant” spaces, influenced Rogers here, which again speaks to his modern affinities.) For example, RRP uses colors more often than most offices, yet it does so less for Pop effect than for design clarity: it applies its colors rigorously, and usually in order to articulate different services or sections. Although, as the Beaubourg showed early on, Rogers is responsive to the expectations of the capitalist world of mass culture, he also believes that architecture must offer a formal order that might mitigate the distractive clutter of that world.

Lloyd’s of London, 1978–86. Photo © Eamonn O’Mahony.

Lloyd’s was completed in 1986, at a time when conservative calls for the so-called contextualism of postmodern design were strong, and soon enough Rogers was drawn into the fray, sometimes with the Prince of Wales as an antagonist.7 Perhaps these skirmishes impeded further large-office commissions in the London area in the 1980s; in any case, they returned in the boom years of the 1990s and the 2000s. Among these buildings are Channel 4 Television Headquarters near Victoria Station (1990–94); 88 Wood St (1993–99) and Lloyd’s Register (1993–2000) in the City; Broadwick House in Soho (1996–2002); Waterside, the corporate headquarters of Marks & Spencer, in Paddington Basin (1999–2004); Chiswick Park, a business park in West London (1999–2010); and still other projects are in the works. Most of these buildings are cleanly designed and smartly engineered, and each has a flourish of its own—the bridge entrance and the concave front of Channel 4, for example, or the curved roof of Broadwick House. Yet these are more variations than innovations in the established RRP language: again, much glazing, cladding in steel or aluminum when necessary, exterior services and stair towers when possible, and color accents for articulation.

Channel 4 Television Headquarters, London, 1990–94. Photo © Richard Bryant / Arcaid.co.uk.

Patscentre, Princeton, 1982–85.

As might be expected, it was industry, both old and new, that really warmed to the rationality of RRP designs, and such projects also followed on the Beaubourg. In 1979 Rogers designed a center for Fleetguard in Quimper (western France); though a relatively heavy industry (it makes engine filters), Fleetguard received a rather light construction: a long box supported by slender columns that extend though the roof and are sta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- One: Image-Building

- Part I: Global Styles

- Part II: Architecture Vis-à-Vis Art

- Part III: Mediums After Minimalism

- Endnotes

- The Art-Architecture Complex Image Gallery

- Illustration Credits

- Index

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Art-Architecture Complex by Hal Foster in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Architecture Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.