- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

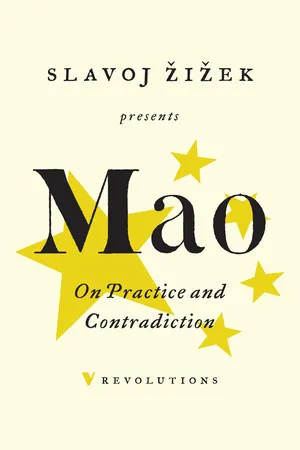

On Practice and Contradiction

About this book

These early philosophical writings underpinned the Chinese revolutions, and their clarion calls to insurrection remain some of the most stirring of all time. Drawing on a dizzying array of references from contemporary culture and politics, Zizek's firecracker commentary reaches unsettling conclusions about the place of Mao's thought in the revolutionary canon.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A SINGLE SPARK CAN

START A PRAIRIE FIRE

This was a letter written by Comrade Mao Zedong in criticism of certain pessimistic views then existing in the Party.

Some comrades in our Party still do not know how to appraise the current situation correctly and how to settle the attendant question of what action to take. Though they believe that a revolutionary high tide is inevitable, they do not believe it to be imminent. Therefore, they disapprove of the plan to take Kiangsi and only approve of roving guerrilla actions in the three areas on the borders of Fukien, Kwangtung and Kiangsi; at the same time, as they do not have a deep understanding of what it means to establish Red political power in the guerrilla areas, they do not have a deep understanding of the idea of accelerating the nation-wide revolutionary high tide through the consolidation and expansion of Red political power. They seem to think that, since the revolutionary high tide is still remote, it will be labour lost to attempt to establish political power by hard work. Instead, they want to extend our political influence through the easier method of roving guerrilla actions, and, once the masses throughout the country have been won over, or more or less won over, they want to launch a nation-wide armed insurrection which, with the participation of the Red Army, would become a great nation-wide revolution. Their theory that we must first win over the masses on a country-wide scale and in all regions and then establish political power does not accord with the actual state of the Chinese revolution. This theory derives mainly from the failure to understand clearly that China is a semi-colonial country for which many imperialist powers are contending. If one clearly understands this, one will understand first why the unusual phenomenon of prolonged and tangled warfare within the ruling classes is only to be found in China, why this warfare is steadily growing fiercer and spreading, and why there has never been a unified regime. Second, one will understand the gravity of the peasant problem and hence why rural uprisings have developed on the present country-wide scale. Third, one will understand the correctness of the slogan of workers’ and peasants’ democratic political power. Fourth, one will understand another unusual phenomenon, which is also absent outside China, and which follows from the first (that in China alone there is prolonged and tangled warfare within the ruling classes), namely, the existence and development of the Red Army and the guerrilla forces, and together with them, the existence and development of small Red areas encircled by the White regime. Fifth, one will understand that in semi-colonial China the establishment and expansion of the Red Army, the guerrilla forces and the Red areas is the highest form of peasant struggle under the leadership of the proletariat, the inevitable outcome of the growth of the semi-colonial peasant struggle, and undoubtedly the most important factor in accelerating the revolutionary high tide throughout the country. And sixth, one will also understand that the policy which merely calls for roving guerrilla actions cannot accomplish the task of accelerating this nation-wide revolutionary high tide, while the kind of policy adopted by Chu Teh and Mao Zedong and also by Fang Chih-min1 is undoubtedly correct – that is, the policy of establishing base areas; of systematically setting up political power; of deepening the agrarian revolution; of expanding the people’s armed forces by a comprehensive process of building up first the township Red Guards, then the district Red Guards, then the county Red Guards, then the local Red Army troops, all the way up to the regular Red Army troops; of spreading political power by advancing in a series of waves; etc., etc. Only thus is it possible to build the confidence of the revolutionary masses throughout the country, as the Soviet Union has built it throughout the world. Only thus is it possible to create tremendous difficulties for the reactionary ruling classes, shake their foundations and hasten their internal disintegration. Only thus is it really possible to create a Red Army which will become the chief weapon for the great revolution of the future. In short, only thus is it possible to hasten the revolutionary high tide.

Comrades who suffer from revolutionary impetuosity overestimate the subjective forces of the revolution2 and underestimate the forces of the counter-revolution. Such an appraisal stems mainly from subjectivism. In the end, it undoubtedly leads to putschism. On the other hand, underestimating the subjective forces of the revolution and overestimating the forces of the counter-revolution would also constitute an improper appraisal and be certain to produce bad results of another kind. Therefore, in judging the political situation in China it is necessary to understand the following:

1. Although the subjective forces of the revolution in China are now weak, so also are all organizations (organs of political power, armed forces, political parties, etc.) of the reactionary ruling classes, resting as they do on the backward and fragile social and economic structure of China. This helps to explain why revolution cannot break out at once in the countries of Western Europe where, although the subjective forces of revolution are now perhaps somewhat stronger than in China, the forces of the reactionary ruling classes are many times stronger. In China the revolution will undoubtedly move towards a high tide more rapidly, for although the subjective forces of the revolution at present are weak, the forces of the counter-revolution are relatively weak too.

2. The subjective forces of the revolution have indeed been greatly weakened since the defeat of the revolution in 1927. The remaining forces are very small and those comrades who judge by appearances alone naturally feel pessimistic. But if we judge by essentials, it is quite another story. Here we can apply the old Chinese saying, ‘A single spark can start a prairie fire’. In other words, our forces, although small at present, will grow very rapidly. In the conditions prevailing in China, their growth is not only possible but indeed inevitable, as the 30th May Movement and the Great Revolution which followed have fully proved. When we look at a thing, we must examine its essence and treat its appearance merely as an usher at the threshold, and once we cross the threshold, we must grasp the essence of the thing; this is the only reliable and scientific method of analysis.

3. Similarly, in appraising the counter-revolutionary forces, we must never look merely at their appearance, but should examine their essence. In the initial period of our independent regime in the Hunan-Kiangsi border area, some comrades genuinely believed the incorrect appraisal made by the Hunan Provincial Committee and regarded the class enemy as not worth a rap; the two descriptive terms, ‘terribly shaky’ and ‘extremely panicky’, which are standing jokes to this day, were used by the Hunan Provincial Committee at the time (from May to June 1928) in appraising the Hunan ruler Lu Ti-ping.3 Such an appraisal necessarily led to putschism in the political sphere. But during the four months from November of that year to February 1929 (before the war between Chiang Kai-shek and the Kwangsi warlords),4 when the enemy’s third ‘joint suppression expedition’5 was approaching the Chingkang Mountains, some comrades asked the question, ‘How long can we keep the Red Flag flying?’ As a matter of fact, the struggle in China between Britain, the United States and Japan had by then become quite open, and a state of tangled warfare between Chiang Kai-shek, the Kwangsi clique and Feng Yu-hsiang was taking shape; hence it was actually the time when the counter-revolutionary tide had begun to ebb and the revolutionary tide to rise again. Yet pessimistic ideas were to be found not only in the Red Army and local Party organizations; even the Central Committee was misled by appearances and adopted a pessimistic tone. Its February letter is evidence of the pessimistic analysis made in the Party at that time.

4. The objective situation today is still such that comrades who see only the superficial appearance and not the essence of what is before them are liable to be misled. In particular, when our comrades working in the Red Army are defeated in battle or encircled or pursued by strong enemy forces, they often unwittingly generalize and exaggerate their momentary, specific and limited situation, as though the situation in China and the world as a whole gave no cause for optimism and the prospects of victory for the revolution were remote. The reason they seize on the appearance and brush aside the essence in their observation of things is that they have not made a scientific analysis of the essence of the overall situation. The question whether there will soon be a revolutionary high tide in China can be decided only by making a detailed examination to ascertain whether the contradictions leading to a revolutionary high tide are really developing. Since contradictions are developing in the world between the imperialist countries, between the imperialist countries and their colonies, and between the imperialists and the proletariat in their own countries, there is an intensified need for the imperialists to contend for the domination of China. While the imperialist contention over China becomes more intense, both the contradiction between imperialism and the whole Chinese nation and the contradictions among the imperialists themselves develop simultaneously on Chinese soil, thereby creating the tangled warfare which is expanding and intensifying daily and giving rise to the continuous development of the contradictions among the different cliques of China’s reactionary rulers. In the wake of the contradictions among the reactionary ruling cliques – the tangled warfare among the warlords – comes heavier taxation, which steadily sharpens the contradiction between the broad masses of taxpayers and the reactionary rulers. In the wake of the contradiction between imperialism and China’s national industry comes the failure of the Chinese industrialists to obtain concessions from the imperialists, which sharpens the contradiction between the Chinese bourgeoisie and the Chinese working class, with the Chinese capitalists trying to find a way out by frantically exploiting the workers and with the workers resisting. In the wake of imperialist commercial aggression, Chinese merchant-capitalist extortions, heavier government taxation, etc., comes the deepening of the contradiction between the landlord class and the peasantry, that is, exploitation through rent and usury is aggravated and the hatred of the peasants for the landlords grows. Because of the pressure of foreign goods, the exhaustion of the purchasing power of the worker and peasant masses, and the increase in government taxation, more and more dealers in Chinese-made goods and independent producers are being driven into bankruptcy. Because the reactionary government, though short of provisions and funds, endlessly expands its armies and thus constantly extends the warfare, the masses of soldiers are in a constant state of privation. Because of the growth in government taxation, the rise in rent and interest demanded by the landlords and the daily spread of the disasters of war, there are famine and banditry everywhere and the peasant masses and the urban poor are close to starvation. Because the schools have no money, many students fear that their education may be interrupted; because production is backward, many graduates have no hope of employment. Once we understand all these contradictions, we shall see in what a desperate situation, in what a chaotic state, China finds herself. We shall also see that the high tide of revolution against the imperialists, the warlords and the landlords is inevitable, and will come very soon. All China is littered with dry faggots which will soon be aflame. The saying ‘A single spark can start a prairie fire’ is an apt description of how the current situation will develop. We need only look at the strikes by the workers, the uprisings by the peasants, the mutinies of soldiers and the strikes of students which are developing in many places to see that it cannot be long before a ‘spark’ kindles ‘a prairie fire’.

The gist of the above was already contained in the letter from the Front Committee to the Central Committee on 5 April 1929, which reads in part:

The Central Committee’s letter [dated 9 February 1929] makes too pessimistic an appraisal of the objective situation and our subjective forces. The Kuomintang’s three ‘suppression’ campaigns against the Chingkang Mountains was the high water mark reached by the counter-revolutionary tide. But there it stopped, and since then the counter-revolutionary tide has gradually receded while the revolutionary tide has gradually risen. Although our Party’s fighting capacity and organizational strength have been weakened to the extent described by the Central Committee, they will be rapidly restored, and the passivity among comrades in the Party will quickly disappear as the counter-revolutionary tide gradually ebbs. The masses will certainly come over to us. The Kuomintang’s policy of massacre only serves to ‘drive the fish into deep waters’,6 as the saying goes, and reformism no longer has any mass appeal. It is certain that the masses will soon shed their illusions about the Kuomintang. In the emerging situation, no other party will be able to compete with the Communist Party in winning over the masses. The political line and the organizational line laid down by the Party’s Sixth National Congress7 are correct, i.e. the revolution at the present stage is democratic and not socialist, and the present task of the Party [here the words ‘in the big cities’ should have been added]8 is to win over the masses and not to stage immediate insurrections. Nevertheless the revolution will develop swiftly, and we should take a positive attitude in our propaganda and preparations for armed insurrections. In the present chaotic situation we can lead the masses only by positive slogans and a positive attitude. Only by taking such an attitude can the Party recover its fighting capacity … Proletarian leadership is the sole key to victory in the revolution. Building a proletarian foundation for the Party and setting up Party branches in industrial enterprises in key districts are important organizational tasks for the Party at present; but at the same time the major prerequisites for helping the struggle in the cities and hastening the rise of the revolutionary tide are specifically the development of the struggle in the countryside, the establishment of Red political power in small areas, and the creation and expansion of the Red Army. Therefore, it would be wrong to abandon the struggle in the cities, but in our opinion it would also be wrong for any of our Party members to fear the growth of peasant strength lest it should outstrip the workers’ strength and harm the revolution. For in the revolution in semi-colonial China, the peasant struggle must always fail if it does not have the leadership of the workers, but the revolution is never harmed if the peasant struggle outstrips the forces of the workers.

The letter also contained the following reply on the question of the Red Army’s operational tactics:

To preserve the Red Army and arouse the masses, the Central Committee asks us to divide our forces into very small units and disperse them over the countryside and to withdraw Chu Teh and Mao Zedong from the army, so concealing the major targets. This is an unrealistic view. In the winter of 1927–28, we did plan to disperse our forces over the countryside, with each company or battalion operating on its own and adopting guerrilla tactics in order to arouse the masses while trying not to present a target for the enemy; we have tried this out many times, but have failed every time. The reasons are: (1) most of the soldiers in the main force of the Red Army come from other areas and have a background different from that of the local Red Guards; (2) division into small units results in weak leadership and inability to cope with adverse circumstances, which easily leads to defeat; (3) the units are liable to be crushed by the enemy one by one; (4) the more adverse the circumstances, the greater the need for concentrating our forces and for the leaders to be resolute in struggle, because only thus can we have internal unity against the enemy. Only in favourable circumstances is it advisable to divide our forces for guerrilla operations, and it is only then that the leaders need not stay with the ranks all the time, as they must in adverse circumstances.

The weakness of this passage is that the reasons adduced against the division of forces were of a negative character, which was far from adequate. The positive reason for concentrating our forces is that only concentration will enable us to wipe out comparatively large enemy units and occupy towns. Only after we have wiped out comparatively large enemy units and occupied towns can we arouse the masses on a broad scale and set up political power extending over a number of adjoining counties. Only thus can we make a widespread impact (what we call ‘extending our political influence’) and contribute effectively to speeding the day of the revolutionary high tide. For instance, both the regime we set up in the Hunan-Kiangsi border area the year before last and the one we set up in western Fukien last year9 were the product of this policy of concentrating our troops. This is a general principle. But are there not times when our forces should be divided up? Yes, there are. The letter from the Front Committee to the Central Committee says of guerrilla tactics for the Red Army, including the division of forces within a short radius:

The tactics we have derived from the struggle of the past three years are indeed different from any other tactics, ancient or modern, Chinese or foreign. With our tactics, the masses can be aroused for struggle on an ever-broadening scale, and no enemy, however powerful, can cope with us. Ours are guerrilla tactics. They consist mainly of the following points:

Divide our forces to arouse the masses, concentrate our forces to deal with the

enemy.

The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue.

To extend stable base areas,10 employ the policy of advancing in waves; when pursued by a powerful enemy, employ the policy of circling around. Arouse the largest numbers of the masses in the shortest possible time and by the best possible methods.

These tactics are just like casting a net; at any moment we should be able to cast it or draw it in. We cast it wide to win over the masses and draw it in to deal with the enemy. Such are the tactics we have used for the past three years.

Here, ‘to cast the net wide’ means to divide our forces within a short radius. For example, when we first captured the county town of Yunghsin in the Hunan-Kiangsi border area, we divided the forces of the 29th and 31st Regiments within the boundaries of Yunghsin County. Again, when we captured Yunghsin for the third time, we once more divided our forces by dispatching the 28th Regiment to the border of Anfu County, the 29th to Lienhua, and the 31st to the border of Kian County. And, again, we divided our forces in the counties of southern Kiangsi last April and May, and in the counties of western Fukien last July. As to dividing our forces over a wide radius, it is possible only on the two conditions that circumstances are comparatively favourable and the leading bodies fairly strong. For the purpose of dividing up our forces is to put us in a better position for winning over the masses, for deepening the agrarian revolution and establishing political power, and for expanding the Red Army and the local armed units. It is better not to divide our forces when this purpose ca...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Mao Zedong, the Marxist Lord of Misrule

- Note on Sources

- 1. A Single Spark can Start a Prairie Fire

- 2. Oppose Book Worship

- 3. On Practice: On the Relation between Knowledge and Practice, between Knowing and Doing

- 4. On Contradiction

- 5. Combat Liberalism

- 6. The Chinese People Cannot Be Cowed by the Atom Bomb

- 7. US Imperialism Is a Paper Tiger

- 8. Concerning Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR

- 9. Critique of Stalin’s Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR

- 10. On the Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People

- 11. Where Do Correct Ideas Come From?

- 12. Talk on Questions of Philosophy

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access On Practice and Contradiction by Mao Tse-Tung in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.